More from the fun guy

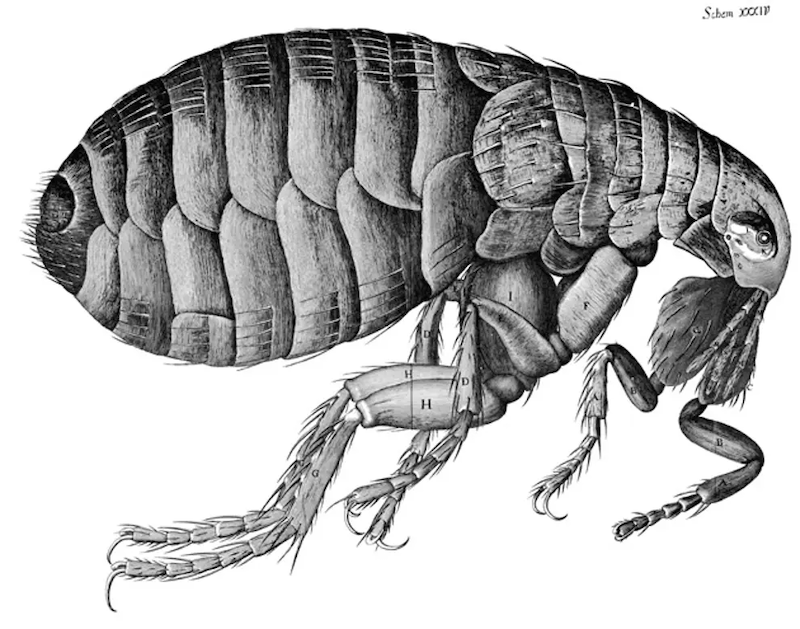

Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite ’em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum.

Augustus de Morgan’s quote from A Budget of Paradoxes (1872) {{1}} really means that everything is preyed upon by something, which in turn has something preying on it.

As a virologist I’m well aware of this.

There are viruses that parasitise every living thing.

Whales have viruses and so do unicellular diatoms. All the ~30,000 named bacteria have viruses. It’s likely that the remaining 95% of bacteria that are unnamed also have viruses.

There are even viruses that parasitise viruses. The huge Mimivirus that infects amoebae {{2}} is itself parasitised by a small virophage (a fancy name for a virus that infects viruses) termed Sputnik.

Whether these interactions are detrimental depends upon your perspective.

The host may suffer deleterious effects while the parasite flourishes.

It’s good for the latter, but not the former.

Whether these interactions are detrimental for humans {{3}} also depends upon your perspective.

The deliberate introduction of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus to Australia benefitted sheep farmers who were plagued with rabbits … but it was bad news for rabbit farmers {{4}}.

Biocontrol

Beneficial parasitism, particularly when humans use a pathogen to control an unwanted pest, is often termed biocontrol, a convenient abbreviation for biological pest control.

There are numerous examples; one of the first and best known is control of greenhouse whitefly infestations with the parasitoid wasp Encarsia formosa.

One of the benefits of biocontrol is its self-limiting nature. The wasp will stop replicating once it runs out of whitefly to parasitise.

A second benefit is the specificity of the interaction between the host and whatever is administered to control it; by careful selection of the biocontrol agent you can target what you want to eradicate without lots of collateral damage.

Finally, unlike toxic chemicals such as DDT, the parasitoid wasp – and, more generally, other biocontrol agents – do not accumulate in the environment and cause problems for the future.

And, with all those benefits, it’s unsurprising to discover that scientists have investigated biocontrol strategies to reduce Varroa mite infestation of honey bee colonies.

It’s too early for an aside, but I’ll make one anyway … I’ve discussed the potential antiviral activity of certain fungi a couple of years ago. That wasn’t really biocontrol. It was a fungal extract that appeared to show some activity against the virus. Although that story has gone a bit quiet, one of the authors – Paul Stamets – is also a co-author of the Varroa control paper discussed below.

Biocontrol of Varroa using entomopathogenic fungi

Entomopathogenic means insect killing {{5}}. There are several studies on the use of insect killing fungi to control Varroa {{6}}, with the most promising results obtained with a variety of species belonging to the genus Metarhizium.

Metarhizium produces asexual spores termed mitospores. The miticidal activity is due to the adhesion of these mitospores to Varroa, germination of the spore and penetration by fungal hyphae {{7}} through the exoskeleton of the mite and proliferation within the internal tissues.

A gruesome end no doubt.

And thoroughly deserved 🙂

Although Metarhizium is entomopathogenic it has a much greater impact on Varroa than it does on honey bees. This is the specificity issue discussed earlier.

