You're confused?

Thank goodness ... that means I'm in good company.

"A week is a long time in politics", and - for some UK politicians involved in the omnishambles of the current general election - it probably feels interminable.

It is also a long time in beekeeping.

Ten days ago I was searching in vain for mated queens in the rain, soaked to the skin, miserable and in a spectacularly bad mood.

I gave up and went home.

But last weekend the weather had improved, the sun was shining, there was a good nectar flow ... and I was soaked again (though this time with perspiration sweat). Even with my 'rock god' bandana on under my cap, there was sweat running down my face and fogging my glasses.

Not a pretty sight.

A bit of sun and some warm weather makes beekeeping easier and enjoyable.

Things are usually straightforward when there's a little rain (ideally overnight {{1}}) to keep the nectar flowing, moderate night temperatures, and warm and sunny days.

Colonies can get out and forage freely, and there's pollen and nectar available, so they expand in a relatively predictable and orderly fashion. Swarm preparations begin, but they're easy to spot early, as the benign conditions have made weekly inspections both possible and pleasurable.

Interesting times

But adverse conditions - prolonged periods of cold and/or wet weather - can delay colony expansion.

Though often by not as much as you would think.

You might not have had a chance to inspect the colonies, but the bees have been out foraging whenever they can. They 'know' {{2}} that if they didn't, they would miss the chance to reproduce (swarm) once the weather improves.

Changeable conditions - warm, cold, settled, unsettled, wet, dry - can make checking the hives problematic and, because of the variation in the rates at which colonies develop, perhaps more necessary.

But some of the most 'interesting' events occur when a prolonged cool/damp period rapidly segues to warm (or hot), dry and settled conditions.

It's like uncorking a shaken bottle of bubbly ... all that unrealised potential is suddenly released. Colonies rapidly transition from 'keeping busy, despite the conditions' to 'making hay, because of the conditions.'

Having seen the weather reports, this was exactly what I expected as I drove across to Fife.

I was not disappointed.

It was a busy couple of days of beekeeping; inspections, swarm control, making up nucs for queen mating, checking there were sufficient supers on the strongest colonies, marking queens ... all interspersed with a couple of situations I'd not experienced before {{3}}.

And, since I've written before about most of the 'housekeeping' beekeeping methods, I'll discuss these two events in a little more detail, together with some comments on handling queens.

Multiple queens in a swarm

I arrived at the apiary in late morning. The weather was perfect. The bees were busy ... surprisingly busy. There is usually a pronounced 'June gap' in my part of Fife once the oil seed rape (OSR) finishes. It's not unusual to have two to three weeks of tetchy bees, scratching about for relatively meagre resources, before the blackberry and lime start.

But not this year. The OSR had started early and then yielded for longer than expected. Despite the poor weather, the bees managed to fill a few supers during the drier or warmer (these terms are relative) periods. And now the OSR honey supers were off, there was another good nectar flow, with most frames dripping wet if not handled carefully.

On the first really warm inspection of the season {{4}} there were still a very few bright yellow bees returning to the hives, laden with what looked like OSR pollen (and there were a few plants still flowering in the field margins). However, most returning foragers were busy with something else and the entrances were a literal 'hive of activity'.

But one of the hives had a lot of bees clustered around the entrance, on the top of the hive stand and - when I assumed a grovelling position on my hands and knees to look at the open mesh floor (OMF) - underneath the hive.

Clearly this colony had swarmed, the clipped queen had spiralled unmajesterially to the ground, clambered up the leg of the hive stand and installed herself under the OMF.

I disassembled the hive, shook the bees from underneath the floor into a nuc box, and put the parental hive back together again.

I balanced the nuc box precariously on another (empty) nuc, and allowed the flying bees to settle and - hopefully - rejoin the queen. It was late afternoon and I still had to check on some queens at another site, so I left them to it and made a note to check and move the nuc the following morning.

Seek and ye shall find

But, the following morning the nuc box was empty 😔.

Clearly, I'd missed the queen, she'd remained somewhere under the OMF (perhaps hiding in the runner where the Varroa tray slides?) and the bees had returned there.

Except there were only a dozen or two bees under the OMF 🤔.

But there was a very large clump of bees on the ground about a metre away, around the leg of a nearby hive stand.

'Elementary, my dear Watson' ... my cack-handed fumbling with the floor had ejected the clipped queen onto the ground. By a minor miracle, I'd somehow failed to stomp repeatedly on her when flailing about sorting out the nuc, and the bees eventually - once I'd vacated the site and peace had returned - joined her.

