Supering

Something short and sweet this week {{1}} … though perhaps ‘tall and sweet’ would be preferable as I’m going to discuss supering.

The noun supering means ‘the action or practice of fitting a super to a beehive’ and dates back to 1840:

Duncan, James. Natural History of Bees Naturalist’s Library VoI. 223 The empty story which is added, may be placed above, instead of below the original stock, and the honey will thus be of a superior kind. This mode of operating is called super-ing, in contra-distinction to nadir-ing.

I don’t quite understand the description provided by here. Adding a super underneath the colony (original stock) is unlikely to lead to it being used as a honey store. Bees naturally store honey to the side and above the brood nest.

And does James Duncan mean the honey is superior because it’s better? Or is he using superior in its zoological sense meaning ‘at or near the highest point’? {{2}}

So … let’s get a few definitions out of the way first.

- Supering – the addition of a super to a hive, which could be either:

- Top-supering – adding a super to the top of a stack of existing supers, or

- Bottom-supering – adding a super below any existing supers, but above the brood box(es)

- Nadiring – the addition of a super below an existing brood box (which won’t be mentioned again in this post {{3}}.

I prefer the term top- or bottom-supering as the alternative over- or under-supering could be misinterpreted as the amount of supers being excessive or insufficient.

Which is better – top- or bottom-supering?

Let’s get the science out of the way first.

There’s an assumption that bottom supering should be ‘better’ (in terms of honey yield) as it reduces the distance bees have to travel before they are relieved of their nectar.

A study conducted two decades ago by Jennifer Berry and Keith Delaplane {{4}} showed that – in terms of the amount of honey stored – it makes no statistical difference whether top- or bottom-supering is used.

This study was conducted at the University of Georgia (USA). It used 60 hives – 3 different apiaries each containing 10 hives over two distinct nectar flows.

Note the deliberate inclusion of the term ‘statistical’ above … the bottom-supered hives did end up with ~10% more honey in total but, considering the scale of the experiment, this was not statistically significant.

To determine if this difference was real you’d need to do a much larger scale experiment.

This was not simply weighing a few hives with the supers added on top or below … each colony used was balanced in terms of frames of brood, numbers of bees and levels of stores in the brood box for each nectar flow. That’s not my idea of fun when it would involve a few thousand colonies 🙁 {{5}}.

The Berry & Delaplane study reached the same conclusion as earlier research by Szabo and Sporns (1994) who were working in Alberta, Canada {{6}}. They had concluded that the failure to see a significant difference in terms of honey stored was because the nectar flows were rather poor. However, this seems unlikely as the Berry & Delaplane study covered two nectar flows, one of which was much stronger than the other (measured in terms of honey yield).

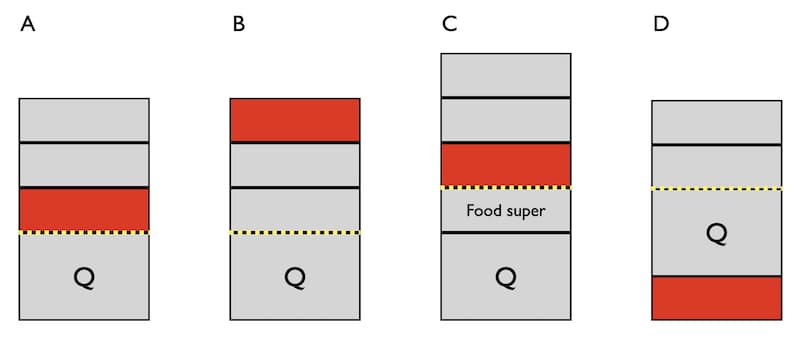

Before we leave the science there’s a minor additional detail to discuss about the Berry & Delaplane study. All their hives consisted of a single Langstroth brood box with a honey super on top underneath the queen excluder (refer to C. in the figure above).

This first honey super was termed the ‘food super’. The remaining supers were the ‘honey supers’. It’s not clear from the description in the paper whether the queen ever moved up to lay in the ‘food super’. I’m assuming she did not.

