What is local?

That bubbling cesspool of hate, conspiracy theories and misogyny - the laughingly misnamed social media platform Twitter X - reminded me that the 21st of October was National Honey Day.

Monday 21st October is National Honey Day. The BBKA would like to celebrate the delicious diversity of local UK honey bought directly from local beekeepers.#honey #localhoney pic.twitter.com/yQPmeujtlR

— BBKA (@britishbee) October 21, 2024

At least, it was according to the BBKA, though it doesn't make it onto the list of Awareness days which includes such classics as International Traffic Light Day (August 5th {{1}}), Finland's National Jealousy Day {{2}} and - on the day this post appears - National Vote Early Day in the USA {{3}}.

Anyway, enough nonsense.

The BBKA should have called their initiative National Local Honey Day as it's really designed to encourage consumers to buy local honey.

This initiative was launched a couple of years ago, and they produce and distribute some attractive logos, graphics and posters to promote the day.

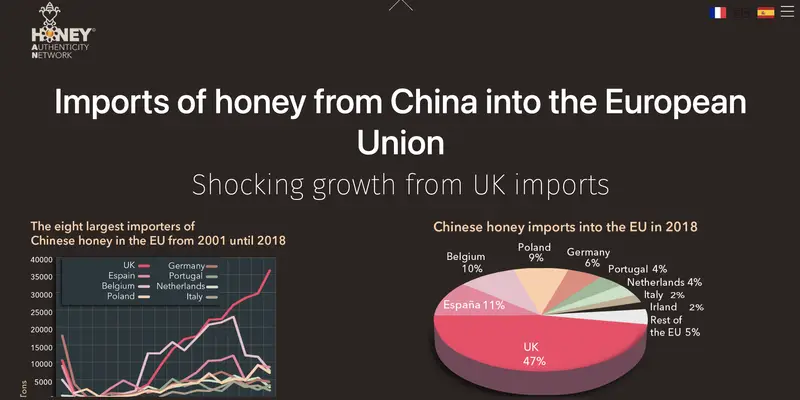

They also link to the Honey Authentication Network, which has nicely designed and infographic-rich website emphasising the scale of international honey fraud.

I'll return to this later as a quick check in my local supermarket suggests these initiatives are not working.

What is local?

The BBKA defined local in terms of community and 'a few miles' ... but it's clear there is no precise definition. Had there been it would have saved me several hours and at least one late night of two-fingered typing ...

'Local' is a term widely used by beekeepers - local honey, local bees, local association - without ever really being defined.

Is it one of those words that really means anything to anyone, and may mean different things to the person writing/saying it, and the person reading/hearing it?

It sounds good, doesn't it?

Of, relating to, inhabiting, or existing in a particular place or region.

But we need a sense of scale here.

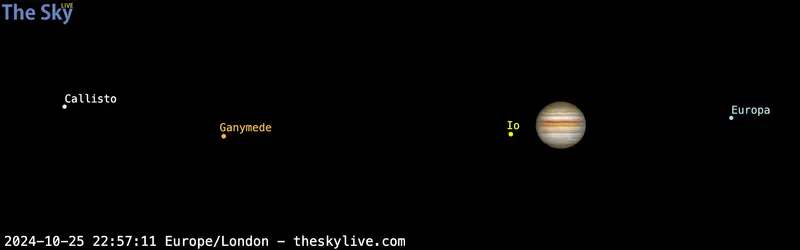

As Storm Ashley rolled off into the North Sea in the early hours of Monday morning, the sky cleared and there were wonderful views of Jupiter and the Galilaen moons; Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

To me, Ganymede didn't 'feel' particularly local (we're currently 660 million kilometres away; 6.6 x 108 km), unless compared to Aldebran - visible to the right of Jupiter - which is 66 light years away (6.2 x 1014 km i.e. one million times further away).

These things are all relative.

What does local mean to beekeepers, or to our bees?