So I got down on my hands and knees (again) and had a gentle little prod and poke through the clump of bees. The light was dodgy, and the swarm were intertwined with cuckoo grass and bindweed - a gardeners' nightmare.

Amazingly, I found the a queen.

Her left wing was clipped and she was unmarked. I was pretty sure she was the original from the box, but that the mark had worn off {{5}}.

I popped her in a cage and dangled it near the swarm, expecting them to obediently follow ... a sort of beekeeping Pied Piper.

They completely ignored her.

Harrumph.

I therefore placed the caged queen just inside the entrance to a nuc and left it adjacent to the swarm on the ground, before giving the bees a gentle puff or two of smoke to encourage them towards the invitingly dark - and now queenright - cavity.

And they're off

They didn't take the hint.

Instead, they took off.

Within a minute or so, the entire mass of bees took to the air in a fabulous whirling maelstrom, their wings glinting and flashing in the sunshine.

And they're off

I'm convinced that a swarm in flight is one of the greatest spectacles in beekeeping ... even if they're my bees and about to disappear over the apiary fence, never to be seen again.

But they didn't do that.

They milled around for a few minutes, never gaining more than a few metres of altitude, and slowly drifted across some scrubby ground to a small elder tree 15 metres away, where they settled at shoulder height.

The clipped queen was still in a cage in the nuc box.

There must have been a second queen {{6}} in the swarm, presumably a virgin.

After that, it was easy. I dropped the swarm into another nuc box, and left it under the tree to allow the flying bees to join the queen, before relocating it late in the afternoon.

With luck, the queen will be mated and laying by the time you read this.

I have a vague recollection of a study of queen numbers in swarms (Tarpy? Smith?), which showed that multiple queens are not unusual. I'll try and find it for a future post.

What I found interesting about this particular swarm was that the original clipped and laying queen (there were eggs in the hive) appeared to be unattractive to the swarm ... it was almost as though she was there as a bystander.

That reminded me that I've previously hived swarms containing clipped queens, only to find the clipped queen missing the following week ... does the swarm eject her, or was there also a virgin queen in the swarm that subsequently usurped her? If my notes were comprehensive enough, I might be able to work this out from timing of the appearance of eggs and larvae at the follow-up inspection {{7}}.

Multiple queens in a cell raiser

This is a controlled beekeeping interlude, between the more 'interesting' events of the weekend.

The monsoon the previous week had meant I'd abandoned half a dozen queens that had emerged - into cages - in a cell raiser {{8}}. I should have used them for requeening colonies and, by splitting the cell raiser into several boxes, for making up some new nucs for sale, overwintering (yes, it's not too soon to start thinking about this), or expansion.

The queens were fine. The cell raiser was broodless, and they'd filled many of the frames with nectar. However, importantly, they had not neglected the queens. Each cage was festooned with workers and the queens were clambering around inside, all looking great.

It was now time to do something with them.

Queens need a few days after emergence to mature sufficiently to go on orientation and mating flights. Since the weather in the intervening week had been poor, I'd effectively not 'lost' any time. They wouldn't have got mated in intermittent rain showers at 13°C (though the bees were clearly foraging under these conditions).

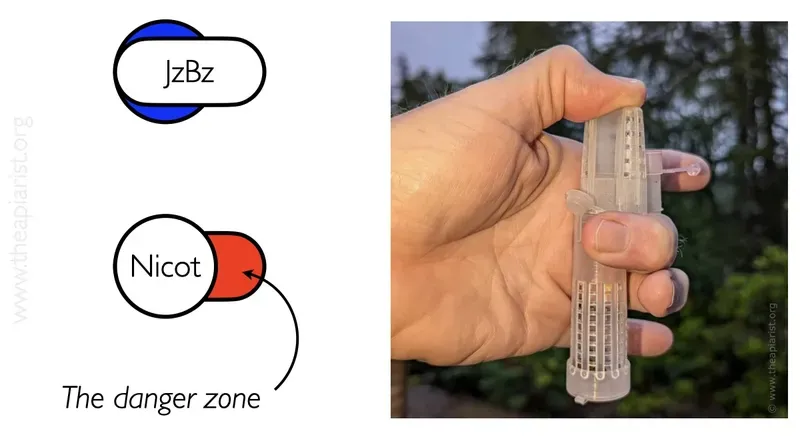

Nicot into JzBz will go

The queens were in Nicot cages. These taper (wide to narrow) from base to top. For queen introductions, I use JzBz cages, with the 'neck' plugged with fondant to delay release. These cages are oval in cross-section, and the 'neck' is too narrow and/or smooth for the queen to willingly march into the JzBz cage (been there, tried that, got the T-shirt).

