The summer honey harvest

This post was originally titled "Don't do this at home" but I finally opted for something a little more informative in the hope of boosting my feeble advertising income from Google 'hits'.

In Fife the summer honey is usually ready in early/mid-August. By 'ready' I mean the the bees have capped the majority of the stores in the super frames, and the uncapped honey passes the 'shake test' indicating that the water content is low enough that the honey will not ferment.

My bees are a long way from any of the late season sources of nectar e.g. balsam, and it's far too soon for the ivy. Mid-August is therefore a natural break in forage availability, and a logical time to take the honey off and start preparing the colonies for winter.

The honey harvest is a busy time and involves lots of work; clearing the supers, feeding and treating the bees, transporting the heavy supers to wherever you do the extraction, holding on - during run after run after run - to an erratically wobbling extractor and then (as time-consuming as all the rest put together) cleaning up afterwards.

All of which means that the very last thing you would want to be doing simultaneously is moving house.

Which, of course, is what I did 😱.

At the time it seemed like a good idea ... I'd have a van to transport all the supers together, the house was largely empty, so I'd have space to work and could do so late into the evening, and I'd be doing lots of heavy lifting anyway, so a few more boxes and buckets would hardly be noticed.

Ha!

Queenlessness does not mean honeylessness

Any regular readers will be aware that it's been a slightly odd season. The weather has been consistently poor, queen mating was problematic at best (and catastrophic at worst) and swarming behaviour has been unpredictable and a little uncontrollable.

Despite this - or perhaps because of this - colonies built up well in the Spring, generated an average honey crop in early June and then settled in for the long, hot 'summer'.

Since I knew I was moving I merged a lot of colonies in June, leaving me with just 9 for the summer honey. Some were successfully requeened - either with queens raised in hive or mated queens I had reared - but about a third have the same queen they started the season with.

Several boxes had been queenless, or had at least lacked a laying queen, for a prolonged period in late June and July. With no queen and/or little or no brood to rear, the bees seem to busy themselves filling the supers rather than moping about the hive feeling sorry for themselves.

Whatever the real (non-anthropomorphic) reason, there were plenty of supers, and they'd appeared reassuringly heavy in the first week of August when I'd last checked.

Supers off, Apivar in, fondant on

Inevitably it was raining, albeit gently, when I arrived in the apiary to add the clearers.

The rain wasn't an issue, I was not going to open any of the brood boxes (that was tomorrow), but the weight of the supers combined with the greasy/muddy conditions underfoot were. However, by not attempting to lift three supers together {{1}}, I managed to avoid any Buster Keaton-like comedic events.

There were a total of 30 supers on the 9 hives in the two apiaries (3 in one and 6 in the other) to be cleared.

In addition, there were also a couple of brood boxes I'd used as supers, either inadvertently (by leaving the super above a queen excluder after uniting two colonies and then compressing the brood nest down into one box) or deliberately, having run out of supers. I don't extract from brood frames but cleared these anyway {{2}}.

Supers

The following morning I collected the supers and stacked them in the van. The clearers I use are very effective except when a colony is queenless.

I cannot claim that any clearer is ineffective on queenless colonies, because these are the only clearers I use, but wouldn't be surprised.

One colony appeared to be queenless. There were bees in the supers, a charged queen cell on the bottom edge of one of the super frames (yes, bees do move eggs ... but was this a worker-laid egg?) and no sign of a queen in the brood box.

In all honesty I didn't take a long time searching for her. The colony wasn't very strong and there was little chance of getting a new queen mated and laying for it to build up strongly for winter.

I therefore shook the bees off the super frames and the brood frames. With a day of good weather ahead (for a change) they would redistribute themselves to the flanking colonies.

30-odd full supers weigh a lot. I'd been concerned about them shifting about in the van during the journey back to the West coast (25 miles were on wiggly single-track roads). Fortunately, four supers were exactly the width of a Peugout Boxer van (which was exactly the width of the single-track road), so I stacked them behind the bulkhead, held in place with some chipboard shelves and a couple of ratchet straps.

