Teaching in the bee shed

An observant beekeeper never stops learning. How the colony responds to changes in forage and weather, how swarm preparations are made, how the colony regulates the local environment of the hive etc.

Sometimes the learning is simple reinforcement of things you should know anyway.

Or knew, but forgot. Possibly more than once.

If you forget the dummy board they will build brace comb in the gap ?

There’s nothing wrong with learning by reinforcement though some beekeepers never seem to get the message that knocking back swarm cells is not an effective method of swarm control ?

Learning from bees and beekeeping

More generally, bees (and their management) make a very good subject for education purposes. Depending upon the level taught they provide practical examples for:

- Biology – (almost too numerous to mention) pollination, caste structure, the superorganism, disease and disease management, behaviour

- Chemistry – pheromones, sugars, fermentation, forensic analysis

- Geography and communication – the waggle dance, land use, agriculture

- Economics – division of labour (so much more interesting than Adam Smith and pin making), international trade

- Engineering and/or woodwork – bee space, hive construction, comb building, the catenary arch

There are of course numerous other examples, not forgetting actual vocational training in beekeeping.

This is offered by the Scottish Qualifications Authority in a level 5 National Progression Award in Beekeeping and I’ve received some enquiries recently about using a bee shed for teaching beekeeping.

Shed life

For our research we’ve built and used two large sheds to accommodate 5 to 7 colonies. The primary reason for housing colonies in a shed is to provide some protection to the bees and the beekeeper/scientist when harvesting brood for experiments.

On a balmy summer day there’s no need for this protection … the colonies are foraging strongly, well behaved and good tempered.

But in mid-March or mid-November, on a cool, breezy day with continuous light rain it’s pretty grim working with colonies outdoors. Similarly – like yesterday – intermittent thunderstorms and heavy rain are not good conditions to be hunched over a strong colony searching for a suitable patch containing 200 two day old larvae.

Despite the soaking you get the colonies are still very exposed and you risk chilling brood … to say nothing of the effect it has on their temper.

Or yours.

Bee shed inspections

Here’s a photo from late yesterday afternoon while I worked with three colonies in the bee shed. The Met Office had issued “yellow warnings” of thunderstorms and slow moving heavy rain showers that were predicted to drift in from the coast all afternoon.

All of which was surprisingly accurate.

For a research facility this is a great setup. The adverse weather doesn’t seem to affect the colonies to anything like the same degree as those exposed to the elements. Here’s a queenless colony opened minutes before the photo above was taken …

Inside the shed the bees were calmly going about their business. I could spend time on each frame and wasn’t bombarded with angry bees irritated that the rain was pouring in through their roof.

Even an inexperienced or nervous beekeeper would have felt unthreatened, despite the poor conditions outside.

So surely this would be an ideal environment to teach some of the practical skills of beekeeping?

Seeing and understanding

Practical beekeeping involves a lot of observation.

Is the queen present? Is there brood in all stages? Are there signs of disease?

All of these things need both good eyesight and good illumination. The former is generally an attribute of the young but can be corrected or augmented in the old.

But even 20:20 vision is of little use if there is not enough light to see by.

The current bee shed is 16′ x 8′. It is illuminated by the equivalent of seven 120W bulbs, one situated ‘over the shoulder’ of a beekeeper inspecting each of the seven hives.

On a bright day the contrast with the light coming in through the windows makes it difficult to see eggs. On a dull day the bulbs only provide sufficient light to see eggs in freshly drawn comb. In older or used frames – at least with my not-so-young eyesight – it usually involves a trip to the door of the shed (unless it is raining).

It may be possible to increase the artificial lighting using LED panels but whether this would be sufficient (or affordable) is unclear.

Access

Observation also requires access. The layout of my bee shed has the hives in a row along one wall. The frames are all arranged ‘warm way’ and the hives are easily worked from behind.

Inevitably this means that the best view is from directly behind the hive. If the shed was used as a training/teaching environment there’s no opportunity to stand beside the hive (as you would around a colony in a field), so necessitating the circulation of students within a rather limited space to get a better view.

