Stroppiness

Perhaps surprisingly this isn’t about some of the contributors to online beekeeping discussion forums … 😉 I’ll discuss those next winter when their “shack nasties” – and associated rantings – get really bad.

What beekeeping is

Beekeeping should be an enjoyable pastime. It’s a great way to work with nature, to learn and continue learning, to understand and interact with the environment … and to make delicious honey.

Of course, it’s lots of other things as well. It can be hard and hot physical work at times. It can be infuriating when the weather and the bees and a thousand other things conspire to frustrate your plans.

And in our long winters it can require a significant level of patience.

What beekeeping isn’t

What it isn’t, or at least what it shouldn’t be, is something that fills you with dread, that hurts like hell or that threatens, frightens or – even worse – harms other people.

All of these things can be the result of having aggressive bees.

You can and should do something to ‘cure’ the colony of its aggression.

Bees should not naturally be aggressive. When not threatened they go about their daily business in a workmanlike {{1}} way, collecting pollen or nectar or water. Unless inadvertently trapped in clothing or hair they almost never sting; when they do it’s because the bee is trying to defend itself.

Defensive bees can behave similarly to aggressive bees but they are not the same thing at all. In this case the ‘cure’ is very different and probably involves the beekeeper rather than the bees.

Colony management, aggression and defensiveness

Beekeeping involves managing the colony {{2}}. This necessitates regular inspections during the season.

It’s during inspections that both the nature of the colony and the abilities of the beekeeper are tested. It’s during these inspections that the beekeeper should try and distinguish between aggressive and defensive bees.

Aggression in bees is an unpleasant characteristic with predominantly genetic causes.

Defensive bees are reacting to a perceived threat and need to be treated more appropriately.

An aggressive colony

With little or no provocation, aggressive bees are out to get you. They buzz you a couple of times from yards away as you approach the hive, they ‘boil’ out of from under the crownboard when you gently prise it up, they bounce off your veil repeatedly or cling on tightly with the abdomen curled under them trying to sting.

They burrow into the folds in your beesuit, they worm their way under the cuffs of your gloves, they attack your hands and the hive tool as it is used to lift the frame.

And they don’t stop when you close everything up and thankfully retire. They follow you across the apiary and continue to bombard your (hopefully still veiled) head.

Truly psychotic bees follow you up the field back to the car. You have to hang around until they lose interest or drive off still wearing the veil {{3}}.

Before, during and/or after the inspection you’re getting stung. Depending upon the thickness of your gloves, your beesuit or your skin this might not hurt … but the build up of sting pheromone incites them even more. At worst, you’re forced to retreat from the onslaught.

It’s bad enough for the beekeeper. It’s much worse for anyone else inadvertently going near the colony, particularly after an inspection.

A defensive colony

A defensive colony is reactive rather than proactive. They react – in some of the ways described above – to rough treatment, to poorly timed interventions or to other perceived threats. They can and do sting, but if treated properly (i.e. better) they don’t.

A well behaved colony can become defensive if it is jarred, jolted or – and this has to be seen to be believed – dropped. Bees that should be perfectly calm and well tempered can ‘go postal’ if maltreated.

The significant difference here is that they’re being badly or poorly treated. This is where calmness, confidence and experience – or ideally, all three characteristics – shown by the beekeeper is the major influence on the behaviour of the colony.

An ideal place to observe this is in the training apiary of a large beekeeping association. With an experienced beekeeper the colony can be wonderfully well-tempered, barely stirring from the frames.

With an almost complete novice – who inevitably works slowly and remembers all of the good advice they were told in the theory lessons – the colony is also OK, though if the hive is open too long they can become a little tetchy.

But with the intermediate (in experience and ability) beekeeper, who knows just enough to be dangerous but who thinks they know it all, who squashes a few bees every time they drop a frame back into the hive, who crushes a few more as they lever the next frame up, who waves their hands to and fro over the top bars and who smokes the colony too heavily … to this beekeeper the colony can appear aggressive.

But they’re actually being defensive … because they’re being mistreated.

Going postal

Sometimes even the most experienced and careful beekeeper can have a D’oh! moment, instantaneously converting the calmest of colonies into a mushroom cloud-shaped maelstrom of psychotic bees.

I’ve seen an experienced beekeeper in a full training apiary inadvertently lift both a super and the brood box to which it was propolised off the floor. Once in mid-air the propolis gave way, dropping a full brood box onto the ground.

Kaboom!

I doubt there was a single beekeeper in the apiary over a 20 yard radius who wasn’t stung.

But these weren’t aggressive bees. They’d done nothing when the crownboard was removed. They were simply being defensive – understandably – once their home was dropped from a great height onto the ground.

The grey area between attack and defence …

I’ve been reasonably clear cut about the differences between aggressive and defensive bees. Overly so. There’s a grey area when an otherwise calm colony, almost irrespective of how well treated it is, can appear aggressive.

A number of “environmental factors” can influence the behaviour of the colony. The most important of these are forage, weather and queenlessness.

Bees are usually really well behaved when there’s a good flow of nectar. Open a colony when the OSR or lime is at it’s peak and you can do no wrong. Well, almost. However, open a colony when the OSR has recently gone over or the lime has stopped yielding and the bees can be a bit tetchy.

Short tempered perhaps, not truly aggressive.

Similarly, open a colony – or certain colonies – as the barometer plummets or there’s thunder rumbling in the near distance and they can also be rather short tempered.

