Resistance is not futile

Amitraz-containing miticides are sold in the UK as Apivar and Apitraz.

Until recently they were only available with a veterinary prescription. I expect – though I have not yet seen data to support this – that their usage in the UK will increase now they are off-prescription. These miticides are now widely available and so there is greater opportunity to use – and misuse – them.

If you’re using Apivar {{1}} for the first time this year you will soon have to remove the strips from the hive.

That’s assuming you started treating early enough to protect the all-important winter bees from Varroa and its deadly viral payload.

This post is a reminder to remove the strips at the right time. The alternative – leaving them in place until the first Spring inspections – risks help the development of resistance to amitraz, so further reducing our opportunity to control mites effectively.

Leave and let die

Without careful integrated pest management (IPM) {{2}} Varroa levels build up in the hive. Varroa transmits viruses – most important of which is deformed wing virus (DWV) – to developing pupae. High levels of DWV either kills the pupa or results in emergence with or without significant developmental defects. Even those bees that are apparently normally developed have a reduced lifespan {{3}}.

Winter bees with a reduced lifespan prevent the colony from surviving through the winter until the queen starts laying again. I’ve also proposed recently that high levels of DWV, and the resulting increased rate of winter bee die-offs, probably accounts for some cases of isolation starvation.

So … intervention is needed to reduce mite levels, protect your bees and save your colonies.

Follow the instructions!

Apivar is one solution to reduce mite levels. It is an easy-to-apply chemical treatment that is very effective in reducing the Varroa load by ~95%. For a National hive it is applied as two polymer strips, each containing 500mg of slow-release Amitraz. Strips are hung between brood frames for 6-10 weeks and – for maximum efficacy – should be scratched with a hive tool and repositioned half way through the treatment period.

Unlike some other miticides (e.g. Apiguard and MAQS) there are no temperature restrictions for Apivar usage. The colony does not need to be broodless (a requirement for trickled oxalic acid-based treatments) as the treatment period covers multiple brood cycles.

Other than not using it with supers present the only contraindication for Apivar is to not use it if Amitraz-resistant mites are present.

How does resistance develop?

When discussing parasites and pathogens, resistance {{4}} is a consequence of two things:

- A selective pressure that kills the pathogen

- A population which exhibits genetic diversity

The selective pressure could be anything … heat for example, antibiotics prescribed by your GP, an antiviral against HIV or – of relevance here – Apivar against Varroa.

Killing – at the population level – is not absolute. Some individuals within the population survive longer than others. They could be exposed to a slightly lower dose, or be located in a protected niche for example. However, treat for long enough and the majority will be killed.

But there’s more …

Pathogen populations are not genetically invariant. Actually, many are quite diverse and have replication cycles that – deliberately {{5}} – generate diversity.

Therefore some pathogens are genetically slightly less resistant and some are genetically slightly more resistant to a selective pressure. We can ignore the former as they’ll rapidly be killed off … but we must be concerned about the more resistant ones.

Keep taking the pills

All of this is a ‘numbers game’, better represented with graphs and equations. However, the take-home message is simple … to effectively control a pathogen you need to treat for long enough and with a high enough dose to kill the vast majority of the population.

That’s why you’re encouraged to “complete the course” of antibiotics … or to remove the Apivar strips after 10 weeks and not leave them in over the winter.

Because both courses of action result in selection of more resistant pathogens.

If you stop taking antibiotics too soon, you won’t have treated for long enough and with a high enough dose. You end up selecting for the more genetically resistant pathogens.

Similarly, if you leave Apivar strips in overwinter you’ll be “treating” the remaining mites {{6}} with a lower dose of the miticide, which is an ideal situation to favour the growth of the slightly more genetically resistant mites.

How does Amitraz resistance develop?

Resistance to Amitraz in Varroa is well documented. It’s been described in a number of countries including the USA and Europe, Mexico and Argentina {{7}}. Generally resistance is defined in terms of a reduced level of mite killing, or – in laboratory experiments – an increased dose required to kill a certain proportion of mites.

However, I’m unaware of any studies defining the genetic basis of Amitraz resistance in Varroa.

