Where did it all go wrong?

Synopsis : Why was the summer 2023 honey crop so poor (at least here in Scotland) after a bumper Spring harvest, and what could or should I have done instead? Where did it all go wrong?

Introduction

Last weekend effectively marked the end of the worst summer season I’ve ever had since starting beekeeping.

At least when measured by honey yield.

Lots of other things went OK and some things went very well, but one of the reasons I keep bees is for honey production and that’s been an abject failure this summer.

I’ve yet to extract – and briefly considered leaving it all for the bees – but am pretty confident that it’s ~25 kg less than 2022.

That’s per hive 🙁 .

That’s a shortfall of over 200 kg from about the same number of production colonies.

I’ve ended up with just half a dozen supers, and not all of them are full.

I’m pretty certain I got more full supers in my very first year when I had just two hives … though this was helped by 30 acres of field beans just over the apiary fence.

Location, location, location 😉 .

So what went wrong?

How did this season differ from last season?

And, before I start, it’s not that 2023 was average and 2022 was freakishly good. Since returning to Scotland in 2015 the spring and summer honey crops have been reasonably consistent … and generally pretty good.

2022 was a little better than average and 2019 was appreciably worse, but all of them produced enough honey to make extracting (and the interminable cleaning up, jarring, labelling etc. afterwards) very worthwhile.

2023 is the outlier.

Why didn’t I leave the honey for the bees? Because I treat with Apivar and I’d prefer not to have to melt out the super frames that were exposed to miticide.

So, comparing this year with 2022 (and some earlier years), where did it all go wrong?

What hasn’t changed

One thing that hasn’t changed is the location, location, location.

The bees are in the same apiaries, spread across 10-15 miles of eastern Fife. All the apiaries were poor this summer, so I’m pretty certain it’s not a very localised change to the available forage.

My summer honey is what I’d describe as ‘mixed floral’ or ‘hedgerow’ honey. It’s a clear, runny honey which – in good years – has a distinctive zingy flavour from the lime. However, it’s anything but monofloral, and contains all sorts of stuff available in the environment.

What it probably isn’t – at least to any significant degree – is dependent on local agriculture. One farmer occasionally grows some field beans but they’re usually at the upper limit of foraging range. I’ve not seen any since 2020 or 2021.

The apiaries are situated in mixed farmland with lots of field margins, small copses, scrubby grazing and – in one instance – suburban gardens within range. The latter apiary tends to do a little better most years.

All the apiaries have access to oil seed rape early in the season. This gives the colonies a great boost and makes subsequent swarming relatively predictable.

The 2023 spring honey crop was outstanding.

Eventually 😉 .

Spring was late and it was only in the last couple of weeks of the OSR that it was warm enough for a real foraging bonanza. However, it all came good at the end and I finished with a record harvest which was taken off in the first week of June.

So, if the forage hasn’t changed then it must be the weather … right?

Local weather reports

My reference a couple of weeks ago to weather forecasting – and the subsequent helpful follow up comments from readers – was prompted by a need for accurate local predictions.

Local, because weather is local.

Here on the west coast the hills are low. Moisture-laden air bowling in from the Atlantic often blows over us, gets forced up by the bulk of Grampians, cools and then falls as rain.

Lots of it.

On the east coast, a few times a year, the haar drifts in off the North Sea. My coastal apiary can be a shivery 12°C when, just a few miles inland, it’s a balmy 20°C.

So, if local weather forecasts are needed, then a retrospective review of the impact of weather on honey yields needs local weather records. The gold standard are probably the HadUK datasets available for the UK under an Open Government Licence. They contain interpolated data on daily rainfall, temperatures, sunshine, humidity etc at a 1 km grid resolution {{1}}.