That being the case, the bottom supering employed by Berry & Delaplane is probably not quite the same as understood by most UK beekeepers.

When I talk about bottom-supering (here and elsewhere) I mean adding the super directly above the box that the queen is laying in (refer to A. in the figure above).

Whether ‘true’ bottom-supering leads to increased honey yields I’ll leave to someone much stronger than me. It’s an experiment that will involve a lot of lifting … and a lot of hives 😉

Which brings us to other benefits associated with where the super is added …

Benefits of bottom supering

I can think of two obvious ones.

The first is that the frames are immediately above the warmth of the broodnest. This might help get new foundation drawn a bit faster. However, if the flow is so good you’re piling the supers on it’s likely that the bees will draw comb for fun.

Note also the comments below about frame spacing and brace comb. I start new supers with 11 frames and subsequently reduce the number to 9. To avoid brace comb it’s easier to get undrawn supers built when there are no other supers on the hive. However, if that’s not possible I usually bottom-super them … it can’t do any harm.

The second benefit is that by bottom-supering the cappings on the lowest supers always stay pristine and white. This is important if you’re preparing cut comb honey. It’s surprising how stained the cappings get with the passage of hundreds of thousands of little feet as the foragers move up to unload their cargo in top-supered colonies.

Benefits of top supering

Generally I think these outweigh those of bottom-supering (but I don’t make cut comb honey and I’d expect the sale price of cut comb with bright white cappings trumps any of the benefits discussed below).

The first is that it’s a whole lot easier on your back 🙂

No need to remove the stack of supers first to slide another in at the bottom. This is a significant benefit … if the colony needs a fourth super there’s probably the best part of 50 kg of full/filling supers to remove first {{7}}.

Lifting lots of heavy supers is hard work. A decade ago I’d tackle three full supers at a time without an issue.

More recently, honey seems to be getting much denser 😉 … three full supers, particularly if on top of a double brood box, are usually split into two (or even three) for lifting.

Secondly, because top-supering is easier it’s therefore much quicker.

Pop the crownboard off, add another super, close up and move on.

Some claim an additional benefit is that you can determine whether the colony needs an additional super simply by lifting off the crownboard and having a peek. That might work with a single brood box and one super {{8}}, but it’s not possible on a double brood monster hive already topped with four supers {{9}}.

Of course, all of the benefits in terms of ease of addition and/or lack of lifting are null and void if you are going to be inspecting the colony and therefore removing the supers anyway.

Frame spacing in supers

Assuming a standard bee space between drawn, filled, capped honey stores, the more frames you have in the super the smaller the amount of honey the super will contain.

This might never be an issue for many beekeepers.

However, those that scale up to perhaps half a dozen hives soon realise that more frames per super means more time spent extracting.

That’s exactly what happened with me. My epiphany came when faced with about 18 supers containing almost 200 frames and a manual (hand cranked) three-frame extractor 🙁

By the next nectar flow I’d invested in an electric 9 frame radial extractor and started spacing my frames further apart.

That first ‘semi-automated’ honey harvest paid for the extractor and my physique became (just) slightly less Charles Atlas-like.

With undrawn foundation I start with a full box of 11 frames. However, once drawn I space the frames further apart, usually 9 per super. The bees draw out deeper comb and fill it perfectly happily … and I’ve got less frames to extract 🙂

I know some beekeepers use 8 frames in their supers. I struggle with this and usually find the bees draw brace comb or very uneven frames. This might be because our nectar flows aren’t strong enough, but I suspect I’ve spaced the frames too far apart in one go, rather than doing it gradually.

