The flow must go on

Except it doesn’t 🙁

And once the summer nectar flow is over, the honey ripened and the supers safely removed it is time to prepare the colonies for the winter ahead.

It might seem that mid/late August is very early to be thinking about this when the first frosts are probably still 10-12 weeks away. There may even be the possibility of some Himalayan balsam or, further south than here in Fife, late season ivy.

However, the winter preparations are arguably the most important time in the beekeeping year. If you leave it too late there’s a good chance that colonies will struggle with disease, starvation or a toxic combination of the two.

Long-lived bees

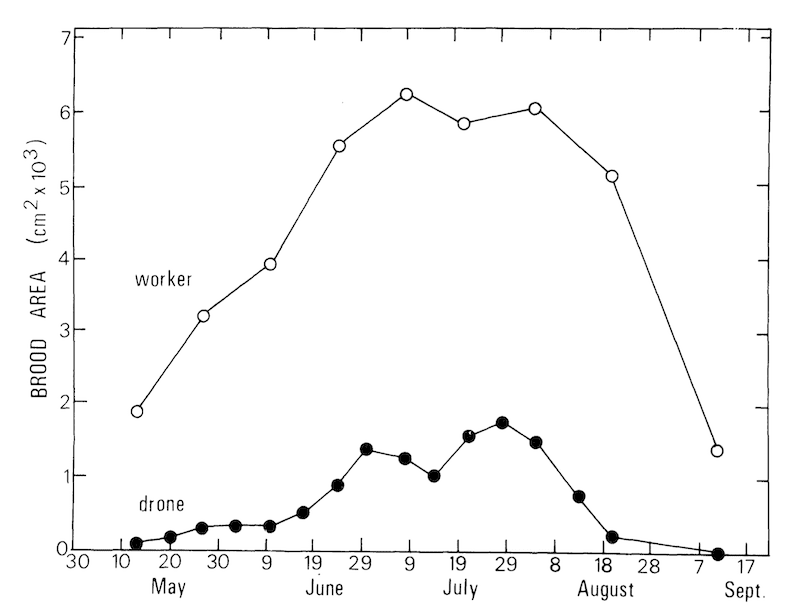

The egg laying rate of the queen drops significantly in late summer. I used this graph recently when discussing drones, but look carefully at the upper line with open symbols (worker brood). This data is for Aberdeen, so if you’re beekeeping in Totnes, or Toulouse, it’ll be later in the calendar. But it will be a broadly similar shape.

Seasonal production of sealed brood in Aberdeen, Scotland.

Worker brood production is down by ~75% when early July and early September are compared.

Not only are the numbers of bees dropping, but their fate is very different as well.

The worker bees reared in early July probably expired while foraging in late August. Those being reared in early September might still be alive and well in February or March.

These are the ‘winter bees‘ that maintain the colony through the cold, dark months so ensuring it is able to develop strongly the following spring.

The purpose of winter preparations is threefold:

-

- Encourage the colony to produce good numbers of winter bees

- Make sure they have sufficient stores to get through the winter

- Minimise Varroa levels to ensure winter bee longevity

I’ll deal with these in reverse order.

Varroa and viruses

The greatest threat to honey bees is the toxic stew of viruses transmitted by the Varroa mite. Chief amongst these is deformed wing virus (DWV) that results in developmental abnormalities in heavily infected brood.

DWV is well-tolerated by honey bees in the absence of Varroa. The virus is probably predominantly transmitted between bees during feeding, replicating in the gut but not spreading systemically.

However, Varroa transmits the virus when it feeds on haemolymph (or is it the fat body?), so bypassing any protective immune responses that occur in the gut. Consequently the virus can reach all sorts of other sensitive tissues resulting in the symptoms most beekeepers are all too familiar with.

However, some bees have very high levels of virus but no overt symptoms {{1}}.

But they’re not necessarily healthy …

Several studies have clearly demonstrated that colonies with high levels of Varroa and DWV are much more likely to succumb during the winter {{2}}.

This is because deformed wing virus reduces the longevity of winter bees. Knowing this, the increased winter losses make sense; colonies die because they ‘run out’ of bees to protect the queen and/or early developing brood.

I’ve suggested previously that isolation starvation may actually be the result of large numbers of winter bees dying because of high DWV levels. If the cluster hadn’t shrunk so much they’d still be in contact with the stores.

Even if they stagger on until the spring, colony build up will be slow and faltering and the hive is unlikely to be productive.

Protecting winter bees

The most read article on this site is When to treat? This provides all the gory details and is worth reading to get a better appreciation of the subject.

