More queen rearing musings

I described queen rearing last week as The most fun you can have in a beesuit ™. That’s my opinion. You may prefer making candles, or beeswax wraps or extracting and jarring honey {{1}} and I wouldn’t argue, though none of them come close to the satisfaction I get from queen rearing.

The term ‘queen rearing’ sometime conjures up images of booming, chest-high queenless cell starters, dozens of grafted larvae on each cell bar frame, incubators and serried rows of mini-nucs waiting for virgins … or even clinical instrumental insemination apparatus.

Capped queen cells on a cell bar frame (produced using the Ben Harden queenright queen rearing approach)

This is the industrial scale production of queens, and it’s rare that enthusiastic but nevertheless small-scale amateur beekeepers need that number of queens.

Or have the resources to produce them.

For convenience I think of queen rearing as an activity that can occur at three different scales:

- One or two queens at a time – e.g. adding a frame of selected (i.e. good quality) eggs/larvae to a terminally queenless hive. Surplus cells can be cut out and distributed elsewhere.

- Five to ten at a time – often using selected larvae transferred to a cell starter colony by grafting, a Cupkit-type system, cell punching or (fewer manipulations still) the Miller or Hopkins methods.

- Dozens of queens at a time – almost always using grafting and a strong queenless cell starter colony.

I’ve run 10-20 colonies for a decade or more and rarely need more than 20 queens a season (a number which includes some spares to make up nucs).

In addition, I live in an area with variable (i.e. often poor) weather where queen mating can be ’hit and miss’.

Little and often

For these reasons I prefer to produce a few queens at a time so I don’t have to devote significant resources to an activity that might be thwarted by a month of lousy weather.

I’d rather try and produce half a dozen queens three or four times a season, than dozens at once.

The latter requires a major commitment of resources (colonies and equipment). Depending upon the weather I might end up with a glut of queens.

Or an apiary-full of laying workers 🙁

In contrast, the methods I use allow me to produce a handful of queens every few weeks. If the weather is kind, all will get mated. If not, it’s not a total disaster.

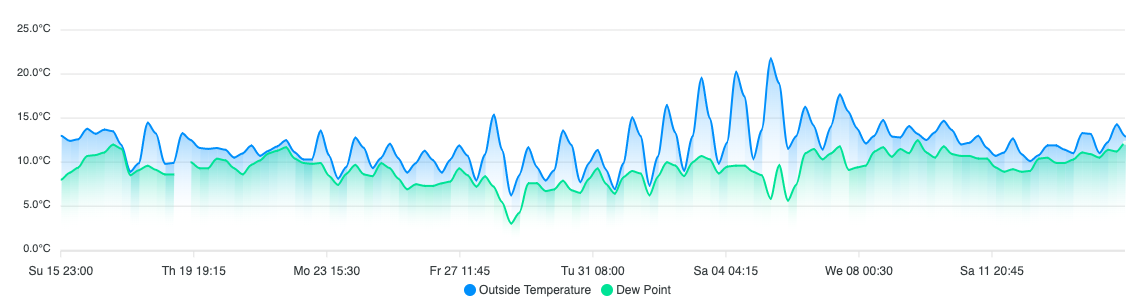

Over the last month we’ve only had 2-3 days with conditions normally associated with successful queen mating i.e. light winds, sunshine and temperatures of 20°C.

Predicting this type of ‘weather window’ 2-3 weeks in advance is almost impossible.

It’s better to be prepared to repeat things again.

And again 😉

Apiary vicinity mating

In fact, queens don’t need ‘perfect’ conditions for mating. If they did, sustainable beekeeping {{2}} would be impossible – or at least very difficult – in many northern latitudes. Queens can be successfully mated in sub-optimal conditions {{3}}.

Part of my interest in monitoring the local weather at my apiary is to try and determine just how poor the conditions can be whilst still getting queens mated.

Native Apis mellifera mellifera (black bees) are reported to use apiary vicinity mating (AVM) and so may not need optimal conditions to fly to distant drone congregation areas. Jon Getty has written more about AVM on his website.

However, wherever or whenever they get mated, I prefer to produce repeated batches of queens using queenright cell raisers. By doing this I’m not putting all my ‘eggs in one basket’. Essentially these cell raisers are standard (honey) production hives manipulated in simple ways to provide the conditions needed to rear suitably-presented larvae as queens.

And inevitably, because they’re queenright, things can sometimes go wrong 🙁

Queenright queen rearing

The two methods I’ve used are the Ben Harden approach and a Morris board. Both use a single colony to start and finish the queen cells, and the queen remains present – albeit separated from the developing cells – throughout the 10-12 days from grafting until the cells are used.

