The danger zone

… your bees are entering it about now.

I had hoped to start this post with a pretty picture of a row of colourful hives topped with a foot or more of snow. It would have been an easy picture to take … we’ve certainly got the snow.

It would have been an easy picture to take … had I been able to get to the apiary 🙁

I’m writing this in central Fife. We’ve had the heaviest snowfall I’ve seen here in 6 years (well over a foot) and the roads are just about impassable. Why risk a shunt for a pretty picture?

So here’s one taken earlier in the winter.

So what’s all this about the danger zone?

The danger zone

Bees that are rearing brood in the winter use stores at twice the rate when compared with bees that are not rearing brood.

How do we know this?

Clayton Farrar (1904 – 1970) was Professor of Entomology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He retired from his role as chief of the USDA Laboratories in Beekeeping in 1963. He’s well known (at least within certain beekeeping circles) for promoting two-queen honey production hives.

However, he also conducted lots of other studies on honey bees. Some of these were on the importance of pollen for brood rearing. Studies back in the 1930’s showed that when pollen was unavailable, brood rearing ceased.

Farrar compared the winter weight loss by colonies that were starved of pollen and those which had ample pollen. Those starved of pollen used their stores up only 50% as fast as those busy rearing brood.

Why do they use more stores?

I’ve recently discussed the winter cluster. In that post I made the point that the temperature of the winter cluster is carefully regulated.

In the absence of brood rearing, the core temperature of the cluster is about 18°C.

However, at that temperature honey bee development cannot happen {{1}}.

When brood rearing the colony must raise the temperature of the core of the cluster to ~35°C.

The bees in the cluster achieve this elevation of temperature by isometric flexing of their flight muscles.

And they need energy to do this work … energy in the form of sugar stores.

Biphasic stores use

What this means is that as a colony transitions from a broodless (which may or may not occur, depending upon your latitude, climate, temperature {{2}} ) winter period to rearing brood, they start consuming the stores faster.

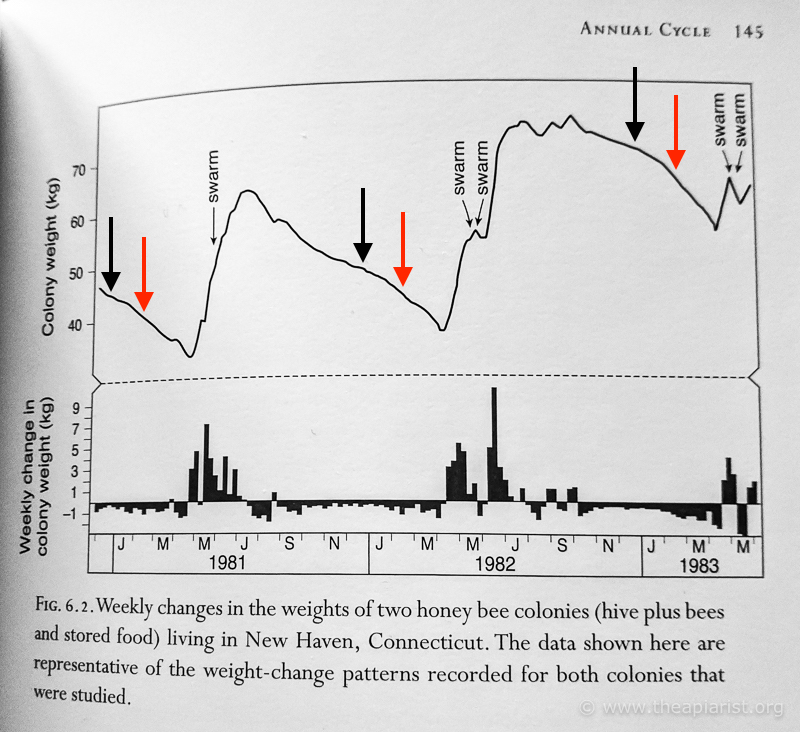

You can see this clearly in the right hand side of this graph from a paper from Tom Seeley, presented in his excellent book The Lives of Bees. This shows the winter weight change through two and a bit seasons. I’ve marked the approximate position of the winter solstice with a black arrow and mid-February (i.e. about now) with a red arrow.

Just focus on the 1928/83 winter as this most clearly shows an inflexion point in the rate of stores usage (we know it’s stores being used as it’s midwinter, so there’s no forage available).

The colony transitions from a maintenance rate to a brood rearing rate and the slope of the weight loss line steepens.

You can also see the same thing happening in the 80/81 and 81/82 winters, though it’s less obvious.

My colonies started rearing brood soon after the winter solstice. Yours might have not had a brood break at all.

However, in both cases the colony is likely to be rearing more brood now than it was 5-6 weeks ago.

Therefore it will be using more stores now … and so there’s an increased chance of the colony running out of stores.

