A no competition, competition

Unless you’re in an unseasonably warm part of the country, mid-April is usually early enough to put out your bait hives. This year, because of the unusually cold snap in the last week or so, it might still be a bit early. However, colonies are developing well and as soon as the weather properly warms up they will start thinking about swarming.

Regular readers, look away now

I’ve written a lot about bait hives in previous years. Anyone who assiduously follows this site and – unlike me 😉 – remembers what’s been written before can skip ahead to the next section.

But for those who need an aide memoire …

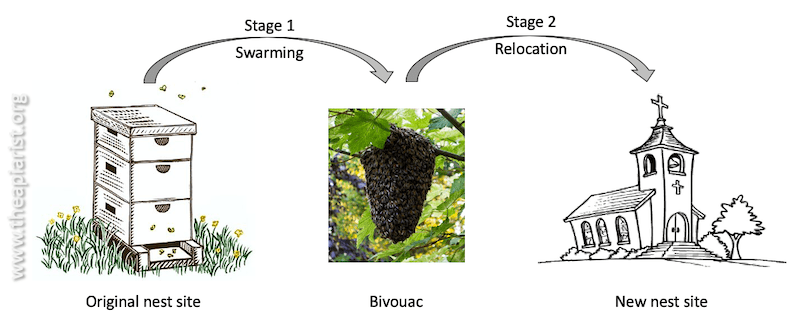

The purpose of a bait hive is to attract a swarm that you (surely not?) or someone else has temporarily misplaced i.e. lost {{1}}. When a colony swarms it settles in a temporary bivouac from which the scout bees fly to survey the area for a suitable new nest site.

The scout bees have very particular requirements.

They’re looking for cavities of about 40 litres volume with a small, clearly visible, south facing, entrance near the base.

Evolution and fussy house hunters

Bees have evolved to nest in trees – not quaint cartoon churches as shown above – and cavities in trees come in all shapes and sizes.

This is why they don’t care what shape the cavity is. However, cavities with small entrances are easier to defend, which is why they prefer them {{2}}.

In addition, bees favour cavities situated more than 5 metres above ground level. Again, this makes evolutionary sense. It’s not just Winnie the Pooh that likes honey. The higher up a tree they nest, the less likely they would be detected by a bear {{3}} on the ground. And if the nest remains undetected (or unreachable by a climbing bear) there’s a chance the colony will thrive and reproduce (swarm) to pass on the ‘high altitude’ nest site preference gene.

And if you’ve evolved to nest in a tree cavity in a wood filled with other trees, it again makes evolutionary sense for the entrance to be clearly visible. If it wasn’t, bees on their orientation flights would inevitably get confused (and therefore lost).

Finally, bees have a strong preference for cavities that smell … of bees.

A cavity that’s already heavily propolised, or contains used drawn comb, offers distinct advantages to the incoming swarm. They will have less work to do and so more chance of building up before winter arrives.

The ideal bait hive

And you can reproduce these requirements by offering a used single brood box National hive with a solid floor and an entrance reducing block in place … facing south and situated well off the ground.

I discussed the evolutionary selection pressures that have shaped the preference for a 40 litre box rather than that convenient spare nuc box I’m repeatedly asked about a smaller box a few weeks ago.

In that post I also discussed why I ignore the preference for bait hives located 5 metres above the ground:

- I want to be able to watch scout bee activity. This is tricky if they’re a long way off the ground {{4}}.

- It’s a lot safer retrieving a bait hive from a hive stand at knee level than it is when climbing a ladder. I usually move occupied bait hives late in the evening (when the bees are all in residence) and prefer not to do this balanced precariously on top of a ladder.

- And – though not listed last time – my knee level bait hives are sufficiently successful I don’t need to increase their attractiveness. I don’t doubt they’d be more efficient located at altitude {{5}} but they work well enough that I don’t feel the need to risk altitude sickness or a broken leg …

But, what I’ve not really discussed before is the location where bait hives should be sited and the importance of appreciating the ‘competitive‘ aspects of bait hives.

Natural competition

When you place a bait hive in the environment, whether it’s in your garden or the corner of a field or 5 metres up an oak tree {{6}}, you are providing a potential nest site that will be judged in competition with other natural sites in the area.