The Morris board

A Morris board is essentially the same as a Cloake board. These are boards that separate the queenright lower brood box from an upper brood box in which the queen cells are produced. The board has an integrated queen excluder and the provision to separate the upper and lower box with a metal or plastic divider.

With the divider inserted queen cells are started in the top box under the emergency response. However, once started, the divider is removed and the cells are finished under the supersedure response.

The Morris board is more complicated than a Cloake board; it is used with a divided upper brood box – allowing separate batches of cells to be started every week or so – and has a series of doors for bleeding off and redirecting returning foragers to the correct compartment.

It’s a clever idea and one that shows considerable promise for my queen rearing.

I’ll write more about my use of a Morris board in due course, or you could track down the article Michael Badger wrote in Bee Craft.

The Ben Harden approach

I’ve discussed the Ben harden approach extensively already – try here for starters. The method, although perhaps popularised by the eponymous Irish beekeeper (and excellent instructors like the late Terry Clare) was also described nicely by the National Bee Unit’s Mike Brown and David Wilkinson twenty years ago in the American Bee Journal {{4}}.

Preliminary setup for Ben Harden queen rearing (note the ‘fat dummies’ occupying much of the upper box)

Until the last couple of years this is the method I’ve used for most of my queen rearing.

The queen is confined below a queen excluder to the lower brood box. Grafted larvae are added to the upper box, space within which is often restricted by the use of ‘fat dummies’.

The queen cells are therefore started and finished under the supersedure response.

Supersedure vs. swarming responses and colony swarming

In preparation for swarming a colony naturally produces several charged queen cells {{5}}. Assuming the weather is suitable, the colony usually swarms on the day that the first cells are sealed.

If the weather is poor then swarming is delayed, but they often then go at the first opportunity … so much so that even a borderline day after a period of poor weather during the normal swarming season is often characterised by lots of swarms.

In contrast, newly sealed supersedure cells – and these are usually very few in number (often just one) – are incubated for a further 8 days until emergence of the virgin queen.

The superseding colony does not swarm.

The new queen goes on a few mating flights and starts laying.

At some point after that the old queen simply disappears.

One day you’re surprised to find two laying queens in the hive but at the next inspection (or the one after that) only the shiny new one remains.

The queen is dead, long live the queen.

Advantages (and disadvantages) of queenright queen rearing methods

For the small scale beekeeper – perhaps 2-20 colonies – queenright methods offer a number of advantages (with a few disadvantages) for queen rearing:

- the quality of the cell starter/finisher is immaterial as long as the colony is strong. You simply provide it with larvae from good quality stock.

- no interruption {{6}} to nectar collection. In a good nectar flow you simply keep piling on supers as needed and the bees raise the cells and fill the supers.

- if there’s no nectar flow you will have to feed the colony, so you must remove any supers to avoid tainting any stored nectar with syrup.

- if you do simultaneously use the colony for honey production and cell raising the hive can get tall and heavy. Mind your back.

- you can use a single hive for the entire process if needed; cell starter, sourcing larvae, cell finisher and populating mini-nucs. You might even get some honey as well 😉 {{7}}

The queenright methods outlined above exploit the supersedure response for cell raising. This means that the colony will not swarm in response to capping of the cells in the upper box.

But …

That is not the same as saying that the colony will not swarm 🙁

Don’t forget, there’s a laying queen in the bottom box. She will continue to lay while the new cells are being started, fed, nurtured and sealed.

And if she runs out of space the colony can still make swarm cells in the bottom box and so may swarm.

Here are a couple of examples where this has happened … and the consequences for my queen rearing.

A swarming Ben Harden cell raiser

When I lived in the Midlands I routinely started queen rearing during April. Queens produced in April could be mated as early as the first week of May in a good year, and occasionally, even earlier.

Colonies got a massive boost during this part of the season from the oil seed rape. The photo below is from the 19th of April 2014.

When rearing queens using the Ben Harden approach during a strong nectar flow you can safely relocate the upper brood box above the top super. In a busy hive the developing cells still get more than enough attention.

In addition, this can help increase ‘take’ {{8}} by reducing the concentration of queen pheromones due to the separation of the bottom brood box (containing the original queen) and the box containing the grafted larvae.

When using this method it is important to check the upper box for queen cells on the day the grafts are added. This box, being separated from the queen-containing brood box, has reduced queen mandibular, and no queen footprint, pheromones.

Consequently, it’s not unusual for the bees to start drawing queen cells. These must be destroyed or – being more advanced than the grafted larvae – they will emerge first and destroy all your hard work.