However, the two most important points have already been made in this post. Winter bees are being reared from late August/early September and their longevity depends upon protecting them from Varroa and DWV.

To minimise exposure to Varroa and DWV you must therefore ensure that mite levels are reduced significantly in late summer.

Since most miticides are incompatible with honey production this means treating very soon after the supers are removed {{3}}.

Once the supers are off there’s nothing to be gained by delaying treatment … other than more mite-exposed bees 🙁

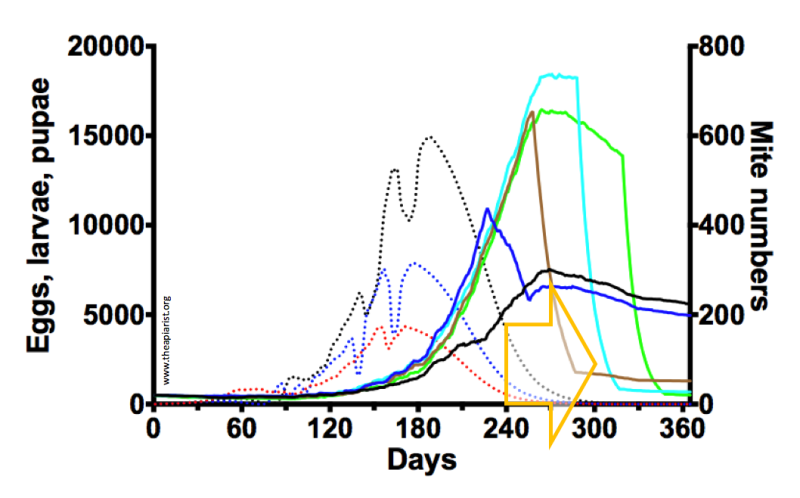

In the graph above the period during which winter bees are being reared is the green arrow between days 240 and 300 (essentially September and October). Mite levels are indicated with solid lines, coloured according to the month of treatment. You kill more mites by treating in mid-October (cyan) but the developing winter bees are exposed to higher mite levels.

In absolute numbers more mites are present and killed because they’ve had longer to replicate … on your developing winter bee pupae 🙁

Full details and a complete explanation is provided in When to treat?

So, once the supers are off, treat as early as is practical. Don’t delay until late September or early October {{4}}.

Treat with what?

As long as it’s effective and used properly I don’t think it matters too much.

Apiguard if it’s warm enough. Apistan if there’s no resistance to pyrethroids in the local mite population (there probably will be 🙁 ). Amitraz or even multiple doses of vaporised oxalic acid-containing miticide such as Api-Bioxal {{5}}.

This year I’ve exclusively used Amitraz (Apivar). It’s readily available, very straightforward to use and extremely effective. There’s little well-documented resistance and it does not leave residues in the comb.

The same comments could be made for Apiguard though the weather cannot be relied upon to remain warm enough for its use here in Scotland.

Another reason to not use Apiguard is that it is often poorly tolerated by the queen who promptly stops laying … just when you want her to lay lots of eggs to hatch and develop into winter bees {{6}}.

Feed ’em up

The summer nectar has dried up. You’ve also removed the supers for extraction.

Colonies are likely to be packed with bees and to be low on stores.

Should the weather prevent foraging there’s a real chance colonies might starve {{7}} so it makes sense to feed them promptly.

The colony will need ~20 kg (or more) of stores to get through the winter. The amount needed will be influenced by the bees {{8}}, the climate and how well insulated the hive is.

I only feed my bees fondant. Some consider this unusual {{9}}, but it suits me, my beekeeping … and my bees.

Bought in bulk, fondant (this year) costs £10.55 for a 12.5 kg block. Assuming there are some stores already in the hive this means I need one to one and a half blocks per colony (i.e. about £16).

These three photographs show a few of the reasons why I only use fondant.

- 11:42:56 … Ready

- Cut and open

- 11:44:18 … GO!

- It’s prepackaged and ready to use. Nothing to make up. Just remove the cardboard box.

- Preparation is simplicity itself … just slice it in half with a long sharp knife. Or use a spade.

- Open the block like a book and invert over a queen excluder. Use an empty super to provide headroom and then replace the crownboard and roof.

- That’s it. You’re done. Have a holiday 😉

- The timings shown above are real … and there were a couple of additional photos not used. From opening the cardboard box to adding back the roof took less than 90 seconds. And that includes me taking the photos and cutting the block in half 🙂

- But equally important is what is not shown in the photographs.

