Supersedure

Supersedure is the replacement of the queen – due to age or infirmity – by a new one reared in the same colony. Significantly the colony is at no point queenless, and may actually have two laying queens during the overlap period. Ted Hooper (in his Guide to Bees and Honey) states that 5% of colonies with two year old queens – at least of the strain of bees he used – actually have two queens in the colony in the autumn and they can often be found laying on the same frame.

I rarely inspect colonies in the autumn and have never seen two queens in a colony, let alone on the same frame. However, I’m well aware the process goes on undetected … or at least undetected until the following spring.

I’ll check a colony in mid-August and find the clipped, marked laying queen I expect. However, the following April – well before the swarm season starts here – I’ll find an unmarked and unclipped queen heading the colony {{1}}.

Supersedure is a colony survival mechanism.

It ensures the colony is headed by a queen that will produce sufficient brood to be strong enough to collect an excess of nectar and overwinter successfully, with the intention of swarming the following season. It is therefore perhaps unsurprising that it is considered a late season event, though it can occur at other times when there are drones and weather suitable for queen mating.

The term supersedure appears to have first been used in the American Bee Journal in 1872:

Only in cases of supersedure are the young queens allowed to hatch, and then frequently the young and the old queen remain peaceably in the hive.

Swarming, emergency and supersedure queen cells

Supersedure is relatively poorly understood, not least because it is difficult to reliably induce. Inevitably, because it involves the production of a new queen, it necessitates the generation of queen cells.

There are three conditions under which the colony produces queen cells:

- the swarming impulse, induced by overcrowding and the consequent reduction in the concentration of queen pheromones (and other things)

- the emergency response, when the queen suddenly disappears or is killed. With the exception of beekeeper-induced snafu’s it’s difficult to imagine a natural event that results in the immediate removal of the queen. However, because it is so easy to recapitulate, this is the best studied situation in which queen cells are produced

- supersedure

In the first of these a strong colony tends to produce excess queen cells resulting in a prime swarm (headed by the original mated queen) followed by several cast swarms (headed by virgins), leaving one queen to get mated and continue the original colony. It’s not unusual to find a dozen or more queen cells in a colony intent on swarming … or even on a single frame, with more on other frames.

In contrast, during supersedure or the emergency response the goal of the colony is replacement, not reproduction, so a smaller number of queen cells tend to be started.

Queen cell number and position

However, don’t rely on the number or position of the queen cells as the sole indication of what’s happening in the colony.

You’ll often read that a single cell, located in the middle of a central frame, is an indication that the colony is planning to supersede the queen.

A classic supersedure cell … or is it?

It might be … but I’m a lot more confident if I also find the original queen and eggs in the hive.

The colony is very selective when choosing larvae for queen rearing during the emergency response – for example, consider the previous posts on Who’s the daddy? and Picking winners – so a lone queen cell, wherever it is located, could still indicate the original queen is AWOL. Look again for her, and for the presence of eggs before you conclude it’s supersedure rather than emergency requeening.

Personally I place little importance on the location of the queen cell.

In contrast, I have a lot of confidence that the colony choose the egg or larvae for queen rearing wisely, so the position of the cell most probably reflects the location of the most suitable larva.

Finally, remember that if you find a sealed queen cell it’s likely that the colony has swarmed, unless:

- you find the queen and eggs (in which case it may well be supersedure), or

- the queen is clipped and present (in which case they’ve either tried to swarm and returned, or will swarm … do something!) {{2}}

Dave Cushman states that supersedure cells are always started from eggs laid in (or moved to?) queen cups. If this is the case – and I’ve no reason to doubt it – then the position of the queen cup will determine that of the final cell.

Induction of supersedure

Since supersedure is a colony survival mechanism it must be induced when the colony senses that the queen is underperforming to such an extent that colony survival is threatened.

Simply laying spotty brood, or not laying 2000 eggs a day isn’t sufficient … there are thousands of colonies in the UK where queens are behaving like this and the majority are not going to be superseded.

The age of a queen also has a bearing on whether supersedure occurs, with older queens more likely to be superseded. In addition, some strains of bees – in particular native black bees Apis mellifera mellifera – are much more likely to supersede.

My ’Heinz 57 varieties’ Fife mongrels relatively rarely supersede, but ~20% of my native black colonies on the west coast are headed by supersedure queens.