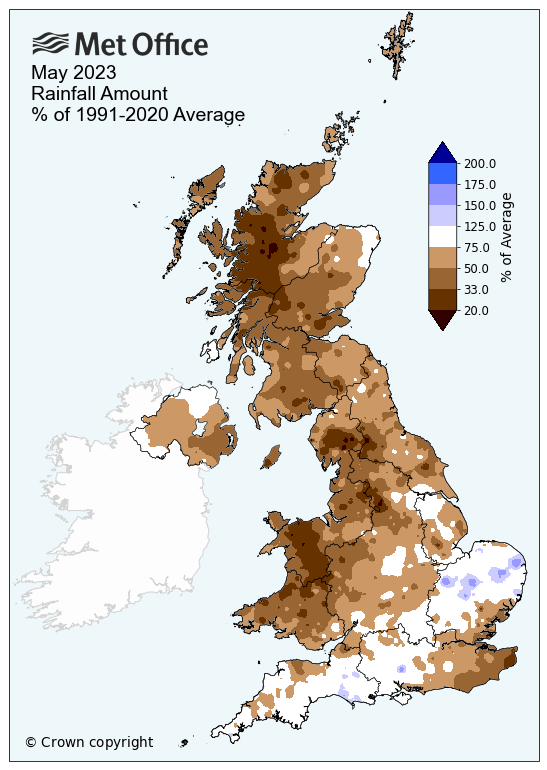

Regular readers will (although they might not realise it) be familiar with these datasets. These are the ones used to generate the Met Office UK actual and anomaly weather maps which regularly appear here. The map above shows May 2023’s rainfall anomaly; North Wales and the West coast of Scotland ‘enjoyed’ ~70% less rain than the 30 year average.

But there’s a problem with the HadUK datasets … they are not publicly available for the current year {{2}}.

Personal weather stations

But, all is not lost.

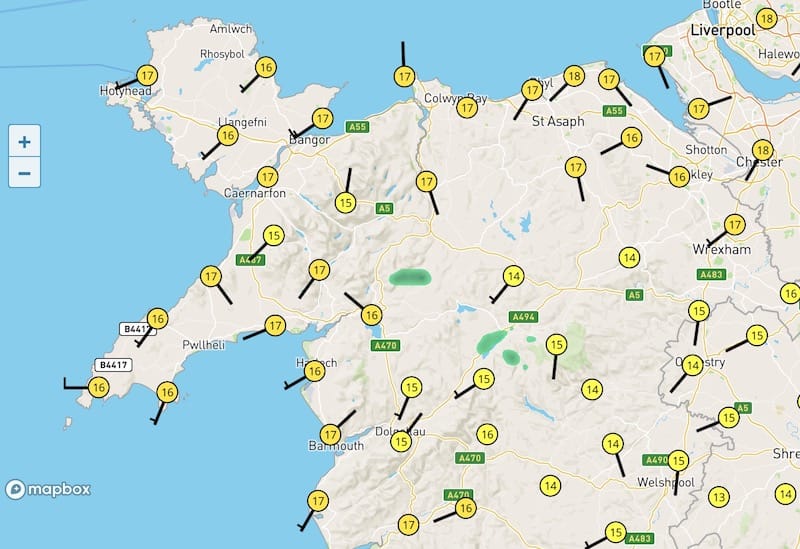

There are a rash {{3}} of personal weather stations in the gardens and on the roofs of weather enthusiasts, techie geeks, balloonists, surfers, kite flyers, gardeners … and beekeepers.

Some of these are isolated, stand-alone, units. They’re not much use to anyone but the owner/operator {{4}}.