In practice, their weight combined with the propolis, meant that nothing moved at all 😄.

Apivar

With the supers cleared and off it was time to add the Apivar strips. In Scotland this is my favoured late-summer miticide. It is a temperature-independent, fit and don't forget, highly effective miticide.

"Don't forget", as you must remember to reposition the strips in a few weeks, and remove them after 8-10 weeks.

The strips were placed either side of the brood nest.

Don't just guess where this is ... look for the outer frame of brood, which is usually adjacent to a pollen-filled frame, and place the strips there, at opposite 'corners' of the brood nest.

In some hives this meant the strips were just five frames apart, in other 9 or more.

The brood nest and resulting hive population are contracting quite fast, and the bees being reared now are almost certainly the diutinus (long-lived) winter bees that will remain present in the colony until the early months of 2025. It is critical that they are reared in a colony with low levels of mites, explaining why rational Varroa control involves late summer (rather than mid or late autumn) miticide treatment.

As an aside, several correspondents have commented on experiencing high mite levels this season. Perhaps I've been lucky, or the weather has restricted colony size (or my queenless colonies experienced prolonged brood breaks), but I've not seen a mite, or a bee with DWV symptoms, this season.

Fondant

With no strong nectar flow and no honey, other than a bit sequestered in the brood box, it's necessary to feed the colonies if they are to survive the winter.

I only feed fondant at this time of the year. I've written extensively about this previously, so won't repeat myself.

Each colony was given a 12.5 kg block, split lengthways and opened 'face down' (like a mistreated book) over a queen excluder (QE). I only leave the QE in place to make lifting the fondant to reposition the Apivar strips a bit easier. Without the QE the fondant becomes fused to the top bars of the frames, and it's a bit of a nightmare - for the beekeeper and the bees - to access the brood box.

In reality, the bees will probably have finished the fondant before the Apivar strips need repositioning, but it's just easier to do it this way. Light colonies will also need an additional half block of fondant in a few weeks, and I remove any uneaten fondant {{3}} which (I suspect) acts as a heatsink above the winter cluster, and certainly means there will be a space above the colony which I want to avoid.

Before anyone asks, yes the bees take the fondant down and store it in the brood box.

The drive west was uneventful and tediously slow, but I didn't arrive so late that there wasn't time to empty the supers and stack half of them on top of my (lidless) honey warming cabinet to warm them and so make extracting easier.