Why does local not only sound good, but is good as far as bees, honey and associations are concerned?

Local association

Beekeeping looks easy.

I mean, how difficult can it be to plonk a box at the bottom of the garden, fill it with bees, and harvest a few dozen jars of delicious golden honey a couple of times a year?

Yes, I know, the books and websites have all sorts of dire warnings about swarming, feeding, pests and parasites.

Really? I mean, come on! They're just insects.

Bees have been around for millions of years, so they're bound to be able to cope with your inexperienced fumblings, and the usual beginners' faux pas.

What's more, after spending an evening or two watching YouTube videos from that portly beekeeper (they all look overweight in those funny suits, don't they?) in Louisiana you're feeling pretty confident.

US readers could substitute 'Roxburghshire' for Louisiana, chosen - not because it gives those from Roxburghshire a giggle when pronounced by non-locals (Roks-bru-shu ... the 'gh' and 'ire' are pretty-much ignored) - but because the climate is wildly different from Louisiana. Theres also at least one portly beekeeper in Roxburghshire ... I know as now live within swarming distance (< 5 km) of Roxburgh, the ancient county town.

The point I'm trying to make is that, although bees are kept all over the world, the places (localities) in which they are kept can be very different.

A Louisianan beginner, self-taught from a Roxburghshire beekeepers website, might wait in vain for a broodless period in the winter to treat with trickled oxalic acid solution. Likewise, a Roxburghshire beekeeper, schooled on the Louisianan's YouTube videos, would likely fail to find anywhere that sells a slatted rack ... let alone experience the hot summers that justify its use.

This is where the local beekeeping association can be a huge help. Since the association members are all from the same locality they can provide training and advice that's tailored to the local conditions.

Although this might not make beekeeping easy in the first year or two, it certainly makes it easier.

Big or small

The help will reflect the experience of the local beekeepers; is there a pronounced June gap, does the ivy or balsam provide a useful late-summer boost? When does the oil seed rape usually yield? Is there a pronounced rain shadow because of the mountains to the west? Is it warm enough to treat with Apiguard in the Autumn? {{4}} How cold are the winters, and when are the colonies reliable broodless?

The likelihood is that these things are broadly similar within the area the local association draws its members from.

Different associations cover more or less territory, and some associations have partial (or greater) overlaps in their areas. Sometimes this is a historical quirk, reflecting now long-forgotten mergers, or expansions as the nearby towns became more populous. At other times, these overlaps are due to bitter feuds - often far from forgotten - that resulted in the scission of an original association.

Choose wisely 😉.

I belong to several associations, each largely serving geographically-sensible areas - Tayside and Fife (North and South of the River Tay in the East of Scotland), and Lochaber on the remote West coast. Having recently moved house, I'll shortly be picking the brains of the beekeepers in the Scottish Borders in the hope of not having to learn things the hard way (i.e. by experience).

The climate, the forage, and the bees able to survive the former and exploit the latter, are very different, despite the East and West coasts being only 150 miles apart.

For example, my West coast bees experienced 2+ metres of rain a year and had no agricultural crops within 25 miles. In contrast, Fife on the East coast gets about one third the amount of rain and is one of the most heavily farmed areas in Scotland.

If you are a beginner, seek out your local association, join - even if you're not naturally a 'joiner' - and attend a few of their meetings.

Beekeepers are often weird, but almost always in a nice way. Ask questions ... you'll never be short of answers, and not all of them will be contradictory 😉.

Whatever you learn from books, YouTube or the web, it's very unlikely that the information will be better tailored to the local environment that your bees occupy.

Speaking of which ...

