The waggle dance

Ask a non-beekeeper what they know about bees and you’ll probably get answers that involve honey or stings.

Press them a little bit more about what they know about other than honey and stings and some will mention the ‘waggle dance’.

That the waggle dance is such a well-known feature of honey bee biology is probably explained by two (related) things; it involves a relatively complex form of communication in a non-human animal, and because Karl von Frisch – the scientist who decoded the waggle dance – received the Nobel Prize {{1}} for his studies in 1973.

Von Frisch did not discover the waggle dance. Nicholas Unhoch described the dance at least a century before Von Frisch decoded the movement, and Ernst Spitzner – 35 years earlier still – observed dancing bees and suggested they were communicating odours of food resources available in the environment.

Inevitably, Aristotle also made a contribution. He described flower constancy {{2}} and suggested that foragers could communicate this to other bees.

Language and communication are important. The development of language in early humans almost certainly contributed to the evolution of our culture, society and technology. Communication in non-human animals, from the chirping of grasshoppers to the singing of whales, is of interest to scientists and non-scientists alike.

It is therefore unsurprising that the ‘dance language’ of honey bees is also of great interest. Although not a ‘language’ in the true sense of the word, Von Frisch described the symbolic language of bees as “the most astounding example of non-primate communication that we know” over 50 years ago. This still applies.

The waggle dance

The waggle dance usually takes place in the dark on the vertical face of a comb in the brood nest, usually close to the nest entrance. The dance is performed by a successful forager i.e. one that has located a good source of pollen, nectar or water, and provides information on the presence, the quality, identity, direction and distance of the source, so enabling nest-mates to find and exploit it.

The dance consists of two phases:

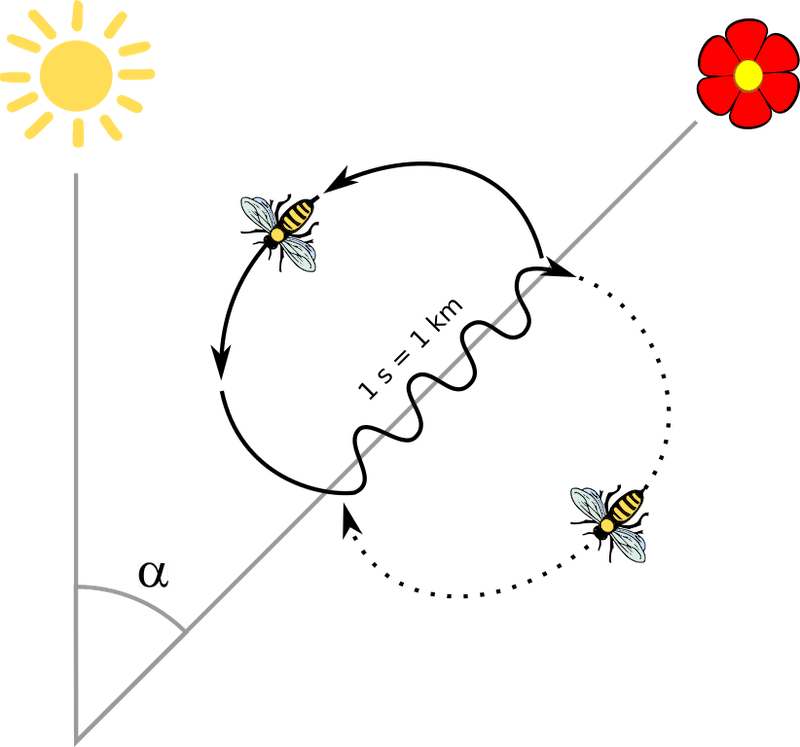

- The figure of eight-shaped ‘return phase’ in which the bee circles back, alternately clockwise and anticlockwise, to the start of …

- The ‘waggle phase’, which is a short linear run in which the dancer vigorously waggles her abdomen from side to side.

The direction of the food source is indicated by the angle of the waggle phase from gravity i.e. a vertical line down the face of the comb. This angle (α in the figure below) indicates the bearing from the direction of the sun that needs to be followed to reach the food source.

For example, if the dancer performs a waggle phase vertically down the face of the comb, the food source must be opposite the current position of the sun.

The distance information is conveyed by the duration of the waggle phase. The longer this run is, the more distant the source. A run of 1 second duration indicates the food source is about 1 kilometre away.

The quality of the food source is indicated by the vigour of the waggling during the waggle phase and the speed with which the return phase is conducted.

Surely it can’t be that simple?

Yes, it can.

What I’ve described above allows you to interpret the waggle dance sufficiently well to know where your bees are foraging.

Next time you lift a frame from a hive and see a dancing bee, circling around in a little cleared ‘dance floor’ surrounded by a group of attentive workers, try and decode the dance.

