Winter covers and colony survival

A recent talk by Andrew Abrahams to the Scottish Native Honey Bee Society coincided with me catching up my {{1}} backlog of scientific papers on honey bees. I’d been reading a paper on the benefits of wrapping hives in the winter and Andrew commented that he did exactly that to fend off the worst of the wet weather. Andrew lives on the island of Colonsay about 75 km south of me and we both ‘benefit’ from the damp Atlantic climate.

The paper extolled the virtues of ‘covered’ hives and the data the researchers present looks, at first glance, compelling.

For example, <5% of covered hives perished overwinter in contrast to >27% of the uncovered control hives.

Wow!

Why doesn’t everyone wrap their hives?

However, a closer look at the paper raises a number of questions about what is actually benefitting (or killing) the colonies.

Nevertheless, the results are interesting. I think the paper poses rather more questions than it answers, but I do think the results show the benefits of hive insulation and these are worth discussing.

Bees don’t hibernate

Hibernation is a physiological state in which the metabolic processes of the body are significantly reduced. The animal becomes torpid, exhibiting a reduced heart rate, low body temperature and reduced breathing. Food reserves e.g. stored fat, are conserved and the animal waits out the winter until environmental conditions improve.

However, bees don’t hibernate.

If you lift the lift the roof from a hive on a cold midwinter day you’ll find the bees clustered tightly together. But, look closely and you’ll see that the bees are moving. Remove the crownboard and some bees will probably fly.

The cluster conserves warmth and there is a temperature gradient from the outside – termed the mantle – to the middle (the core).

If chilled below ~5.5°C a bee becomes semi-comatose {{2}} and unable to warm herself up again. The mantle temperature of the cluster never drops below ~8°C, but the core is maintained at 18-20°C when broodless or ~35°C if they are rearing brood. I’ve discussed the winter cluster in lots more detail a couple of years ago.

The metabolic activity of the clustered winter bees is ‘powered’ by their consumption of the stores they laid down in the autumn. It seems logical to assume that it will take more energy (i.e. stores) to maintain a particular cluster temperature if the ambient temperature is lower.

Therefore, logic would also suggest that the greater the insulation properties of the hive – for a particular difference in ambient to cluster temperature – the less stores would be consumed.

Since winter starvation is bad for bees (!) it makes sense to be thinking about this now, before the temperatures plummet in the winter.

Cedar and poly hives

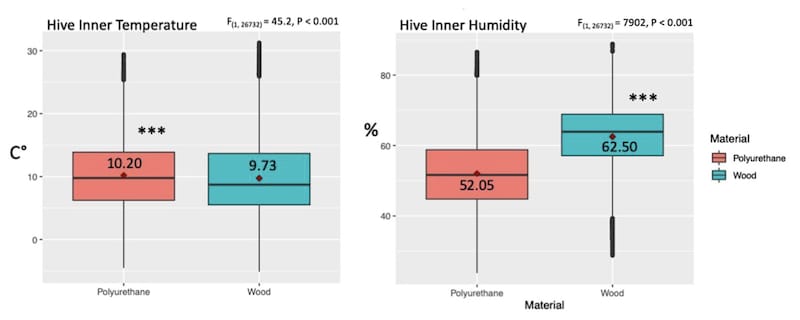

I’m not aware of many comparative studies of the insulation properties of hives made from the two most frequently used materials – wood and polystyrene. However, Alburaki and Corona (2021) have investigated this and shown a small (but statistically significant) difference in the inner temperature of poly Langstroth hives when compared to wooden ones.

Poly hives were ~0.5°C warmer and, perhaps more importantly, exhibited much less variation in temperature over a 24 hour period.

In addition to the slight temperature difference, the humidity within the wooden hives was significantly higher than that of poly.

The hives used in this study were occupied by bees and the temperature and humidity were recorded from sensors placed in a modified frame in the ‘centre of the brood box’. The external ambient temperature averaged 0°C, but fluctuated over a wide range (-10°C to 20°C) during the four month study {{3}}.

Temperature anomalies

Whilst I’m not surprised that the poly hives were marginally warmer, I was surprised how low the internal hive temperatures were. The authors don’t comment on whether the ‘central’ frame was covered with bees, or whether the bees were rearing brood.