Frame alignment of supers

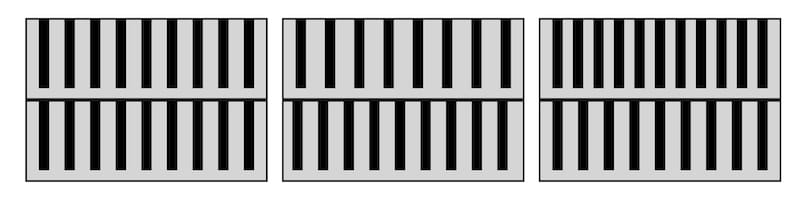

Speaking of brace comb … remember to observe the correct bee space in the supers. Adding a super with mismatched frame numbers will result in brace comb being built at the junction. The same thing happens if frames are misaligned.

Inevitably this brace comb ends up fusing the two supers together and causes a ‘right mess’ {{10}} when you eventually prize them apart.

And you’ll have to because they’re probably too heavy to lift together.

The example above is particularly bad due to the use of misaligned foundationless super frames. The comb is, as always, beautiful … and unusually in this example the bees built from the bottom upwards.

Note that the frame alignment between adjacent boxes does not appear to apply to the brood box and the first super. At least, it doesn’t when you’re using a queen excluder. I presume this is because the queen excluder acts as a sort of ‘false floor’. It disrupts the vertical bee space sufficiently that the bees don’t feel the need to build lots of brace comb.

You can use castellations to space the frames in the supers. I don’t (and got rid of my stock of used and unused castellations recently) as they prevent re-spacing the frames as needed {{11}}. The bees quickly propolise up the frame lugs meaning the frames are effectively immovable without the application of significant force.

Like with a hive tool … or if you drop the super 🙁 {{12}}.

Caring for out of use supers

After drawn brood comb, drawn supers are probably the most valuable resource a beekeeper has.

You can’t buy replacement so it makes sense to look after it.

Of course, having written the sentence above I realised I was almost certainly wrong. A quick Google search turned up this Bad Beekeeping post from Ron Miksha who described commercially (machine) produced drawn comb.

Three Langstroth-sized combs are €26 😯

There’s also this stuff …

OK, so I stand corrected. You can buy replacement drawn comb, but a single super will cost you about €78 {{13}} so they should be looked after.

Empty drawn supers should be stored somewhere bee, wasp and rodent-free. I store mine in a shed with a solid floor underneath the stack and a spare roof on top.

I have friends who wrap their supers in clingfilm … not 30 cm kitchen roll, but the metre wide stuff they use in airports to wrap suitcases {{14}}.

Wax moth infestation of drawn supers is generally not a problem. They much prefer used brood frames. However, it makes sense to try and make the stacks as insect-proof as possible.

Caring for in use supers

If the supers are full of bees and honey then the drawn comb is only the third most important thing in the box.

Don’t just pile the supers on the ground next to the hive. The lower edges of the frames will be festooned with bees which will get crushed. You’ll also pick up dirt from the ground which will then be transferred to the hive.

Instead, use an inverted roof. Stand the super(s) on it, angled so they’re supported just by the edges of the roof. This minimises the opportunities for bees to get squashed.

If you’re removing a stack of supers individually (because they’re too heavy to lift together) do not stack them up in a neat pile as you’re very likely to crush bees. It’s better to support the super on one edge, propped up against the edge/corner of the first super I removed.

Again, this minimises the chances of crushing bees. It’s distressing for the beekeeper, it’s definitely distressing for the bee(s) and it’s a potential route for disease transmission.

Once the supers are emptied of bees but full of capped honey you’ll need to transport them home from the apiary. I use spare Correx hive roofs to catch the inevitable drips that another more caring member of the household would otherwise discover 🙁

These Correx hive roofs aren’t strong enough to stack supers on. I always ensure there’s at least one or two conventional roofs in each apiary to act as temporary super stands during inspections.

Final thoughts

Tidy comb

At the end of the season it’s worth tidying the super frames before stacking them away for the year.

I use a hive tool to scrape off any bits of brace comb from the top and bottom bars of each frame. I also use a breadknife to level up the face of the comb. The combs are then arranged in boxes of nine and stored away for the winter.

A small amount of time invested on the supers saves time and effort doing much the same thing when you need them.