Hopalong Cassidy …

The injury of a queen, for example the paralysis of one of her fore- or hindlegs, will often result in supersedure. Historically beekeepers attempted to induce supersedure by cutting off one of the legs of the queen.

This is not something I’ve done or would condone.

Dave Cushman explains that this ‘works’ by reducing the deposition of queen footprint pheromone, and that this reduction is what accounts for supersedure … but, as we shall see, it may be a bit more complicated than that.

Packages and queen supersedure

A ‘package’ is a box of bees and a caged queen. You can think of it as a frameless nuc. Typically it contains about 1.5 kg of mixed (i.e. from multiple colonies) workers in a mesh-sided box, together with a mated queen in a cage. It’s a convenient way to purchase bees – easy to ship, no brood disease, less expensive etc.

Installing a package of bees

I’ve previously bought packaged bees for research. In the UK it’s probably a less common way to purchase bees than it is in the US or (perhaps) Europe.

You install a package by dumping the bees into a hive containing frames, add the queen in a cage from which she can be released, feed copiously for a week or two and voila!, you have a fully functioning colony.

However, the queen provided with the package is sometimes very quickly changed. Studies in the USA indicate that over 25% of queens in installed packages were replaced within a few weeks (Withrow et al., 2019).

This isn’t swarming or due to the queen being killed, it’s supersedure.

Empty boxes after installing purchased packages of bees

It’s not unusual for the recently installed colony to start replacing the queen before an entire brood cycle is completed.

And these observations provide an opportunity for studies on the factors that induce supersedure.

Brood pheromones

Whilst an underperforming queen might produce reduced amounts of footprint pheromone {{3}}, another way that the colony could assess her performance is through the level of brood in the colony.

If there’s little or no brood, or less than ‘expected’ (whatever that means), perhaps it’s because the queen is failing? {{4}}

Essentially the amount of open brood is a measure of the fecundity of the queen.

Although bees can count they can’t count higher than about 4, so they clearly don’t determine the amount of brood by counting it.

Instead – and it will come as ‘precisely no surprise whatsoever’ to anyone who knows anything about bees – they can determine the amount of brood by detecting the level of brood pheromone. At least, they can probably determine if there is some/enough and whether it is increasing or decreasing. Brood pheromone levels similarly have a bearing on the production of winter bees.

Or, to be a little more specific, brood pheromones, as there are more than one.

And a package, at least when first installed, has no brood pheromone(s) as it has no brood.

The high levels of supersedure seen using packages prompted David Tarpy and colleagues (Tarpy et al., 2021) to investigate the role of brood pheromone on colony establishment and queen replacement (i.e. supersedure).

Specifically they investigated the influence of brood ester pheromone (BEP) which can be synthesised vs. natural open brood, on these phenomena.

BEP and colony establishment

The study conducted was relatively simple. 45 packages were installed, one third had no prior or ongoing exposure to BEP or brood and acted as the negative control (these were installed in exactly the same way as thousands of beekeepers install packages every season), one third were exposed to synthetic BEP when the package was made and for 10 days after installation, and one third were installed into hives containing a frame of (unrelated) open brood.

In terms of colony establishment (speed of build up etc.) packages installed with a frame of open brood exhibited a statistically significant enhancement in brood rearing over control packages. In addition to starting with more brood (by definition, as they were introduced to a hive containing a frame of open brood), they also ended with more brood i.e. the colonies were stronger at the end of the study after the rate of colony expansion had plateaued.

BEP-exposed colonies performed better than controls, but not as well as packages exposed to open brood. Synthetic BEP alone is therefore not able to completely recapitulate the boost produced by open brood.

It should be noted here (because I’m not going to mention it again) that older larvae produce higher levels of BEP, whereas younger larvae also produce another pheromone termed volatile brood pheromone (vBP).

A frame of open brood contains a mixture of ageing larvae so would also have been producing vBP … this might account for the additional boost in colony establishment. This will need further testing.

I don’t find it surprising that a defined single brood pheromone cannot fully substitute – at least in influencing colony expansion – for the likely complexity produced by a thousands of larvae of a range of ages.

However, what was the impact on supersedure?

BEP vs. brood and supersedure

The differences in colony establishment were significant (mathematically speaking), but they weren’t huge (perhaps at most ~20% stronger at the end of the study period).