The longitudinal temperature traces (not reproduced here – check the paper) don’t help much either as they drop in mid-February when I would expect brood rearing to be really gearing up … Illogical, Captain.

The authors avoid any discussion on why the average internal temperature was at least 5-8°C cooler than the expected temperature of the core of a clustered broodless colony, and ~25°C cooler than a clustered colony that was rearing brood.

My guess is that the frame with the sensors was outside the cluster. For example, perhaps it was in the lower brood box {{4}} with the bees clustered in the upper box?

We’ll never know, but let’s just accept that poly hives – big surprise 😉 – are better insulated. Therefore the bees should need to use less stores to maintain a particular internal temperature.

And, although Alburaki and Corona (2021) didn’t measure this, it did form part of a recent study by Ashley St. Clair and colleagues from the University of Illinois (St. Clair et al., 2022).

Hive covers reduce food consumption and colony mortality

This section heading repeats the two key points in the title of this second paper.

I’ll first outline what was done and describe these headline claims in more detail. After that I’ll discuss the experiments in a bit more detail and some caveats I have of the methodology and the claims.

I’ll also make clear what the authors mean by a ‘hive cover’.

The study was conducted in central Illinois and involved 43 hives in 8 apiaries. Hives were randomly assigned to ‘covered’ or ‘uncovered’ i.e. control – groups (both were present in every apiary) and the study lasted from mid-November to the end of the following March.

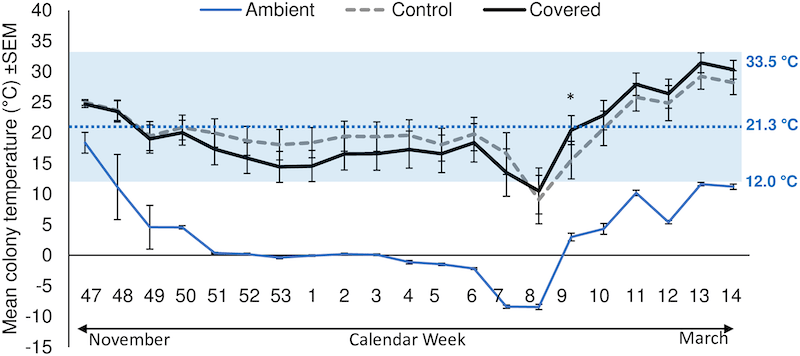

There were no significant differences in internal hive temperature between the two groups and – notably – the temperatures were much higher (15°-34°C) than those recorded by Alburaki and Corona (2021).

All colonies, whether covered or uncovered, got lighter through the winter, but the uncovered colonies lost significantly more weight once brood rearing started February. The authors supplemented all colonies with sugar cakes in February and the control colonies used ~15% more of these additional stores before the study concluded.

I don’t think any of these results are particularly surprising – colonies with additional insulation get lighter more slowly and need less supplemental feeding.

The surprising result was colony survival.

Less than 5% (1/22) of the covered hives perished during the winter but over 27% (6/21) of the control hives didn’t make it through to the following spring.

(Un)acceptable losses

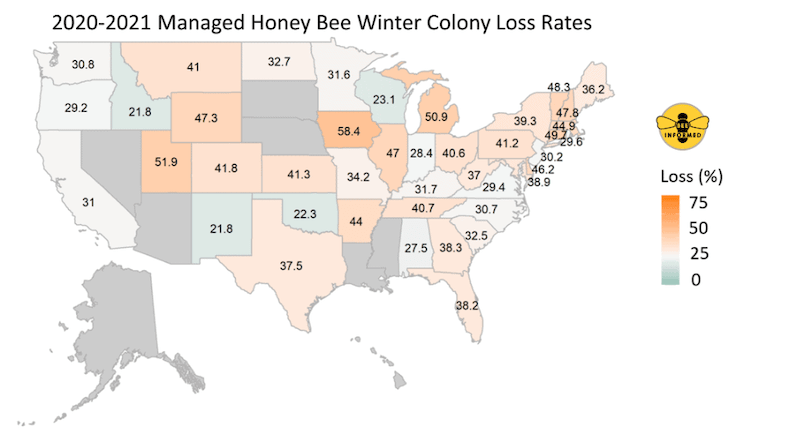

To put these last figures into context the authors quote a BeeI Informed Partnership (defunct 😞) survey where respondents gave a figure of 23.3% as being ’acceptable’ for winter colony losses.

