More local bee goodness?

Before the wind-down to the end of the year and the inevitable review of the season I thought I’d write a final post apparently supporting the benefits of local bees. This is based on a recently published paper from the USA {{1}} that tests whether local bees perform better than non-local stocks.

However, in my view the study is incomplete and – whilst broadly supportive – needs further work before it can really be seen as an example of better performing local bees. I suspect there’s actually a different explanation for their results … that also demonstrates the benefits of local bees.

This is a follow-up to a post three weeks ago that provided evidence that:

- Colonies derived from different geographic regions show physiological adaptations (presumably reflecting underlying genetic differences) that seem pretty logical e.g. bees from Saskatchewan express more proteins involved in heat production, whereas Hawaiian bees show higher levels of protein turnover (which would make sense if they had evolved locally to have high metabolic rates).

- In a study by Büchler, European colonies survived better overwinter in their local environment; a fact subsequently attributed to the colonies being stronger going into the winter. In turn, this agrees with a recent study that clearly demonstrates the correlation between overwintering success and colony strength.

I suggest re-reading {{2}} that post as I’m going to try and avoid too much repetition here.

Strong colonies

Strong colonies overwinter better and – if you’re interested in that sort of thing – are much more likely to generate a profit for your honey sales.

So how can you ensure strong colonies at the end of the season?

What influences colony strength?

One thing is colony health. A healthy colony is much more likely to be a strong colony.

In the ambitious 600-colony Büchler study in Europe they didn’t do any disease management. The colonies were monitored over ~2.5 years during which time 84% of colonies perished, at least half due to the ravages of Varroa.

Clearly this is not sustainable beekeeping and doesn’t properly reflect standard beekeeping practices.

Study details

The recent Burnham study makes a nice comparison to the Büchler study.

It was conducted in New York State using 40 balanced {{3}} colonies requeened in late May.

Queens were sourced from California (~4000 km west) or Vermont (~200km east in the neighbouring state, and therefore considered ‘local’) and colonies were assigned queens randomly.

Unlike some previous studies the authors did not evidence the genetic differences between queens.

However, the queens looked dissimilar and the stocks were sourced from colonies established in California or Vermont for at least 10-15 generations. I think we can be reasonably confident that the queens were sufficiently distinct to be relevant for the tests being conducted.

Colonies were maintained using standard beekeeping practices, Varroa levels were managed using formic acid (MAQS for European readers) and the colony weight and productivity (frames of bees) was quantified, as was the pathogen load.

In contrast to the Büchler study, Burnham and colleagues only followed colonies over one beekeeping summer season. This was not a test of overwintering survival, but mid-season development.

Results

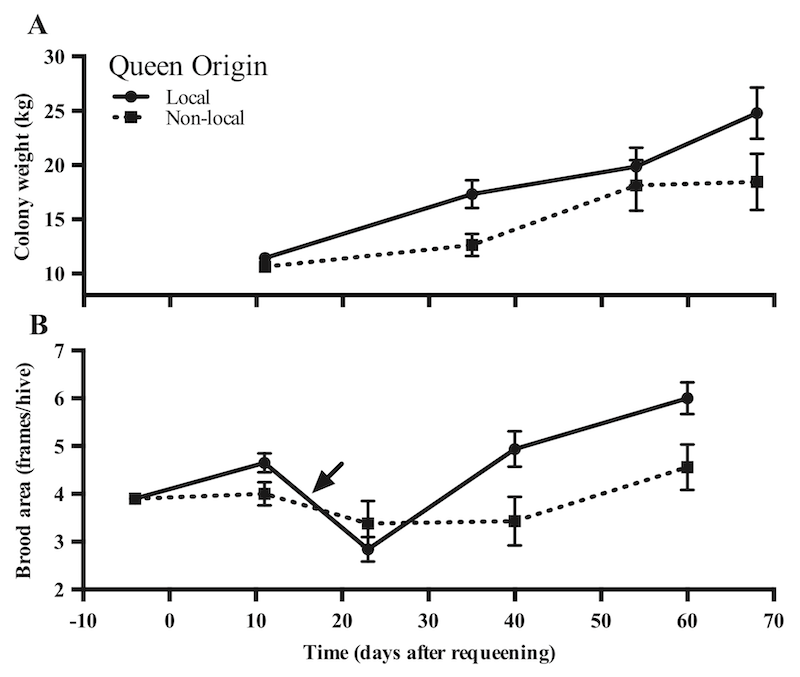

The take-home message is that colonies headed by the ‘local’ Vermont queens did better. The colonies got heavier faster and brood levels built up better.

It’s notable that colony weight built up before any brood would have emerged from the new queen (upper panel) and that brood level in colonies headed by the local queen recovered much better after formic acid treatment (arrow in lower panel).