Local bees

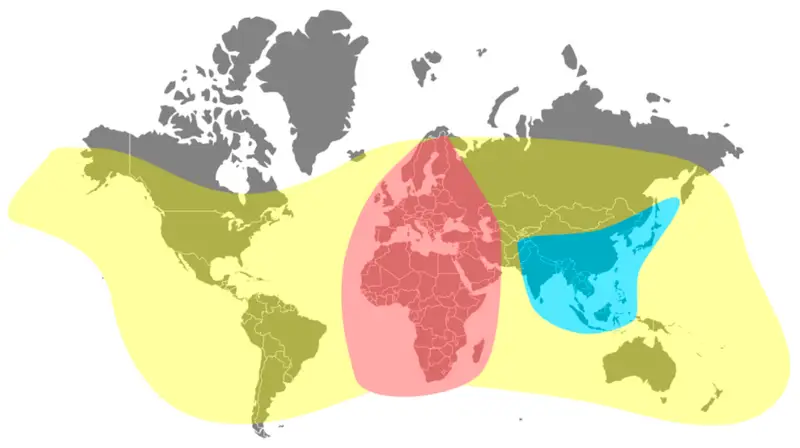

The natural range of the Western honey bee is Africa and Europe, but they are now distributed globally due to the activities of beekeepers. We have moved colonies for pollination or honey production and exchanged or transported favoured strains (for productivity or disease resistance, for example) for millennia.

These honey bees are all the same species (Apis mellifera), but the very fact that 'favoured strains' have been moved around indicates that not all honey bees are identical. My bees on the West coast of Scotland - a cool, damp area with limited forage at certain times of the season - are small, dark, hairy and downright mean very frugal with their stores.

My Heinz mongrels ("57 varieties") in Fife are yellower, a bit bigger and a bit less frugal. A few miles down the road is a beekeeper who favours Italian bees, so buys imported ligustica queens that head large colonies of very calm, pale yellow bees ... they are a lot less frugal with their stores, and autumn feeding involves an apiary visit from a tanker.

But there are other differences in addition to productivity, calmness and frugality.

Those imported Italian queens will bring with them their own strains of deformed wing (DWV) and other virus strains. The 'local' Varroa in Fife will pick these viruses up and transport them to neighbouring colonies when spread during robbing, swarming or drifting.

Invisible differences

Imported bees are rarely tested for anything other than visible pests and pathogens such as small hive beetle, and we know that there are viruses in some UK colonies that are most closely related to those where the bees or queens were imported from.

Finally, all of those differences in traits - calmness, frugality, productivity etc. - involve underlying physiological, biochemical and genetic differences.

They're all honey bees, but they are not all the same.

Bees become adapted to the area in which they live.

I've previously discussed two relevant studies that clearly demonstrate the adaptions carried by local bees, and the benefits that they confer.

When the proteins of bees from Saskatchewan are compared with those from warmer climates, such as Hawaii, these differences become apparent ... cold-adapted Canadian bees express higher levels of the proteins involved in heat production, whereas the Hawaiian bees express more proteins involved in recovery from heat damage (Parker et al., 2017).

These differences probably aren't so large that Saskatchewan bees transplanted to Hawaii wouldn't survive, but they probably would not do as well as the local Hawaiian bees, and vice versa. Of course, over time, transplanted Saskatchewan bees would be expected to adapt to the warmer environment ... assuming that they did survive.

But that's not guaranteed.

Other studies have shown that locally adapted bees survive better than imported bees. One study (described in detail in the link above, so I'm going to be brief) involved relocating ~600 colonies of bees within Europe {{5}}, and comparing their performance of sister colonies in their home apiary and their new location.

Colonies headed by local queens survived longer in the absence of Varroa management, and the colonies were ~20% stronger, resulting in better overwinter survival (Büchler et al., 2014 and Hatjina et al., 2014).

So, local bees are better ... but that wasn't the question

It's important to remember that these studies do not indicate that a local mongrel colony will outperform a colony headed by an imported queen. The imported bees might be calmer, more productive - either in terms of honey or bee production - or better pollinators (yes, that varies as well).

What it means is that the imported queen/colony is likely to do less well than it would have done in its original location.

And, of course, careful selection of the local mongrels could well result in a strain that is as just as calm or productive as any imported colony.

