Tim Toady

Synopsis : The large number of beekeeping methods is both a benefit and – for beginners particularly – a distraction. Learn methods well enough to be confident when you apply them. Understand why they work and their pros and cons.

Introduction

In an earlier life as a junior academic I was generously given a crushingly boring administrative task. The details don’t matter {{1}} but it essentially involved populating a huge three-dimensional matrix. The matrix had to be re-populated annually … and, when I was allocated the task, manually.

To cut a long story short I taught myself some simple web-database computer programming. This automated the data collection and entry and saved me many weeks of tedious work.

This minor victory resulted in me:

- writing lots more code for my admin and research, and for my hobbies including beekeeping and photography. It’s been a really useful skill … and a lot of fun.

- inevitably being given an additional mundane task to fill the time I had ‘saved’ 🙁 {{2}}.

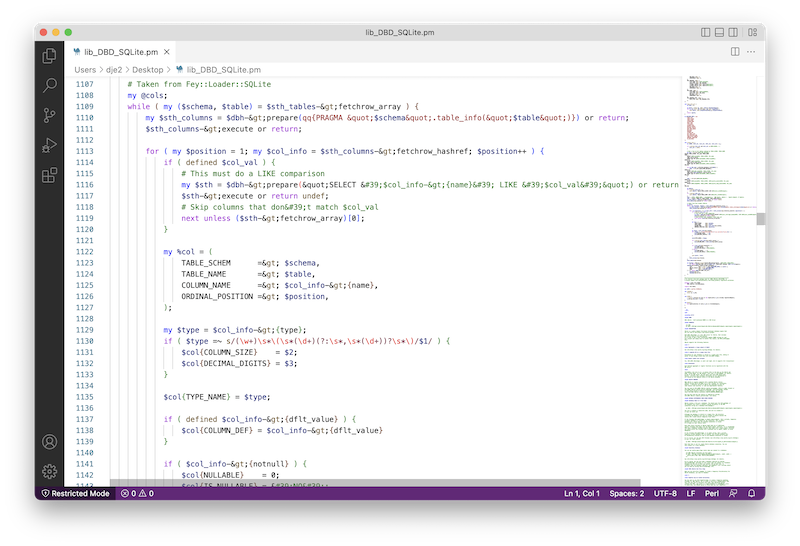

The programming language I used was perl. This is a simple scripting language, which although now superseded in popularity by things like python, remains very widely used. All proper computers {{3}} still have perl installed.

Perl is perfect for manipulating text-based records. The name is an acronym for ’practical extraction and reporting language’ … or perhaps ’pathetically eclectic rubbish lister’, the latter reflecting its use to manipulate text (‘garbage in, garbage out’ … ) {{4}}.

Perl was (and remains) powerful because it’s a very flexible language. You can achieve the same goal in many different ways.

This flexibility is reflected in the perl motto: ’There’s more than one way to do it’, which is abbreviated to TMTOWTDI.

TMTOWTDI is a mouthful of alphabet spaghetti, so for convenience is pronounced Tim Toady … the title of today’s post.

Why?

Because exactly the same acronym could be applied to lots of things in beekeeping.

Ask three beekeepers, get five answers

But one of the five is wrong because it involves ’brood and a half’.

Anyone who has attended an association meeting and naively asked a simple question will understand the title of this section.

’How do I … [insert routine beekeeping problem here] … ?’

The old and the wise, or perhaps the old or the wise, will recommend a series of solutions. Some will offer more than one.

Each will be different.

Many recommendations will be perfectly workable.

A few might be impractical.

At least one will be just plain wrong.

Confusingly … despite all being proffered solutions to the one question you asked, many will appear contradictory.

Do you move the queen away (the nucleus method) or leave the queen on the same site (Pagden’s artificial swarm) for swarm control? How can they both work if you do such very different things?

Ask twelve beekeepers, get nineteen answers (ONE IN ALL CAPS)

Internet discussion forums (fora?) are exactly the same, but may be less polite. This is due to the absence of the calming influence of tea and homemade cake. At least one answer will include a snippy suggestion to ’use the search facility first’.

Another will be VERY VERY SHOUTY … the respondent either disagrees vehemently or has misplaced the CAPS LOCK key.

Actually, in many ways internet discussion forums are a lot worse … though not for the reasons you might expect.

