Ouch, that hurt

If you keep bees you’ll inevitably get stung.

Not necessarily often and not necessarily badly, but getting stung goes with the territory.

You’ll probably get stung more often if your bees are stroppy, or if you are clumsy. But even if you’re careful and the bees are calm there’s always the chance of being stung.

I moved a very feisty colony late one evening last week {{1}}. The hive was sealed, moved and re-located to an out apiary. Knowing they were, er, rather temperamental I let them settle for 15 minutes, then gently lifted the entrance block.

Out they boiled … as I beat a very hasty retreat 🙁

I thought I’d got away with it, but driving home 20 minutes later I was stung on the ankle by a stowaway in my boot.

Ouch! That hurt.

I’ve only been stung a few times all season. Most didn’t hurt much at the time and were forgotten within minutes. That sting on the ankle hurt like hell and was sore for a further 48 hours.

Why does it hurt when you’re stung? Furthermore, assuming stings are inevitable, which parts of the body hurt more when stung … and so deserve additional protection?

Why do bee stings hurt?

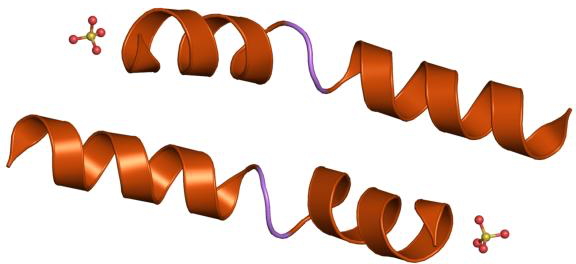

The honey bee sting is a hollow barbed tube used to deliver the venom. About 50% of bee venom by weight is the small protein mellitin.

It’s fair to say that mellitin is small but potent. It’s only 26 amino acids {{2}} long and forms a tetramer in aqueous solution. The ‘noughts and crosses’ shape it adopts hides the hydrophobic parts of the peptide and therefore allows it to ‘dissolve’ in venom. However, the tetramer dissociates at or near cell membranes into which monomeric mellitin embeds itself.

And this is where the pain and damage start …

Membrane-association causes cell lysis {{3}}. This results in the release of all sorts of cytokines from the cells which signal ‘damage’ to the body, leading to the inflammatory response usually associated with bee stings. That’s the long-term effect of a bee sting. However, simultaneously, mellitin triggers the expression of proteins known as sodium channels in pain receptor cells. These allow large amounts of sodium to flow across the membrane. It is this that is directly responsible for the pain sensation when you are stung.

So, if being stung is almost inevitable and if bees have evolved stings to cause pain (which they have), in which parts of the body is the pain sensation most marked?

Measuring pain

Pain is a subjective response. What’s painful to me might hardly be noticed by someone with a higher pain threshold. Two individuals receiving the same sensory input can experience very different sensory responses {{4}}.

As an aside it’s well documented that there are differences in the pain felt by males and females {{5}}. All the pain reported in this article is from studies – or personal experience – by males.

Therefore, to meaningfully determine how much pain a sting causes, from a particular insect or at a particular location for example, it’s essential that the studies are properly controlled. This includes taking account of variation between individuals and variation within an individual on a day to day basis.

These are not the sorts of studies that attract large numbers of volunteers 😉

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the scientific work in this field is often published in single author papers in which the author alone is the ‘volunteer’.

The Schmidt Sting Pain Index

Before discussing honey bees specifically a brief diversion must be made to introduce the seminal studies by Justin Schmidt.

Schmidt is an entomologist at the Carl Hayden Bee Research Centre in Arizona. He’s interested in haemolysis (the cell lysis caused by mellitin and other constituents of insect venom) and whether the evolution of sociality in hymenopterans (bees, ant and wasps) required the evolution of toxic and painful stings.

Over about twenty years Justin Schmidt published a number of papers on hymenopteran venoms and the pain that they cause. In his early papers he rated stings on a scale of 1 – 4 (actually 0 upwards, but 0 was totally painless to humans).

Only a very few insects scored 4, including bullet ants about which Schmidt comments “Paraponera clavata stings induced immediate, excruciating pain and numbness to pencil-point pressure, as well as trembling in the form of a totally uncontrollable urge to shake the affected part“.

You can’t fault his commitment, but you might question his sanity.

Schmidt published his magnum opus in 1990 in which he ranked stings by 78 hymenopteran species covering 41 genera {{6}}. His descriptions of the pain induced are often entertaining. The aforementioned bullet ant is “pure, intense, brilliant pain…like walking over flaming charcoal with a three-inch nail embedded in your heel“.

Another sting scoring 4, that of Synoeca septentrionalis (the warrior wasp) is accompanied by the statement “Torture. You are chained in the flow of an active volcano. Why did I start this list?”.

Why indeed?

Standing on the shoulders of giants

Bees and wasps scored 2 on the Schmidt Sting Pain Index. What Schmidt didn’t investigate was the influence of the location of the sting on the pain experienced.

Which brings me to Michael Smith. In 2014 Smith published an entertaining paper entitled Honey bee sting pain index by body location. It’s published in the journal PeerJ and the full paper is available for download.

It’s a well controlled study written in an engaging style that most readers will appreciate.