But the question was "What is local?" and, with regard to bees, I don't think I've come close to answering the question.

The Büchler study moved bees far shorter distances than that separating Saskatchewan and Hawaii (~5,600 km), but they did not provide a breakdown of performance vs. distance. This is understandable ... the differences observed, in disease resistance and survival, were not enormous. To definitively demonstrate local benefits over shorter distances would have needed tens of thousands of colonies.

So, let me answer the question differently.

When I moved from the Midlands to the East of Scotland (~450 km) I also moved my bees. They were mongrels, but had been selected over 5-6 years to suit my beekeeping. They had also been regularly tested for viruses, so I was reasonably comfortable I wouldn't be importing any weird exotics to the East of Scotland {{6}}. In due course I'll be moving these bees the ~90 km to the Scottish Borders.

The within Scotland move I consider 'local' - the climates are pretty much the same, and the areas both have extensive, and broadly similar, agriculture. In contrast, the initial move from the Midlands to Scotland probably wasn't 'local', but I felt the benefits of not starting the selection process from scratch outweighed the benefits of sourcing Scottish bees once I'd moved.

However, the 450 km makes them a lot more local than the ligustica queens imported from Italy.

Of the three things I'm covering - associations, bees and honey - I think local bees is the most difficult to define.

Local honey

On National (Local) Honey Day I visited two local supermarkets and looked at their offerings.

Oh dear 😞.

Both contained a range of localish (in the broadest sense of the word), local-looking and generic honey, with the vast majority being either all imported, or probably imported. The labelling regulations mean it's not always possible to be certain about the origin ...

Produce of EU and non-EU countries

... means it could be an exquisite blend of Spanish wildflower honey and Chilean honey from the foothills of the Andes.

However, it's more likely to be an undefined proportion (1%, 5%, 15%?) of honey from somewhere in Europe (assuming any is from the EU) - though did it originate in the EU? - bulked up with something sweet and syrupy imported from elsewhere, probably China.

And, if the syrupy add-ins weren't imported from China, they were probably produced in China, and shipped via one or more intermediate countries to obscure their provenance.

Do any of these jars have pagodas on the label?

Are they labelled 蜂蜜?

Nope. Instead they often have bucolic scenes of an English wildflower meadow {{7}}, or a simple sketch of a WBC hive (which, despite looking a little like a pagoda is a classic UK hive type) on a shiny gold background.

And just look at that 'best before' date ... lots of filtering I suspect.

Fake news

The UK imports 80-90% of the honey consumed here. I've previously written extensively about the large-scale international fraud in "honey" production. Recent testing of some honey packed and exported from the UK for the European market showed that all was 'suspicious', and that parallel testing indicated that ~50% of all honey imported into Europe was likely to be adulterated with rice syrup, or similar.

But this 'fake news', despite being widely publicised, is largely ignored.

In fact, going by the jars 'missing' from the shelves - presumably purchased - the customer prefers the 'honey' at 75 p rather than the Scottish honey at £8.50 on the shelf above.

And finally, before I stop alternately ranting and sobbing quietly, it's worth remembering the 'Beewash' credentials of honey and honey bees. Almost anything can be justified if it benefits bees or beekeeping.

