Queen introduction

I’m probably less qualified to write about queen introduction than almost any other aspect of beekeeping. This is not because I’ve not introduced any queens. Quite the opposite, it’s something I do more or less routinely many times a season.

The reason(s) I’m really not qualified to discuss the topic are:

- I almost exclusively use the method I first used and I’ve not done any side-by-side comparisons with other methods to determine which work ‘best’. I have a method that works well enough i.e. somewhere between most of the time and almost always. That’s good enough for me.

- I’m not aware of any recent scientific studies on the subject so cannot use those to make informed decisions – or interpretations – of why some methods work and others don’t {{1}}.

Nevertheless, not being qualified has never stopped me before {{2}} and it’s a topic that some beekeepers struggle with and many beekeepers worry about.

So here goes …

Art or science?

David Cushman/Roger Patterson make the point that:

” … you can have two colonies in the same condition, in the same apiary, on the same day and if you introduce a queen in the same condition into each, one will succeed and the other will fail.”

This doesn’t mean that 50% of introductions fail (although it reads that way). What he/they mean is that there appears to be no rhyme or reason why one succeeds and the other does not.

On another day, both might succeed … or both might fail 🙁

Is it therefore an art or a science?

I don’t know. All you can do is get the basics correct and cross your fingers …

For understandable reasons, beekeepers feel rather precious about their queens. In particular, beekeepers who do not rear their own queens (and so have no spares waiting in the wings) can get a bit paranoid about queen introduction.

What if it goes wrong?

The colony will potentially be left irretrievably queenless and – if you purchased the queen – you’ll be £40 out-of-pocket {{3}}.

If you do rear your own queens you can perhaps be a bit more blasé about queen introductions. Potentially you can also do the sort of side-by-side comparisons I mentioned above … though there aren’t many studies where this has been done in a rigorous way.

Most seem to find a method that works for them and then stick with it … which is what I’ve done and what I’m going to describe.

This is what I mean by ‘get the basics correct’.

I’ll also mention an alternate method I irregularly use for what I consider to be really difficult situations and/or really valuable queens.

But before we get into the methodology, it’s worth making some general comments about the state of the recipient colony and the queen being introduced.

Is the colony really queenless?

Trying to introduce a new queen into a colony that is not actually queenless will not end well.

One or both of the queens will probably not survive the experience. Either the workers will reject (and slaughter) the incoming queen, or the queens will fight and may both be damaged and lost.

It is therefore important that the recipient colony is queenless.

By queenless I mean that there is no queen present.

I do not mean no laying queen present. If you try and introduce a new queen into a colony with a failed (non laying) queen or a virgin (unmated) queen you will have problems.

Sod’s Law is explicit in these instances … the valuable new mated laying queen will be lost 🙁

The very best way to be sure the colony is queenless is to remove the current queen before introducing the new one. That necessitates finding the queen in the first place.

What if you can’t find the queen but you’re sure that the colony is queenless?

Well, there are only two possibilities if you can’t find the queen, these are:

- The colony is queenless … you’re good to go.

- The colony is not queenless … but you’ve looked so hard for so long they’re now disturbed and running manically around the frames, getting more and more agitated and angry. Neither the bees or you are any sort of state to allow the queen to be discovered. Close the hive up. Have a cup of tea. Try again tomorrow.

I discussed methods of determining whether the colony is queenright (though not by extrapolation, the opposite i.e. queenless – see below) last season. Towards the end of that post I described the addition of a ‘frame of eggs’ to determine if the colony is queenright or not. I won’t repeat all the details here.

If the colony draw queen cells on the introduced frame then you can be sure that the colony is queenless. See (1) above … you’re good to go 🙂

Not queenless, but not queenright

That same post describes the concepts of queenright and queenless.

A colony that is queenright has a mated queen capable of laying fertilised eggs (though she may temporarily not be laying, for example due to a dearth of nectar).

A queenless colony contains no queen.

But there’s an intermediate stage … or potentially two intermediate stages if you allow me a little leeway.