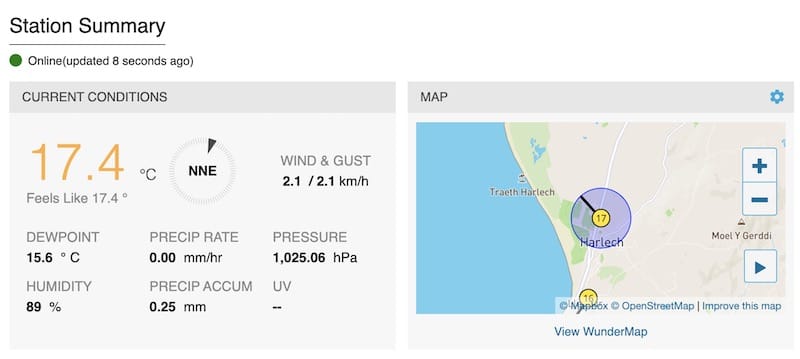

However, others share the data online, either directly via a web server or indirectly after uploading it to an internet weather service such as Wunderground or Windy.

From these you can get fancy graphical outputs for current or historical weather … or, by burrowing around a bit on the page, turgid tables of neatly aligned numbers that can be downloaded for analysis.

If you find one that’s local to your apiary do a little sanity-checking of the figures. Make sure the station is routinely online, that the data updates regularly and that the numbers seem logical (e.g. no -3°C in June). Unless the station is extremely well situated the windspeed and direction will be wrong {{5}}, but rainfall, temperature and potentially sunshine (radiation) should be reliable.

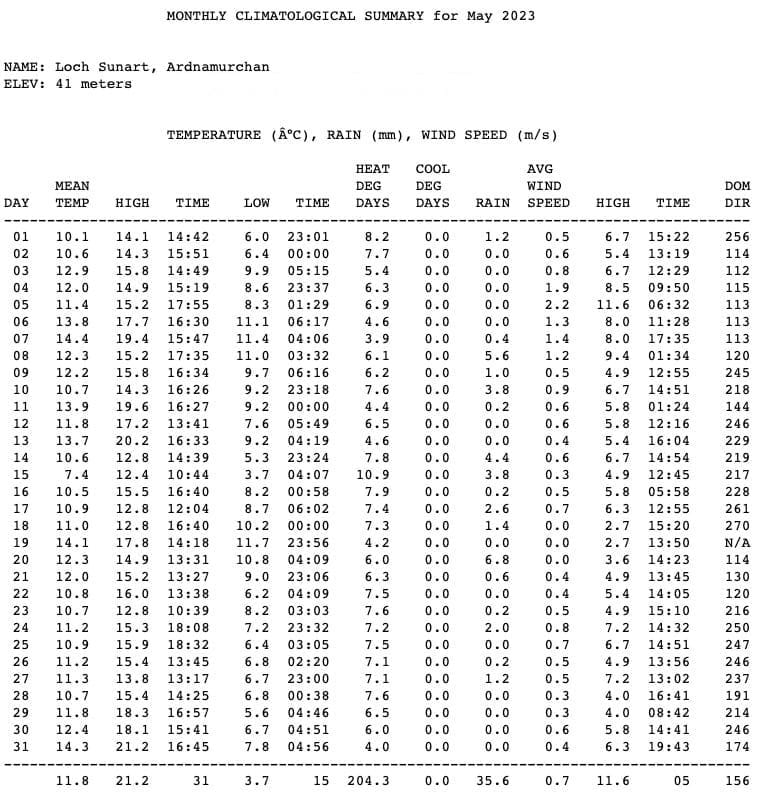

I have one of these weather stations on my shed for my ”Do queens really need calm, sunny days and temperatures over 20°C for mating?” project {{6}}. However, it’s 150 miles from my Fife apiaries, so hardly local.

Fortunately, in Fife there’s one in the next village that, with the exception of the summer of 2021, has been running for years and seems very dependable. All subsequent graphs are based on data from there.

Highs and lows

Comparison of the temperature maximum and minimum over the ~3.5 months from the start of May until the third week in August when the summer honey was taken off shows no major variation.

Temperature highs and lows in 2022 (blue) and 2023 (red) – click on this and subsequent graphs for larger versions.

The graph above shows the maximum (thick lines) and minimum (thin lines) temperatures in 2022 (blue) and 2023 (red). May and July are shaded so you can work out where you are in the season. I’ve used a similar layout for subsequent graphs.