In contrast, the influence on supersedure was much more striking.

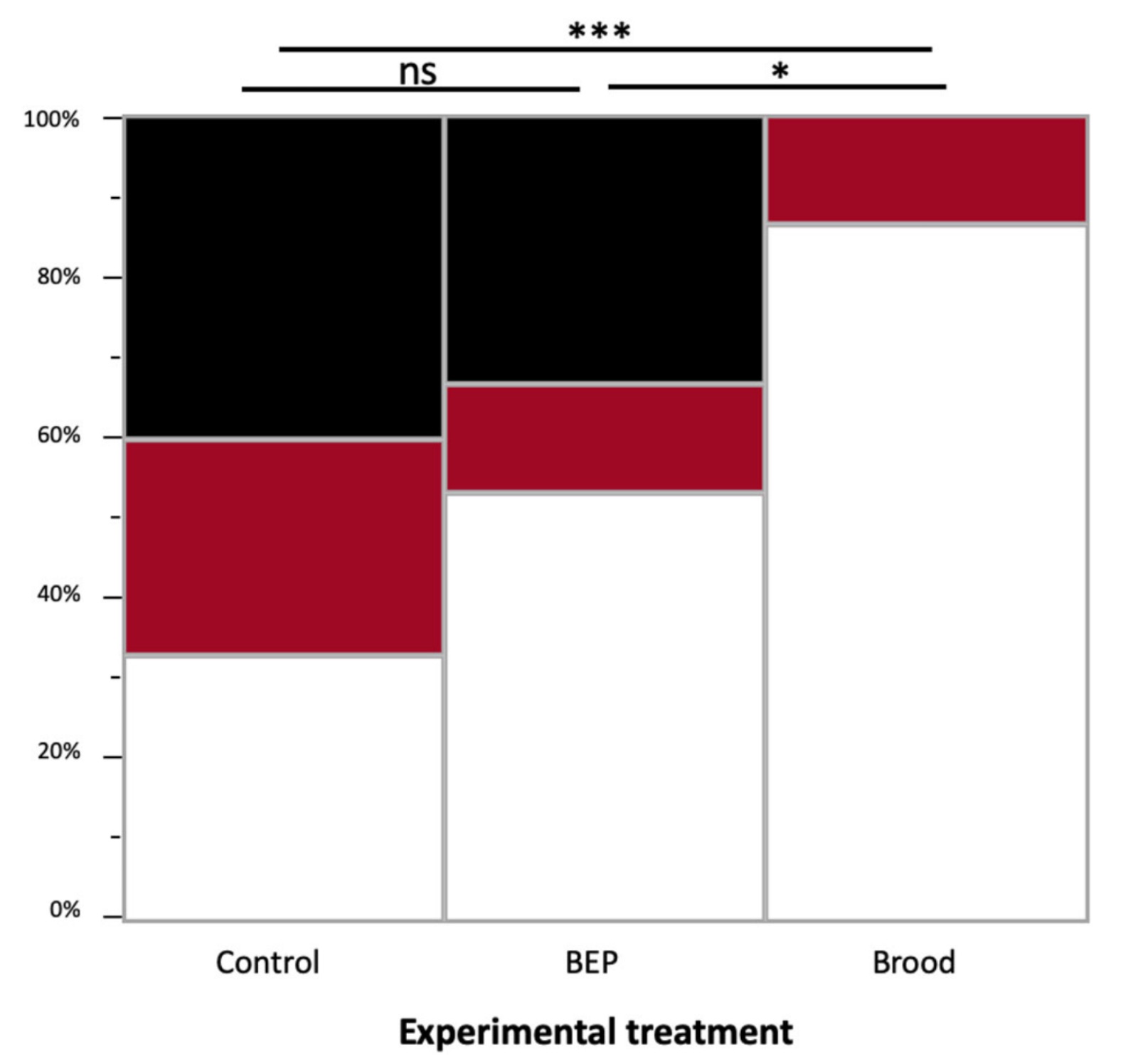

Retained (white), early (red) or late (black) queen supersedure and treatment – click for legend

Of the 45 packages installed almost 50% of them reared new queens within 12 weeks.