Extraction

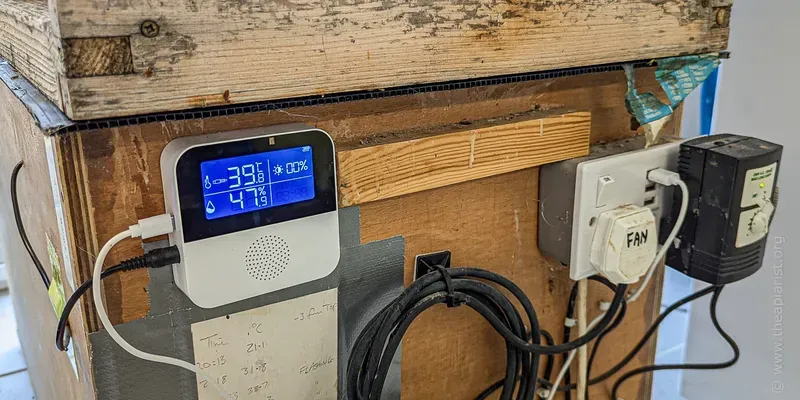

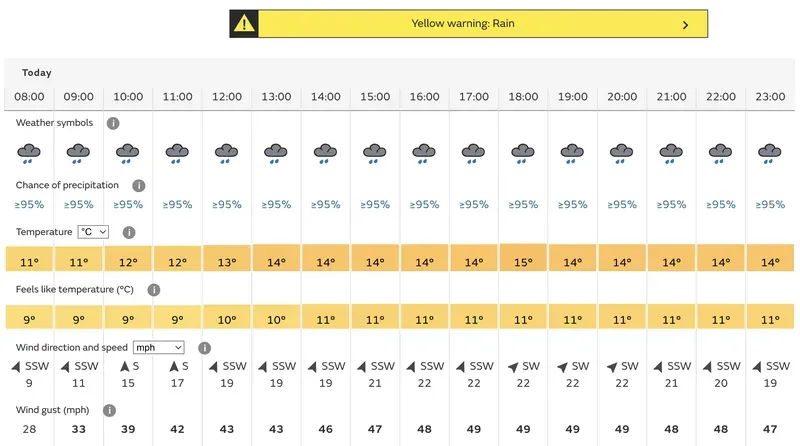

The following day dawned miserable and wet ... a perfect day for extracting.

Extraction is a bittersweet experience.

There's the excitement of the first run, with the sparkling golden honey running out of the tap, through the filter and into the bucket.

It's a magical sight and one that I always enjoy.

Then there's the crushing tedium of going through the same uncap, load, balance, run, reverse, unload, change the bucket process for hours as the pile of full supers dwindles and the stack of full buckets increases.

But it was nearly a bittersweet experience that didn't happen at all.

I prepared the room, unpacked the extractor, checked I had everything I needed and selected an upbeat playlist to work to {{4}}.

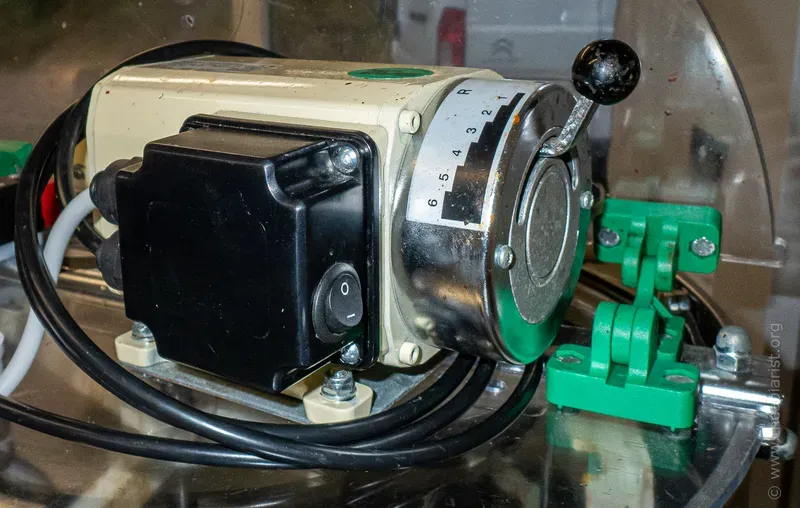

But the extractor would not start.

I changed the fuse ... nada.

I checked the mains supply to the socket ... nope.

I gnashed my teeth and cursed a bit ... and then vaguely remembered having the same problem a decade or so ago, the cause of which was a push-fit spade connector in the 'control box' that had worked loose.

The connector is located in the black control box, the cover of which is held in place with short stainless steel bolts requiring a 2 mm allen key.

And this was where the problems started. All of my allen keys were 250 miles away in the Scottish Borders 😢. I asked my immediate neighbour who rummaged around and found a big collection of allen keys, every one of which was Imperial (not metric), and none of which fitted. I eventually sourced a 2 mm allen key from a friend 'down the road', necessitating another hour in the (thankfully empty) van.

The spade connector had worked loose and the allen key allowed me to access it and fix it.

Off we go!

Wobbling repetition

It's the repetition during extraction that grinds you down. One or two supers are fine, but by ten times that the novelty has well and truly worn off.

I cannot imagine the tedium of doing this sort of thing on a commercial scale, though of course the beefarmers have the benefit of a bit more automation.

It took me an afternoon, evening and the following morning to get through all 30 supers. By then my left hand was calloused and encrusted with propolis, I was partially deaf from the extractor and the - of necessity amplified - backing music {{5}}, and I'd been reminded of most of the little tricks that make the process easier, but that I'll forget before doing it all again next year.

