Weight for spring

I’m currently reading The Lives of Bees by Thomas Seeley. It’s a very good account of honey bee colonies in the wild.

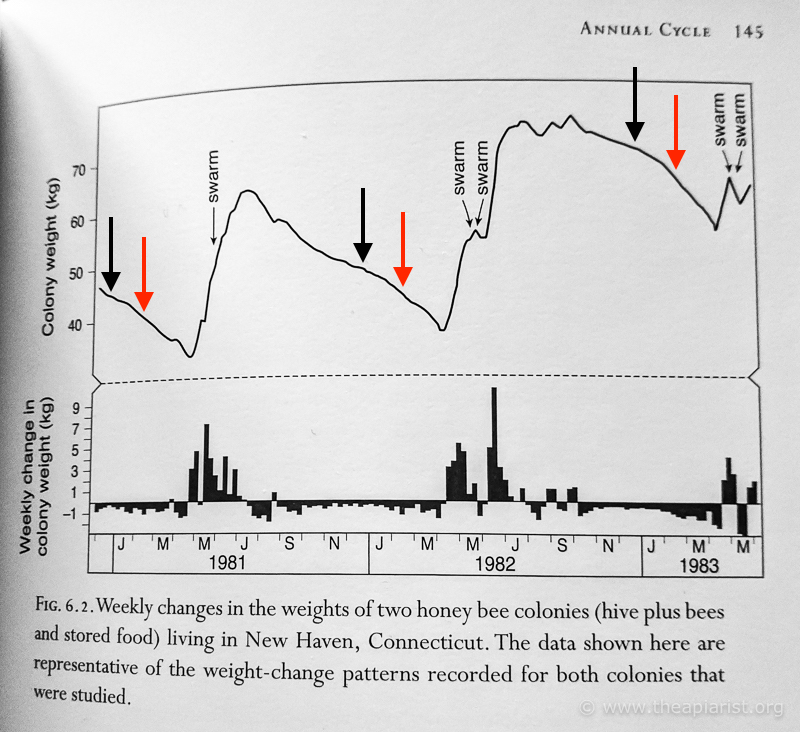

In the book Seeley describes studies he conducted in the early-80’s on the changes in weight of unmanaged colonies during the season {{1}}.

One particular figure caught my attention as I was off to the apiary to heft {{2}} some hives and check on the levels of stores.

Colony weight (top) and weekly weight change (lower). Black arrows midwinter, red arrows early spring.

The upper panel shows the overall hive weight over a period of ~30 months, including three successive winters. I’ve butchered annotated the figure with black arrows to mark the approximate position of the winter solstice and added red arrows to indicate early spring (approximately mid-February i.e. about now) {{3}}.

Look carefully at the slope of the line. In each year it steepens in early spring.

Shedding pounds

During the winter the colony survives on its reserves. There’s no forage available and/or it’s too cold to fly anyway, so the colony has to use honey stores to keep the worker bees alive.

In late autumn and early winter they can get by using minimal amounts of stores, just sufficient to keep metabolic activity of the bees high enough to maintain a cluster temperature of ~10°C.

All of this uses stores and so the colony gradually loses weight.

The weekly weight gained and lost is shown in the lower panel. In 1981/82, with the exception of a tiny weight gain in late August, the colony lost weight every week from mid-July until mid-April (9 months!).

But from mid-April to early-July the colony literally piles on the pounds {{4}}.

To achieve this they need a strong population of worker bees. It’s not possible to collect that much nectar with just a few thousand bees. The colony must undergo a large population expansion from the 5,000-10,000 bees that overwintered the colony to a summer workforce of 30,000+.

This expansion is not simply the addition of a further 20,000 bees. At the same time as the new workers are emerging the winter bees are dying off. The colony therefore needs to rear significantly more than 20,000 bees to be ready to exploit the summer nectar flow.

And, since it takes bees to make bees this means that the colony must rear repeated cycles of new workers starting in very early spring.

But you can’t rear brood at 10°C

Brood rearing requires a cluster temperature of ~35°C. This is achieved by the bees raising their metabolic activity, repeatedly flexing their flight muscles and generating heat.

All of which uses lots of energy … which, in turn, is derived from the honey stores.