In my experience most colonies get a bit stroppy when a strong nectar flow dries up. In contrast, only some overreact to poor weather. I have opened colonies during a thunderstorm – a long story, but it was to do with the day job long before we had the bee shed – and they were fine. In fact, they appeared to welcome the shelter provided from the rain as I stooped over the open box rummaging around for 2-3 day old larvae.

Finally, a queenless colony is usually more aggressive … or, perhaps more accurately, defensive. If the queenless colony does not rear a new queen it will fail.

Curing aggression

I don’t think aggressive bees should be tolerated. They make beekeeping a chore. Worse, they frighten passers by and terrify the mellisophobic {{4}}.

More worrying still is that aggressive bees might, either unprovoked or before calming down after an inspection, sting a passer-by who then goes into anaphylactic shock.

I don’t believe that aggressive bees are better at collecting honey, though many do.

Aggression is a genetic trait {{5}}. The only cure is therefore to change the genetics of the colony. This means culling the old queen and replacing her with a new one. If you haven’t got immediate access to a replacement queen I’d suggest culling the old queen and uniting the colony with a strong, well behaved, colony.

Often the behaviour improves quickly – presumably due to the different pheromones at work – but it’s worth remembering that it will be 6-9 weeks until all of the brood and workers originating from the old queen are replaced.

Curing defensiveness

Physician, heal thyself {{6}} … or, more correctly, Beekeeper, heal thyself. Since defensiveness is a reactive response to poor handling the best solution is to improve the quality and care of inspections. And possibly improve their timing as well.

Don’t inspect when the weather is poor and be particularly careful when a strong flow has recently stopped. Treat the hive and the colony gently. Use as little smoke as possible. Carefully remove one frame and set it aside. Break the propolis seal on the remaining frames, one side at a time, gently and without waving your hands over the box.

Remove and replace each frame without crushing bees under the frame lugs. Don’t crush bees between the side bars when pushing frames together. Don’t shake bees off the frames unless necessary.

Work reasonably quickly, carefully and confidently.

The bees will appreciate it.

Record keeping

When I inspect colonies, in addition to things like space, stores and queen cells, I’m also observing the behaviour of the colony. I record behavioural traits (temper, following and running on the frames) in my notes. Any colony consistently performing badly on these criteria is sooner or later requeened.

I can excuse one bad day. I can just about accept a second. But three weeks of poor temper – particularly if the other hives in the apiary are fine – and the monarch will be replaced {{7}}.

My notes from late last season showed that one very strong colony was developing aggressive tendencies. I couldn’t really face going through a double-brood box on a cool autumn day to find the old queen and unite the colony (and had no spare queens anyway).

The first inspection of the year has demonstrated they’re still a bit surly and, whilst not awful (no stings and no following), they’re probably only going to get worse as the colony builds up this spring.

If this shows any signs of happening I’ll unite the colony with another one – it’s too early in the season to have new queens and I’m not going to put up with bad behaviour.

Or impose it on passers by.

Colophon

Stroppy (and hence stroppiness) is probably derived from obstreperous and means ‘bad-tempered, rebellious, awkward, or unruly’. It’s a word that’s been in use since the early 1950’s.

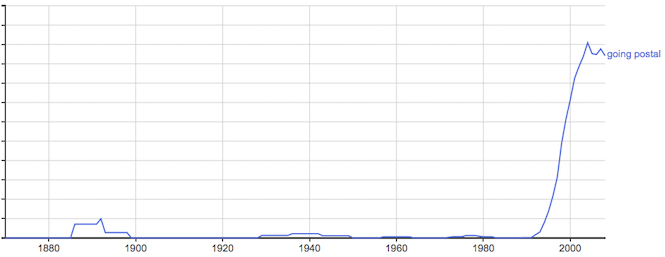

Going postal is a phrase that more specifically means stress-induced extreme violence. If you use Google’s ngram viewer to look the term up you’ll see that, other than a brief blip in the 1880’s, it’s a phrase only found in recent (>1990’s) English books.

Going postal has tragic origins as it refers to a spate of shootings in US post offices, by post office workers, in the late 80’s and early 90’s.

This post was timetabled to appear last week … major access issues with the website (repeated timeouts with visitor number reduced by about 40%) were repeatedly denied by my hosting provider and took them ~4 days to resolve, by which time I decided it was better to postpone posting. I got stroppy but didn’t need to go postal 😉

{{1}}: A clearly inappropriate term as the workers are all female.

{{2}}: Whatever the leave-alone “beekeepers” might suggest, this is a necessary component that helps ensure the keeping bit of beekeeping happens.

{{3}}: Following is one of the worst traits bees can have (in my opinion). Genetically it’s distinct from aggression as you can get aggressive bees that don’t follow. However, I’m not sure you can get bees that follow but aren’t aggressive … not least because following is itself a reasonably aggressive tendency.

{{4}}: Those with a fear of bees or bee stings, from the Greek μέλισσα, ‘melissa’ (honey bee) and φόβος, phobos (fear).

{{5}}: This is a UK-centric blog so I’m not going to confuse the issue here by also discussing ‘Africanized bees’ … these are the (in)famous ‘killer bee’ hybrids between A. m. scutellata and Italian or Ligustican strains which escaped quarantine in Brazil in the 1950’s and are inexorably spreading North … of course, the Africanization results in changing the genetics.

{{6}}: Luke 4:23 … a proverb meaning attend to one’s own defects rather than criticizing defects in others.

{{7}}: This assumes the colony isn’t queenless of course … under those circumstances I probably wouldn’t be inspecting them regularly to avoid interrupting a mating flight.

Join the discussion ...