Remember that the dance is performed with relation to gravity in the darkened hive. You’re looking to identify the angle from a vertical line up the face of the brood comb to determine the direction from the sun.

Time a few waggle phases (one elephant, two elephants etc.) and you’ll know how far away the food source is.

Really, it’s that simple?

Of course not 😉

The waggle dance was decoded more than half a century ago and remains an active subject for researchers interested in animal communication.

What you’ll miss in your observations is an indication of the type of nectar or pollen resource that the dancing bee is communicating. The dancing worker carries the odour of the food source and may also regurgitate nectar, presumably helping those ‘watching’ (remember, it’s dark … nothing to see here!) determine the type of resource to look for when they leave the hive.

You will also be unable to detect the pulsed thoracic vibrations that the dancing bee produces. These are also indicators of the quality of the food source; better (e.g. higher sucrose content) resources elicit increased pulse duration, velocity amplitude and duty cycle, though the number of pulses is related to the duration of the waggle phase, and so is another potential indicator of distance.

Inevitably, there are also pheromones involved.

There always are 😉

The dancing bee produces two alkanes, tricosane and pentacosane, and two alkenes, Z-(9)-tricosene and Z-(9)-pentacosene. These appear to stimulate foraging activity {{3}}.

But it’s cloudy … or rain stops play … or nighttime

What happens to dancing bees if foraging is interrupted, for example by poor weather or night?

The dancing bee continues to change the angle of the waggle phase as the sun moves across the sky. This means that a dancing bee will correctly signal the direction to the food source, even if they have not left the hive for several hours.

During their initial orientation flights they learn the sun’s azimuth as a function of the time of day, and use this to compensate for the sun’s time-dependent movement.

Some bees even dance during the night, in which case the watching workers must presumably make their own compensations for the time that has elapsed since the dance {{4}}.

And what happens if the sun is obscured … by clouds, or buildings or dense woodland? How can those directions be followed?

Under these circumstances the foraging bee detects the position of the sun by the pattern of polarised light in the sky.

Scout bees

The waggle dance is also performed by scout bees on the surface of a bivouacked swarm. In this instance it is used to communicate the quality, direction and distance of a new potential nest site.

The intended audience in this instance are other scout bees, rather than the general forager population {{5}}. These scouts use a quorum decision making process to determine the ‘best’ nest site in the area to which the bivouacked swarm eventually relocates.

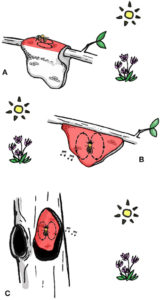

The shape of the bivouac often lacks a true vertical surface. However, since it’s in the open the dancing bees can orientate the waggle run directly with relation to the sun’s direction, rather than to gravity.

Under experimental conditions the dancing bee can communicate the presence and quality of a food source on a horizontal comb, but – with no reference to gravity – all directional information is lost {{6}}.

The round dance

The duration of the waggle phase is related to the distance from the nest to the food source. Therefore the recognisable waggle dance tends to get difficult to interpret for sources very close to the nest.

It used to be thought that there was a distinct directionless dance (the ’round dance’) for these nearby i.e. 10-40 metres, food sources. However, more recent study {{7}} suggests that dancers were able to convey both distance and direction information irrespective of the separation of nest and food source. This indicates that bees have just one type of dance for forager recruitment, the waggle dance.

Do all bees communicate using a waggle dance?

There are a very large number of bee species. In the UK alone there are 270 species, 250 of which are solitary.

There’s a clue.

Solitary bees are like me at a disco … they have no one to dance with 🙁

I’ll cut to the chase to help you erase that vision.

The only bees that use the waggle dance are honey bees. These all belong to the genus Apis.

They include our honey bee, the western honey bee (Apis mellifera), together with a further seven species:

- Black dwarf honey bee (Apis andreniformis)

- Red dwarf honey bee (Apis florea)

- Giant honey bee (Apis dorsata)

- Himalayan giant honey bee (Apis laboriosa)

- Eastern honey bee (Apis cerana)

- Koschevnikov’s honey bee (Apis koschevnikovi)

- Philippine honey bee (Apis nigrocincta)

Dwarf honey bees nest in the open on a branch and dance on the horizontal surface of the nest. The waggle run is orientated ‘towards’ the food source. Apis dorsata is also an open-nesting bee, but forms large vertically-hanging combs. It dances relative to gravity, and indicates the direction by the angle of the waggle run in the same way that A. mellifera does.

The cavity nesting bees, A. cerana, A. mellifera, A. koschevnikovi, and A. nigrocinta produce the most developed form of the dance.

The dances of A. mellifera and A. cerana are sufficiently similar that they can follow and decode the dance of the other.

