Winter losses

I lost 10% of my colonies this winter.

It’s always disappointing losing colonies, but it’s sometimes unavoidable.

I suspect the two I lost were unavoidable … though, as you’ll see, they weren’t completely lost.

April showers frosts

Late April may seem like mid-season for many beekeepers based in southern England. While they were adding their second super, the bees here in Scotland were only just starting to take their first few tentative flights of the year.

This April has been significantly cooler in Fife {{1}} than any year ‘since records began’.

However, the records I’m referring to are from the excellent Auchtermuchty weather report (gone, but not forgotten 😞) {{2}} which only date back to about 2013 … I like it because it’s local, not because it’s historically comprehensive 😉

The average April temperate has only been 5.5°C with 15 nights with frost in the first three weeks of the month. In contrast, the same month in 2019 and 2020 averaged over 9°C with only 3-4 nights with frosts {{3}}.

In both 2019 and 2020 swarming started at the end of April. Several colonies had queen cells when I first inspected them and I hived my first swarm (not lost from one of my colonies 😉 ) on the last day of the month.

First inspections and winter losses

Unsurprisingly, with appreciably lower temperatures, things are less well advanced this season. None of the colonies I inspected on the 19th were making swarm preparations. Instead, most were 2-4 frames of brood down on the strength I’d expect them to have before they started thinking about swarming.

Nevertheless, most were busy on a lovely spring day … lots of pollen (mainly gorse and some late willow by the looks of things) being delivered by heavily-laden foragers, and fresh nectar in some of the brood frames.

The first inspection of the season is an opportunity to not only check on the strength and behaviour of the colony, but also to do some ‘housekeeping’. This includes:

- swapping out old, dark brood frames (now emptied of stores) and replacing them with new foundationless frames

- removing excess stores to make space for brood rearing

- removing the first sealed drone brood in the colony to help hold back Varroa replication

And, as the winter is now clearly over, it’s the time at which the overall number of winter losses can be finally assessed.

Winter losses

Winter losses generally occur for one of four reasons:

- disease – in particular caused by deformed wing virus (DWV) vectored by high levels of Varroa in the hive. DWV reduces the longevity of the diutinus winter bees, meaning the colony shrinks in size and falls below a threshold for viability. There are too few bees to thermoregulate the colony and too few bees to help the queen rear new larvae. The colony either freezes to death, dwindles to the size of an orange, or starves to death because the cluster cannot reach the stores {{4}}.

- queen failure – for a variety of reasons queens can fail. They stop laying altogether or they only lay drone brood. Whatever the reason, a queen that doesn’t lay means the colony is doomed.

- natural disasters – this is a bit of a catch-all category. It includes things like flooded apiaries, falling trees and stampeding livestock. Although these things might be avoidable – don’t site apiaries in flood risk areas, under trees or on grazing land – these lessons are often learnt the hard way {{5}}.

- unnatural disasters – these are avoidable and generally result from inexperienced, or bad {{6}} , beekeeping. I’d include providing insufficient stores for winter in this category, or leaving the queen excluder in place resulting in the isolation of the queen, or allowing the entrance to be blocked. These are the things that the beekeeper alone has control over.

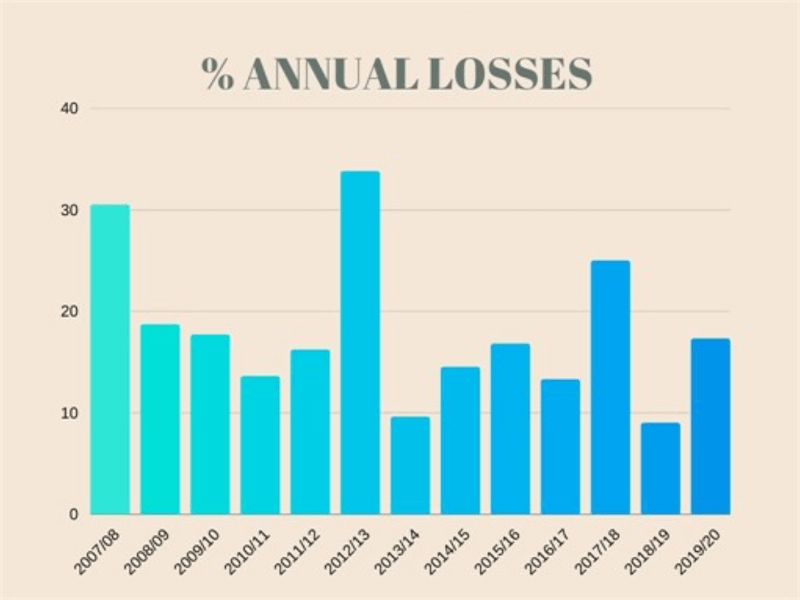

The BBKA run an annual survey of winter losses in the UK. This is usually published in midsummer, so the graph below is from 2020.

BBKA winter survival survey

Over the 13 years of the survey the average losses were 18.2% {{7}}. Long or particularly hard winters result in higher levels of losses.