If I’d paid £180-240 for a 1.5 kg package (yes, that’s the going rate for 2024 🙁 ) containing a mated, laying queen I would not be pleased to find the queen being replaced within 3 months.

However, the fate of the supplied queen was very dependent on how the package was installed. Control packages (i.e. no BEP or brood) only retained 33% of the original queens, BEP-exposed packages retained 53% and those installed onto brood kept 87% of the supplied queens.

The Control and BEP-exposed queen replacement did not necessarily occur immediately. Over 50% of replaced queens were superseded after the colony had reared a complete cycle of new brood (for convenience defined as 5 weeks after installation).

Unsurprisingly, the difference (33% vs 87%) between the absence and presence of a frame of brood was highly statistically significant.

If you’re purchasing package bees next year why not try installing them into a hive containing a frame of open brood? It can’t do any harm, and may well do a lot of good {{5}}.

In addition to recording queen replacement, Tarpy and colleagues also busied themselves counting queen cells. The number produced was unrelated to the likelihood of the queen being replaced. On average, superseding colonies produced ~5 queen cells (some being subsequently torn down), and up to 25.

Again, don’t assume queen cell numbers allow differentiation of swarming and supersedure 😉 .

Conclusions of the Tarpy et al., study

The dramatic reduction in supersedure seen in the presence of brood but not BEP suggests other brood pheromones (or something else to do with open brood) help retain the original queen, perhaps in conjunction with BEP.

The paper largely focuses on the benefits of installing packages onto open brood, rather than the mechanism by which these benefits are realised.

The mechanism could be relatively straightforward; the presence of open brood simply ‘signalling’ to the workers that the queen is fecund and so does not need replacing.

However, remember the timing of queen supersedure.

Over 50% of supersedures occurred after 5 weeks suggesting that the ‘open brood influence’ is more likely indirect, where the presence of open brood stimulates the workers to provide additional support (nourishment, cell preparation, whatever) to the queen, so increasing her laying rate and therefore apparent fecundity.

There are other interpretations {{6}} though I suspect these are less likely and are also not supported by other literature I don’t have time or space to review.

The queens used in this study were ’newly mated’. The 87% ‘survival’ rate with open brood shows they were satisfactory. Queens from mini-nucs or that have been ‘banked’ for long periods – both situations where the queen is not laying (or laying at a reduced rate) – can appear sub-standard and are more likely to be superseded.

Supersedure is a beneficial trait … it’s good when it happens, often undetected, ‘in the background’, saving a potentially doomed colony.

Are there ways that it can be exploited by the beekeeper?

Inducing supersedure the ethical way

I usually write about beekeeping things I’ve done, but here’s something I’m in the middle of doing. It might not work, but much more experienced beekeepers than me suggest it works acceptably well and I reckoned it was ‘worth a punt’.

A queen that’s laying well, not limping (!) and apparently healthy {{7}} will not normally be superseded by the colony.

- firstly, they won’t produce supersedure cells.

- secondly, if a sealed queen cell is added by the beekeeper to a queenright colony, the colony will tear the cell down and kill the developing queen. They will also do this if you add a queen cell too soon after removing the original queen, presumably due to the presence of circulating queen pheromones.

This ‘tearing down’ of the cell involves the workers chewing through the sidewall of the cell. Apparently they go through the sidewall because the pupal cocoon is thinner there than at the tip of the cell.

JzBz queen cell protectors

It’s for this reason that queen cell protectors were invented. I’ve purchased a variety of different types of these protectors – in plastic (which tend to be a bit on the small side in my view), metal or bamboo. All restrict access to the sides of the cell but allow the queen to emerge from the tip.

Apple pies

However, far easier than these commercial products is a turn or two of aluminium foil. This can be wrapped around the cell leaving the tip exposed and the workers are unable to tear the cell down.

Although you can remember to include a 50 m roll of Bacofoil in your bee bag I’ve found it’s better to procure a packet of individual Bramley apple pies, each occupying a tin foil container.

I’ve eaten the contents

Eat the pie and then use the foil.

Other pies may work {{8}} but I can guarantee that tin foil from Bramley apple pies does 😉 .

OK, back to supersedure

What happens if you add a suitably protected sealed queen cell to a queenright colony?

Roger Patterson claims that in ~80% of cases the new queen supersedes {{9}} the original queen in the hive.