It certainly doesn’t look as though 2023 was unseasonably cool or – perhaps with that week in mid-June {{7}} – particularly hot.

But just looking at the highs and lows could result in missing significant variation in the average daily temperatures … so I plotted that together with the rainfall over the same period.

Average temperatures and daily rainfall

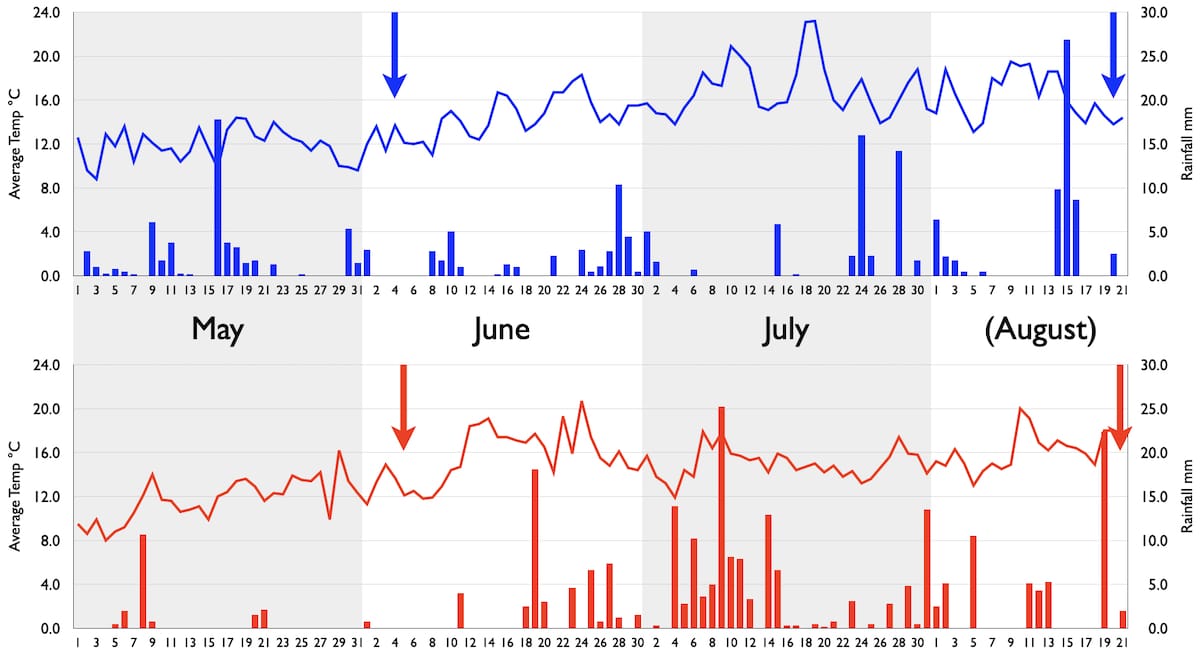

I’ve separated the 2022 and 2023 graphs this time to stop them getting too busy. Again the period displayed is the same. I’ve also marked – with arrows – the dates on which the spring and summer honey were taken off.

Remember, the spring harvest in 2023 was my best from Scotland, about 10% more than 2022 from slightly fewer colonies.

I don’t think there’s much to deduce from the temperatures (the line graphs). You can see the cool first week of May (which I was complaining about at the time), but it picked up by about the middle of the month. June was a bit warmer this year, but July was appreciably cooler than 2022.

However, the striking feature is probably not the temperature, it’s the rainfall (shown in the bar graph, plotted against the right hand vertical axis).

In 2023 there was almost no rain from about the 8th of May until the 19th of June. At the time I was more worried about the burn {{8}} that supplies our water drying up, but in retrospect this five week period will have had a profound effect on the moisture available in the soil for plant growth.