It’s also appreciably colder over much of the UK now than it was a few weeks ago. We’ve had temperatures as low as -12°C this week, meaning the bees need to maintain a 49°C temperature differential to protect the developing brood in the hive.

This means that – all other things being equal – the colony will be using even more stores now than they were a month ago to maintain the same critical core temperature of the cluster for brood rearing.

Duunnn dunnn… duuuunnnn duun… duuunnnnnnnn dun dun dun …

That’s a rather poor attempt at spelling out the opening few bars of the Jaws theme 😉

The danger zone is in the late winter or early spring.

The colony must rear more brood to become strong enough to reproduce (swarm) in late April to early June.

And, from a beekeeping perspective, they must rear more brood to become a strong enough colony to properly exploit oil seed rape and other early nectars for the spring honey crop.

But there’s no forage available and/or it’s too cold to venture out for early nectar.

So the danger is that they starve to death 🙁

I’ve recently discussed determining whether your colony is rearing brood (and it will almost certainly have started by now, even if it’s taking a brief temporary break when the temperature plummeted) and also given an overview of ‘hefting’ hives and monitoring colony weight.

Fondant topups

If the colony feels light, or your records suggest it is dangerously light, you urgently need add a readily available (to the bees, if not to you) and easy to access source of sugar.

Syrup is not suitable at this time of the year. Even with lots of insulation, the space above the crownboard is a pretty chilly environment. A bucket of syrup placed there is likely to be simply ignored … at least until the ambient temperature has increased.

By which time it might be too late.

If the colony feels light they need stores now, not when it warms up (though they’ll also need stores then … if they survive that long).

Fondant is the stuff to use.

I’ve written extensively about it previously and I buy it by the pallet load. It stores perfectly for months or years, so I always have it available. I use it for almost all my bee feeding.

You can also make it relatively easily {{3}}.

Fondant is ~80% sugar. It’s also malleable but semi-solid … a bit like plasticine.

But it tastes appreciably better 😉

I’ve found the best way to provide fondant is in transparent (or at least translucent) shallow food containers.

In the photo above the clear(ish) ones are much better than the brown or green ones. Better still are the double-area ones you buy chicken breasts in {{4}}. These are wide but shallow and can accommodate at least 2 kg of fondant.

Where to place the fondant

I stressed that the fondant must be easy to access by the bees.

There’s no point in adding it if they don’t have immediate access to it.

And if it’s -8°C outside the bees are not going to be wandering around looking for food … any that leave the cluster will soon get chilled, become torpid and perish.

You therefore need to put the fondant directly in contact with the bees.

Often the advice is to provide the fondant over the hole in the crownboard.

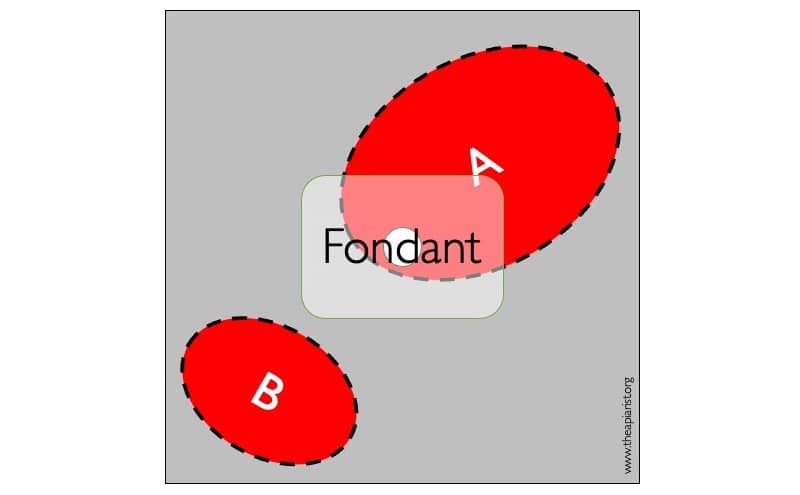

However, consider the this diagram.

If your bees form a large cluster – like A above – they are in contact with the fondant that has been placed directly above the central feed hole in the crownboard.

And, if they stay there, all will be OK.

But what about the smaller cluster (B)?

These bees don’t have direct access. If the weather is cold enough and the space above the crownboard is badly insulated the fondant might as well have been left in the packet.

In the shed 🙁

I therefore add the fondant under the crownboard.

I place the fondant block, inverted, covering part of the cluster. They can immediately access it and they will soon use it if they need it.

The photo above shows why clear or translucent containers are preferable – you can easily tell how much of the fondant remains.

In the photos above the cluster is located approximately centrally within the brood box. However, think back to the colony I discussed a fortnight ago. In that, the cluster was tight up against the polystyrene side wall of the hive, some distance from a central hole in the crownboard (if mine had a central hole 😉 ).