It’s not because they’re populated with a lot of cantankerous ageing beekeepers and arriviste know-it-alls.

They’re not {{5}}.

There are some hugely experienced and helpful beekeepers online, though they probably don’t answer first or most forcefully.

The internet is worse because the audience is bigger and is spread over a wider geographic area. This is a problem as beekeeping is effectively a local activity.

If you ask at a local association meeting there will be a smaller ‘audience’ and they should at least all have some experience of the particular conditions in your area.

But if you ask on Beesource, Včelařské fórum or the Beekeeping & Apiculture forum the answers may literally be from anywhere {{6}}. The advice you receive, whilst possibly valid, is likely to be most relevant where the responder lives … unless you’re lucky.

On one of the forums I irregularly frequent many contributors have their latitude and longitude coordinates (and sometimes plant hardiness zones) embedded in their .sig.

Geeky perhaps, but eminently sensible … {{7}}

Tim Toady beekeeping

Let’s consider a few of examples of Tim Toady beekeeping. I could have chosen almost any aspect of our hobby here, but I’ll stick with three that are all related to the position or fate of the queen.

Queen introduction

Perhaps this was a bad option to choose first. Queen introduction isn’t only about how you physically get the new queen safely into the hive e.g. in some form of temporary cage. It’s also about the state of the hive.

Is it queenless? How long has it been queenless and/or is there emerging brood present? Is the brood from the previous queen or from laying workers? Is it a full hive or a nuc … or mini-nuc?

And it’s about the state of the new queen.

Is she mated and laying, or is she a virgin? Perhaps she’s still in the queen cell? Is the queen the same (or a similar) strain to the hive being requeened? Is she in a cage of some sort? Are there attendants in the cage with her?

And all that’s before you consider whether it’s ‘better’ to use a push-in cage, a JzBz (or similar) cage or to omit the cage and just rely upon billowing clouds of acrid smelling smoke.

Uniting colonies

This blog is nothing if not ’bleeding-edge’ topical … now is the time to consider uniting understrength colonies, or those headed by very aged queens that may fail overwinter.

Uniting two weak colonies will not make a strong colony. However, uniting a strong with a weak colony will strengthen the former and possibly save the latter from potential winter loss (after you’ve paid for and applied the miticides and winter feed … D’oh!). You can always split off a nuc again in the spring.

All the above assumes that both colonies are healthy.

There are fewer ways of uniting colonies than queen introduction, and far fewer than the plethora of swarm control methods.

This is perhaps unsurprising as there are fewer component parts … hive A and hive B, with the eventual product being A/B.

Or perhaps B/A?

But which queen do you keep? {{8}}

And does the queenright hive go on top or underneath?

And how do you prevent the bees from fighting, but instead allow them to mingle gently?

Or do you simply spray them with a few squirts of Sea breeze air freshener, slap the boxes together and be done with it?

Swarm control

If you find queen cells in your colony – assuming they haven’t swarmed already – then you need to take action or the colony will possibly/probably/almost certainly/indubitably {{9}} swarm.

The primary goals of swarm control are to retain the workforce – the foragers – and the queen.

There are a lot of swarm control methods. Many of the effective ones involve the separation of the queen and hive bees (those yet to go on orientation flights) from the foragers and brood. Some of these methods use unique equipment and most require additional boxes or split boards.

Split board …

But there are other ways to achieve the same overall goals, for example the Demaree method which keeps the entire workforce together by using a queen excluder and some well-timed colony manipulations.

confused.com

And then there are the 214 individual door opening/closing operations over a 3 week period (assuming the moon is at or near perigee) needed when you use a Snelgrove board {{10}}.

Like any recommendation to use brood and a half … my advice is ‘just say no’.

Just because Tim Toady …

… doesn’t mean you have to actually do things a different way each time.

The problem with asking a group – like your local association or the interwebs – a question is that you will get multiple answers. These can be contradictory, and hence confusing to the tyro beekeeper.

Far better to ask one person whose opinion you respect and trust.

Like your mentor.

You still may get multiple answers 😉 … but you will get fewer answers and they should be accompanied with additional justification or explanation of the pros and cons of the various solutions suggested.

This really helps understand which solution to apply.

Irrespective of the number of answers you receive I think some of the most important skills in beekeeping involve:

- understanding why a particular solution should work. This requires an understanding of the nitty gritty of the process. What are you trying to achieve by turning a hive 180° one week after a vertical split? Why should Apivar strips be repositioned half way through the treatment period?