Lies, damn lies and statistics

I’ve no idea how accurate these winter loss surveys are.

About 10% of the BBKA membership reported their losses, and the BBKA membership is probably a bit over 50% of UK beekeepers.

I would expect, with precious little evidence to back it up, that the BBKA generally represents the more ‘engaged’ beekeepers in the UK {{8}}. It also probably represents a significant proportion of new beekeepers who were encouraged to join while training.

So, like Amazon reviews, I treat the results of the survey with quite a bit of caution. I suspect beekeepers who have low losses complete it enthusiastically to ‘brag’ about their success (despite its anonymity), while those with large losses either keep quiet or are happy to share their grief.

Unlike Amazon reviews, I’d be surprised if there are many fake submissions to the BBKA and I’m not aware there’s a living to be made from selling fake colony survival reviews in bulk online.

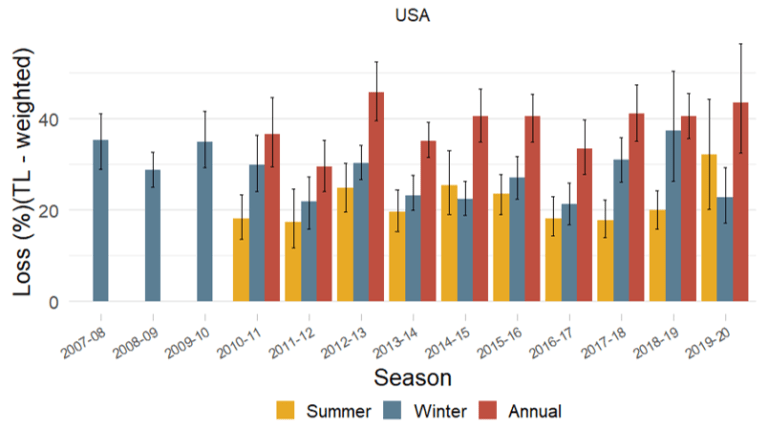

For comparison, the Bee Informed Partnership (gone, but not forgotten) in the USA runs a similar survey every year.

This survey covers about 10% of the colonies in the USA. Again it is voluntary and likely subject to the same inherent biases that may affect the BBKA survey.

The USA winter colony losses average ~28% over the same 13 year survey period.

Are US beekeepers less good at keeping their colonies alive than beekeepers in the UK?

Perhaps the US climate is less suited to honey bees?

Or, possibly, US beekeepers are simply more honest than their UK counterparts?

I doubt it {{9}}.

Running on empty

My two colony losses were due to queen failures.

In the first colony there was no evidence the queen had laid any brood since the previous autumn. There were about 6 seams of bees in the hive, but the outer 2-3 frames were solid with untouched winter stores.

This is usually a dead giveaway … literally. The colony hasn’t used the stores because they’ve not had any hungry mouths to feed. With no new brood the colony is doomed.

This queen appears to have simply run out of sperm and stopped laying. She was present (a 2019 marked queen and the same one I’d seen in August last year) and ambling around the frame, but she wasn’t even going through the pretence of inspecting cells before laying.

I removed the queen and united what remained of the colony over a nearby strong colony.

Assuming the queen stopped laying at the end of year all the bees in the hive – and there were a good number – were old, winter bees. These won’t survive long, but will provide a temporary boost to the colony I united them with.

Every little bit helps 🙂

Even more valuable than the bees were the frames they were on.

Most of the comb in the colony with the failed queen was relatively new. By uniting them I can quickly swap out the old comb (from the stronger hive #34) when I next inspect the hive. At the same time I’ll rescue the frames of sealed stores for use when making up nucs during queen rearing.

Drone laying queen

The second failure was a drone laying queen (DLQ).

These are usually unmistakeable … the brood is clustered, with drone pupae occupying worker brood cells. If the queen has been drone laying for some time there may be lots of undersized ‘runt’ drones present in the hive as well.

Again, this colony was doomed. With no new queens available and a lot of pretty old bees in the hive they could not be restored to a functioning colony.

However, many of the bees could be saved …

The colony wasn’t overrun with drones. Going by the amount of stores consumed it had probably been rearing worker brood since the winter solstice.

The queen was unmarked and unclipped. I strongly suspect she was a late-season supersedure queen who was very poorly mated.

The 3-4 weeks of drone brood rearing {{10}} had wrecked quite a few of the frames, but the bees were worth saving.

Under these circumstances I decided to shake the colony out.

When I do this I like to move the original hive and the stand it’s on. If you don’t move the stand the displaced bees tend to cluster near the original hive entrance, festooned from the hive stand.

In poor weather, or late in the afternoon, this can lead to lots of bees unnecessarily perishing.

However, the stand was shared with two other colonies, so couldn’t be removed. It was also late morning and the weather was excellent.

I moved the hive away and shook the bees out.

Sure enough … they returned to their original location.

They then marched along the hive stand to the entrance of the adjacent hive.