Unbalanced

Inevitably, the frames will contain different amounts of honey. You can spend ages carefully guesstimating their weight, distributing them evenly in the extractor cage and correcting your errors once the extractor starts excitedly wobbling across the room.

However, it's easier to get into a routine that gets it mostly balanced, and then gently increase the speed of the extractor.

My extractor takes 9 frames and my supers - quell surprise - usually contain the same number {{6}}. This is not a coincidence. Some supers are packed full, in others the middle frames tend to be heavier than the outliers (the bees generally fill those in the middle first, in the warm 'chimney' above the brood nest). I take the heaviest frames and distribute these evenly around the cage - for example, in positions 2, 5 and 8. I then add the lighter frames flanking these heavier ones.

I always try and keep frames of broadly similar weights separated by two other frames i.e. at positions 1, 4 and 7 or, you get the idea.

Since all the frames have been pre-warmed (above the honey warming cabinet) a gentle start to the extractor quickly spins out some of the honey from the heaviest frames. Consequently, the weights become more balanced, meaning the speed can then be increased.

Gradually I ramp the speed up until it is (relatively) smoothly going 'eyeballs out' then, after a few minutes, I bring it to a standstill then run it in reverse for a few minutes.

How many minutes?

Once full speed is reached it's a law of diminishing returns ... you could spin for an hour and extract little more than you get in the first 10 minutes. At some point, the viscosity of the honey and the limited centrifugal force being applied are balanced {{7}}, and you might as well start another lot of frames.

I use a torch and look down at the inner sidewall of the spinning extractor. Bright sparkles appear when droplets of honey hit the sidewall. Once these are few and far between (or very, very small) I stop the spin.

With pre-warmed supers, a reasonably well-balanced extractor and quite a bit of impatience, I find 4-5 minutes in each direction at full speed is sufficient.

It's the little things

With all that repetition, there's ample time to notice individual features of some of the frames being handled ... the frame with a queen cup in a little central hollow that appeared a few years ago, the ages of some of the frames ...

... with the earliest I remember seeing this year being dated 2009, and the absence of a 2011 frame stopping me from getting a straight flush in the super shown above.

I also found this foundationless frame from 2014. This has fishing line to provide structural support and will have been used twice a year for the last decade, emphasising how robust these are once they are fully drawn.

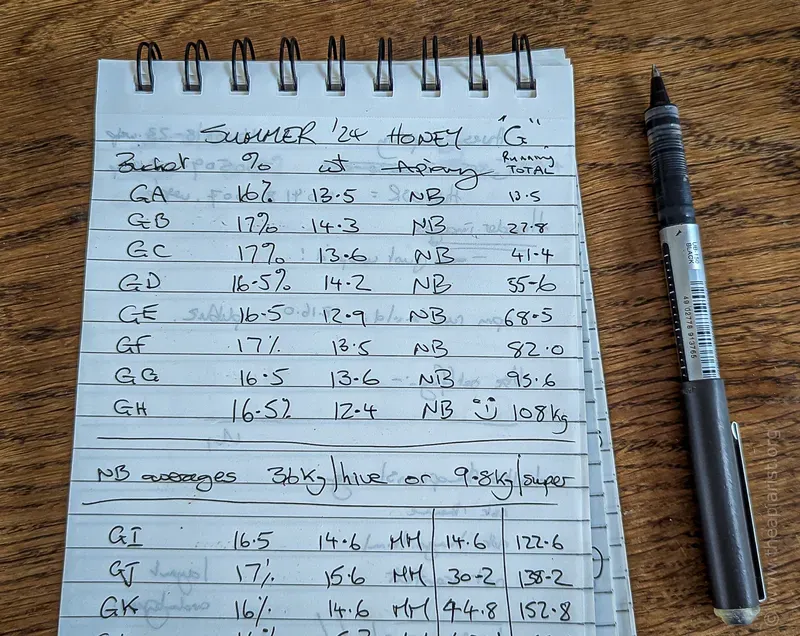

Scores on the doors

It was a good summer for honey. Despite all my whinging and whining about lousy weather, the bees have been busy and - even with fewer hives than normal - they did very well overall.