That seems a depressingly high figure to me.

However, look – and weep – at the percentage losses across the USA in the ’20/’21 winter from that same survey {{5}}.

This was a sizeable survey involving over 3,300 beekeepers managing 192,000 colonies (~7% of the total hives in the USA).

If hive covers reduce losses to just 5% why does Illinois report winter losses of 47%? {{6}}

Are the losses in this manuscript suspiciously low?

Or, does nobody use hive covers?

I don’t know the answers to these questions, but I also wasn’t sure when I started reading the paper what the authors meant by a hive ‘cover’ … which is what I’ll discuss next.

Hive covers

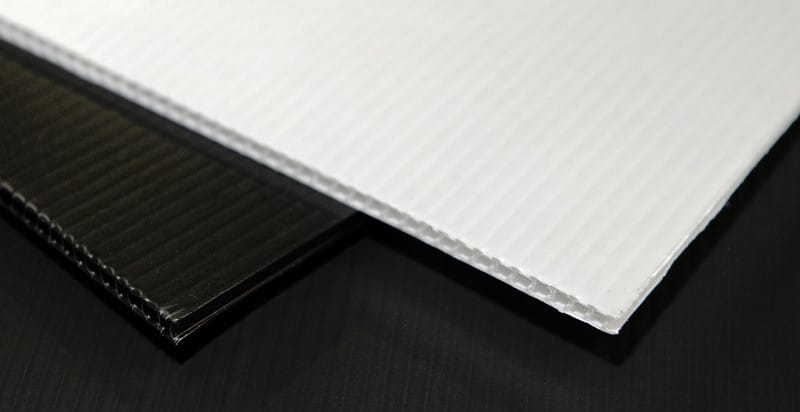

The hives used in this study were wooden Langstroths and the hive covers were 4 mm black corrugated polypropylene sleeves.

This is what I call Correx … one of my favourite materials for beekeeping DIY.

These hive covers are available commercially in the USA (and may be here, I’ve not looked). At $33 each (Yikes) they’re not cheap, but how much is a colony worth?

Significantly more than $33.

I’ve not bothered to make the conversion of Langstroth Deep dimensions (always quoted in inches 🙁 ) to metric and then compared the area of Correx to the current sheet price of ~£13 … but I suspect there are savings to be made by the interested DIYer {{7}}.

However, knowing (and loving) Correx, what strikes me is that it seems unlikely to provide much insulation. At only 4 mm thick and enclosing an even thinner air gap, it’s not the first thing I’d think of to reduce heat loss {{8}}.

Thermal resistance is the (or a) measure of the insulating properties of materials. It’s measured in the instantly forgettable units of square metre kelvin per watt m2.K/W.

I couldn’t find a figure for 4 mm Correx, but I did manage to find some numbers for air.

A 5 mm air gap – greater than separates the inner and outer walls of a 4 mm Correx hive cover – has a thermal resistance of 0.11 m2.K/W.

Kingspan

It’s not possible to directly compare this with anything meaningful, but there is data available for larger ‘thicknesses’ of air, and other forms of insulation.

An air gap of 100 mm has a thermal resistance of about 0.17 m2.K/W. For comparison, the same thickness of Kingspan (blown phenolic foam wall insulation, available from almost any building site skip) has a thermal resistance of 5, almost 30 times greater.

And, it turns out, St. Clair and colleagues also added a foam insulation board on top of the hive crownboard (or ‘inner cover’ as they call it in the USA). This board was 3.8 cm thick and has somewhat lower thermal resistance than the Kingspan I discussed above.

It might provide less insulation than Kingspan, but it’s a whole lot better than Correx.

This additional insulation is only briefly mentioned in the Materials and Methods and barely gets another mention in the paper.

A pity, as I suspect it’s very important.

I’m very familiar with Kingspan insulation for hives. All my colonies have a 5 cm thick block present all year – either placed over the crownboard, built into the crownboard or integrated into the hive roof.

Two variables … and woodpeckers

Unfortunately, St. Clair and colleagues didn’t compare the weight loss and survival of hives ‘covered’ by either wrapping them in Correx or having an insulated roof.

It’s therefore not possible to determine which of these two forms of protection is most beneficial for the hive.