I had done this and added the grafts which, on checking 24 hours later, had all been accepted.

Chipmunks are Go! {{9}}

Out of sight is out of mind

However, I had failed to check the bottom box for queen cells on the days before I added the grafted larvae.

The colony promptly swarmed, probably before the newly developing queen cells were capped.

This was either before I routinely clipped my queens, or I’d missed this particular queen. Whatever, she and a significant proportion of the bees disappeared to pastures new.

I can’t remember how (or when) I realised the colony had swarmed. It might have been reduced entrance activity during the strong OSR nectar flow, or I might have just (finally!) conducted a regular inspection.

The bottom box contained sealed queen cells, no queen and no eggs 🙁

But, all was not lost.

The cells containing grafted larvae were capped and looked good. They’d clearly received sufficient attention {{10}} and I was therefore hopeful they’d emerge, mate and produce usable queens.

And they did.

I knocked back all the sealed queen cells in the bottom box and then – on the day I used the cells from the grafted larvae – added one of the latter to the lower brood box.

I removed the queen cells in the lower box for two reasons:

- it prevented a new queen emerging there while I had cells above the queen excluder, and

- it allowed me to use a cell raised from larvae sourced from a better quality colony.

So, a swarming cell raiser isn’t necessarily a disaster.

A more recent, but less successful, attempt

My first attempt at queen rearing this season involved using a Morris board.

I added the Morris board and upper brood box on the 18th of May. I then did all of the necessary Morris board manipulations – closing the slide, opening entrances, closing others – to pack the upper box with bees.

On the 25th I did the grafting and – at the same time I added the grafts on the cell bar frame – I destroyed a small number of queen cells in the upper box {{11}}.

On the following day 7-8 of the larvae had been accepted and the cells were capped on or around the 30th.

I was off beekeeping elsewhere so didn’t check the hive again until the 1st of June … and was dismayed to find all of the cells had been torn down.

There was no queen in the upper box and the queen excluder was intact. The cells appear to have been torn down by workers. I’ve had this happen before when there’s been a dearth of nectar, but this box was getting 300 ml of thin syrup every 48 hours.

D’oh!

Of course, I eventually checked the bottom box and found:

- one vacated queen cell. This cell was situated on the lower edge of one of the central frames.

- a virgin queen running about and no sign of the original clipped and marked queen 🙁

The single queen cell might suggest supersedure. However, its position (though far from a reliable indicator) was more like that of a swarm cell.

In addition, the absence of eggs or any sign of the original queen, strongly suggested that the colony had swarmed. This probably happened – coincidentally – on the day the cells containing the grafts were sealed.

I say ‘coincidentally’ because I suspect the swarming was triggered by emergence of the new queen in the lower box and had nothing to do with my grafted larvae. That would fit with two things – the timing of the previous inspection (18th) and the fact that swarming is delayed when the incumbent queen is clipped.

However, because she was clipped, the colony was not depleted of workers. The original queen was lost, but that was all.

An alternative interpretation would be that the new queen simply did away with the original queen.

But why were the cells containing grafted larvae torn down?

One possibility was that the new queen pheromones were sufficiently strong that the workers realised they didn’t need additional queens. Alternatively – though she wasn’t by the time I saw her – I suppose there’s a possibility that the virgin queen was small enough to squeeze through the queen excluder, slaughter the developing queens, and squeeze back down to the lower box.

Learning from my mistakes {{12}}

Both examples above were due to my not maintaining a proper inspection schedule on the lower, queenright, brood box.

Guilty, m’lud.

Despite the advantages outlined above, cell rearing colonies should still be treated in the same way – vis-à-vis regular inspections – as any other production hive.

Other than forgetfulness, sloth and stupidity {{13}} there’s no reason not to inspect the lower brood box properly on a 7 day cycle.

Once the larvae are accepted you can remove the upper box (and all the bees it contains), gently set it aside and go though the bottom box. The workers with the developing queen cells will look after them for the 10 minutes or so this takes.

Conversely, there’s no reason to interfere with the upper box other than to check acceptance and confirm, in due course, that the cells are sealed. If you assemble the queenright cell rearing colony and wait a week before adding grafts to the upper box (as described above) they cannot start new queens from anything other than the larvae you add.

What else would you be looking for?