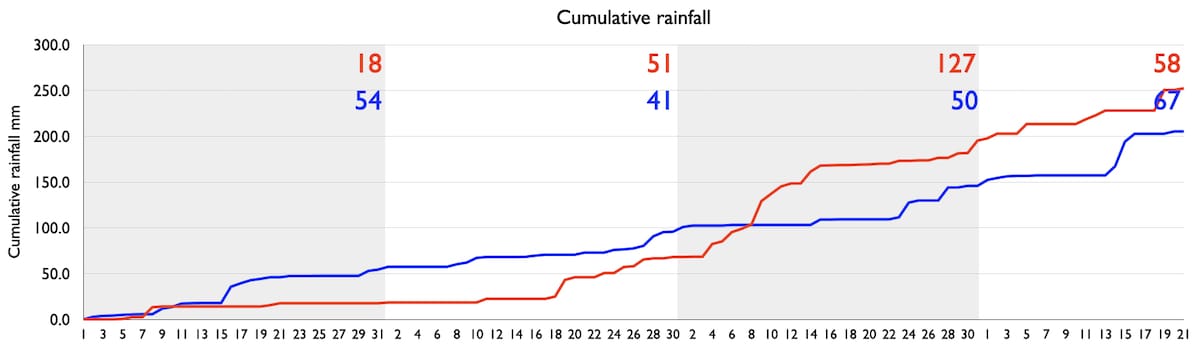

The difference between the two years is even more apparent in a graph of cumulative rainfall over the period. Although the final total is broadly similar (differing by only ~20%) 2023 essentially flatlines until mid-June and then rises much more steeply than 2022 until mid-July, from which point the slopes are similar.

Five weeks of drought in 2023 were followed by a month of wet weather, consequently also suppressing the average temperature.

More years, more data

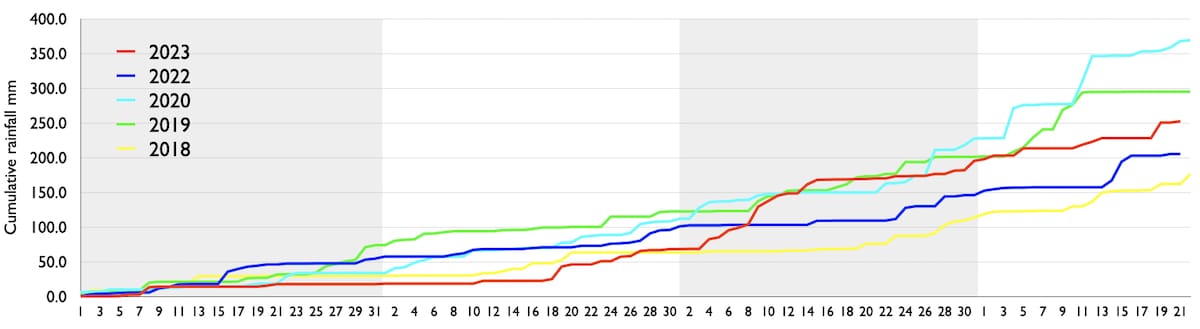

How do 2022 and 2023 compare with earlier years for which I have summer honey records?

Other than 2021 (where the weather station had a major hiccup) there are good datasets for every year since 2013.

I’ve plotted the last 5 years as that’s as far back as I can find the cumulative honey yields {{9}}. Of these, 2019 was poor, both for spring and summer honey.

Here’s the cumulative rainfall for each of those seasons (May to mid-August, as before).

Although it takes a little teasing apart, 2023 is clearly unusual in the protracted drought in late Spring/early summer. Even 2018 (yellow), the driest year overall, is only fractionally behind 2023 at the end of June (and finishes the period with 30% less rain by August).

The other thing that is striking is just how wet 2023 was from mid-June until mid-July. 150 mm of rain fell in the four weeks from 17/6/23. The red line rises more steeply over this period than any of the previous years, and at the end of this four week deluge is actually the wettest year of the five plotted.