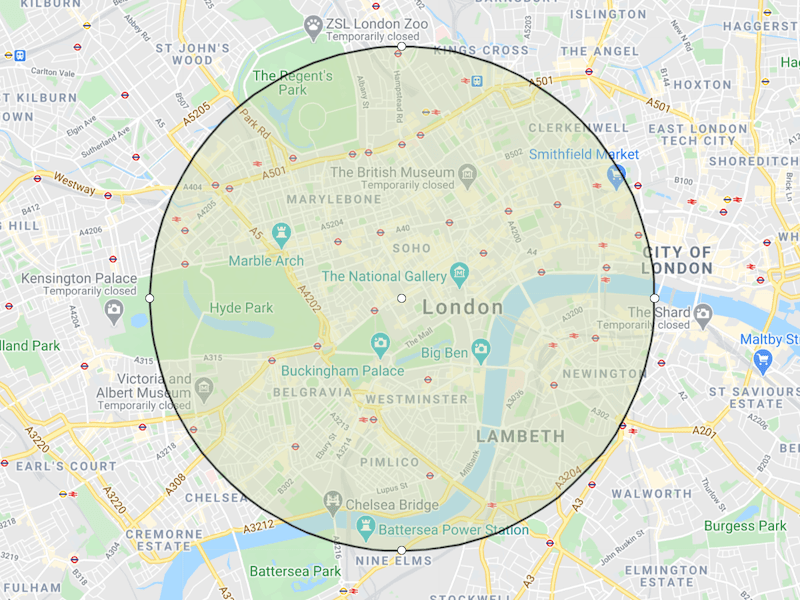

And ‘the area’ is probably about 25 square kilometres.

If you struggle to visualize that then it’s the area covered by this circle centred on the roof of Fortnum & Mason’s, where there are some hives. London Zoo to Battersea Power Station and the Round Pond to Southwark Bridge … a large area {{7}}.

Scout bees survey over 3 km from their nest site, though swarms rarely relocate that far {{8}}.

Why don’t they move ‘that far’?

Again, evolution may have selected bees that choose not to move away from the environment in which the swarming colony has flourished and built up strongly enough to be able to swarm.

Scout bees find nests, they don’t survey the available forage around those nests. So it makes sense to stay in the general area where forage is proven to be good enough (to allow swarming).

However, I suspect a compelling reason that swarms don’t move far from their original nest site is that there are plenty of alternative nest sites available.

Church towers {{9}}, roof spaces, chimneys, tree cavities {{10}}, compost bins, abandoned sheds etc.

Choices, choices

Think about the environment near your hives. Whether urban or rural, there are bound to be thousands of potential cavities within 3 km.

Some will be too small, some will be poorly defendable {{11}} and some will be unsuitable for other reasons.

But there are very likely to be some that are ideal, or pretty close to it.

Mature woodland and older man made environments are likely to have ample choices.

Occupied bait hive …

And then there’s your lonely bait hive.

Chance in a million?

How can it possibly compete with all those natural cavities in the environment?

The first thing to do is to ensure it adheres as close as is practically possible (and safely achievable) to the idealised requirements determined by Martin Lindauer, Thomas Seeley and others.

- a 40 litre cavity = National brood box

- a small entrance of 10-15cm2 = entrance block, solid floor

- south facing

- shaded but in full view

- over 5m above ground level {{12}}

- smelling of bees = one old, dark comb against the sidewall (no stores!)

Secondly, locate it within ~500 metres of your own apiary (to hopefully re-capture your own ‘lost’ swarms {{13}} ) or, more speculatively, anywhere in an environment in which there are other managed or feral colonies.

Which does not mean over the fence from another beekeeper’s apiary!

Be courteous … don’t poach 🙂

The density of bees throughout much of the UK is very high. Look at Beebase to see the numbers of apiaries within 10 km of your own. When I lived in Warwickshire it was ~180-220, in Fife it was ~35-40 {{14}}.

In the talks I’ve given on bait hives this winter – where I customise the presentation to the audience location – few areas with active BKAs have under 100 apiaries within 10 km of their teaching apiary.

In both Fife or Warwickshire I never failed to attract swarms to bait hives in my garden every single year … and in several years up to three swarms to a single bait hive location.

And, with one or two exceptions, these weren’t swarms I had lost {{15}}.

The density of managed colonies in the UK means that a suitable bait hive just about anywhere stands a chance of being occupied.

So, that’s how to win the competition with the natural nest sites that are available.

No competition

But do not put out multiple bait hives in one area.

I have recently re-read an old paper by Thomas Seeley and Kirk Visscher on quorum sensing by scout bees. Quorum sensing is a term for a decision making process where enough bees agree on the same choice, rather than the majority.