And, by the time I left the apiary in mid-afternoon there were only a few diehard bees clustered near where the original hive entrance was.

Why didn’t I just unite them as I’d done with the other failed queen?

Drone brood is a Varroa magnet

Varroa replicate when feeding on developing pupae. The longer development time of drone pupae (when compared with worker pupae) means that you get ~50% more Varroa from drone brood {{11}}.

Unsurprisingly perhaps (or not, because that’s the way evolution works) Varroa have therefore evolved to preferentially infest drone brood. When given the choice between a drone or worker pupa to infest, Varroa choose the drone about 10 times more frequently than the worker.

And that ~10:1 ‘preference ratio’ increases when drone brood is limiting … as it is early in the season.

What this means is that the first burst of drone brood production in a colony is very attractive to Varroa.

Unless there are compelling reasons to keep this very early drone brood – for example, a colony with stellar genetics I’d like to contribute as much as possible to the local gene pool – I often try and remove it.

If you use foundationless frames this is often as easy as simply cutting out a single panel of drone brood.

But, in the case of this drone laying queen, it meant that the logical action was to discard all of the drone brood to ensure I discarded the majority of the Varroa also present in the colony {{12}}.

Which is why I shook the colony out, rather than uniting them 🙂

Boxes of bees

Several colonies in one apiary went into the winter on double brood colonies. Inevitably, with the loss of bees during the winter months, the colony contracts and the queen almost invariably ends up laying in the upper box.

The first inspection of the season is often a good time to remove the lower box. It can be removed altogether, or replaced (above the other box) for a Bailey comb change if the weather is suitable.

At this stage of the year the lower box is often reasonably empty of bees and totally empty of brood.

If the comb in the lower box is old and dark (see the picture above) I place the upper box on the original floor and add an empty super on top. I then go through the lower box, shaking the bees into the empty super. Good frames are retained, the rest are destined for the wax extractor and firelighters.

Using an empty super helps ‘funnel’ the bees into the brood box.

Sometimes the queen has already laid up a frame or so in the lower box. Under these circumstances – particularly if the comb is relatively new – I’ll simply reverse the boxes, placing the lower box on top of the upper one. This results in the queen quite quickly moving up and laying up the space in the upper brood chamber.

It’s then time to add a queen excluder and the first super.

The beekeeping season has definitely started 🙂

Notes

I commented a fortnight ago about the apparent lateness of the 2021 spring. I’m adding this final note on the afternoon of the 23rd and have still yet to see or hear either cuckoo or chiffchaff on the west coast. Last year they were here in the middle of the month. This, combined with the temperature data (see above) show that everything is a week or two behind events last year.

Which means I can expect to start doing some sort of swarm prevention and control in the next fortnight.

{{1}}: Most of my colonies are still in Fife, even though I’m on the other side of the country … all of the discussion in this post is about bees in Fife.

{{2}}: Auchtermuchty – from the Gaelic Uachdar Mucadaidh, ‘upland of the pigs/boar’ – is a small town in Fife, situated on the southern slope of the North Fife Hills overlooking the flat, agriculturally-rich, Howe of Fife. Pronouncing Auchtermuchty correctly takes some practice, and most locals refer to it simply as ‘Muchty.

{{3}}: Of course, I’m writing this on the 21st/22nd and it might be tropical for the rest of the month, dragging the average temperature up to high single figures … some chance!

{{4}}: I don’t have time to discuss this here, but I strongly suspect that DWV and Varroa are the major cause of isolation starvation.

{{5}}: And often aren’t universal anyway – there are plenty of beautiful tree-shaded, riverside apiaries on grazing land which don’t ever suffer from these natural disasters.

{{6}}: A different thing altogether. Inexperience is excusable. We all have to learn, and learning from experience – although it can be painful – is important. Bad beekeeping is inexcusable. Why bother at all if you’re not going to look after your livestock in a way that maximises their chances of survival?

{{7}}: It’s not clear from the way the data is presented whether these losses occurred solely in the winter … let’s assume they are.

{{8}}: Though there are also quite a few experienced beekeepers who are not members – I’m one of them – for a variety of reasons including geography (I’m a member of the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association) or because they either don’t like joining things, or are opposed to the aims, goals, bureaucracy or organisation of the BBKA.

{{9}}: I’ll return to the BIP survey in the future. It’s better documented than the BBKA equivalent and has resulted in a number of peer-reviewed papers which make interesting reading (at least for us bee geeks … ). I’ll also include discussion of the similar COLOSS survey which covers ~35 countries.

{{10}}: Most remained in capped cells.

{{11}}: The actual numbers (averages across hundreds of pupae) are ~1.3 new Varroa for worker brood and ~2.2 for drone brood – see Know your Enemy for all the horribly incestuous details.

{{12}}: As an aside … DLQ’s often produce undersized ‘runt’ drones due to their being raised in bullet-shaped worker cells. I don’t know how well these drones perform as drones. Do they have the strength and stamina to catch and mate with queens in drone congregation areas?

Join the discussion ...