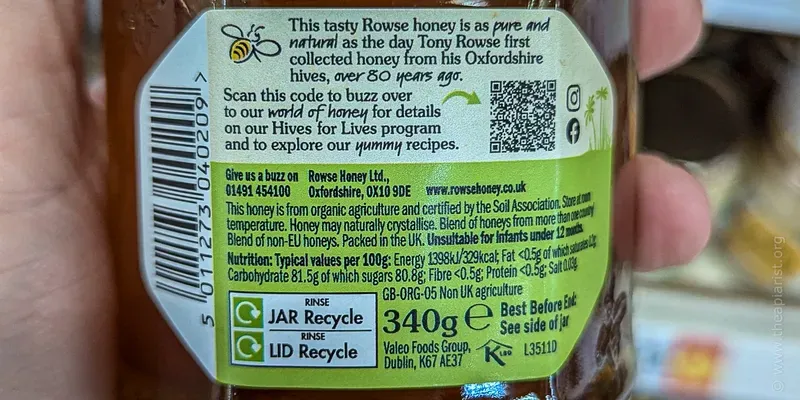

Rowse, one of the major honey packers in the UK, advertises its Pure Organic Honey with the words "Protecting bees and beekeepers" ... well, yes they do, but that doesn't alter the fact that the honey in those jars is all imported ... put your glasses on and read the fine print ...

This tasty Rowse honey is as pure and natural as the day Tony Rowse first collected honey from his Oxfordshire hives, over 80 years ago

... but further down the jar, in smaller lettering:

Blend of honeys from more than one country. Blend of non-EU honeys.

Ho hum 😞.

I'm sure Rowse would argue that their profits from selling imported honey (or is it "honey") supports local, or at least national, beekeeping. However, as a local beekeeper, that feels a little contrived.

Personal experience

I produce a small(ish) amount of honey each year.

Enough to justify buying jars by the pallet load, but not enough to get pallets delivered all that frequently.

Enough so that jarring a bulk order makes for a tedious evening or two, but not enough to make me spend the money for a jarring machine.

Of course, the latter may simply reflect how mean I am, rather than the scale of my operation 😉.

About 80% of my honey is sold within 10-15 miles of the apiary that it is produced in, with the remainder sold on the other side of Scotland. On the East coast, all the outlets describe the honey as 'local', and there's no doubt that it is. The jars carry a QR code indicating their provenance, so the customer can read about where the bees have been foraging.

In the more remote outlet (where I also sell local honey produced within a few miles of the store), my East coast honey sells alongside other honeys from Scotland, but the storekeeper can at least honestly claim that the honey is produced by a local beekeeper, if not local bees.

So what is local?

It's pretty clear from the above that it's only the local beekeeping association that is easy to define and - even then - the geographic area may be rather vague, and certainly may not be exclusive.

Local bees could probably be defined in terms of their pathogens, physiology, biochemistry and genetics, but no one is seriously suggesting that this would be useful ... or, in fact, readily achievable. However, it's almost inevitable that these features would exhibit a gradation of differences and a definition of local would need to justify at what point the bees were sufficiently different to no longer be considered local.

What you clearly cannot do is qualify local bees in terms of local beekeeping associations. The latter have some sort of geographic boundaries, however ill-defined, whereas the bees - once adapted to a particular location - will differ in relation to changes in the selective environmental factors like temperature, rainfall, forage availability etc.

And local honey? Who knows? One thing that was notable in the supermarkets I visited is that neither contained any truly local honey i.e. produced within a handful of miles of the supermarket (the BBKA definition). Both offered Scottish honey - so 'nationally' local I guess - though the jars contained no further clue to pin down their geography. The remainder - perhaps 95% by number and 80+% by brand - were either partially (a blend of some sort) or entirely imported. Almost all contained non-EU honey and very few contained honey from the UK.

