Summer doldrums

Maybe it’s old age {{1}} but the calendar seems to be speeding up these days. The dawn chorus is just a chirrup or two, there are mushrooms appearing everywhere, and I can sense the end of the season galloping towards me.

Or, maybe this is just a bit of a weird season.

It barely seems to have got started before it feels like it’s about to end.

The peak swarming period in my part(s) of Scotland has long gone {{2}} and the ‘June gap’ didn’t really happen, perhaps because the summer flowers started early. It’s now late July and the lime and blackberry are over. There’s some rosebay willow herb left, though not much and the heather has yet to properly start.

These are the summer doldrums; the time between the end of swarming and taking the summer honey off. It’s a relatively quiet time for my beekeeping. It’s too late (in Scotland, at least in my experience) for dependable queen rearing and it’s too early for any serious winter preparations.

There’s no longer a need to conduct weekly colony inspections. I’m reasonably confident that my colonies won’t swarm now, though I expect a few might supersede {{3}}.

That doesn’t mean they won’t swarm … it just means my confidence might be misplaced 😉 .

Of course, that doesn’t mean that there’s no beekeeping to do … it’s just that I’ve got a little more time to complete what I need to do, and a bit of spare time to do a few other related activities.

And, disappointingly, it looks as though the summer honey crop is going to be very poor this year, so perhaps this hiatus is effectively the end of the practical beekeeping season … 🙁 .

Weather watch

Beekeeping is greatly influenced by the weather. If it’s too cold the bees will not fly, if there’s a drought the nectar flow is likely to be disappointing, and if afternoon rain is predicted you’ll plan your inspections for the morning.

Most of my beekeeping is ‘coastal’ – I’m either influenced by easterlies coming in off the North Sea, or low pressure systems rolling in from the Atlantic. As a consequence, the weather can be ‘changeable’.

This often means wet and/or cool.

It’s not unusual to find my Fife east coast apiary blanketed in haar, while those further inland are 8°C warmer and bathed in sunshine. On the west coast the weather can change in minutes, from a balmy sunny morning to a claggy drizzle.

Dreich as it’s called in Scotland (apparently the ‘most popular Scots word’).

I therefore spend time planning things based on the (disappointingly spurious) predictions made by the weather apps on my phone.

My recent Fife trip predicted a wet morning followed by a dry and sunny afternoon with rain reappearing in the evening. I therefore planned to drive across in the morning, deliver honey when it was dry and then shift a bunch of nucs once the rain started (helpfully ensuring all the bees would be ‘at home’).

By mid-afternoon the rain was torrential as I carried increasingly soggy cardboard boxes full of jarred honey to the farm shops I supply.

The rain had stopped well before I got to the apiary to move the nucs and the bees were flying again.

Perfect … not.

Weather apps

I previously used the app Dark Sky for local weather forecasting. It seemed reasonably accurate and was particularly good at predicting what was likely to happen locally within the next hour or so. Unfortunately, Dark Sky was bought out by Apple in 2020 and killed off completely at the end of last year.

Apparently, some of the code was integrated into the Apple Weather app, but that’s little use to me as my phone is Android 🙁 .

I’ve therefore been reduced to using the BBC weather app and the one provided by the Met Office. The BBC predictions claim to be based upon Met Office data, but it’s not unusual for them to be wildly divergent from those made by the ‘official’ Met Office app.

Wildly divergent, but both wrong.

Of the two, the BBC app is more wrong and more often wrong. Not a commendable feature.

Neither are much good at providing accurate local weather predictions over short (hours) timescales.

As I carried those soggy cardboard boxes into the shop the BBC was still confidently showing a little white cloud icon with the sun peeking through behind it.

Useless.

If readers have a suggestion for a Dark Sky replacement (for Android) please leave a comment – it’s ‘hyper-local’ and short term predictions that most interest me. In the meantime, it turns out that the Apple Weatherkit API (essentially the code that accesses the underlying data) incorporates a lot of the Dark Sky functionality and is used by Android weather apps such as Real Weather, Forecaster and Weawow {{4}}.

Are these any use?

All of which was a slight digression …

Heather watch

The lime here was hopeless. I think it was warm, dry and calm enough for the bees to access it, and the trees to yield, on only a couple of days. The bramble has flowered well and it looks as though it will be a bumper year for blackberries {{5}} but the main summer/late summer nectar here is heather.

Having consulted the weather apps I ventured up the hills behind the house to have a look at how the heather is progressing. There is a bit in the ‘garden’, but it’s a lot more sheltered down here so doesn’t give a proper indication of how well it is likely to flower.

It was lovely to be out. The hills were quiet, only the plaintive calls of golden plover on the higher slopes could be heard over the wind. There were bachelor parties of stags, all with antlers still ‘in velvet’, up on the ridges. They’re all pals at the moment, but will be implacable enemies once the rut starts in 8-10 weeks.

Some patches of heather were in full flower, and busy with bumble bees, but a lot was still at least 7-10 days away from flowering. Disappointingly, almost as much looked dried up and withered, presumably after the protracted drought we had in May/June.