For reasons described above I think the Correx sleeve is unlikely to provide much direct thermal insulation.

However, that doesn’t mean it’s not beneficial.

At the start of this post I explained that Andrew Abrahams wraps his hives for the winter. He appears to use something like black DPM (damp proof membrane).

Andrew uses it to keep the rain off the hives … I’ve used exactly the same stuff to prevent woodpecker damage to hives during the winter.

It’s only green woodpeckers (Picus viridis) that damage hives. It’s a learned activity; not all green woodpeckers appear to know that beehives are full of protein-rich goodies in the depths of winter. If they can’t grip on the side of the hive they can’t chisel their way in.

When I lived in the Midlands the hives always needed winter woodpecker protection, but the Fife Yaffles {{9}} don’t appear to attack hives.

Here on the west coast, and on Colonsay, there are no green woodpeckers … and I know nothing about the hive-eating woodpeckers of Illinois.

So, let’s forget the woodpeckers and return to other benefits that might arise from wrapping the hive in some form of black sheeting during the winter.

Solar gain and tar paper

Solar gain is the increase in thermal energy (or temperature as people other than physicists with freakishly large foreheads call it) of something – like a bee hive – as it absorbs solar radiation.

On sunny days a black DPM-wrapped hive (or one sleeved in a $33 Correx/Coroplast hive ‘cover’) will benefit from solar gain. The black surface will warm up and some of that heat should transfer to the hive.

And – in the USA at least – there’s a long history of wrapping hives for the winter. If you do an internet search for ‘winterizing hives’ or something similar {{10}} you’ll find loads of descriptions (and videos) on what this involves.

Rather than use DPM, many of these descriptions use ‘tar paper’ … which, here in the UK, we’d call roofing felt {{11}}.

Roofing felt – at least the stuff I have left over from re-roofing sheds – is pretty beastly stuff to work with. However, perhaps importantly, it has a rough matt finish, so is likely to provide significantly more solar gain than a covering of shiny black DPM.

I haven’t wrapped hives in winter since I moved back to Scotland in 2015. However, the comments by Andrew – who shares the similarly warm and damp Atlantic coastal environment – this recent paper and some reading on solar gain are making me wonder whether I should.

Fortunately, I never throw anything away, so should still have the DPM 😉

Winter losses

Illinois has a temperate climate and the ambient temperature during the study was at or below 0°C for about 11 weeks. However, these sorts of temperatures are readily tolerated by overwintering colonies. It seems unlikely that colonies that perished were killed by the cold.

So what did kill them?

Unfortunately there’s no information on this in the paper by St. Clair and colleagues.

Perhaps the authors are saving this for later … ’slicing and dicing’ the results into MPU’s (minimal publishable units) to eke out the maximum number of papers from their funding {{12}}, but I doubt it.

I suspect they either didn’t check, checked but couldn’t determine the cause, or – most likely – determined the cause(s) but that there was no consistent pattern so making it an inconclusive story.

But … it was probably Varroa and mite-transmitted Deformed wing virus (DWV).

It usually is.

Varroa

There were some oddities in their preparation of the colonies and late-season Varroa treatment.

Prior to ‘winterizing’ colonies they treated them with Apivar (early August) and then equalised the strength of the colonies. This involves shuffling brood frames to ensure all the colonies in the study were of broadly the same strength (remember, strong colonies overwinter better).

A follow-up Varroa check in mid-October showed that mite levels were still at 3.5% (i.e. 10.5 phoretic mites/300 bees) and so all colonies were treated with vaporised oxalic acid (OA).

In early November, mite levels were down to a more acceptable 0.7%. Colonies received a second OA treatment in early January.

For whatever reason, the Apivar treatment appears to have been ineffective.

When colonies are treated for 6-10 weeks with Apivar (e.g. early August to mid-October) mite levels should be reduced by >90%.

Mite infestation levels of 3.5% suggest to me that the Apivar treatment did not work very well. That being the case, the winter bees being reared through August, September and early October would have been exposed to high mite levels, and so acquired high levels of DWV.

OA treatment in mid-October would kill these remaining mites … but the damage had already been done to the ’diutinus’ winter bees.

That’s my guess anyway.

An informed guess, but a guess nevertheless, based upon the data in the paper and my understanding of winter bee production, DWV and rational Varroa management.