Like many good experiments it has an elegant simplicity.

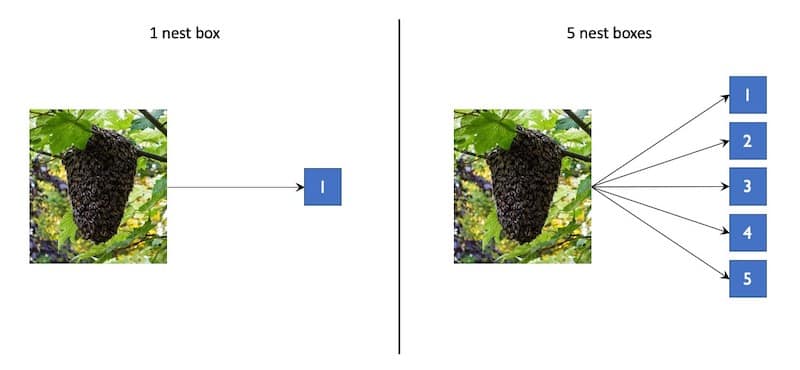

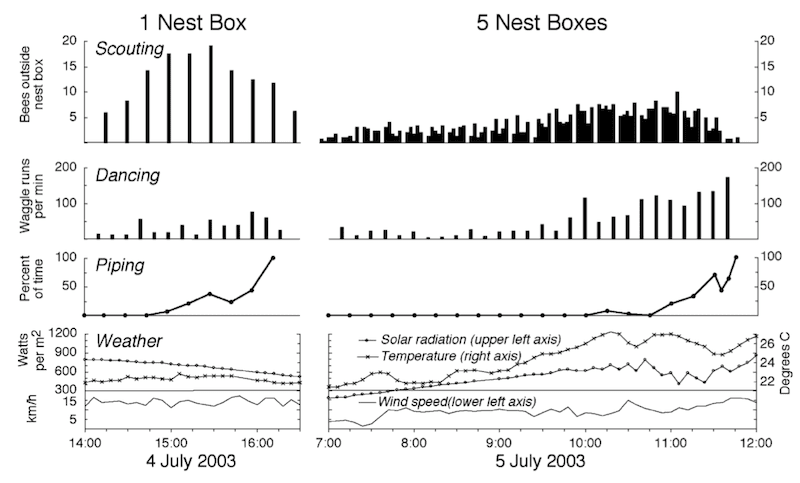

They reasoned that if you provided a bivouacked swarm with a choice of suitable nest sites it would reduce the numbers of scouts that favoured each nest site, and in doing so, would increase the time to reach a decision as to which was best.

And it does.

Unsurprisingly, with more nest box sites to choose between, the scout bees per box were reduced in number (top panel), dancing to advertise preferred nest sites was delayed (second panel), and piping – the ‘prepare for take-off’ signal (third panel) for the bivouacked swarm – was also delayed.

I’ll discuss how this favours a quorum sensing mechanism (and some other aspects of the study) if and when I get time in the future.

For the moment the key take home message is ‘more choice = slower decision making’ by the swarm.

And, if you delay the decision making, there’s a chance it’ll start raining, or the swarm will be collected by another beekeeper … or they’ll opt to move into the old tower of that quaint cartoon church.

One area?

I started the last subsection with the sentence ‘But don’t put out multiple bait hives in one area’.

What is one area?

I was being deliberately vague because I don’t know the answer.

Since I don’t know where the bees might come from {{16}}, I don’t know what’s within range of the bivouacked swarm.

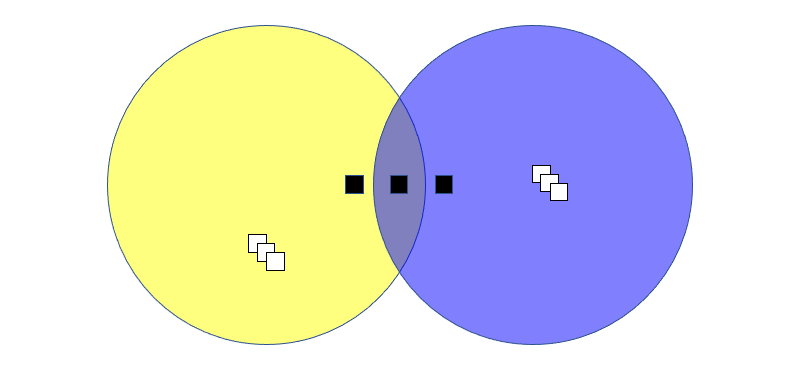

Widely separated bait hives (black) are likely to be within reach of more swarms than clustered bait hives (white)

In practical terms this means I space my bait hives at least 500 metres apart. Widely separated bait hives are likely to be within reach of more swarms than clustered bait hives.