The complexity of the nest site and the waggle dance reflects the evolution of these bee species. The earliest to evolve (i.e. the most primitive), A. andreniformis and florea, have the simplest nests and the most basic waggle dance. In contrast, the cavity nesting species evolved most recently, form the most complex brood nests and have the most derived waggle dance.

When and why did the waggle dance evolve?

Assuming that the waggle dance did not independently evolve (there’s no evidence it did, and ample evidence due to its similarity between species that it evolved only once) it must have first appeared at least 20 million years ago, when extant honey bee species diverged during the early Miocene.

The ‘why’ it evolved is a bit more difficult to address.

Behavioural changes often arise in response to the environment in which a species evolves.

Bipedalism in non-human primates (like the australopithecines) is hypothesised to have evolved in part due to a reduction in forest cover and the increase in savannah. Apes had to walk further between clumps of trees and bipedalism offered greater travel efficiency.

Perhaps the waggle dance evolved to exploit a particular type or distribution of food reserves?

In this regard it is interesting that the ‘benefit’ of waggle dance communication varies through the season.

If you turn a hive on its side the combs are horizontal {{8}}. Under these conditions the dancing bees can communicate the presence and quality of a food source. However, they cannot communicate its location (either direction or distance).

In landmark studies Sherman and Visscher {{9}} showed that, at certain periods during the season, the absence of this positional information did not affect the weight gain by the hive i.e. the foraging efficiency of the colony.

They concluded that during these periods forage must be sufficiently abundant that simply stimulating foraging was sufficient. Remember those alkanes and alkenes produced by dancing bees that do exactly that?

Tropical habitats

This observation, and some elegant experimental and modelling studies, suggest that dancing is beneficial when food resources are:

- sparsely distributed – therefore difficult (and energetically unfavourable) to find by individual scouting

- clustered or short-lived resources – when it’s gone, it’s gone

- distributed with high species richness – if there’s a huge range of flowers, which are the most energetically rewarding (sugar-rich) to collect nectar from?

One of the experimental studies that contributed to these conclusions (though there’s still controversy in this area) was the demonstration that waggle dancing was beneficial in a tropical habitat, but not in two temperate habitats. This makes sense, as food resources have different spatiotemporal distribution in these habitats. Tropical habitats are characterised by clustered and short-lived resources.

Therefore the suggestion is that the waggle dance of Apis species evolved, presumable early in the speciation of the genus, in a tropical region where food resources were patchily distributed, available for only limited period and present alongside a wide variety of other (less good) choices.

For example, like individual trees flowering in a forest …

Finally, it’s worth noting that there is evidence that bees that dance are able to successfully exploit food resources further away than would otherwise be expected from their body size.

This also makes sense.

It’s much less risky flying off over the horizon if you know there’s something to collect once you get there {{10}}.

Notes

If you arrived here from my Twitter feed (@The_Apiarist) you’ll have seen the tweet started with the words “Dance like nobody’s watching”, words that are often attributed to Mark Twain.

The full quote is something like “Dance like nobody’s watching; love like you’ve never been hurt. Sing like nobody’s listening; live like it’s heaven on earth”.

Pretty sound advice.

But it’s not by Mark Twain. It’s actually from a country music song by Susanna Clark and Richard Leigh. This was first released on the Don Williams album Traces in 1987. So only about 90 years out 😉

{{1}}: Equally shared with Nikolaas Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz, for “their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behaviour patterns”.

{{2}}: The tendency for a bee to visit a single type of flower, ignoring others in the same environment.

{{3}}: Thom et al., 2007 The scent of the waggle dance. PLoS Biology 5:e228.

{{4}}: I’m not sure if this is formally proven … it might be that the watching workers ignore anything but the most recently ‘watched’ dance.

{{5}}: How do regular foragers know not to ‘watch’ the dance?

{{6}}: This always makes me wonder whether the bees we see dancing on a frame removed from the hive are doing so with relation to the position of the comb in the hive, or the position of the sun when on a frame in our hands. Someone must surely know this? Whatever, it should be easy to test. Next time I find a dancing bee on a frame I’ll rotate the frame through 90° and see if the direction of the waggle run changes.

{{7}}: See Gardner et al., (2008) Do honeybees have two discrete dances to advertise food sources? Animal Behaviour 75:1291-1300.

{{8}}: Formally on two of the four sides, of course.

{{9}}: Sherman & Visscher (2002) Honeybee colonies achieve fitness through dancing. Nature 419:920–922.

{{10}}: And this is a good point to stop. It’s worth noting that waggle dancing has been decoded to map food resources up to 11 km distant … that potentially involves an 11 second waggle run, which I’ll discuss in a separately when I revisit my ageing sphere of influence post.

Join the discussion ...