In support of this conclusion it’s notable that colonies died from about week 8, suggesting they were running out of winter bees due to their reduced longevity.

If I’m right …

It raises the interesting question of why the losses were predominantly (6 vs 1) of the control colonies?

Unfortunately the authors only provide average mite numbers per apiary, and each apiary contained a mix of covered and control hives. However, based upon the error bars on the graph (Supporting Information Fig S1 [PDF] if you’re following this) I’m assuming there wasn’t a marked difference between covered and control hives.

I’ve run out of informed guesses … I don’t know the answer to the question. There’s insufficient data in the paper.

Let’s briefly revisit hive temperatures

Unusually, I’m going to present the same hive temperature graph shown above to save you scrolling back up the page {{13}}.

There was no overall significant difference in hive temperature between the control and covered colonies. However, after the coldest weeks of the winter (7 and 8 i.e. the end of February), hive temperatures started to rise and the covered colonies were consistently marginally warmer. By this time in the season the colonies should be rearing increasing amounts of brood.

I’ve not presented the hive weight changes. These diverged most significantly from week 8. The control colonies used more stores to maintain a similar (actually – as stated above – marginally lower) temperature. As the authors state:

… covered colonies appeared to be able to maintain normal thermoregulatory temperatures, while consuming significantly less stored food, suggesting that hive covers may reduce the energetic cost of nest thermoregulation.

I should add that there was no difference in colony strength (of those that survived) between covered and control colonies; it’s not as though those marginally warmer temperatures from week 9 resulted in greater brood rearing.

Are lower hive temperatures ever beneficial in winter?

Yes.

Varroa management is much easier if colonies experience a broodless period in the winter.

A single oxalic acid treatment during this broodless period should kill 95% of mites – as all are phoretic – leaving the colony in a very good state for the coming season.

If you treat your colonies early enough to protect the winter bees there will inevitably be some residual mite replication in the late season brood, thereby necessitating the midwinter treatment as well.

I’m therefore a big fan of cold winters. The colony is more likely to be broodless at some point.

I was therefore reassured by the similarity in the temperatures of covered and control colonies from weeks 48 until the cold snap at the end of February. Covered hives should still experience a broodless period.

I’m off for a rummage in the back of the shed to find some rolls of DPM for the winter.

I don’t expect it will increase my winter survival rates (which are pretty good) and I’m not going to conduct a controlled experiment to see if it does.

If I can find the DPM I’ll wrap a few hives to protect them from the winter weather. With luck I should be able to rescue an additional frame or two of unused stores in the spring (I often can anyway). I stack this away safely and then use it when I’m making up nucs for queen mating.

I suspect that the insulation over the crownboard provides more benefit than the hive ‘wrap’. As stated before, all my colonies are insulated like this year round as I’m convinced it benefits the colony, reducing condensation over the cluster and keeping valuable warmth from escaping. However, wrapping the hive for solar gain and/or weather protection is also worth considering.

References

Alburaki, M. and Corona, M. (2022) ‘Polyurethane honey bee hives provide better winter insulation than wooden hives’, Journal of Apicultural Research, 61(2), pp. 190–196. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2021.1999578.

St. Clair, A.L., Beach, N.J. and Dolezal, A.G. (2022) ‘Honey bee hive covers reduce food consumption and colony mortality during overwintering’, PLOS ONE, 17(4), p. e0266219. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266219.

{{1}}: Enormous and never ending …

{{2}}: In the lab we place bees on an ice block to anaesthetise them before injection.

{{3}}: December to March.

{{4}}: These were double brood 10 frame Langstroths.

{{5}}: Note that these figures are preliminary – the peer-reviewed paper has yet to appear.

{{6}}: To say nothing of Michigan, Utah and Iowa.

{{7}}: Check this video out if you’re interested – the presenter reckons $8 for DIY.

{{8}}: It’s barely the last but one thing I’d think of.

{{9}}: The 18th Century country name for green woodpeckers, echoing the laughing cry of the bird. They’re also called rain-birds, a name that dates back to the mid-16th Century.

{{10}}: Note the Z not S.

{{11}}: Another example of ’two nations divided by a common language’.

{{12}}: Anyone doubting this happens should look at my CV. That’s a joke BTW.

{{13}}: Don’t say I never do anything for my readers …

Join the discussion ...