Women without men

The title of the post last week was The end is nigh which, looking at the fate of drones this week, was prophetic.

After the ‘June gap’ ended queens started laying again with gusto. However, there are differences in the pattern of egg laying when compared to the late spring and early summer.

Inspections in mid/late August {{1}} show clear signs of colonies making preparations for the winter ahead.

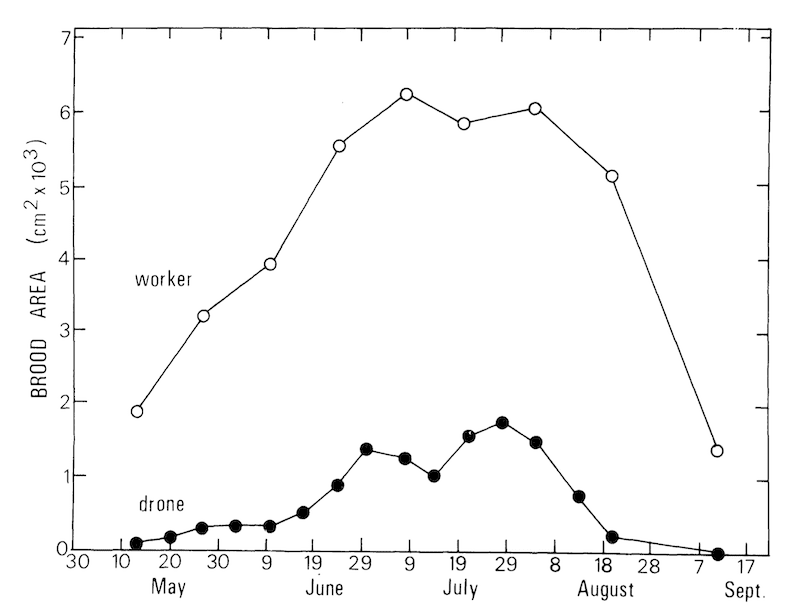

For at least a month the amount of drone brood in colonies has been reducing (though the proportions do not change dramatically). As drones emerge the cells are being back-filled with nectar.

The data in the graph above was collected over 50 years ago {{2}}. It remains equally valid today with the usual caveats about year-to-year variation, the influence of latitude and local climate.

Drones are valuable …

Drones are vital to the health of the colony.

Honey bees are polyandrous, meaning the queen mates with multiple males so increasing the genetic diversity of the resulting workers.

There are well documented associations between colony fitness and polyandry, including improvements in population growth, weight gain (foraging efficiency) and disease resistance.

The average number of drones mating with a queen is probably somewhere between 12 and 15 under real world conditions. However studies have shown that hyperpolyandry further enhances the benefits of polyandry. Instrumentally inseminated queens “mated” with 30 or 60 drones show greater numbers of brood per bee and reduced levels of Varroa infestation.

Why don’t queens always mate with 30-60 drones then?

Presumably this is a balance between access, predation and availability of drones. For example, more mating would likely necessitate a longer visit to a drone congregation area so increasing the chance of predation.

In addition, increasing the numbers of matings might necessitate increasing the number of drones available for mating {{3}}.

… and expensive

But there’s a cost to increasing the numbers of drones.

Colonies already invest a huge amount in drone rearing. If you consider that this investment is for colony reproduction it is possible to make comparisons with the investment made in workers for reproduction i.e. the swarm that represents the reproductive unit of the colony.

Comparison of the numbers of workers or drones alone is insufficient. As the graph above shows, workers clearly outnumber drones. Remember that drones are significantly bigger than workers. In addition, some workers are not part of the ‘reproductive unit’ (the swarm).

A better comparison is between the dry weight of workers in a swarm and the drones produced by a colony during the season.

It’s worth noting that these comparisons must be made on colonies that make as many drones as they want. Many beekeepers artificially reduce the drone population by only providing worker foundation or culling drone brood (which I will return to later).

In natural colonies the dry weight of workers and drones involved in colony reproduction is just about 1:1 {{4}}.

Smaller numbers of drones are produced, but they are individually larger, live a bit longer and need to be fed through this entire period. That is a big investment.

Your days are numbered

And it’s an investment that is no longer needed once the swarming season is over. All those extra mouths that need feeding are a drain on the colony.

Even though the majority of beekeepers see the occasional drone in an overwintering colony, the vast majority of drones are ejected from the hive in late summer or early autumn.

About now in Fife.

In the video above you can see two drones being harassed and evicted. One flies off, the second drops to the ground.

As do many others.

There’s a small, sad pile of dead and dying drones outside the hive entrance at this time of the season. All perfectly normal and not something to worry about {{5}}.

Drones are big, strong bees. These evictions are only possible because the workers have stopped feeding them and they are starved and consequently weakened.

A drone’s life … going out with a bang … or a whimper.

An expense that should be afforded

Some of the original data on colony sex ratios (and absolute numbers) comes from work conducted by Delia Allen in the early 1960’s.

Other colonies in these studies were treated to minimise the numbers of drones reared. Perhaps unexpectedly these colonies did not use the resources (pollen, nectar, bee bread, nurse bee time etc) to rear more worker bees.

In fact, drone-free or low-drone colonies produced more bees overall, a greater weight of bees overall and collected a bit more honey. This strongly suggests that colonies prevented from rearing drones are not able to operate at their maximum potential.

This has interesting implications for our understanding of how resources are divided between drone and worker brood production. It’s obviously not a single ‘pot’ divided according to the numbers of mouths to feed. Rather it suggests that there are independent ‘pots’ dedicated to drone or worker production.

Late season mating and preparations for winter

The summer honey is off and safely in buckets. Colonies are light and a bit lethargic. With little forage about (a bit of balsam and some fireweed perhaps) colonies now need some TLC to prepare them for the winter.

If there’s any reason to delay feeding it’s important that colonies are not allowed to starve. We had a week of bad weather in mid-August. One or two colonies became dangerously light and were given a kilogram of fondant to tide them over until the supers were off all colonies and feeding and treating could begin. I’ll deal with these important activities next week.

In the meantime there are still sufficient drones about to mate with late season queens. The artificial swarm from strong colony in the bee shed was left with a charged, sealed queen cell.

Going by the amount of pollen going in and the fanning workers at the entrance – see the slo-mo movie above – the queen is now mated and the colony will build up sufficiently to overwinter successfully.

Colophon

Men without Women

Men without women was the title of Ernest Hemingway’s second published collection of short stories. They are written in the characteristically pared back, slightly macho and bleak style that Hemingway was famous for.

Many of these stories have a rather unsatisfactory ending.

Not unlike the fate of many of the drones in our colonies.

Women without men is obviously a reworking of the Hemingway title which seemed appropriate considering the gender-balance of colonies going into the winter.

If I’d been restricted to writing using the title Men without Women I’d probably have discussed the wasps that plague our picnics and hives at this time of the year. These are largely males, indulging in an orgy of late-season carbohydrate bingeing.

It doesn’t do them any good … they perish and the hibernating overwintering mated queens single-handedly start a new colony the following spring.

{{1}}: At least here in Fife on the East coast of Scotland.

{{2}}: Not by me!

{{3}}: They are in excess, but increasing that excess might increase the numbers of matings.

{{4}}: Supporting a 1930 hypothesis by Fisher that natural selection should favour a 1:1 ration of “parental expenditure” in males and females over a population.

{{5}}: Unless you’re a drone perhaps.

Join the discussion ...