How do you safely transfer the virgin from the Nicot cage to the JzBz introduction cage? {{9}}

I'm not keen on handling virgin queens if I can possibly help it:

- they're skittish and difficult to grab {{10}},

- it's usually something done in warm weather, so my gloved fingers will be coated with sticky propolis. Yes, I could take my glove off to improve dexterity {{11}} but I'd then struggle to put the nitrile glove back on my sweaty hand.

- I'd prefer the queen to smell of 'queen', rather than me. Acceptance rates of virgin queens are usually lower than of mated, laying queens, and I'm happy to use every advantage I can.

- virgins that are a week or so old can fly pretty well ... I write from bitter experience. 'Nuff said.

Queens tend to walk up, against gravity. Prepare the JzBz cage by plugging the 'neck' with a small blob of fondant or queen candy. Hold the Nicot and JzBz cages together, end-to-end. Although the openings of the cages are different shapes, the only space the queen can escape through is the region shown in red in the diagram below.

Cover that space with a finger, hold the cages with the JzBz on top, and the queen should march right up and in. A gentle shake can help, as can a puff of exhaled air (I think it's the CO2 she moves away from ... or halitosis).

Remove the Nicot cage, close and seal the JzBz cage and you're 'good to go'.

I split the cell raiser four ways, into 3 frame nucs, added a JzBz-caged queen to each, and - later that afternoon - moved most of them to another apiary to avoid losing flying bees back to the original hive location.

The weather has been reasonable this week, so I hope they're now all mated.

A drone laying queen, laying workers, or what?

On my last afternoon in Fife, I checked a vertical split that I'd set up - what felt like - weeks ago. At the previous check, there had been no mated (or visible) queen, and I was concerned that the colony would become drone layers.

My hive notes ominously said "last chance, use it or lose it".

The colony contained no worker brood, but did contain two or three patches of drone brood - in drone comb - together with a few randomly placed larvae (too young to sex) scattered around the comb.

That was a bit odd.

Drone laying queen (left) and laying workers (right)

If the queen was a drone layer (a DLQ), I'd have expected to see the classic bullet-shaped drone cells clustered in worker comb. DLQ's produce a standard laying pattern, typically in worker comb, but only lay unfertilised eggs.

Conversely, if the colony contained laying workers, I would not have expected to see clustered drone brood in drone comb. Laying workers can't - or don't - differentiate between worker and drone cells, but lay randomly.

However, it also made no sense for a queen to preferentially lay drone brood when there was no worker brood ... not a decision that would benefit the colony long-term.

Time was of the essence ... I had a 4 hour drive, a ferry to catch and a timed overnight closure on the A82 to beat (or enjoy a 60+ mile detour 😞).

I searched for the queen.

And failed to find her.

So, I moved the box a few metres away, reducing the numbers of flying bees around me, and searched - even more diligently - again.

There was no shortage of bees, but no sign of a queen.

Puzzling, but I'm certainly not infallible when it comes to finding queens when I need to {{12}}.

Drastic action

So I shook the bees out in front of the entrances of a row of queenright hives.

If the randomly placed larvae were laying workers, I would almost certainly have been shaking them out the following week anyway. Conversely, if the queen was a drone layer, then I needed to find and remove her before requeening. Since I suspected the former rather than the latter (or perhaps as well as), and had failed twice to find the queen, I decided the simplest course of action was to shake them out.

Despite disassembling the vertical split, lots of the flying bees accumulated on the roof and upper super of the original hive. This wasn't altogether unsurprising, but I was surprised at just how many bees had been in the box, and I wasn't keen to leave them clustered out in the open as afternoon turned to early evening {{13}}.

I had a spare virgin queen in a Nicot cage in my pocket. Out of curiosity, I placed this on the hive roof and the bees immediately started to cluster around it.

This appeared to be 'healthy interest' rather than aggression, so I transferred the queen to a JzBz cage, dangled it by the clustered bees and then - once a few dozen were clumped around the cage - hung it between the top bars of frames in a nuc box which I balanced on the hive roof {{14}}.

And, over the next 20 minutes or so, the bees just marched in.