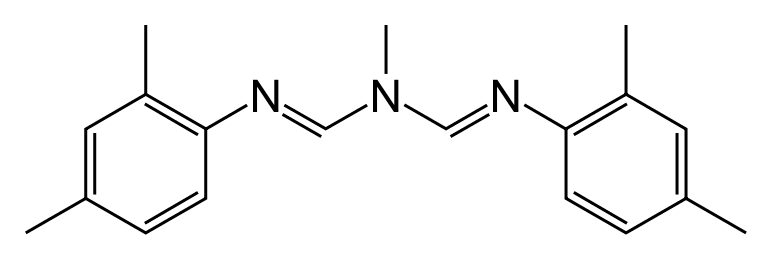

But Amitraz is a widely-used acaricide {{8}} and the genetic basis of resistance in cattle ticks is well understood. In these, ticks resistant to Amitraz carry a mutation in the RMβAOR gene {{9}}.

What {{10}} is the RMβAOR gene?

I’m glad you asked 😉

This gene encodes the β-adrenergic octopamine receptor protein and readers with good memories will recall that this is one of the targets that Amitraz binds to and inactivates {{11}}.

If the protein carries a mutation the Amitraz cannot bind to it and so the mite – or more correctly the tick as it’s yet to be formally demonstrated in mites – is therefore resistant.

(Bad) practical beekeeping

What does all this mean in terms of practical beekeeping?

It means use the correct number of Apivar strips for the colony and leave them in for the right length of time.

Do not …

- Use one strip on a full colony mid-season to ‘knock back the mites a bit’

- Re-use the strips in another colony (yes really!)

- Use improperly stored strips (or out of date strips) in which the effective Amitraz dose is reduced

I’ve heard examples of these types of misuse this season. All increase the chance of selecting for Amitraz-resitant mites.

And (the real reason for posting this at this time of year) …

- Do not leave the strips you added in late summer in the colony throughout the winter

Removing the strips takes seconds. Prize off the crownboard, grab the tab projecting above the top bars, gently withdraw the strip and close the hive up again.

Finally, because of the incestuous lifestyle {{12}} of Varroa the genetic diversity (and therefore potential presence of more resistant mites) in the population is likely to be increased by the high mite levels that prevail late in the season.

All the more reason to use the effective treatments we currently have in a way that helps ensure they remain effective.

Colophon

Resistance is futile

Resistance is futile is the title of a 2018 album by the Welsh rock band the Manic Street Preachers.

More specifically, in the context of this post, it was the phrase routinely used by the Borg – the alien cyborgs sharing a collective mind – in the Star Trek franchise. Borgs rarely speak, but when they do they usually include this phrase. For example “We are the Borg. Lower your shields and surrender your ships. We will add your biological and technological distinctiveness to our own. Your culture will adapt to service us. Resistance is futile.” The warning about resistance being futile was usually accompanied by the threat that the target would be “assimilated”.

I’d started writing this post using the title ‘Resistance is futile’ but realised late on that – as far as Varroa are concerned – resistance is anything but futile {{13}}.

Resistance – to miticides – gives Varroa a reason to live. Literally.

Let’s not help them 🙂

{{1}}: I’ll use Amitraz, Apivar and Apitraz interchangeably in this article. The active ingredient is the same, the instructions for use are broadly the same and the potential for the development of resistance is therefore similar.

{{2}}: Which might involve a combination of hard and soft miticides and a variety of interventionist beekeeping practices to reduce mite levels.

{{3}}: Amongst a number of other defects.

{{4}}: Which in this context almost always means resistance to being killed or inactivated.

{{5}}: By which I mean that there’s evolutionary selection for a replication strategy that produces diversity.

{{6}}: And there will be remaining mites, as the initial treatment is only ~95% effective.

{{7}}: For example, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00436-010-1986-8 and https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00218839.2005.11101162?journalCode=tjar20.

{{8}}: A substance poisonous to mites or ticks.

{{9}}: Corley et al., (2013) Mutation in the RmβAOR gene is associated with amitraz resistance in the cattle tick Rhipicephalus microplus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110:16772–16777)

{{10}}: Or perhaps WTF?

{{11}}: Formally this is a circular argument built upon the premise that resistance is associated with a mutation in this gene. The real proof of the pudding will require binding studies to be undertaken with Amitraz and the RMβAOR protein to show both inactivation in vitro and a reduced interaction with the mutant protein. These are not trivial studies for a variety of reasons. Don’t hold your breath.

{{12}}: Literally … I’ll discuss this in the future sometime.

{{13}}: Defined as ‘incapable of producing any useful result’ or ‘pointless’.

Join the discussion ...