Time to deploy!

It’s early April. The weather is finally warming up and the crocus and snowdrops are long gone. Depending where you are in the UK the OSR may start flowering in the next fortnight or so.

All of which means that colonies should be expanding well and will probably start thinking of swarming in the next few weeks.

So … just like any normal season really.

Except that the Covid-19 pandemic means that this season is anything but normal.

Keep on keeping on

The clearest guidelines for good beekeeping practice during the Covid-19 pandemic are on the National Bee Unit website. Essentially it is business as usual with the caveats that good hygiene (personal and apiary) and social distancing must be maintained.

Specifically this excludes inspections with more than one person at the hive. Mentoring, at least the really useful “hands-on” mentoring, cannot continue.

A veil is no protection against aerosolised SARS-CoV-2. Don’t even think about risking it.

This means that there will be a lot of new beekeepers (those that acquired bees this year or late last season) inspecting colonies without the benefit of help and advice immediately to hand.

Mistakes will be made.

Queen cells will be missed.

Colonies will swarm {{1}}.

It’s too early to say whether the current restrictions on society are going to be sufficient to reduce coronavirus spread in the community. It’s clear that some are still flouting the rules. More stringent measures may be needed. For beekeepers who keep their bees in out apiaries, the most concerning would be a very restrictive movement ban. In China and (probably) Italy these measures proved to be effective, although damaging to beekeeping, so the precedent is established.

Many hives and apiaries are already poorly managed {{2}}. I would expect that additional coronavirus-related restrictions would only increase the numbers of colonies allowed to “fend for themselves” over the coming season.

Which brings me back to swarming.

Swarmtastic

The final point of advice on the NBU website is specifically about swarms and swarm management:

You should use husbandry techniques to minimise swarming. If you have to respond to collect a swarm you need to ensure that you use the guidelines on social distancing when collecting the swarm. If that is not possible, then the swarm then should not be collected. Therefore trying to prevent swarms is the best approach.

Collecting swarms can be difficult enough at the best of times {{3}}. And cutouts of established colonies are even worse.

In normal years I always prefer to reduce the swarms I might be called to {{4}} by setting out bait hives.

Let the bees do the work.

Then all you need do is collect them once they’re all neatly tucked away in a hive busy drawing comb.

This year, with who-knows-what happening next, I’ll be setting out more bait hives than usual with the expectation that there may well be additional swarms.

If they’re successful I’ll have more bees to deal with when the ‘old normal’ finally returns. If they remain unused then all I’ve lost is the tiny investment of time made in April to set them out.

Not just any dark box

I’ve discussed the well-established ‘design features’ of a good bait hive several times in the past. Fortunately the requirements are easy to meet.

- A dark empty void with a volume of about 40 litres.

- A solid floor.

- A small entrance of about 10cm2, at the bottom of the void, ideally south facing.

- Something that ‘smells’ of bees.

- Ideally located well above the ground.

I ignore the last of these. I’d prefer to have an easy-to-reach bait hive to collect rather than struggle at the top of a ladder. If I wanted to do some vertically-challenging beekeeping I’d go out and collect more swarms 😉

So, ignoring the final point, what I’ve described is the nearly perfect bait hive.

Those paying attention at the back will realise that it’s also a nearly perfect description of a single brood National hive.