... the bees just marched in

This was a Maisie's poly nuc with an integral floor. The nuc has small feet, resulting in a ~1 cm gap between the small landing board and whatever the nuc is standing on. These gaps confuse bees when they're marching towards the entrance ... they often cluster underneath the open mesh floor instead.

They can 'smell' the queen, but they are physically separated from her.

In the hope of reducing their confusion {{15}} I bridged the gap with a small cardboard box. Once the majority were ensconced in the nuc I moved it to a hive stand.

It will be interesting to see if there's a mated queen in the box next week 😄.

Or if there's another patch of drone brood 😠.

Having tidied up, I drove towards the evening sun, arriving at the West Coast as the cloud rolled in to produce a stunning light show over Eigg and Rhum.

And the moral of the story is ...

Actually, I'm not sure if there is one, but if there is, it's something like this:

- major changes in the weather may precipitate events in your colonies, so

- expect the unexpected, and

- even if it's confusing, try and understand and resolve the situation

- you might not be right - and I may well be wrong in my interpretations of the events described above - but I've had a 'best guess' and, even if nothing else, have made some reasonably comprehensive notes for the future.

- Spare queens are always useful.

Of course, not forgetting that it's not unusual to be confused by what the bees do, which is part of what makes beekeeping so challenging and enjoyable.

Email confusion

"He didn't call, he didn't write."

Most subscribers to The Apiarist read the emailed weekly newsletter and never visit the website.

But to receive the newsletter, you need to subscribe. ... and that needs a valid email address. And that email address is also needed if you want to sign in to the website, for example to temporarily suspend newsletters while on holiday, change your username, add comments, or to read posts only available to sponsors.

The email is needed because the site emails you a 'magic' link to verify your identity. No pesky passwords to forget.

And if you subscribed or sponsored The Apiarist using an email address containing errors, you will never receive any email from the site ... newbee@gmail.con will not work.

Read that email address again.

A simple typographical error, but one I see several times a week {{16}}.

I 'see' these because they bounce back from email servers with a 'username not known' or 'DNS fail' errors. I also get bounced email when the recipient's INBOX is full (a dozen or two a week).

I'm not worried about receiving these bounced emails ... they just disappear into an unmonitored account and are deleted.

I am worried that you might be trying to sign in to the website, or subscribe to the newsletter, and can't.

Catch-22

I've even had sponsors - signed up through Stripe - provide an invalid email. Not only will they never receive the Bees in the News newsletter (or the receipt for the payment), but they also cannot sign in to the site to correct the error, or read the posts.

And, if you sponsored The Apiarist but didn't receive a receipt or the newsletter, then look out for a postcard ... it's the only way I have to make contact.

Sponsorship

If you found this or other posts useful, informative or entertaining, then please consider becoming a sponsor of The Apiarist. It costs less than £1/week and ensures you receive every newsletter, including those - like Bees in the News #2 on the 5th, or the recent post on grafting for queen rearing - which are only available to sponsors.

Alternatively, you can rehydrate me and simultaneously fix my caffeine dependency ... and please spread the word to encourage others to subscribe.

Thank you

{{1}}: If you're going to dream, dream big.

{{2}}: Of course, they don't know ... it's all evolution and innate behaviour.

{{3}}: Or, more likely, not realised I'd experienced them before.

{{4}}: Why didn't I wear shorts under my beesuit? Rookie mistake.

{{5}}: After all, she could hardly have flown in from elsewhere.

{{6}}: At least one!

{{7}}: But that's a task for a dark winter evening ...

{{8}}: I describe the preparation of the cell raiser - a 12-frame double-decker nuc - in an earlier post.

{{9}}: I know you can buy a sort of 'netting muffler' to handle queens in the field, but it's one more thing to carry about (and lose).

{{10}}: Particularly with my normal level of "hands like feet" clumsiness.

{{11}}: Though it may be less easy to hold on to the queen without the help of the propolis 'glue'.

{{12}}: Actually, I'm the polar opposite ... the more I need to find her, the less chance I have of succeeding.

{{13}}: As an aside, whenever you shake a hive out, it helps the bees reorientate to new quarters if both the original hive - and the stand it was on - are moved, so removing any 'focus' for the evicted bees to gather around.

{{14}}: It's the Pied Piper trick again.

{{15}}: I'm a thoughtful beekeeper 😉.

{{16}}: Or some other variant, like newbe@gmail.com when the username is newbee, or newbee@gmale.com ... you get the idea.

Join the discussion ...