The moors here are unmanaged and the heather is mediocre to poor at the best of times. We never get those unbroken swathes of purple stretching to the horizon you see on the managed grouse moors … but I’d much prefer no muirburn, and the chance of seeing hen harriers and eagles, than a few extra supers of heather honey.

Inevitably, the rain I got caught in coming off the hill wasn’t predicted 🙁 .

Late season inspections

Colony inspections are less important once the chance of swarming is over.

How do I know it’s over?

Firstly because most of my colonies have been requeened and secondly because the weather and nectar flow have contrived to limit midsummer colony expansion.

I’m therefore inspecting once a fortnight now, and am unlikely to look through a box much after mid-August. I’ll still have to open them for feeding and treating, but I won’t be lifting many frames.

I keep some of my Fife bees in a friend’s garden. When I arrived on Monday he excitedly described the two swarms he’d seen in the intervening fortnight, one of which had occupied his chimney 🙁 .

Having apologised profusely and talked through the options I finally got round to opening some hives to review the ‘scene of the crime’.

I’d moved the nucs from this site the night before (without opening them) but was pretty confident none would have been strong enough to swarm … not least because the boxes felt disconcertingly light {{6}}.

All the hives had 2023 queens. Although it’s possible they could have swarmed, the queen wouldn’t have got far as she was clipped, so the bees would return to the hive. They would then have swarmed a bit later, perhaps when the virgin(s) emerged {{7}}.

Perhaps the first swarm my friend saw was with the clipped queen and the one 6 days later (that occupied the chimney) was headed by a virgin?

However, when I checked, all the hives had the clipped, marked queens I’d last seen a fortnight earlier.

Phew!

n+1 queens

But, it turned out, there were more queens than there were hives.

One of the boxes had an open queen cell on the central edge of a frame with a – very obviously – newly emerged virgin queen walking around on the comb. She was very large, very pale and very ‘furry’. The open cell still had the flap attached and I wouldn’t be surprised if she had emerged within the previous hour.

It was a fortnight since I’d opened the box. Time enough for them to start a cell from an egg, and for the queen to emerge.

However, the box also contained the queen I had expected to find there, and she was laying reasonably well, marching confidently {{8}} about being tended by her retinue of workers.

This looked like supersedure in action …

I could see nothing wrong with the ‘old’ queen. The brood pattern was good, the ratio of eggs to larvae to sealed brood looked about right, she was not being shunned or chivvied by the workers.

In circumstances like this I assume that the bees know best. There seems little point in pre-judging the outcome by culling one or other of the queens. When I next visit (early August) there may be two laying queens in the box.

I was relieved the bees in the chimney – and those dropping down the flue, covered in soot, onto the cream coloured carpet! – weren’t mine.

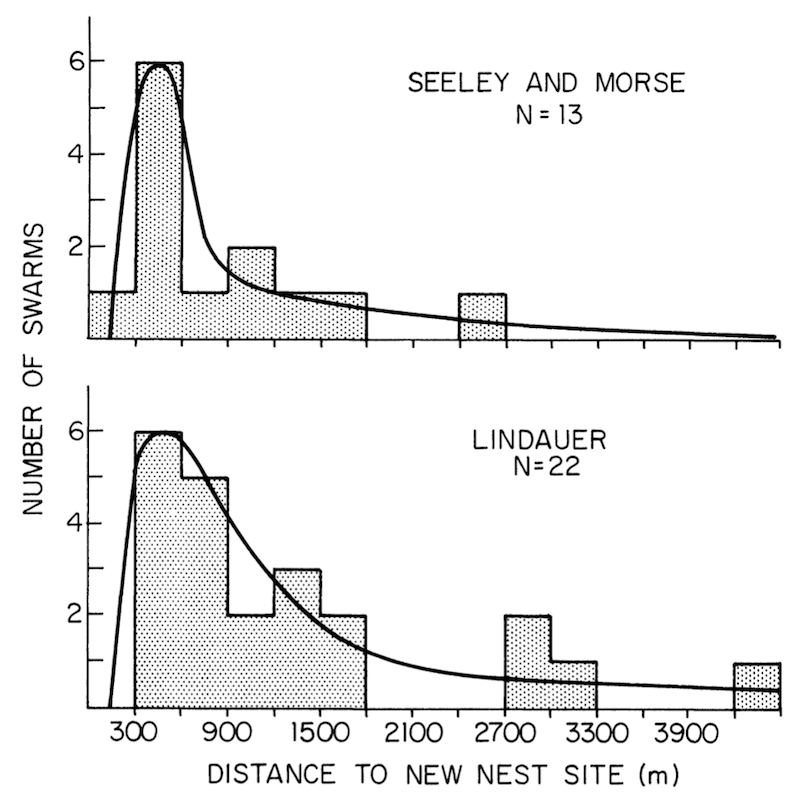

It’s worth remembering that several studies show that swarms relocate at least 300 metres when choosing a new nest site.

Unfortunately I’d had to piratize the bait hive from the apiary when I’d run out of brood boxes or the swarm may have ended up there rather than the chimney (and the carpet 🙁 ).