A colony containing a failed queen that’s either not laying at all (and not going to restart), or only laying drone (unfertilised) eggs is neither queenright not queenless. This colony will not draw queen cells on the introduced frame. You cannot safely introduce a new queen into such a colony before first finding and removing the failed queen.

A colony containing laying workers will also not {{4}} produce queen cells from the introduced frame of eggs.

A colony with laying workers behaves as though it’s queenright but is actually queenless. It’s not really an intermediate stage, but the consequences are the same. Again, they are highly unlikely to accept an introduced queen.

Deal with the laying workers first and then requeen … and good luck, laying workers can be a nightmare 🙁

OK … let’s assume the colony really is queenless … what’s the easiest way to introduce a new queen?

Add a sealed queen cell

Almost without exception, a queenless colony can be requeened by adding a sealed queen cell. The virgin queen will emerge, go on one or two mating flights and return and head the colony. This method of queen introduction is almost foolproof in my experience.

Where do you get the queen cell from? Another colony, your mentor, a friend in your beekeeping association, a local queen rearer … necessity is the mother of invention {{5}}.

Assuming the cell is a natural queen cell … cut the queen cell out of the comb with a generous amount of surrounding comb. Don’t risk damaging the queen cell. Keep it vertical … there are stages during development when the pupa is susceptible to damage. Ideally choose and use a cell 24-48 hours from emergence as they’re a lot more robust late in the development cycle.

Use your thumb to make an indentation towards the top of a frame near the centre of the broodnest, above some capped and emerging brood. Using the generous ‘edge’ of comb surrounding your chosen queen cell push this into the indentation so the cell is secure. Close up the colony and a) check for emergence in 48 hours or so {{6}} and b) a fortnight later for successful mating.

If the cell is from a grafted larvae it is even easier … press the plastic cell cup holder into the comb and push the frames together. I describe this in a recent discussion of grafting.

How successful is this method of ‘queen’ introduction?

I’d estimate at least 85%.

A very small percentage of queen cells fail to emerge (or rather, the queen fails to emerge from the cell … but you knew what I meant 😉 ).

A slightly larger percentage of queens fail to mate (or fail to return from a mating flight). But, even in a bad season, it’s rarely more than 10-15%.

The new queen is accepted by the colony because she emerged there and they all live happily ever after 😉 .

What?

I know, I know … that’s not really queen introduction.

You’re right. But it works. Very well.

These are the two methods I use for queen introduction.

Candy-plugged queen cage

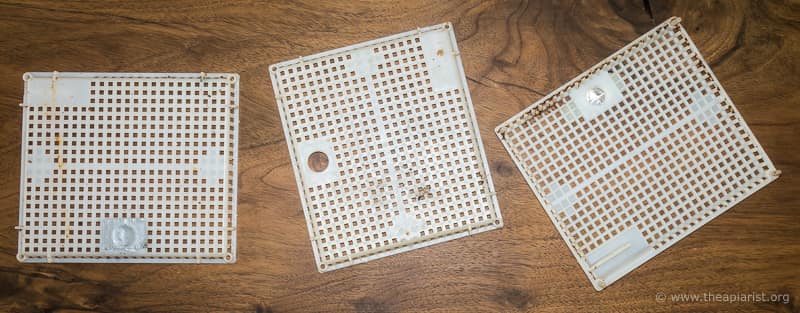

I have a large supply {{7}} of JzBz queen introduction and shipping cages.

I really like them because they were free they are reusable, they have a tube-like entrance that can be plugged with candy/fondant and they have a central region to protect the queen from aggressive workers outside the cage.

Some cages offer no areas of refuge for the queen and workers can damage the queen through the perforations. Avoid cages that are all perforations.

The JzBz cages can be purchased with a removable plastic cap (shown below the cage in the image). These fit over the end of the tube and can seal the cage until you judge the colony is likely to gracefully receive the new queen … as described below {{8}}.