- choosing one solution and get really good at using it. Understand the limitations of the method you’ve chosen. When does it work well? When is it unsuitable? What are the drawbacks?

This might will take some time.

More hives, less time

If you’ve only got one colony you’ll probably only get one chance per year to apply – and eventually master – a swarm control method.

With more colonies it is much easier to quickly acquire this practical understanding.

Then, once you have mastered a particular approach you can decide whether the limitations outweigh the advantages and consider alternatives if needed.

This should be an informed evolution of your beekeeping methods.

What you should not do is use a different method every year as – unless you have a lot of colonies – you never get sufficient experience to understand its foibles and the wrinkles needed to ensure the method works.

Informed evolution

If you consider the three beekeeping techniques I mentioned earlier – queen introduction, uniting colonies and swarm control – my chosen approach to two of them is broadly similar to when I started.

However, as indicated above, there are still lots of subtle variations that could be applied.

With both queen introduction and uniting colonies I’ve more or less standardised on one particular way of doing each of them. By standardising there’s less room for error … at least, that’s the theory. I now what I’m doing and I know what to expect.

In contrast, I’ve used a range of swarm control methods over the years. After a guesstimated 250+ ‘hive years’ I now almost exclusively {{11}} use one method that I’ve found to be extremely reliable and fits with the equipment and time I have available.

It’s not perfect but – like the methods I use for queen introduction and uniting colonies – it is absolutely dependable.

I think that’s the goal of learning one method well and only abandoning it when it’s clear there are better ways of achieving your goal. By using a method you understand and consider is absolutely dependable you will have confidence that it will work.

You also know when it will work by, and so can meaningfully plan what happens next in the season.

So, what are the variants of the methods I find absolutely dependable?

Queen introduction

99% of my adult queens – whether virgin or mated – are introduced in JzBz cages. I hang the queen (only, no attendants) in a capped JzBz cage in the hive for 24 hours and then check to see if the queenless (!) colony is acting aggressively to her.

If they are not I remove the cap and plug the neck of the cage with fondant. The bees soon eat through this and release the queen.

Checking for aggression

I used to add fondant when initially caging the queen but have had one or two queens get gummed up in the stuff (which absorbs moisture from the hive). I now prefer to add it after removing the cap. The queen needs somewhere ‘unreachable’ in the cage to hide if the colony are aggressive to her.

It’s very rare I use an alternative to this method. If I do it’s to use a Nicot pin on cage where I trap the queen over a frame of emerging brood {{12}}.

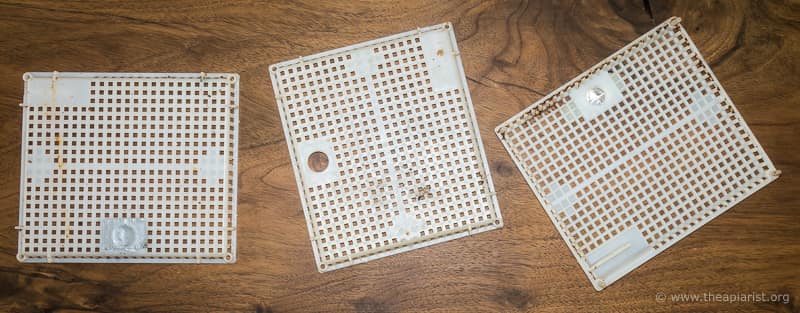

Nicot queen introduction cages

I use this method for real problem colonies … ones that have killed a queen introduced using the JzBz cage or that may contain laying workers.

Doing the latter is a pretty futile exercise at the best of times 🙁 .

Uniting colonies

Almost all colonies are united over newspaper. A sheet to two of an unstapled newspaper is easy to carry and uniting like this is almost always successful.

The brood box being moved goes on top. I want bees from the moved box to realise things have changed as they work their way down to the hive entrance. That way they’re more likely to not get lost when returning.

An Abelo/cedar hybrid hive … uniting colonies in midsummer

I don’t care whether the queen is in the upper or lower box and, if there’s any doubt that one of the colonies isn’t queenless, I use a queen excluder over the newspaper. I then check the boxes one week later for eggs.

At times I’ve used a can of air freshener and no newspaper. This has worked well, but it’s one more bulky thing to carry. I also prefer not to expose my bees to the chemical cocktail masquerading as Sea breeze, Summer meadow or Stale socks.