However, rain alone isn’t necessarily a problem.

Most of the summer nectar flow probably occurs from mid-July until early/mid-August. During this period both 2019 (a poor year overall, but not catastrophic {{10}} ) and 2020 had more rainfall, and 2020 at least produced a lot of summer honey.

Not enough bees?

The majority of my colonies were requeened in 2023. Although the overall number of colonies are too small to draw any conclusions it was notable that the hive that produced the most honey {{11}} still has the queen from last year and showed no tendency to swarm.

Requeening colonies, using normal swarm control strategies, enforces a break in brood rearing.

I therefore checked back through my hive records to see if colonies had longer broodless periods in 2023 than 2022. All other things being equal e.g. prior strength or the subsequent laying rate of the new queen, a colony which experiences a longer brood break is likely to be weaker.

If the colony is short of workers during the main nectar flow it is likely to gather less honey.

Hive records

This is an even more approximate activity than looking at the weather records. My hive records are pretty good, but they are (obviously) only at weekly intervals. Furthermore, when I know a colony contains a new queen I tend not to rummage through the brood box unless really necessary (and if there’s a new queen in there it isn’t … so don’t 😉 ). Consequently, although I can identify broodless periods from my records, the precise duration (and therefore potential impact on colony strength) is, at best, vague.

However, if anything, queen mating was both more dependable and faster in 2023 than last year. Most queens were mated and laying by early/mid-June. I appreciate that it still takes ~6 weeks from the queen starting laying until her foragers are flying, but the speed with which queens were mated meant that worker numbers should not have become too depleted.

I’m going to spend a bit more time on this in the winter aided by coffee or red wine {{12}} to see if I’m missing something, but I currently think there were more than enough bees in the honey (non)production hives.

Nectar production and rainfall

I don’t have a definitive answer to the title of this post (Where did it all go wrong?) but it seems likely it’s due to one or more of the following reasons:

- protracted (~5 weeks) drought in late May and early/mid June. This didn’t apparently affect the nectar yields from the OSR, but could have had long-term consequences for the summer flowering forage.

- unusually wet weather from mid June to mid July

- reduced temperatures during July (negatively influencing either or both the bees and the forage) where the average, low and high temperatures for 2022 were 17°C, 7.4°C and 33.2°C, and for 2023 were 15°C, 5.7°C and 24.3°C

The July rainfall will have suppressed the temperature, but the second half of the month was also cooler than normal.

I’ve done some reading on the impact of moisture on nectar production. There’s quite a bit on the influence of humidity on both nectar production and the sugar concentration of the nectar, but these are all short term effects.

Recent rainfall is known to stimulate nectar production in plants such as rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis; Keasar et al., 2008) but I’ve yet to find much on stimulatory effects of rainfall over a longer period.

If your bees have finished for the year and you want some winter reading perhaps try Lawson and Rands’ (2019) review of rainfall on plant-pollinator interactions. In particular they highlight that rainfall can dilute nectar, making it less rewarding for (at least some) pollinators. Rainfall, and lower temperatures, also significantly reduce foraging activity (and, to my surprise, nurse bee activity within the hive; Riessberger and Crailsheim, 1997).

I think this is a topic I’ll have to return to …

Does any of this help?

Possibly not.

Other than the satisfaction of knowing having a vague idea what went wrong, since it was probably poor weather there’s not a lot that could be done to avoid the situation, other than moving to another county … or country … or continent.

But, assuming it was the weather and if there was reliable long-range (i.e. ~2 months or more) weather forecasting I can think of other ways to productively ‘rescue’ the latter half of the season.

You could – as suggested above – move your bees.

That’s easier said than done, involves lots of work/travel and probably also requires reliable long-range local weather forecasts … but hey, “if you’re gonna dream, dream big” 😉 .

Alternatively, you could make bees, not honey.

Had I known that the second half of this season was going to be ‘total pants’ I’d have completely abandoned honey production and instead split the colonies to produce many more nucs for overwintering.