Spare queen cells

After the most recent round of queen rearing I had a few cells ‘spare’ and a couple of colonies destined for either uniting or queen replacement. Rather than removing the old queen and adding a protected cell, or removing the old queen and waiting an hour or three before adding an unprotected cell {{10}}, I simply added foil-wrapped cells to the queenright hives.

Foil-wrapped cell

The larvae had been grafted into Nicot plastic cups and the creamy yellow plastic cup holders have convenient ‘ears’ to push into comb to hold the cell between frames of brood. I scoffed a couple of apple pies, cut the foil up using my queen clipping scissors {{11}}, wrapped the cell and pushed it into the comb. It took no more than 1 minute (including consuming the pies). No need to even look for the laying queen.

It will be easy enough to determine whether the original queens are superseded (as they were clipped and marked 😉 ).

I’ll check the state of the queen cells next week and, assuming they’ve emerged OK, will look for a new mated laying queen in the hives a fortnight or so after that.

Natural and artificial supersedure

This ‘protected queen cell “supersedure”‘ isn’t true supersedure as the new queen is being imposed on the colony, rather than the workers deciding to replace her.

In natural supersedure the older queen is probably finally ejected by the workers – either literally or, more probably, through starvation.

What is the fate of the old queen in this beekeeper-induced artificial supersedure?

Do the queens battle it out? Does the strength of the new queen’s pheromones ensure she gets support from the colony at the expense of the old queen? Is the success of this supersedure dependent upon the older queen being old (there’s a difference).

I’m asking the questions as I don’t know the answer.

’No cost option’

Supersedure offers a survival mechanism for colonies with a failing queen. I think of it as a sort of evolutionary ‘no cost option’. If the colony judges the queen might fail they rear a supersedure queen. If conditions are suitable for queen mating and she gets mated then brood rearing continues.

Queen mating success is probably ~80-90% (at least in free living colonies where it has been measured). Some supersedure queens will fail to get mated (no drones, too cold or wet), in which case the original queen will carry on. She may or may not subsequently fail, and if she does the colony will probably perish, but there was little or no cost to the colony in attempting to supersede her.

It might be significant that most supersedure occurs in autumn. If the queen is from the current season e.g. a cast swarm, but poorly mated, then the long-term survival of the colony is dubious. Conversely, if an ageing queen is failing, superseding her in the autumn may mean the colony survives to the following spring.

Winter bees are produced in late summer and early autumn. These are the population that live for at least 5-6 months rather than the 5-6 weeks of summer bees. Because supersedure causes no brood break there will be no impact on the number of these winter bees (if unsuccessful), and the number might be boosted if supersedure if successful.

Pretty … but not so good for queen mating

If you replace your queens annually you may never observe supersedure. If you don’t routinely replace your queens or – particularly – if you successfully keep bees in the colder, wetter, windier north and west of the UK (or, probably, the USA and Canada) then you may well depend upon it.

Please support further articles by becoming a supporter or funding the caffeine that fuels my late night writing ...

Thank you

References

Tarpy, D.R., Talley, E., and Metz, B.N. (2021) Influence of brood pheromone on honey bee colony establishment and queen replacement. Journal of Apicultural Research 60: 220–228 https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2020.1867336.

Withrow, J.M., Pettis, J.S., and Tarpy, D.R. (2019) Effects of Temperature During Package Transportation on Queen Establishment and Survival in Honey Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 112: 1043–1049 https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toz003.

{{1}}: And, yes, I might not inspect my colonies much in the late summer/autumn but I know they haven’t swarmed.

{{2}}: Under these conditions you often will not find eggs.

{{3}}: Formally, has this been shown? I don’t think so, though I acknowledge that an injured queen hobbling around the frames might well.

{{4}}: Of course, at some times there will be little/none e.g. midwinter, but there are other factors at play then.

{{5}}: Or, better still, rear your own and save yourself £240.

{{6}}: A direct impact on the queen that provides either short- or long-term boosts to her egg laying?

{{7}}: Nosema infection is supposed to induce supersedure, but I need to read more about this.

{{8}}: And I’m busily doing research on the suitability of Bakewell tarts at the moment.

{{9}}: Blue text at the bottom of the page.

{{10}}: Important if I’d not eaten all the pies.

{{11}}: Probably irretrievably blunting them.

Join the discussion ...