The winter cluster

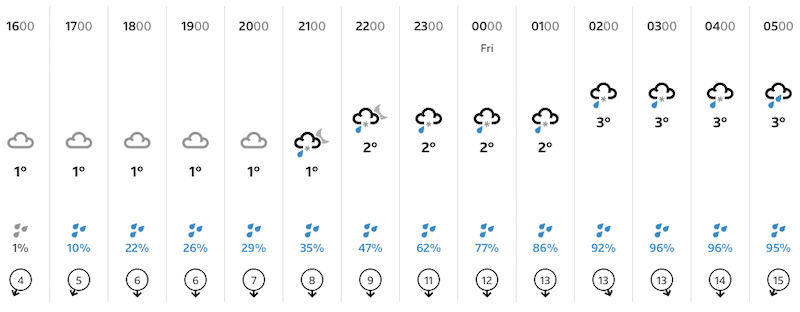

We had our first snow of the year last night and the temperature hasn’t climbed above 3°C all day. The hills look lovely and, unsurprisingly, I’ve not seen a single bee venturing out of the hives.

If you crouch down close to the hive entrance and listen very carefully you’ll be able to hear …

… absolutely nothing.

Oh no! Are they still alive? Maybe the cold has killed them already?

If you rap your knuckles against the sidewall of the brood chamber you’ll hear a brief agitated buzz that will quickly die back down to silence.

Don’t do that 😯

Don’t disturb them unless you absolutely have to. They’re very busy in there, huddling together, clustering to maintain a very carefully regulated temperature.

Bees and degrees

Any bee that did venture forth at 3°C would get chilled very rapidly. Although the wing muscles generate a lot of heat (see below), this uses a large amount of energy.

If the body temperature of an individual bee dips below ~5.5°C they become semi-comatose. They lose the ability to move, or warm themselves up again. Below -2°C the tissues and haemolymph starts to freeze.

However, as long as they’re not exposed to prolonged chilling (more than 1 hour) they can recover if the environmental temperature increases {{1}}.

An individual bee has a large surface area to volume ratio, so rapidly loses heat. Their hairy little bodies help, but it’s no match for prolonged exposure to a cold environment.

But the bees in your hives are not individuals. Now, perhaps more than any other time in the season, they function as a colony. Survival, even for a few minutes at these temperatures, is dependent upon the insulation and thermoregulation provided by the cluster.

All for one, one for all

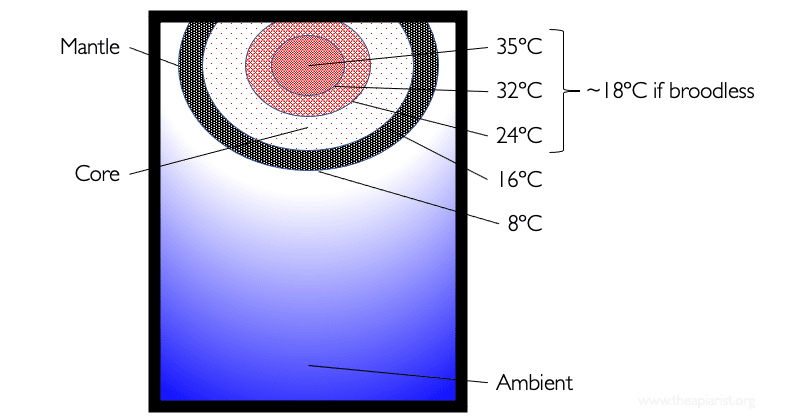

The temperature in the clustered colony is always above the coma-inducing 5.5°C threshold, even for the bees that form the outer surface layer, which is termed the mantle.

And the temperature in the core of the cluster is much warmer still, and if they’re rearing brood (as they soon will be {{2}}) is maintained very accurately.

The mantle

The temperature inside the hive entrance, some distance from the cluster, is the same as the external ambient temperature. On a cold winter night that might be -5°C (in Fife), or -35°C (in Manitoba).