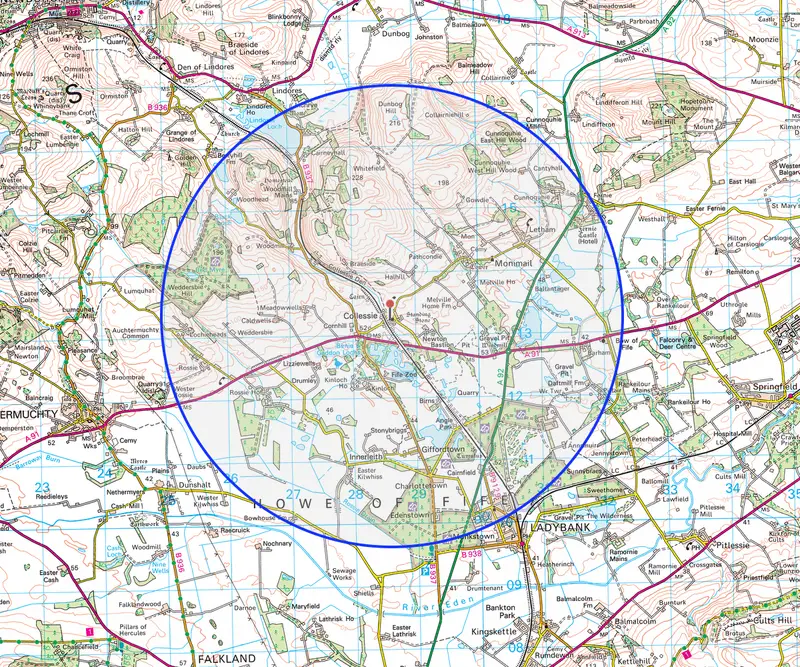

I know the arguments for why supermarkets stock these types of honey - supply reliability, long shelf life, uniform appearance and flavour etc - to keep the customer satisfied. However, I'm dismayed that the customer has no option to purchase a real local product, something that provides a unique snapshot of what was flowering in a little 12 km2 patch {{8}} of nearby countryside (or for that matter urban environment, where bees travel less far to forage, and a greater range of forage is usually available).

A customer wanting that sort of honey has to shop elsewhere ... but many probably don't even know it exists.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained

Sponsor The Apiarist

The Apiarist covers 'the science, art and practice of sustainable beekeeping ... so much more than honey' and I write to help understand the meaning of life local, if nothing else.

If you found this post illuminating, useful or amusing then please consider sponsoring The Apiarist.

Sponsorship costs less than £1/week annually, or currently little more than a large cappucino monthly. Sponsors help ensure the weekly posts appear, receive an irregular (approximately monthly) newsletter, and have access to an increasing number of sponsor-only content ... those starred ⭐ in the lists of posts.

Alternatively, you can help reduce my caffeine overdraft ... and please spread the word to encourage others to subscribe.

Thank you.

References

Beaurepaire, A., Piot, N., Doublet, V., Antunez, K., Campbell, E., Chantawannakul, P., et al. (2020) Diversity and Global Distribution of Viruses of the Western Honey Bee, Apis mellifera. Insects 11: 239 https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4450/11/4/239.

Büchler, R., Costa, C., Hatjina, F., Andonov, S., Meixner, M.D., Conte, Y.L., et al. (2014) The influence of genetic origin and its interaction with environmental effects on the survival of Apis mellifera L. colonies in Europe. Journal of Apicultural Research 53: 205–214 https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.53.2.03.

Hatjina, F., Costa, C., Büchler, R., Uzunov, A., Drazic, M., Filipi, J., et al. (2014) Population dynamics of European honey bee genotypes under different environmental conditions. Journal of Apicultural Research 53: 233–247 https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.53.2.05.

Parker, R., Melathopoulos, A.P., White, R., Pernal, S.F., Guarna, M.M., and Foster, L.J. (2010) Ecological Adaptation of Diverse Honey Bee (Apis mellifera) Populations. PLOS ONE 5: e11096 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0011096.

{{1}}: A date shared with National Underwear Day in the USA

{{2}}: 1st November, when every Finnish citizen’s taxable income is revealed, searchable by anyone.

{{3}}: Just in case you weren't aware that there's an election looming ...

{{4}}: Often not, but people nevertheless use it.

{{5}}: These colonies were from ~21 apiaries, and they were relocated randomly, so not just moving bees from Southern climates to Northern.

{{6}}: And, as far as I know, this was the case 😄.

{{7}}: There's a clue for starters ... wildflower meadows are vanishingly rare in the UK.

{{8}}: I'm assuming a foraging radius of ~2 km.

Join the discussion ...