Overall I ended up with a bit over 280 kg from 9 colonies, so averaging ~31 kg per hive or ~9.3 kg/super. For my part of Scotland that's pretty reasonable, and I'm more than happy with how the season turned out.

Any more than that and jarring the honey would become as tedious as extracting it. 280 kg is about 800 jars, so you'll be reading lots about the drudgery of jarring honey over the next few months 😉.

Every bucket of honey gets a code number indicating the harvest e.g. GA, GB, GC ... GT is this summer, and has the weight and water content written on the lid (and in the spreadsheet). I can therefore use the buckets with the highest water content first, reducing the risk of the stored honey fermenting.

I've no idea how well mixed the honey is in the bucket and simply test a small amount using a single-use 'coffee stirrer' dipped into the top of the honey. This year, almost all the honey had a water content of 16-17%. I'll write about refractometers sometime in the future.

Packing up

Beekeeping is not an inexpensive pastime. Bees are expensive, hives are expensive and the associated - high volume - equipment for extracting, mixing, warming and jarring is also (often) expensive.

However, if looked after well, this equipment should last for years.

My first hive was a Thorne's 'Bees on a budget' cedar hive. It had a single brood box and three supers if I remember correctly. I purchased it second hand (together with the beesuit I wear for 80% of my beekeeping) and it's still used every season.

The beesuit has been repaired at least once and the hive received some additional screws to hold it together a bit better.

That super has probably yielded 10-15 kg of honey per year for the last 15+ years 😄. That's almost a quarter of a ton. It should receive a long-service award of some sort.

As a consequence of this longevity, over time, I've accumulated a lot of beekeeping equipment. This isn't too obvious when 25-30 hives are out in the fields, but it becomes an 'issue' when you reduce the hive numbers and it's all stacked up in big piles in and around the shed.

Once I'd finished the extracting I cleared and cleaned the room, washed and dried the extractor and then started packing the honey, the (spare) hives and the extractor {{8}} into the van for the trip to our new house.

It's a myth that moving house is one of the most stressful events in life. However, moving house at the same time as doing the honey harvest and preparing colonies for the winter is a lot of work, even if it's not particularly stressful.

The 1600 miles of driving, dozens of boxes packed and unpacked, and ~50 buckets of honey stacked and restacked, explains why this post appeared on Saturday morning rather than Friday afternoon.

Onward and upward.

Sponsor The Apiarist

The Apiarist covers 'the science, art and practice of sustainable beekeeping ... so much more than honey' and only exists because of the many hours spent hunched over a keyboard muttering nonsense and typing with two fingers.

If this, or other, posts has helped or inspired your beekeeping, or was amusing or enlightening, then please consider sponsoring The Apiarist.

Sponsorship costs less than £1/week annually, or little more than a large cappucino monthly. Sponsors receive the weekly posts, an irregular monthly newsletter, and an increasing number of sponsor-only content ... those starred ⭐ in the lists of posts.

Alternatively, help reduce my caffeine overdraft ... and please spread the word to encourage other beekeepers to subscribe.

Thank you.

{{1}}: Been there, done that, spent the evening lying on the floor in agony.

{{2}}: I save the sealed brood frames of stores to use in nucs, or supplement light colonies in the winter.

{{3}}: And the queen excluder.

{{4}}: Spotify's 70's Disco Hits since you asked.

{{5}}: Spotify's Ibiza classics 1990-2024 on the second day ... not as good, but some classic anthems if you like that sort of thing.

{{6}}: I had to add the usually having added the picture of the cedar super (below) which has eight, well-spaced and well-filled, frames. The majority of my supers contain 9 frames.

{{7}}: I remember reading that ~20% of the honey cannot be recovered in a radial extractor.

{{8}}: Actually, extractors, plural as I also have the hydropress for heather honey.

Join the discussion ...