Studies have shown that clustered colonies can survive -80°C for 12 hours, so just a few degrees below freezing is almost balmy.

Due to thermal radiation from the clustered colony, the temperature of the airspace around the colony increases as you get nearer the cluster. Draught free hives – and beekeepers that refrain from rapping on the brood box sidewall – will reduce movement of this air, so reducing thermal losses from convection.

The clustered colony is not a uniform ‘ball’ of bees. It has two distinct layers. The outer layer is termed the mantle and is very tightly packed with bees facing inwards. These bees are packed in so tightly that their hairy bodies trap air between them, effectively forming an insulating quilt.

To reduce heat loss further these mantle bees have a countercurrent heat exchanger (between the abdomen and the thorax) that reduces heat loss from the haemolymph circulating through their projecting abdomens.

The mantle temperature is maintained no lower than about 8°C, safely above coma-inducing lower temperatures.

Penguins and flight muscles

I’ve seen it suggested that the mantle bees circulate back into the centre of the cluster to warm up again, but have been unable to find published evidence supporting this. It’s an attractive idea, and it’s exactly what penguins do on the Antarctic ice sheet … but that doesn’t mean it’s what bees do.

Penguins, not bees

Although bees can cope with temperatures of 8°C, they cannot survive this temperature for extended periods. If bees are chilled to below 10°C for 48 hours they usually die. This would support periodically recirculating into the centre of the cluster to warm up.

Bees do have the ability to warm themselves by isometric flexing of their flight muscles. Essentially they flex the opposing muscles that raise and lower the wings, without actually moving the wings at all.

This generates a substantial amount of heat. On a cool day, bees warm their flight muscles by this isometric flexing before leaving on foraging flights. They have to do this as the flight muscles must reach 27°C to generate the wing frequency to actually achieve flight. Since bees will happily forage above ~10°C this demonstrates that the isometric wing flexing can raise the thoracic flight muscle temperature by at least 15-17°C.

But, briefly back to the penguin-like behaviour of bees, neuronal activity is reduced at lower temperatures. In fact, at temperatures below 18°C bees don’t have sufficient neuronal activity to activate the flight muscles for heat generation. This again suggests there is a periodic recycling of bees from the mantle to the centre of the cluster.

How can bees fly on cool days if it’s below this 18°C threshold? The day might be cooler, but the bee isn’t. The colony temperatures are high enough to allow sufficient neuronal activity for the foragers to pre-warm their flight muscles to forage on cool days.

Anyway, enough of a digression about flight muscles, onward and inward.

The core

Inside the mantle is the core. This is less densely occupied by bees, meaning that they have space to move around for essential activities such as brood rearing or feeding.

The temperature of the core varies according to whether the colony is rearing brood or not. If the colony is broodless the core temperature is maintained around 18°C.

The tightly packed mantle bees reduce airflow to the core. As a consequence of this the CO2 levels rise and the O2 levels fall, to about 5% and 15% respectively (from 0.04% CO2 and 21% O2 in air). A consequence of this is that the metabolic rate of bees in the core is decreased, so reducing food consumption and minimising the heat losses from respiration.

Brood rearing

My clustered winter colonies are probably just thinking about starting to rear brood {{3}}.

Bees cannot rear brood at 18°C. Brood rearing is very temperature sensitive and occurs optimally at 34.5-35.5°C.

Outside that narrow temperature band things start to go a bit haywire.

Pupae reared at 32°C emerge looking normal (albeit a day or so later than the expected 21 days for a worker bee), but show aberrant behaviour. For example, they perform the waggle dance less enthusiastically and less accurately {{4}}. In comparison to bees reared at 35°C, the ‘cool’ bees performed only 20% of the circuits and the ‘waggle run’ component was a less accurate predictor of distance to the food source.

Neurological examination of bees reared at 35°C showed they had increased neuronal connections to the mushroom bodies in the brain, when compared with those reared as little as 1°C warmer or cooler. This, and the behavioural consequences, shows how critical the brood nest temperature is.