More importantly, clustered bait hives are likely to lead to competition between scout bees from the same swarm, resulting in reduced scout bee attention..

Until recently I’ve not kept bees in my garden. I would always place a bait hive in the garden and one near my out apiaries. With permission, I’d locate them in other places as well.

Having moved, I now have much more space and have bees in the ‘garden’. When my bait hives go out {{17}} they will be placed in likely spots on opposite sides of our bit of scrubby wooded hillside {{18}} .

But what’s a likely spot?

Ley lines

And if you thought that last bit was slightly vague … brace yourself.

Over the years I’ve noticed that some bait hive locations are much more successful than others.

Under offer …

My tiny courtyard garden in Fife was a magnet for swarms. I placed a bait hive in a warm corner of the garden on the day we moved in, and within 10 days a swarm had arrived.

Planting tray roof …

Every year, without fail, multiple swarms would occupy bait hives {{19}} in that corner of the garden. I even had two swarms competing for one bait hive in 2019.

A sheltered south-east facing hedgerow in Warwickshire was equally effective.

Smelling faintly of propolis and unmet promises

As was a south-west facing spot sheltered next to my greenhouse in a previous garden.

Des Res?

But other locations have been far less successful.

Of course, this is a positive reinforcement exercise. I’m more likely to site a bait hive in a location I’ve previously been successful in.

But what else might account for this differential success rate? And can it be exploited in the rational location of bait hives?

Is it, as some suggest, that bait hives work best when they are located at the intersection of ley lines? This, and the possibility of creating Varroa-resistant bees by exploiting geopathic stress lines, surely deserves a post of its own {{20}}.

Call me sceptical

However, as a scientist – and knowing others have been more than a little sceptical about the existence of ley lines – I think there’s a more prosaic explanation.

Without exception, my most successful sites for bait hives have been well sheltered to the north, and – in most cases – to the north-east and north-west directions as well.

For example, the bait hive is situated on the south face of a wall running east-west (Under offer, above), or in a corner sheltered to the north and east (Planting tray roof, above), or facing south-east in a very dense hedgerow running north-east to south-west (Smelling faintly etc., above), or sheltered by surrounding walls or outhouses but with a clear entrance facing south-west (Des res?, above).

And … since I’ve been aware of this for at least five years, and probably subconsciously aware of it for much longer, that’s exactly the type of location I choose to site my bait hives.

Which is, of course, another example of positive reinforcement 🙂

However, it works for me. I choose sites that are well sheltered to the sides and back of the bait hive, and I try and orientate the bait hive to face south (ish).

At knee level 😉

Give it a try.

{{1}}: Hence the alternative name, swarm trap.

{{2}}: And why you should not use open mesh floors on bait hives.

{{3}}: Or, presumably an early hominid hunter-gatherer … or a honey badger (which, I’ve just learned from Google, can also climb trees).

{{4}}: So emphasising the selective pressure from bears, honey badgers and early hominids that have forced them to choose nest sites at altitude in the first place.

{{5}}: Evolution is rarely wrong.

{{6}}: Don’t, just don’t!

{{7}}: And a useless comparison for those unfamiliar with London … sorry.

{{8}}: I’ve discussed how far swarms disperse previously and it’s usually less than half a kilometre.

{{9}}: Whether quaint or not.

{{10}}: The enthusiasm with which old trees are felled – for ‘safety’ or to route a new railway – means that, ironically, tree cavities may be in short supply.

{{11}}: Notwithstanding the absence of bears, honey badgers or early hominids.

{{12}}: Don’t say I didn’t warn you …

{{13}}: Again, surely not?

{{14}}: Here on the remote west coast it’s just 1 … and that’s mine.

{{15}}: As if!

{{16}}: Insert standard quip here about not being from one of my hives …

{{17}}: It’s still far too early here …

{{18}}: With almost zero expectation of attracting a swarm as my queens are clipped, my swarm control is awesome and there are no other beekeepers within 5 miles. CAUTION. One of those three statements is not entirely accurate.

{{19}}: Of all sorts of different types, so it wasn’t the hive per se, or even its orientation as I sometimes had them facing west instead of south.

{{20}}: Don’t hold your breath.

Join the discussion ...