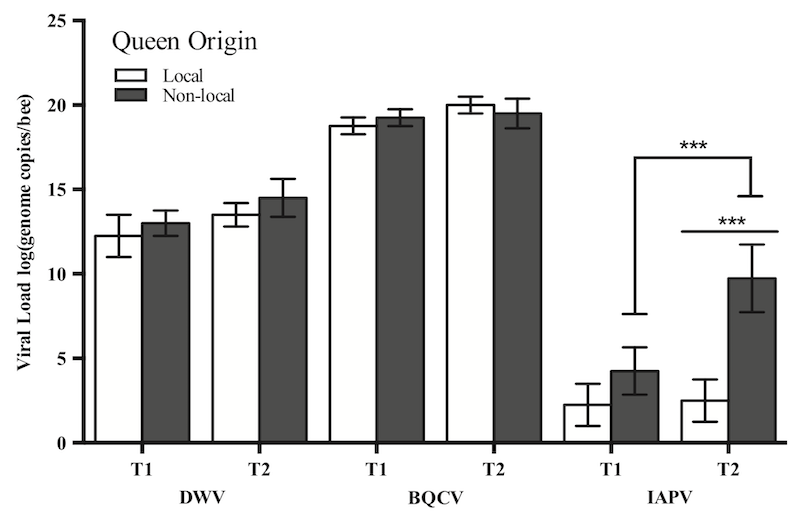

However, Nosema levels were significantly different (above) as were the levels of Israeli Acute Paralysis Virus (IAPV; below).

There were no significant differences in the Varroa loads before or after treatment (not shown), or in the levels of DWV or Black Queen Cell Virus (BQCV).

Taken together – bigger, heavier, stronger colonies and lower pathogen loads (at least of some pathogens) – seems good evidence to support the contention that local bees are beneficial.

The benefits are precisely what you want for good overwintering – strong, healthy colonies.

That’s a slam-dunk then?

Case proven?

No.

IAPV is a virus rarely detected in the UK. It causes persistent and systemic infections in honey bees and can be found in every caste (drones, workers, queens) and at every stage of the life cycle.

As IAPV is detectable in eggs and larvae – neither of which are Varroa-exposed – it is assumed to be vertically transmitted from the queen. IAPV is also found in the ovaries of the queen, which is additional evidence for vertical transmission.

At the first timepoint (12 days post requeening) the levels of IAPV are different between the two colony types, but not significantly so. However, by 40 days (T2) the levels are very different. At this later timepoint all the bees in the colony will be have come from the introduced queen.

The authors explain the differences in IAPV levels in terms of local bees being more resistant to ‘local’ pathogens … in much the same way that Pizarro’s 168 conquistadors, being more resistant to smallpox, defeated the might of the Inca Empire with the help of the virus diseases they inadvertently introduced to Peru.

I suspect there’s another explanation.

Perhaps the Californian queens were IAPV infected from the outset?

If this was the case they could introduce a new and virulent strain of IAPV to the research colonies and – over time – the levels would increase as more and more workers in the colony were derived from the new queen. IAPV is present in ~20% of US colonies so it seems perfectly reasonable to suggest it might have been largely absent from the Vermont queens and the test colonies, but present in the queens introduced from California.

How should they have tested that?

The obvious thing to do would be to characterise the IAPV present in the colony. IAPV shows geographic variation across the USA. If the predominant virus was of Californian origin it would suggest it was brought in with the queen. This is a relatively easy test to conduct … a sort of 23andme to determine bee virus provenance.

Alternatively, though less conclusively, you could do the experiment the other way round … ship Vermont queens to California and compare their performance with colonies headed by Californian queens on their own territory. If the Californian queens again performed less well it undermines the ‘local bees do better’ argument and suggests another explanation should be sought.

Nosema is sexually transmitted but it is not vertically transmitted, so the same arguments cannot be made there. Why the Nosema levels drop so convincingly in colonies headed by the local queens is unclear. Nosema was present at the start of the study and was lost over time in the stronger colonies headed by the local queens.

One possibility of course is that the stronger colonies were better fed – more workers, more foragers, more pollen, more nectar. Improved diet leads to a more active and effective immune system and an increased ability to combat pathogens. Simplistic certainly, but it is known that diet influences pathogen resistance and colony performance.

So what does this paper show?

I suspect it doesn’t directly show what the authors claim (in the title) … that local queens head colonies with lower pathogen levels.

This largely reflects the lack of proper or complete controls. However, it does not mean that local bees are not better.

More than anything I think this paper demonstrates the impact queen quality has on colony performance.

Perhaps the Vermont-sourced queens were just better queens. Local certainly (on a USA scale definition of the word local), but not better because they were local, just better because they were better.

However, if my interpretation of the source of the IAPV is correct i.e. introduced from the Californian queens, I think the paper indirectly demonstrates one of the most compelling reasons why local bees are preferable.

If they’re local – your apiary, your neighbours, someone in your association – there is little chance they will be bringing with them some unwanted baggage in the form of an undetected exotic pathogen.

Or a more virulent strain of one already circulating relatively benignly.

Extensive bee movements, whether of queens, packages or full colonies, risks spreading parasites and pathogens.

There is compelling evidence that hosts and pathogens co-evolve to reduce the pathogenicity of the interaction. Naive hosts are always more susceptible to introduced pathogens, or novel strains of pre-existing pathogens. After all, look what happened to the Peruvian Inca when they met the measles- and smallpox-ridden conquistadors.

So, when thinking about the claims being made by bee importers (or, for that matter, strong advocates of local bee breeding), it’s worth considering all of the factors at play – queen quality per se, genetic adaptation of the queen to the local environment and the potential for the introduction of novel pathogens with introduced non-local stock.

And that’s before you also consider the benefits to your beekeeping of being self-sufficient and not reliant on others to produce your stocks.

I never said it was simple 😉

{{1}}: Burnham et al., (2019) Local honey bees (Apis mellifera) have lower pathogen loads and higher productivity compared to non-local transplanted bees in North America. Journal of Apicultural Research 58:694-701.

{{2}}: Or reading for the first time – in which case, welcome ;-)

{{3}}: i.e. the numbers of brood frames and bees were equalised across all colonies.

Join the discussion ...