Headspace

These plastic food containers are about 5 cm deep. Filled to the brim they can hold about 1.2 kg of fondant. That might well not be enough … hence my preference for the larger containers.

Or just use two of them …

Fondant absorbs moisture from the environment, softening the surface. With the fondant directly in contact with the top bars of the frames and the bees, this softened fondant is readily used.

I made the mistake once of wrapping the fondant in clingfilm and providing a hole for the bees to access it. Over time they drag the shredded clingfilm down into the hive, incorporating it into brace comb.

It makes a right mess. Avoid clingfilm.

If you are concerned about sloppy fondant dribbling down onto the cluster (something I’ve noticed a couple of times with either very weak colonies or in very damp environments) you can cover the face of the block with a sheet of plastic. Cut a 2 cm square hole in this and place it over the centre of the cluster.

And how do you accommodate this 5 cm block of fondant under the crownboard?

You can use a 5 cm deep eke, with your normal crownboard on top.

Alternatively, you can build crownboards that have a single bee space on one side and an integral ‘eke’, in the form of a 5 cm deep rim, on the other.

I built a few of these many years ago, with perspex and an inbuilt block of ‘Kingspan’ insulation. They work really well.

When you need the headspace – for example for a block of fondant – you simply invert the crownboard and place the insulation on top, under the roof.

What, no fondant?

If you haven’t got any fondant, don’t despair.

But also don’t delay while you try and source some fondant.

Fondant is sugar after all, and everyone should be able to get sugar.

Despite having a mountain of fondant squirreled away, I still keep a few bags of granulated sugar ‘just in case’.

Cut a 2 x 2 cm hole in the front of bag of sugar and add about a half teacup full of water. Let it soak in for a few minutes. Add less than you think is needed … you can always add a bit more.

You want to dampen the sugar, not dissolve it. The aim is to be able to invert the bag directly over the cluster {{5}}.

So do that as soon as you can.

Bees need water to be able to ‘eat’ granulated sugar, so dampening it helps both keep it in the bag and saves them doing extra work collecting condensation from the hive walls.

And, just to avoid any ambiguity, only used white granulated sugar.

It takes bees to make bees … and honey

Colonies that are strong early in the season are better able to exploit the spring nectar, including that from oil seed rape.

Some beekeepers feed their colonies thin syrup (1:1 w/v) in early spring to boost brood rearing in time to have booming colonies ready for the rape.

I’ve not done this, or ever felt I really needed to. However, I’m not commercial and do not rely on the honey harvest to feed the family, pay the kids’ school fees or fuel the Porsche.

And, other than feeding the family, I don’t know any commercial beekeepers who rely on honey sales for those other things either {{6}}.

Usually the combination of young queens, low Varroa levels and ample autumn feeding produces colonies strong enough for my beekeeping in the spring.

Rapidly expanding colonies in March and early April require good amounts of brood to be reared during the dark winter days in January and February. After all, you cannot rear lots of bees without having lots of bees available to do the brood rearing.

This is an area where it is beneficial to have young queens heading the colony. These lay later into the autumn, resulting in more winter bees.

If these bees are healthy and well fed the colony should have a flying start to the following season, if you’ll excuse the pun.

But check them nevertheless as they enter ‘the danger zone’.

As you add your third or fourth super to a hive in early May, think back to that cold, wet day three months earlier when you gave them an extra block of fondant … and give yourself a pat on the back 😉

Notes

I finally managed to get out a couple of days after it stopped snowing.

The two hives on the right have a 4 mm thick Correx roof, directly on top of a 5 cm thick block of Kingspan. Going by the amount of snow still sitting on top of these hives they’re not losing too much heat through the roof 🙂

The Danger Zone was a song by Kenny Loggins that featured in the 1986 movie Top Gun. In retrospect, it’s a pretty cheesy movie. However, 35 years ago it was the first VHS videotape I purchased. It had a Dolby soundtrack and, played loud through the stereo speakers while sitting close to the TV (to get that ‘widescreen’ cinema feeling) it sounded pretty good 😉

I do not often listen to Kenny Loggins but when I do, so do my neighbors …

{{1}}: The correct temperature really is critical for successful brood rearing – worker bees reared at 32°C, just 3°C below the normal temperature, show behavioural abnormalities and other defects.

{{2}}: And possibly a host of other factors.

{{3}}: I’ve not done this (for obvious reasons if you look at the photograph above) so cannot provide a recipe I’ve used. Here is one from a trustworthy beekeeping source.

{{4}}: Or at least I buy chicken breasts in … for all I know you are vegetarian. Or you might ‘grow your own’ and keep chickens.

{{5}}: Again, under the crownboard. You might need a double height eke or a super to provide the necessary headspace.

{{6}}: Though I’m told there’s at least one individual in the beekeeping business who drives a Lamborghini … it’s not me.

Join the discussion ...