A wider shed would improve things, but it’s still far from ideal and I think it would be impractical for groups of any size.

And remember, you’re periodically walking to and from the door with frames …

Kippered

If you refer back to the first photograph in this post you can see a smoker standing right outside the door of the shed.

If you use or need a smoker to inspect the colonies (and I appreciate this isn’t always necessary, or that there are alternative solutions) then it doesn’t take long to realise that the smoker must be kept outside the shed.

Even with the door open air circulation is limited and the shed quickly fills with smoke.

If you’ve mastered the art of lighting a properly fuelled efficient smoker the wisp of smoke curling gently up from the nozzle soon reduces visibility and nearly asphyxiates those in the shed.

Which brings us back to access again.

Inspections involve shuttling to and from the door with frames or the smoker, all of which is more difficult if the shed is full of students.

Or bees … which is why the queen excluder is standing outside the shed as well. I usually remove this, check it for the queen and then stand it outside out of the way.

Broiled

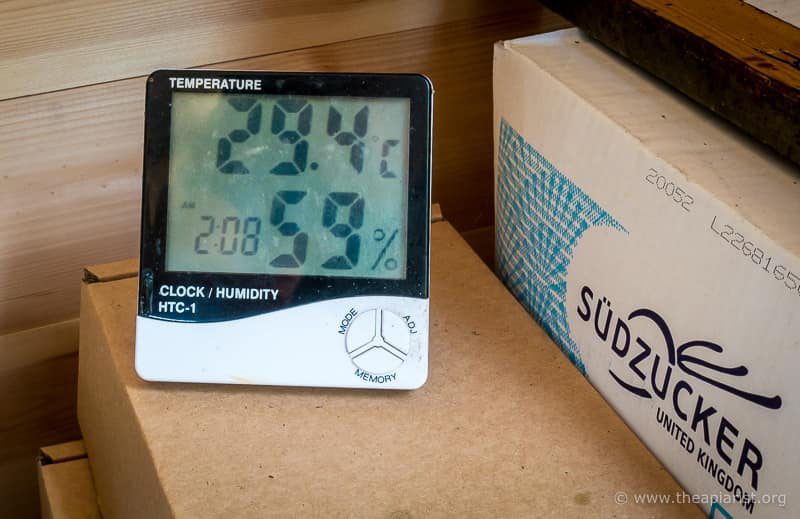

In mid-March or November the shed is a great place to work. The sheltered environment consistently keeps the temperature a little above ambient.

Colonies seem to develop sooner and rear brood later into the autumn {{1}}.

But in direct sunlight the shed can rapidly become unbearably warm.

All the hives have open mesh floors and I’ve not had any problems with colonies being unable to properly regulate their temperature.

The same cannot be said of the beekeeper.

Working for any period at temperatures in the low thirties (Centigrade) is unpleasant. Under these conditions the shed singularly fails to keep the beekeeper dry … though it’s sweat not rain that accumulates in my boots on days like this.

Bee shelters

For one or two users a bee shed makes a lot of sense if you:

- live in an area with high rainfall (or that is very windy and exposed) and/or conditions where hives would benefit from protection in winter

- need to inspect or work with colonies at fixed times and days

- want the convenience of equipment storage, space for grafting and somewhere quiet to sit listening to the combined hum of the bees in the hives and Test Match Special ?

But for teaching groups of students there may be better solutions.

In continental Europe {{2}} bee houses and bee shelters are far more common than they are in the UK.

I’ve previously posted a couple of articles on German bee houses – both basic and deluxe. The former include a range of simple shelters, open on one or more sides.

A bee shelter

Something more like this, with fewer hives allowing access on three sides and a roof – perhaps glazed or corrugated clear sheeting to maximise the light – to keep the rain off, might provide many of the benefits of a bee shed with few of the drawbacks.

{{1}}: We continued to harvest pupae until mid-November last season and all colonies overwintered very well.

{{2}}: I can still write this though it unfortunately looking like I’ll need to find an alternative phrase by late October.

Join the discussion ...