The cluster position

The cartoon above shows the cluster located centrally in the hive. This isn’t unusual, though the cluster does tend to move about within the volume available as they utilise the stores.

You can readily determine the location of the cluster. Either insert a Varroa tray underneath an open mesh floor for a few days …

… or by using a perspex crownboard. I have these on many of my colonies and it’s a convenient way of determining the size and location of the cluster with minimal disturbance to the colony.

Though you don’t need to check on them like this at all.

The photograph above was from late November (6 years ago). The brood box is cedar and therefore provides relatively poor insulation.

While checking the post-treatment Varroa drop in my colonies this winter it was obvious that cluster position varied significantly between cedar and poly hive types.

In poly hives (all my poly hives are either Abelo or Swienty) it wasn’t unusual to find the cluster tight up against one of the exterior side walls. In contrast, colonies hived in cedar brood boxes tended to be much more central.

This must be due to the better insulation of polystyrene compared with cedar.

Insulation

Although I don’t think I’ve noticed this previously in the winter, it’s not uncommon in summer to find a colony in a poly hive rearing brood on the outer side of the frames adjacent to the hive wall. This is relatively rare in cedar boxes, other than perhaps at the peak of the summer.

If you’re interested in hive insulation, colony clustering and humidity I can recommend trying to read this paper by Derek Mitchell.

I don’t provide additional insulation to my colonies in the winter. It’s worth noting that all my hives have open mesh floors. In addition, the crownboard is topped by a 5 cm thick block of insulation throughout the year, either integrated into the crownboard or just stacked on top.

If you use perspex crownboards you must have insulation immediately above them. If you don’t you get significant amounts of condensation forming on the underside which then drips down onto the cluster.

The winter cluster and miticide treatment

The only time you’re likely to see the winter cluster is when treating with an oxalic acid-containing miticide. And only then when trickle treating.

With the choice between vaporising or trickle treating, I tend to be influenced by the ambient temperature.

If the cluster is very tightly clustered (because it’s cold) I tend to trickle treat.

If it is more loosely clustered I’m more likely to vaporise.

The threshold temperature is probably about 8°C, but I’m not precious about this. The logic – what little is applied – is that the oxalic acid crystals permeate the open cluster better than they would a closed cluster.

I’ve got zero evidence that this actually happens 😉

However, it’s worth reiterating the point I made earlier about airflow through the mantle. Since this is restricted in a tightly clustered colony – evidenced by the reduced O2 and elevated CO2 levels – then it seems reasonable to think that OA crystals are less likely to penetrate it either.

Of course, there’s an assumption that the trickled treatment can penetrate the cluster, and doesn’t just coat the mantle bees with a sticky OA solution.

Which neatly brings us back to penguins … if these mantle bees do recirculate through the cluster core they’ll take some of the OA with them, even if it didn’t get there directly.

Finally, it’s worth noting that cluster formation starts at about 14°C. As the temperature drops the cluster packs together more tightly. Between 14°C and -10°C the volume of the cluster reduces by five-fold.

By my calculations {{5}}, at 2°C and 8°C the cluster is three and four times it’s minimal volume respectively, so perhaps both OA vapour and trickled solution could permeate perfectly well.

{{1}}: We take advantage of this in the lab and chill bees briefly on ice to anaesthetise them for certain things. Soon after you return them to the incubator they become fully active again.

{{2}}: Here at least …

{{3}}: Actually, they’re not thinking about it at all. That’s me being anthropomorphic. They’ve been broodless for the last 4-5 weeks and I fully expect them to have capped brood shortly after the winter solstice. So, although they’re not thinking about it, it’s going to happen anyway. Isn’t evolution a wonderful thing?

{{4}}: Note to self … I really should write something about the waggle dance … the only bee-related Nobel Prize deserves a post of its own.

{{5}}: Of the back of an envelope type which assume there’s a linear relationship between cluster size and the ambient temperature.

Join the discussion ...