Since uniting doesn’t necessitate a timed return visit there’s little to be gained from seeking alternatives to newspaper in my view. Perhaps if I lived in a really windy location I’d have a different opinion … placing the newspaper over the brood box can be problematic in anything more than a moderate breeze {{13}}.

Swarm control

Like many (most?) beekeepers I started off using the classic Pagden’s artificial swarm. However, I quickly ran out of equipment as my colony numbers increased – you need two of everything including space on suitably located hive stands.

I switched to vertical splits. These are in essence a vertical Pagden’s artificial swarm, but require only one roof and stand. If you plan to merge the colonies again i.e. you don’t want to ’make increase’, vertical splits are very convenient. However, they can involve a lot of lifting if there are supers on the colony.

Vertical split – day 7 …

Now I almost exclusively use the nucleus method of swarm control. Used reactively (i.e. after queen cells are seen) it’s almost totally foolproof. Used proactively (i.e. before queen cells are produced) also works well. In both cases the timing of a return visit to reduce queen cells is important, and you need to use good judgement in deciding how strong to make the nuc.

Here’s one I prepared earlier

The nucleus method has a couple of disadvantages for my beekeeping. However, its ease of application and success rate more than make up for these shortfalls.

Tim Toady is ‘a good thing’ …

I love the flexibility of perl for programming. I can write one-liners to do a quick and dirty file conversion. Alternatively I can craft hundreds of lines of well-documented code that is readable, easy to maintain and robust.

Others, in the very best tradition of Tim Toady, might write programs to do exactly the same things but in a completely different way.

The flexibility to tackle a task – the three used above for example, or miticide treatment, queen rearing, uncapping frames or any of the hundreds of individual tasks involved in beekeeping – in different ways provides opportunities to choose an approach that fits with your diary, manual dexterity, available equipment, preferences, ethics or environment.

In this regard it’s ‘a good thing’.

Choice and flexibility are beneficial. They make things interesting and, for the observant beekeeper, they provide ample new opportunities for learning.

… and a distraction

However, this flexibility can also be a distraction, particularly for beginners.

That is why I emphasised the need to learn the intricacies of the method you choose by understanding the underlying mechanism, and the subtleties needed to get it to work absolutely dependably.

Don’t just try something once and then do something totally different the next year {{14}}. Use the method for several years running (assuming it’s an annual event in the beekeeping calendar), or at least on a lot of different colonies.

Choose a widely used and well-documented method in the first place {{15}}. Read about it, understand it and apply it. Tweak it until it either works exactly as you want it to i.e. reliably, efficiently, quickly or whatever, or choose a different widely used and well-documented method and start over again.

Get really competent at the methods you choose.

Once your beekeeping is built upon a range of absolutely dependable methods you have the foundations to be a little bit more expansive.

You can then indulge yourself.

Explore the options offered by Tim Toady.

Things might fail, but you always have a fallback that you know works.

Note

The Apiarist is moving to an upgraded server in the next few days, If the site is temporarily offline then I’ve either pressed the wrong button, or the site will be back in a few minutes … please try again 😉

{{1}}: It is still a painful memory.

{{2}}: Now, as a crushingly boring senior academic I generously dole out these mundane tasks to others.

{{3}}: Running Unix/Linux or OS X …

{{4}}: The name is also a biblical reference to the ’pearl of great price’ in Matthew 13:46 … Larry Wall, the inventor of perl, is a linguist and Christian.

{{5}}: Well, they are, but not exclusively.

{{6}}: In one or two cases, seemingly the Planet Zog.

{{7}}: Writes The Apiarist from 56°40’N, 5°50’W, Zone 9b.

{{8}}: That at least should be obvious …

{{9}}: Delete options from the left to reflect how precious your colony is and/or your risk tolerance.

{{10}}: For those unfamiliar with a Snelgrove board it’s a clever way to confuse the bees into not swarming.

{{11}}: Almost because I’ve done one “can’t find the queen split” in the last 3 years.

{{12}}: The 99% above is a guess, but I’ve not used this alternative for at least 5 years.

{{13}}: Drawing pins help.

{{14}}: Unless it was an abject failure I suppose.

{{15}}: Building a Taranov board isn’t the most obvious way to get really good at swarm control.

Join the discussion ...