Using a JzBz cage for queen introduction:

- Plug the tube of the JzBz cage with queen candy or fondant. Queen candy can be purchased commercially and kept frozen for long periods. I almost always use fondant these days as I have spare boxes of the stuff from autumn feeding.

- Add a short piece of wire or a cocktail stick through the perforations at one end of the cage to hang the cage – entrance tube pointing downwards – between two frames. Do this before adding the queen to avoid risking skewering the queen at a later stage {{9}}.

- Place the queen in the cage without any attendants (see below for comments on removing them). Close and seal the cage. Seal the candy tube with the plastic cap.

- Hang the cage in the centre of the broodnest, above some emerging brood. Leave the colony for 24 hours.

The idea here is that the colony gets the chance to accept the new queen without getting the opportunity to slaughter her.

Look for signs of aggression

Colonies that have been queenless for a few hours (say 2-24) before adding the new queen are usually very willing to accept a replacement. Adding a queen immediately after removing the old queen is likely to result in some aggression to the caged queen.

Check the colony after 24 hours. I usually lift the cage out and place it gently on the top bars to observe the interaction of the workers and the queen.

If the colony show no aggression to the caged queen – look for bees trying to sting through the cage or biting at the cage – then remove the plastic cap and re-hang the cage between the frames.

If they show aggression leave them another 24 hours and check again {{10}}.

Once you remove the cap the queen will be released by the workers after they eat through the candy/fondant. This takes just a few hours.

Check again a week later to ensure the colony has accepted the queen.

Nicot introduction cage

I use the method described above for almost every queen I introduce.

The only exception is if I have to requeen a colony that has previously not accepted a queen using the method described above. Usually such a colony will also be broodless (just based on the timings of determining they are queenless and failing once to successfully introduce a queen).

Under these circumstances I use a Nicot queen introduction cage.

I find a frame from another colony with a hand-sized patch of emerging brood. The comb needs to be level so that the cage can sit on top without gaps for the queen to escape.

Then do the following:

- Remove all the bees from the frame and place the Nicot cage over the brood using the short plastic ‘legs’ to hold it into the comb {{11}}.

- Secure the cage in place using one or two elastic bands.

- Introduce the queen through the removable – and eminently losable {{12}} – door.

In practice it’s easier to do this in the order 3-1-2 … place the queen on the frame, cover with the cage and then secure it with the elastic band.

Add the frame and cage to the hive, locating it centrally. Push the frames together.

The emerging workers will immediately accept the queen and feed her. Other workers will feed the queen through the edges of the cage.

One corner of the cage has an entrance tunnel that can be filled with candy/fondant. I don’t think I’ve ever used this. In my experience the colony releases the queen by burrowing under one edge of the cage after a few days. If they don’t, check and remove the cage a week later.

I don’t think I’ve ever failed to successfully introduce a queen using one of these cages, but it’s a relatively small sample size.

Thorne’s sell a metal mesh version of this cage that has integral ‘legs’. I’ve not used it, but the principle is the same. Keep it in a box or the sharp cut metal edges will butcher your fingers – it’s difficult picking up queens with heavily bandaged digits.

You could also ‘fold’ your own from mesh floor material. One with deeper ‘sides’ could be pushed down to the midrib of the comb, so reducing the chances of the bees burrowing under the edge of the cage.

Mated or virgin?

I use the JzBz cage for introducing either mated or virgin queens. I’m not aware of any significant difference in the acceptance rate between them.

However, it’s worth noting that acceptance is dependent upon essentially ‘matching’ the expectations of the colony with the state of the queen.

A virgin queen will be less likely to be accepted by a colony from which a mated laying queen has recently been removed. Leave them 24-48 hours.

Likewise, I remove nearly mature queen cells from a colony I’m requeening with a mated queen. I don’t want to risk an early-emerged virgin queen from ‘raining on the parade’ of the introduced queen.

I’ve only used the Nicot cage for mated queens. Since the latter is usually used for a broodless colony I want the minimum possible delay before there is new brood in the colony.

Alone or with attendants?

If you purchase a queen and receive her by post there will be a few workers caged with her.