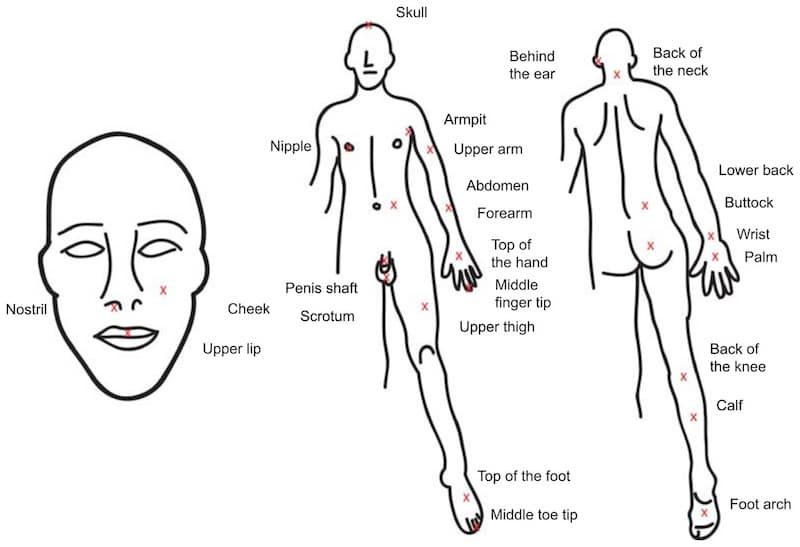

Building on the landmark studies by Schmidt, Michael Smith rated the pain endured from honey bee stings in 25 different locations.

Some of these locations should really be protected with a bee suit.

Smith controlled the study by always including an “internal control” i.e. comparing two test locations with three stings to his forearm.

Every time.

All locations were tested in triplicate (randomly). This meant that Smith was stung a minimum of five times for 38 consecutive days. Ouch.

There are some excellent quotes in the paper … “Some locations required the use of a mirror and an erect posture during stinging (e.g., buttocks)“. Scientists involved in studies that require ethical approval will appreciate the comments made in the paper on self-experimentation.

And the results? To quote directly from the paper “The three least painful locations were the skull, middle toe tip, and upper arm (all scoring a 2.3). The three most painful locations were the nostril, upper lip, and penis shaft (9.0, 8.7, and 7.3, respectively)” {{7}}. Interestingly, skin thickness did not correlate with the pain experienced.

My experience of stings is limited. Those I’ve had to the face (including the lower lip) have been relatively painless, but the subsequent inflammatory response has been dramatic. Smith only scored immediate pain … I think a follow-up study on inflammation and its duration is needed.

I’m not going to conduct it.

Points pain means prizes

You can’t fault the dedication shown by Justin Schmidt and Michael Smith {{8}}. That sort of dedication should be recognised with prizes and honours.

And it was.

Schmidt and Smith shared the 2015 Ig Nobel prize for Physiology and Entomology. The Ig Nobels – a parody of the Nobel prizes – recognise unusual or trivial achievements in scientific research.

The list of Ig Nobel prizes awarded is eclectic and highly entertaining … Medicine (2013) “for treating “uncontrollable” nosebleeds, using the method of nasal-packing-with-strips-of-cured-pork“, Economics (2005) for the inventors of “Clocky, an alarm clock that runs away and hides, repeatedly, thus ensuring that people get out of bed, and thus theoretically adding many productive hours to the workday” and Psychology (1995) for “their success in training pigeons to discriminate between the paintings of Picasso and those of Monet” {{9}}.

Sir Andre Geim received the Physics Ig Nobel in 2000 for levitating a frog by magnetism. Yes, really. Ten years later he was awarded the Nobel prize in Physics for his studies on graphene. He’s the only holder of a Nobel and Ig Nobel.

Marc Abrahams, the founder of the Ig Nobel awards, regularly tours giving talks on Improbable Research and the Ig Nobel prizes.

Go if you get the chance … it’s highly entertaining.

{{1}}: Not my own bees I’ll hasten to add. They originated from a reader of this website who shall remain nameless. Suffice to say the bees are borderline psychotic … and worse on a cool, autumn evening with a few spots of rain in the air. Unfortunately, because they’re part of an experiment, the colony cannot be re-queened until next year … or treated with petrol.

{{2}}: The ‘building blocks’ of proteins.

{{4}}: Coghill R.C. (2010) Individual Differences in the Subjective Experience of Pain: New Insights into Mechanisms and Models. Headache 50:1531-35.

{{5}}: Sex differences in pain: a brief review of clinical and experimental findings

{{6}}: Schmidt, Justin O. (1990). “Hymenoptera Venoms: Striving Toward the Ultimate Defense Against Vertebrates”. In D. L. Evans; J. O. Schmidt. Insect Defenses: Adaptive Mechanisms and Strategies of Prey and Predators. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 387–419

{{7}}: Which is not something I’d ever expected to write in this blog!

{{8}}: Or Christopher Starr who extended the original studies by Schmidt … Starr, C.K. (1985). “A simple pain scale for field comparison of Hymenopteran stings” (PDF). Journal of Entomological Science. 20 (2): 225–231.

{{9}}: This is something that bees can do as well which I’ll discuss sometime in the future.

Join the discussion ...