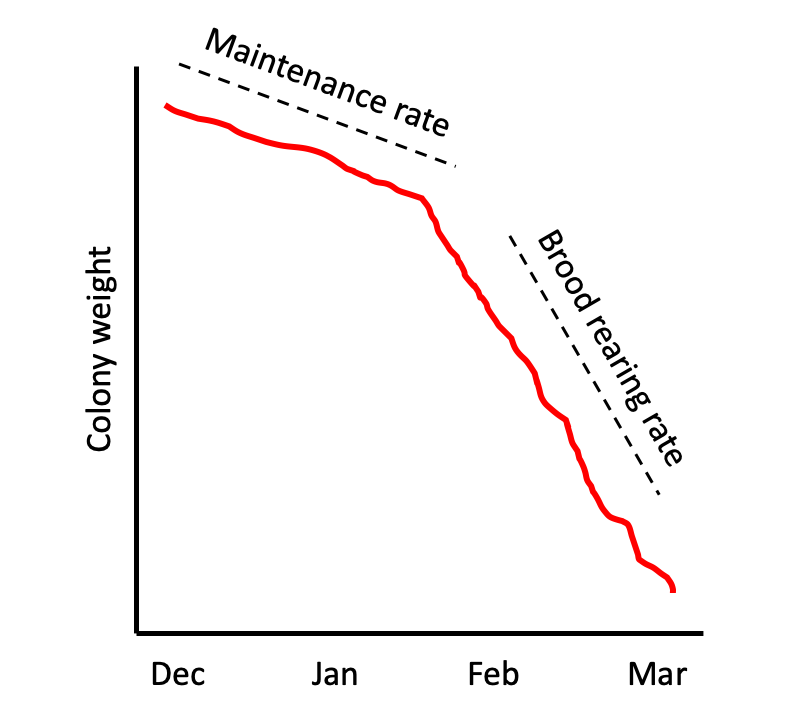

Which explains why, in early spring, the rate at which stores are consumed suddenly increases. And the rate at which the colony uses the stores is the weight lost per unit time i.e. the slope of the graph shown above, or below for emphasis.

Of course, some of the honey stores are also consumed by the developing larvae. How much presumably depends upon the amount of brood being reared and the external temperature.

Less brood requires less honey stores. Lower temperatures mean more energy must be expended to keep the brood at 35°C, so more stores are used.

Rearing brood also requires protein (pollen). Nearly 90 years ago Clayton Farrar studied the spring weight loss of colonies in Wisconsin maintained with or without pollen stores. Colonies unable to rear brood because they lacked pollen used ~50% less stores over the same period.

Thermoregulation is energetically costly and colonies must raise the temperature of the cluster to ~35°C in very early spring to rear sufficient brood to exploit the late spring nectar sources {{5}}. They need to maintain these elevated temperatures – using yet more stores up – until the spring nectar flows start.

The danger zone

All of which means that we’re currently approaching the danger zone when colonies are much more likely to starve to death if they have insufficient stores.

The next six to eight weeks or so are critical.

If they have ample stores they will rear plenty of brood.

If they have borderline levels of stores they might be able to maintain viability of the colony, but they’ll only achieve this by not rearing brood {{6}}.

If they start brood rearing and then run out of stores they will likely starve to death.

Winter chores

Every couple of weeks I check all of my colonies.

I confirm two things:

- the entrance is clear i.e. not blocked with the corpses of dead bees.

- the colony has sufficient stores for another few weeks.

This takes no more than one minute per colony and can be done whatever the weather, or even at night if you cannot get to the apiary in the short daylight hours.

The floors I favour have an L-shaped entrance tunnel which during extreme periods of confinement can get blocked with dead bees. A quick scrape with a bent piece of stiff wire clears them away.

Even ‘normal’ entrances should be checked as it’s surprising the number of corpses that can accumulate, particularly after a long period of very adverse weather when no undertaker bees are flying.

As an aside, assuming no brood rearing, a colony entering the winter with 25,000 bees will likely lose an average of ~150 bees a day before brood rearing starts again in earnest. They will not be lost at the same rate throughout the winter. Do not worry about the corpses (though it’s worth also noting that a strong, healthy colony should clear these).

Hefting the hive

The weight of the hive can be determined in at least three different ways:

- wealthy beekeepers will use an electronic hive monitoring system with integral scales. No need even to visit the apiary to check these 😉 Where’s the fun in that?

- thorough beekeepers will use set of digital luggage scales to weigh each side of the hive, summing the two figures and noting the total carefully in their meticulous hive records.

- experienced beekeepers will briefly lift the back of the hive off the stand and decide “Hmmm … OK” or “Hmmm … too light”. This is termed hefting the hive.

If this is your first winter I strongly recommend doing the second and the third method every time you visit your apiary.

The second method will provide confidence and real numbers. These are what really count.

Hefting the hive for comparison will, over time, provide the ‘feel’ needed to judge things without a set of scales.

Over time you’ll find you can judge things pretty well simply by hefting. I do this {{7}}, but only after removing the hive roof. I’ve got a variety of roofs in use – deep cedar monstrosities, dayglo polystyrene and lots of almost-weightless folded Correx – which, coupled with the variation in the number of boxes and the material they’re made from, complicates things too much.

Without the roof I find it a lot easier to judge.

Hmmm … too light

Anything that feels too light needs a fondant topup as soon as possible.

If you even think it feels too light it’s probably wise to add a block of fondant.