How convenient 🙂

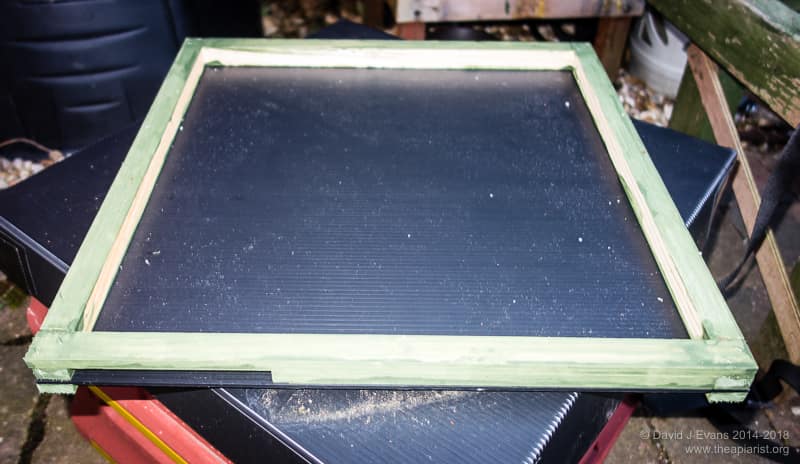

All of my bait hives are either single National brood boxes or two stacked National supers. The box does need a solid floor and a crownboard and roof. If you haven’t got a spare solid floor you can easily build them from Correx {{5}} for a few pence.

Alternatively, simply tape down a piece of cardboard or Correx over the mesh of an open mesh floor {{6}}. In some ways this is preferable as it’s convenient to be able to monitor Varroa levels after a swarm arrives.

Do not be tempted to use a nuc box as a bait hive. You can easily fit a small swarm into a brood box, but a really big prime swarm will not fit in a 5 frame nuc box.

Big swarms are better 🙂 {{7}}

More to the point, bees are genetically programmed to search for a void of about 40 litres, so many swarms will simply overlook your nuc box for a more spacious nest site.

What’s in the box?

No, this has nothing to do with Gwyneth Paltrow in Se7en.

How do you make your bait hive even more desirable to the scout bees that search out nest sites? How do you encourage those scouts to advertise the bait hive to their sister scouts? Remember, that it’s only once the scouts have reached a democratic consensus on the best local nest site that the bivouacked swarm will move in.

The brood box ideally smells of bees. If it has previously held a colony that might be sufficient.

However, a single old, dark brood frame pushed up against one sidewall not only provides the necessary ‘bee smell’, but also gives the incoming queen space to immediately start laying {{8}}.

You can increase the attractiveness by adding a couple of drops of lemongrass oil to the top bar of this dark brood frame. Lemongrass oil mimics the pheromone produced from the Nasonov gland. There’s no need to Splash it all over … just a drop or two, replenished every couple of weeks. I usually soak the end of a cotton bud, and lay it along the frame top bar.

The old brood frame must not contain stores – you’re trying to attract scouts, not robbers.

The incoming swarm will be keen to draw fresh comb for the queen to lay up with eggs. Whilst you can simply provide some frames and foundation, this has two disadvantages:

- the vertical sheets of foundation effectively make the void appear smaller than it really is. The scout bees estimate the volume by walking around the perimeter and taking short internal flights. If they crash into a sheet of foundation during the flight the box will seem smaller than it really is.

- foundation costs money. Quite significant amounts of money if you are setting out half a dozen bait hives. Sure, they’ll use it but – like putting a new carpet into a house you’re trying to sell – it’s certainly not the deal-clincher.

No foundation for that

Rather than filling the box with about £10 worth of premium foundation, a far better idea is to use foundationless frames. Importantly these provide the bees somewhere to draw new comb whilst not reducing the apparent volume of the brood box.

If you’ve not used foundationless frames before, a bait hive is an ideal time to give them a try.

There are two things you should be on the lookout for. The first is that the bait hive is horizontal {{9}}. Bees draw comb vertically down, so if the hive slopes there’s a good chance the comb will be drawn at an angle to the top bar.

And that’s just plain irritating … because it’s avoidable with a bit of care.

The second thing is that the colony needs checking as it starts to draw comb. Sometimes the bees ignore your helpful lollipop stick ‘starter strips’ and decide to go their own way, filling the box with cross comb.

Beautiful … but equally irritating 🙂

Final touches

For real convenience I leave my bait hives ready to move from wherever they’re sited to my quarantine apiary (I’ll deal with both these points in a second).

Wedge the frames together with a small block of expanded cell foam so that they cannot shift about when the hive is moved.