Just one more thing {{14}}

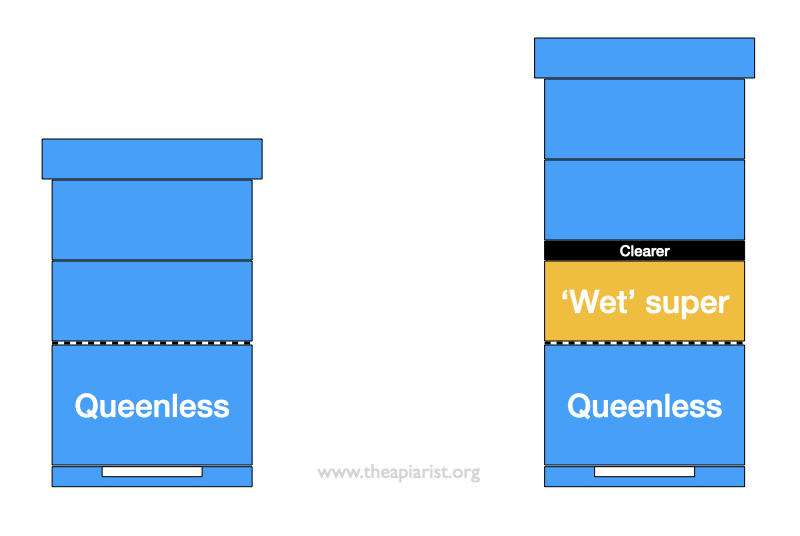

There were several comments last week about honey production in queenless colonies.

I collected more supers on Monday containing spring honey. This included recovering supers from several queenless (or currently requeening – some may have contained virgins) colonies.

I have previously noticed that supers are cleared less well – using my standard clearer boards overnight – from queenless colonies.

You always get a few bees remaining in the super, but there were consistently lots more in queenless colonies.

I didn’t count them … few is less than some, which is quite a bit less than lots, which – in turn – is appreciably less than ‘did I put the clearer on inverted?’

This was the second batch of supers I’d collected, a week after the first. I’d left the supers on longer because:

- there were too many to transport

- some still had unripe nectar which failed the ‘shake test’ over a hive roof (see photo below), indicating that the water content was too high to extract without risking the honey fermenting

Luring the bees down from the supers

In an attempt to speed up clearing bees from the supers of queenless colonies I added the clearer underneath the full supers, but on top of a wet super from which I’d already extracted honey.

This worked well.

The heady smell of honey {{15}} in the wet super resulted in significantly fewer bees in the cleared supers.

I have to transport these cleared supers ~200 miles back home for extraction. If I had a trailer or a truck a few stragglers wouldn’t normally be an issue.

But I don’t … these supers are in the car with me.

Biosecurity

Actually … stragglers would still be an issue, even with a trailer/truck.

My Fife bees have Varroa (low levels, but it’s definitely present) but my west coast bees do not. I take biosecurity seriously and don’t like finding any bees in the car after the journey.

I also really don’t like finding bees in the car at 65 mph on the A9 … and, if I do, I stop and let them out.

The combination of the better-cleared supers and a sharp thwack on any frames with adhering bees reduced the stowaways to zero.

And the five hour return journey {{16}} was notable for stellar views of an osprey, a stunning male hen harrier and the sun setting over Creag Meagaidh 🙂

{{1}}: Undoubtedly The worst part of successful beekeeping ™ … again, my opinion, but I’m not wrong am I?

{{2}}: i.e. not dependent upon imports or buying-in queens or nucs.

{{3}}: Though perhaps not the rain we’ve had this week!

{{4}}: Wilkinson and Brown (2002) Rearing queen honey bees in a queenright colony ABJ April 2002 pp270 (available as a PDF)

{{5}}: i.e. containing well-fed larvae.

{{6}}: Or minimal interruption.

{{7}}: I’ve done this. It works but it’s not ideal; you have no option to use ‘better’ larvae and the colony usually ends up being split up before the main summer nectar flow.

{{8}}: The number of grafted larvae accepted by the colony and reared as queens.

{{9}}: Yikes! … no idea how or why that popped into my mind. Maybe it’s the caffeine? Chipmunks are Go! was the last track on the Madness’s 1979 debut album One step beyond. However, I’m sure I remember the phrase – meaning ’All good … onward and upward’ from earlier in my childhood. A kids cartoon perhaps?

{{10}}: I like the exterior of the cell to be heavily sculpted by attending workers. See the first image this week for an example.

{{11}}: These would have been started, as described above, due to reduced queen pheromone concentrations. After one week there are no larvae young enough to be used for queen production – other than those you add – so you only need to perform this check once.

{{12}}: That’s likely to be my epitaph … followed by the word ‘slowly’.

{{13}}: All of which probably apply to the examples above.

{{14}}: As Columbo would say.

{{15}}: At least, that’s what I assume encouraged them down.

{{16}}: Camper vans, the bane of my life at this time of the year.

Join the discussion ...