With a concerted effort during the good weather in May/June it would have been relatively straightforward to get sufficient queens mated. The soon-to-be-unemployed honey production colonies could be split, each producing several nucs.

Inevitably this would then involve a bit of frame juggling to ensure the nucs didn’t get ‘overcooked’ before the onset of autumn, that extra work being compensated by the ability to produce more nucs from harder initial splits of the colonies.

Or you could do something for the bees, such as using queen trapping to enforce a brood break, apply a midseason miticide treatment and have the satisfaction of them going into autumn with very low mite and virus levels.

The same thing could be achieved, coupled with a full box of new comb, by combining a shook swarm and miticide treatment.

The end is nigh

The removal of the summer honey marks the end of the practical beekeeping season for me. Having cleared the supers {{13}} I checked the frames. There was a small amount of fresh nectar in a few of them, though nothing like enough to justify leaving them for another week or two.

Not so much a nectar flow as a pathetic dribble.

Brood boxes were looking very ‘end of season’. Almost no drone brood {{14}} and most of the drone comb was backfilled with nectar or sealed stores.

I failed to find the one queen I had yet to mark {{15}} so she and I will have that to look forward to next April.

I didn’t inspect the colonies but I did pull a few frames to work out where the edge of the brood nest was so I could place the Apivar strips correctly.

Then all that was left to do was to replace the queen excluder and add a split block of fondant, with either an empty super (Of which I have a surfeit 🙁 ) or an eke and an inverted perspex crownboard to provide ‘headspace’ for the block.

Adios bees … I’ll be back in a few weeks to reposition the Apivar 🙂 .

Notes

This is not the place for a long discussion about the economics of beekeeping here. In terms of sales, one super (assume ~10 kg of extracted honey) is worth about the same as an overwintered nuc. My suggestion to ‘make bees’ instead of honey achieves three things:

- offset ‘losses’ from honey sales by selling nucs

- repopulate (and/or expand) your own apiaries with strong nucs next spring

- provide local bees for beekeepers, rather than them relying on imports

With a conservative 3- or even 4-way split of a midsummer production colony all of the above should be achievable … if you know how to rear queens and have enough nuc boxes 😉 .

References

Keasar, T., Sadeh, A., and Shmida, A. (2008) Variability in nectar production and standing crop, and their relation to pollinator visits in a Mediterranean shrub. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 2: 117–123 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-008-9040-9.

Lawson, D.A., and Rands, S.A. (2019) The effects of rainfall on plant–pollinator interactions. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 13: 561–569 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-019-09686-z.

Riessberger, U., and Crailsheim, K. (1997) Short-term effect of different weather conditions upon the behaviour of forager and nurse honey bees (Apis mellifera carnica Pollmann). Apidologie 28: 411–426 http://dx.doi.org/10.1051/apido:19970608.

{{1}}: Other resolutions are available, but we’re talking local and that’s about as local as it gets.

{{2}}: At least as far a I can tell … I bet they are for a fee though. They have predictive value for agronomists.

{{3}}: Shower? What’s the collective noun for weather stations?

{{4}}: Where’s the fun in that?

{{5}}: You need lots of space to get these recorded accurately.

{{6}}: Long story short … no.

{{7}}: Or ’summer’ as we like to call it.

{{8}}: On the west coast.

{{9}}: And I don’t have the time or energy to look through the older numbers and work out the exact hive numbers I had each summer.

{{10}}: Unlike 2023, no need to sell any organs, or force the kids into indentured service.

{{11}}: A relative term, it was still pathetic.

{{12}}: Depending whether it’s early or late in the day … or perhaps before or after lunch.

{{13}}: Some were already vacant!

{{14}}: The only hive with sealed drone brood was headed by a pure native black queen.

{{15}}: Though, to be honest, it was a pretty cursory search by a demoralised and honey-less beekeeper.

Join the discussion ...