And then strap the whole lot up tight so you can move them easily and quickly when you need to.

Bait hive location and relocation

Swarms tend to move relatively modest distances from the hives they, er, swarmed from. The initial bivouac is usually just a few metres away. The scout bees survey a wide area, certainly well over a mile in all directions. However, several studies have shown that bees generally choose to move a few hundred yards or less.

It’s therefore a good idea to have a bait hive that sort of distance from your own apiaries.

Or even tucked away in the corner of the apiary itself.

I’ve had bees move out of one box, bivouac a short distance away and then occupy a bait hive on a hive stand adjacent to the original hive.

It’s probably definitely poor form to position a bait hive a short distance from someone else’s apiary 😉

But there’s nothing stopping you putting a bait hive at the bottom of your garden or – whilst maintaining social distancing of course – in the gardens of friends and family.

If you want to move a swarm that has occupied a bait hive the usual “less than 3 feet or more than 3 miles” rule applies unless you move them within the first couple of days of arrival. Swarms have an interesting plasticity of spatial memory (which deserves a post of its own) but will have fully reorientated to the bait hive location within a few days.

So, if the bait hive is in grandma’s garden, but grandma doesn’t want bees permanently, you need to move them promptly … or move them over three miles.

Or move grandma 😉

Lucky dip

Swarms, whether dropped into a skep or attracted to a bait hive, are a bit of a lucky dip. Now and again you get a fantastic prize, but often it’s of rather low value.

The good ones are great, but even the poor ones can be used.

But there’s an additional benefit … every one that arrives self-propelled in your bait hive is one less reported to the BBKA “swarm line” or that becomes an unwelcome tenant in the eaves of a house {{10}}.

As long as they’re healthy, even a bad tempered colony headed by a queen with a poor laying pattern, can usefully be united to create a stronger colony to exploit late season nectar.

But they must be healthy.

Swarms will potentially have a reasonably high mite count and will probably need treating within a week of arrival in the bait hive {{11}}. Dribbled or vaporised oxalic acid/Api-Bioxal would be my choice; it’s effective when the colony has no sealed brood {{12}} and requires a single treatment.

But swarms can bring even more unwelcome payloads than Varroa mites. If you keep bees in an area where foulbroods are established be extremely careful to confirm that the arriving swarm isn’t affected. This requires letting the colony rear brood while isolated in a quarantine apiary.

How do you know whether there are problems with foulbroods in your area? Register your apiary on Beebase and talk to your local bee inspector.

My bait hives go out in the second or third week of April … but I’m on the cool east coast of Scotland. When I lived in the Midlands they used to be deployed in early April. If you’re in the balmy south they should probably be out already {{13}}.

What are you waiting for 😉 ?

{{1}}: Although colonies in their first year with a new queen may not swarm, some do.

{{2}}: Not yours obviously! Or mine. But a surprising number of hives are not looked after properly, or rarely inspected. BBKA and local association swarm lines take hundreds of calls every year about lost swarms. And bumble bees, solitary bees, wasps etc. …

{{3}}: Not all are hanging in a football-sized clump on a waist-high branch with good access.

{{4}}: Or that might bother others.

{{5}}: The stuff they make For Sale signs from.

{{6}}: It does need to be taped down … if you don’t it will lift and move when there is a strong breeze. The inside of the bait hive should be dark and welcoming.

{{7}}: Many small swarms are casts or after-swarms, headed by a virgin queen.

{{8}}: Assuming it’s a prime swarm with a mated queen.

{{9}}: At least in the plane perpendicular to the top bars.

{{10}}: And every one captured is one less that will otherwise probably perish … 75% of swarms do not survive their first winter.

{{11}}: Remember, they’ve almost certainly originated from a managed colony where swarm prevention management was unsuccessful. It’s therefore quite likely that disease management was also sub-optimal.

{{12}}: Which, within a week of arrival, it won’t have.

{{13}}: I’m pretty sure scout bees start scouting even before queen cells are developed.

Join the discussion ...