You need to use fondant as it’s probably too cold for bees to take down syrup. Fondant works, whatever the weather.

How much fondant should you add?

Look again at the hive weight loss per week in the early months of the year in the lower panel of the first graph. These colonies lost at least 1-1½ lb per week.

When will you next check them?

Do the maths as they say …

If you check them fortnightly you really need to add 1-2 kilograms which should be sufficient to get them through to the next check. Do not mess around with pathetic little 250g blocks of clingfilm-wrapped fondant. They might use that in three days …

You also don’t want to be opening the hive unnecessarily. Add a good-sized block and let them get on with things.

Recycle

Loads of supermarket foods are supplied in a variety of clear or semi-translucent plastic trays – chicken, mushrooms, tortellini, curry ready meals etc {{8}}. Throughout the season I wash these out and save them for use with the bees.

I stressed clear and semi-translucent as it helps to be able to tell how much of the fondant the bees have used up when you’re trying to judge whether they need any more.

Many of these trays are about 6″ x 4″ x 2″ which when packed with fondant conveniently weighs about a kilogram. I fill a range of these with fondant, cover them with a single sheet of clingfilm and write the weight on the clingfilm with a black marker pen.

Location, location, location

In the winter the goal should be to locate the fondant block as close as possible to the cluster.

This means directly over the cluster.

Not way off to one side because there are fewer bees on the top bars that are in the way.

There’s no point in adding fondant if you also force the bees to move to reach it.

You’ll need an eke (or a nice reversible, insulated crownboard) to provide the ‘headspace’ to accommodate the fondant block {{9}}.

Don’t delay.

Don’t wait for a ‘nice’ day.

You’ve decided the colony is worryingly light so deal with it there and then.

Remove the roof and the crownboard. If it’s cold, windy or wet the bees are going to be reluctant to fly. Don’t worry, you’re helping them. You’ll do more harm by not feeding them than by exposing them to the elements for 30 seconds {{10}}.

Remove the clingfilm entirely {{11}} and invert the plastic tub directly over the top of the cluster.

Add the eke. Replace the crownboard, the top insulation and the roof.

Job done.

Crownboards with holes and queen excluders

Some crownboards have holes in them. Often these in the centre of the board.

It’s often recommended to add the fondant block above the hole in the crownboard. I think it’s better to place the fondant directly onto the top bars for the following reasons:

- the central hole in the crownboard is probably not above the cluster {{12}}. Why give them more work to do to collect the stores you’re providing?

- it’s cold above the crownboard. The bees are less likely to venture up there if it’s chilly and uninviting.

- fondant deliquesces (absorbs moisture) and can get distinctly sloppy when located in the humid headspace above the crownboard. In contrast, if the fondant is on the top bars of the frames any moisture absorbed softens the fondant surface at exactly the point where the bees are going to eat it anyway.

Finally, if there’s any reason you need to go through the brood box (before the fondant is finished) place the fondant on top of a queen excluder directly over the frames. Fondant has a tendency to stick down firmly to the top bars and it’s a nightmare to remove it to get to the frames. In contrast, if it is on a queen excluder you can easily lift it off.

You might not need to do this, but I learnt the hard way 🙁

{{1}}: This was prior to the introduction of Varroa to North America. An unmanaged colony is a wild-caught swarm housed in a Langstroth hive with no active management – swarm control, feeding etc. – and inspected rarely solely to monitor colony development.

{{2}}: To lift for the purpose of trying the weight … which the OED state was first used in c. 1816. Etymology from heft n. and heave … analogical: compare weave, weft, thieve, theft etc.

{{3}}: With apologies for the quality of the image. The original paper was published in Ecological Entomology. My library has a subscription … but only as far back as the end of the last century. Shame on the journal for keeping a paper published almost exactly 35 years ago behind a paywall!

{{4}}: Remember, these hives were in New Haven, Connecticut … the specific timing of nectar flows will vary depending upon location. In Scotland my colonies gain weight through May, usually lose weight in mid/late June and then build up again during the summer flows in July.

{{5}}: Which, in turn, are what are used to build big booming colonies that swarm = colony reproduction. Of course, for the beekeeper, it is these colonies that pile in lots of honey and are probably better able to defend themselves against both diseases and robbing.

{{6}}: Meaning the colonies will build up slowly when forage does become available and are unlikely to be strong enough exploit early nectar flows.

{{7}}: After years of weighing colonies and with a few linked up to an Arnia system.

{{8}}: These are examples and are not necessarily representative of my diet.

{{9}}: Use a spare super if you’ve nothing else, but consider packing the empty space with bubble wrap.

{{10}}: Generally, the worse the weather the less chance you’ll need the smoker.

{{11}}: Bees chew it to shreds and drag it down into the brood nest.

{{12}}: The winter cluster is often centre front of the hive.

Join the discussion ...