- No standing over a stove making up gallons of syrup for days in advance.

- There is no specialist or additional equipment needed. For example, there are no bulky syrup feeders to store for 48 weeks of the year.

- No spilt syrup to attract wasps.

- Boxed, fondant keeps for ages. Some of the boxes I used this year were purchased in 2017.

- The empty boxes are ideal for customers to carry away the honey they have purchased from you 😉

- The final thing not shown relates to how quickly it is taken down by the bees and is discussed below.

I’m surprised more beekeepers don’t purchase fondant in bulk through their associations and take advantage of the convenience it offers. By the pallet-load delivery is usually free.

Fancy fondant

Capped honey is about 82% sugar by weight. Fondant is pretty close to this at about 78%. Thick syrup (2:1 by weight) is 66% sugar.

Therefore to feed equivalent amounts of sugar for winter you need a greater weight of syrup. Which – assuming you’re not buying it pre-made – means you have to prepare and carry large volumes (and weights) of syrup.

Meaning containers to clean and store.

But consider what the bees have to do with the sugar you provide. They have to take it down into the brood box and store it in a form that does not ferment.

Fermenting stores can cause dysentry. This is ‘a bad thing’ if you are trapped by adverse weather in a hive with 10,000 close relatives … who also have dysentry. Ewww 😯

To reduce the water content the bees use space and energy. Space to store the syrup and energy to evaporate off the excess water.

Bees usually take syrup down very fast, rapidly filling the brood box.

In contrast, fondant is taken down more slowly. This means there is no risk that the queen will run out of space for egg laying. Whilst I’ve not done any side-by-side properly controlled studies – or even improperly controlled ones – the impression I have is that feeding fondant helps the colony rear brood into the autumn {{10}}.

Whatever you might read elsewhere, bees do store fondant. The blocks I added this week will just be crinkly blue plastic husks by late September, and the hives will be correspondingly heavier.

You can purchase fancy fondant prepared for bees with pollen and other additives.

Don’t bother.

Regular ‘Bakers Fondant’ sold to ice Chelsea buns is the stuff to use. All the colonies I inspect at this time of the season have ample pollen stores.

I cannot comment on the statements made about the anti-caking agents in bakers fondant being “very bad for bees” … suffice to say I’ve used fondant for almost a decade with no apparent ill-effects {{11}}.

It’s worth noting that these statements are usually made by beekeeping suppliers justifying selling “beekeeping” fondant for £21 to £36 for 12.5 kg.

Project Fear?

Colophon

The title of this post is a mangling of the well-known phrase The show must go on. This probably originated with circuses in the 19th Century and was subsequently used in the hotel trade and in show business.

The show must go on is also the title of (different) songs by Leo Sayer (in 1973, his first hit record, not one in my collection), Pink Floyd (1979, from The Wall) and Queen (1991).

{{1}}: It’s not clear why this is. Did they receive a smaller ‘dose’? Do they have a more robust immune response?

{{2}}: For example, Dainat et al., 2012 Dead or alive: deformed wing virus and Varroa destructor reduce the life span of winter honeybees App. Environ. Microbiol. 78:981-987 or van Dooremalen C et al. (2012) Winter Survival of Individual Honey Bees and Honey Bee Colonies Depends on Level of Varroa destructor Infestation. PLoS ONE 7: e36285.

{{3}}: Note that these comments relate to summer blossom honey. If you have bees at the heather until mid/late September it is likely you will need to manage Varroa levels before taking them to the moor.

{{4}}: Or later … I’ve sometimes received emails asking if it’s too late to treat in November … It’s not … but it is too late to treat in a way that benefits the bees.

{{5}}: Not multiple doses of trickled oxalic acid. This kills open brood and is poorly tolerated by the colony if used multiple times. Remember, the aim here is to treat and allow the colony to rear lots of healthy winter bees … don’t go killing them all before they even pupate.

{{6}}: In an area with a longer season this wouldn’t worry me but in Scotland it’s a risk I’m not prepared to take.

{{7}}: Precisely the same sort of things can happen during the ‘June gap’.

{{8}}: Some state that native black bees need as little as 10 kg to overwinter on.

{{9}}: Or downright weird!

{{10}}: Last season we continued harvesting pupae for experiments until mid-November.

{{11}}: Do they even contain ‘anti-caking’ agents? The 20 blocks of Südzucker I used this week state that the ingredients are Sugar, glucose syrup and water. Anti-caking agents are added to stop powders going lumpy. Whatever fondant is – solid, exceptionally viscous liquid? – it’s not a powder!

Join the discussion ...