Drone foundation in supers

Over 50% of my supers are drawn from drone foundation.

There are two advantages to using drone foundation in the supers. The first is that there’s less wax and more honey; it takes less effort for the bees to build the comb in the first place and the larger cell volume stores more honey.

In addition, with less surface area in each cell, it’s at least theoretically possible to get a greater efficiency of extraction {{15}}.

The second benefit is that bees do not store pollen in drone comb. In a strong colony you sometimes get an arch of pollen stored in the bottom super, and this is avoided by using drone comb.

That doesn’t mean that they’ll necessarily fill the comb with nectar. Quite often they just leave an empty arch of cells above the brood nest 🙁

The major problem with using drone comb in the supers occurs when the queen gets above the queen excluder. You end up with my million drones fiasco and a lot of comb to melt down and recycle.

The super frame shuffle

Bees often draw and fill the central frames in the super before those at the sides. This can lead to very unevenly drawn comb (which can be ‘fixed’ with a breadknife as described above), and grossly unbalanced comb when extracting.

To avoid this simply shuffle the outer frames into the centre of the super and vice versa. The frames will be much more evenly filled.

Spares

If you have an out apiary, keep spare supers in an insect-proof stack in the apiary.

Alternatively, keep spares under the roof but over the crownboard. As a strong nectar flow tails off, or if the weather is changeable, it might save a trip back to base, or having to carry yet another thing on your rounds.

Note

I’ve now done the calculation … 11 National super frames have an area of ~5500 cm2 which would require 6.5 Langstroth-sized sheets of drawn commercial comb. At the prices quoted above (€26 for three) that would only cost about €56 … but you’d still have to slice’n’dice them into the frames.

Hmmm … almost 3000 words … not so short and sweet after all 🙁

{{1}}: Not least because I’m swamped with work and nucs and unmated queens and mated queens and keeping up with a spectacular nectar flow.

{{2}}: As an aside, note the date … 1840. This predates the development of Langstroth’s moveable-frame hive by over a decade. Thomas Wildman had described supering a skep-type hive in the late 1760’s that negated the need to kill the colony when harvesting honey.

{{3}}: Ask me again in the autumn, as that’s when it is usually relevant.

{{4}}: Berry, J. & Delaplane, K. Effects of top- versus bottom-supering on honey yield. ABJ May, 2000 pp. 409.

{{5}}: Considering the standard error of the experiment involving 60 colonies I think you’d need at least fifty times that number … however, be warned, stats is not really my speciality.

{{6}}: Szabo, T.I. & Sporns, P. A comparison of top and bottom supering on honey quantity and quality. ABJ 134:695-696 … note here that the title includes the word ‘quality’ which sounds a bit like Duncan’s ‘superior’.

{{7}}: And remember, you’ve probably done this when you added the second and third super as well.

{{8}}: Unless you’re ‘vertically challenged’.

{{9}}: Unless you’re freakishly tall … or take a stepladder to the apiary.

{{10}}: A beekeeping technical term that means ‘sticky and with lots of swearing’.

{{11}}: You can also buy frame spacing tools or use metal or plastic ends on the lugs – I’ve done neither so can’t comment on the benefits of these strategies.

{{12}}: Look carefully at the picture above and you’ll see that the super did have castellations. The photo was taken about 7 years ago. The super is an earlier incarnation by Denrosa/Swienty and contains no frame runners. I mended the super and it’s still in use today … what’s more, I bet those frames are still in use today as well.

{{13}}: It’s late and I can’t be bothered to do the calculation for the smaller amount of comb in a National super frame versus a Langstroth brood frame. And, even if I could, the prospect of joining together bits of drawn comb would take ages and be a real hassle. See also the note at the end of this post.

{{14}}: Or used to … maybe there’s a beekeeping sideline business opportunity there.

{{15}}: The most difficult honey to spin out of the cells is the last few bits adhering to the sidewalls of the cells.

Join the discussion ...