I always remove these although some suggest that they do not adversely influence acceptance rates {{13}}. I remove them because I’m a bit paranoid about viruses … these workers come from an ‘unknown’ hive (quite possibly not the same one that the queen came from) and will carry a potentially novel range of Deformed wing virus variants (and possibly others as well).

I don’t want these in my hive so I remove the workers

It’s also worth noting that Wyatt Mangum has an interesting report in American Bee Journal indicating that the presence of attendants significantly increases the acceptance time {{14}} for an introduced queen {{15}}. In some cases the presence of attendants resulted in the colony showing aggression for longer than it took for the bees to eat through the candy plug … that’s not going to end well for the queen.

The safest way to remove attendants is to open the caged queen in a dim room with a single closed window. The bees will fly to the window (perhaps with a little encouragement).

A mated queen probably will not fly at all and can be re-caged. A virgin queen can fly well and will also end up at the window. Gently grab her by her wings and re-cage her.

You can do all this in the apiary … it requires confidence and dexterity. I know this because I recently tried it with a virgin queen in my apiary, using lashings of overconfidence and hamfistedness.

She flew away 🙁

Inevitably you can buy a gadget to help you with this – the queen muff.

Conclusions

There is always a slight risk that queen introductions will not be successful. The queen pheromones have such a fundamental role in colony maintenance that disrupting them – or suddenly changing them – may lead to rejection.

However, the methods described above are sufficiently successful that I’ve not found the need to look for better alternatives. They’re also sufficiently fast that I’m not tempted to try some of the ‘quick and dirty’ approaches {{16}} to save time.

Finally, it’s worth noting that it is usually easier to requeen a nucleus colony than a full hive. If I ever bought one of those €500 breeder queens I’d introduce her to a nuc first and then unite the nuc back with the original colony.

But that’s not going to happen 😉

{{1}}: The best source of comparative assessments is probably the ‘old’ beekeeping literature like Snelgrove or Laidlaw, though they are often not properly controlled studies. There are scientific studies of queen introduction, but they tend to be methodological, rather than explaining why certain methods work when others do not. For starters perhaps try Szabo T.I. (1977) Behavioural studies of queen introduction in the honey bee. VI. Multiple queen introduction, J. Apic. Res. 16, 65–83 and the other papers in this series.

{{2}}: My only beekeeping qualification is the BBKA ‘Basic’ and my dislike of examinations – having done too many during my training and set/marked too many in academia – means I’m unlikely to do any more.

{{3}}: Or €500 …

{{4}}: Or at least not dependably in my experience … it seems to depend upon the proportion of laying workers, or how long the colony has had laying workers in it.

{{5}}: But I can guarantee that the offer of a bottle of good red wine will make this task much easier.

{{6}}: Late in the day … don’t risk disturbing an orientation or mating flight by the virgin queen. Just check the cell has been vacated. You do not need to find the virgin queen.

{{7}}: Literally a bucket load I was generously given several years ago.

{{8}}: The fork-like spike thingy attached to the cap is to hang the cage from the comb. You remove it and push it into the ‘top’ of the cage – see the first picture in this post. I’ve not used these for about 5 years and instead leave them attached to the cap to help me find the caps in the bee bag.

{{9}}: Don’t ask. Just don’t ask.

{{10}}: And, if necessary, repeat again … and if they continue to show aggression it’s likely the colony is not queenless.

{{11}}: The ‘legs’ are easily lost or broken. Use half matchsticks as replacements

{{12}}: Most of mine are replaced with a piece of tape with the sticky side covered to avoid gluing the queen to the door!

{{13}}: See McCutcheon D. (2001) Queen introduction, Bee World 82, 5–21.

{{14}}: The time before the colony stops showing aggression to the new queen.

{{15}}: Mangum W. (2020) Queen introduction Part 2: The effect of attendant bees. ABJ 160(7):763.

{{16}}: Like the smoke and shake methods e.g. smoke the colony well and dump the bees and the queen at the hive entrance … no thanks!

Join the discussion ...