Managing nucs

I’m planning to overwinter several nucs. Most were prepared by harvesting a frame or two of brood in all stages from a strong colony and slipping in a mature queen cell, or a virgin queen I’d left to emerge in the incubator.

All but a couple now have mated queens.

Making nucs for overwintering, and then maintaining them through late summer and early autumn, can be a bit tricky.

The earlier you start them the more likely the queen will mate successfully. However, you then risk the rapidly expanding colony outgrowing the box … you can plan to overwinter a nuc and end up with a full colony.

Slightly better survival chances, but not ideal if you want to sell overwintered nucs 😉 .

Conversely, if you make the nucs up late there’s a chance the queen may not get successfully mated (and you have less time to check the brood she does produce) and you then risk laying workers developing, or have to unite the bees back with another colony.

I prefer to make the nucs early and then bleed brood off, using it to strengthen other colonies, so delaying swarming.

This requires reasonably careful judgement of the strength of the nucleus colony, the rate at which the queen is laying and keeping a watchful eye on the forage available and the weather.

I usually take a frame or two out, replacing it with foundation or drawn comb, whilst still ensuring there are sufficient stores in the box. It’s obviously a bit easier doing this with a six frame nuc box than a five framer.

If I get things right the size of the colony plateaus. As the weather cools I stop removing brood to ensure the nuc is very strong going into autumn.

Wax works

So, even this late in the season there’s still a need for a few new frames. What’s more, I’ve expanded my colony numbers on the west coast this year and so need a dozen more supers for the – inevitably crushingly disappointing {{9}} – heather harvest.

The frames aren’t a problem. In a recent clear-out of the shed I found hundreds of DN5’s and SN5’s I didn’t know I had 🙂 .

But no super foundation 🙁 .

The heather nectar flow is unlikely to be good enough for them to draw a box-full of comb on foundationless frames. In addition, I need some frames with foundation to interleave the foundationless frames or risk them drawing brace comb all over the place.

This is the first foundation I’ve bought for a year or three so was surprised at the price. Surprised as in shocked … there was nothing pleasant about it. Ten packets of premium foundation are the best part of £100.

Fortunately, the shed clear-out had also unearthed a box of extracted wax. It’s not high quality and it’s certainly not good enough for candle making, or furniture polish or – heaven forbid – soap.

But, conveniently, it happens to be almost exactly the right amount to trade for 100 sheets of premium super foundation 🙂 .

Which is what I did.

Wax extractors

With global warming solar wax extractors might seem like a tempting option. I built one years ago when I lived in the Midlands and it worked well … as long as I remembered to keep turning it to face the sun. However, it was too small and I was moving to Scotland (!), so it was abandoned, or repurposed.

I’ve also built a steam wax extractor. I butchered the metal side of a washing machine to make the floor of the extractor, probably one of the more dangerous DIY jobs I’ve completed {{10}}. It worked for several years, but always leaked – wax, water and steam – and, more recently, I gave in to temptation and bought one from Thorne’s.

It works well.

I can melt out 20 frames from one fill of the steam generator {{11}} and – importantly – at the time of the year I’m producing the frames (the beekeeping season) I can run the extractor late in the evening or on wet days (when there are no flying bees … and no sun).

I’m aware there are many other ways of recovering wax but I don’t produce enough to need oil drums and gas burners cluttering up the place when not in use.

I keep good wax – most brace comb, super frames etc. – and extract it separately. This stuff isn’t traded in. However, everything else gets chucked into the steamer and extracted. I then re-melt the wax with water in a slo-cooker, leaving it to settle and cool. The propolis and other rubbish sinks and can be scraped off the block to leave something that – whilst not being exactly pretty – can be traded for some shockingly expensive foundation 😉 .

And finally … a conundrum

The last colony I inspected on Monday had two supers over a single brood box. On lifting the supers off there were a couple of dozen drones – or, more accurately, drone corpses – wedged through the queen excluder.

The photo is misleading as I’ve turned the queen excluder upside down. These drones were attempting to go from the super into the brood box.

When I’ve seen this before it’s either because there are laying workers in the super or the queen had snuck above the excluder and the super frames were drawn on drone foundation.

But this colony has not been queenless and there was no sign of brood in the supers.

I’m perplexed … how did the drones get there? The supers are kept largely covered during inspections.

Answers on a postcard please …

{{1}}: Late middle age?!

{{2}}: Though some beekeepers are still losing swarms, see below.

{{3}}: Again, see below.

{{4}}: Which is a sufficiently stupid name I’m unlikely to try it.

{{5}}: Which will please our dog who loves them!

{{6}}: And were short on stores when I finally checked them.

{{7}}: It’s semantics, but is this a prime swarm or a cast? Prime means first/best, but also describes a swarm headed by a mated queen. Hmmm.

{{8}}: If you’ll excuse the anthropomorphising.

{{9}}: Crushingly … geddit?

{{10}}: Now, a decade later, the scar tissue is almost unnoticeable.

{{11}}: Mine, not the one Thorne’s sell.

Join the discussion ...