It is for this reason that scientists have continued to explore ways in which Metarhizium could be used for biocontrol of Varroa.

But there’s a problem …

Although dozens of strains of Metarhizium have been screened, the viability – and therefore activity – of the mitospores is significantly reduced by the relatively high temperatures within the colony.

The spores would be administered, they’d show some activity and some Varroa would be slaughtered. However, over time treatment efficacy would reduce as spores – either administered at the start of the study, or resulting from subsequent replication and sporulation of Metarhizium on Varroa – were inactivated.

As beekeepers you’ll be familiar with the limitation this would impose on effective control of mites.

Varroa spend well over half of their life cycle capped in a cell while it feeds on developing pupae. Anything added to kill mites must be present for extended periods to ensure emerging mites are also exposed and killed.

This is why Apiguard involves two sequential treatments of a fortnight each, or why Apivar strips must be left in a hive for more than 6 weeks.

In an attempt to overcome these limitations, scientists are using directed evolution and repetitive selection to derive strains of Metarhizium that are better able to survive within the hive, and so better able to control Varroa than the strains they were derived from.

Good news and bad news

Like many scientific papers on honey bees {{8}} those with even a whiff of ‘saving the bees’ get a lot of positive press coverage.

This often implies that the Varroa ‘problem’ is now almost solved, that whatever tiny, incremental advance is described in the paper represents a new paradigm in bee health.

This is both understandable and disappointing in equal measure.

It’s understandable because people (not just beekeepers) like bees. News publishers want ‘good news’ stories to intersperse with the usual never-ending menu of woe they serve up.

It’s disappointing because it’s a variant of “crying wolf”. We want the good news story to describe how the impact of Varroa can now be easily mitigated.

It gets our hopes up.

Unfortunately, reality suggests most of these ‘magic bullets’ are a decade away from any sort of commercial product.

They will probably get mired in licensing problems.

And they may not be any better than what we currently use.

You finally end up as cynical as I am. This might even force you to read the original manuscript, rather than the Gung ho press release or the same thing regurgitated on a news website.

And, if you do that, you’ll better understand some of the clever approaches that scientists are applying to the development of effective biocontrol for Varroa.

We’re not there yet, but progress is being made.

V e r y s l o w l y.

The paper I’m going to discuss below is Han, J.O., et al. (2021) Directed evolution of Metarhizium fungus improves its biocontrol efficacy against Varroa mites in honey bee colonies. Sci Rep 11, 10582.

It’s freely available should you want to read the bits I get wrong 😉

Solving the temperature-sensitivity problem of mitospores

The strain of Metarhizium chosen for these studies was M. brunneum F52. This had previously been demonstrated to have some efficacy against Varroa. Almost as important, it can be genetically manipulated and there was some preliminary evidence that its pathogenicity for Varroa – and hence control potential – could be improved.

Genetic manipulation covers a multitude of sins. It could mean anything from selection of pre-existing variants from a population to engineered introduction of a toxin gene for destruction of the parasitised host.

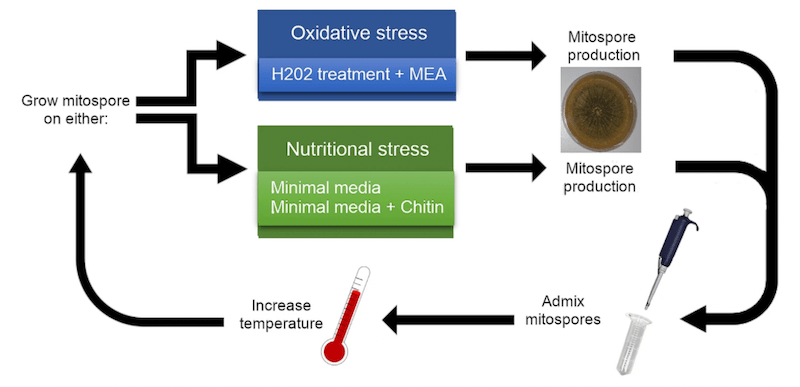

In this study the authors used directed evolution of a population of Metarhizium to select for strains with more heat tolerant spores.

This is not genetic engineering. They grew spores under stressful conditions and increasing temperatures. Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) , a mild mutagen, was added in some cases. Nutritional stress also increases population variation. Spores selected using nutritional stress are better able to withstand UV and heat stress.

The optimal growth temperature for the strain of Metarhizium they started with was 27°C. By repeated selection cycles at increasing temperatures they derived spores that grew at 35°C, the temperature within a colony.

Ladders and snakes

A well known phenomena of repeated selection in vitro (i.e. in a test tube in the laboratory, though you actually grow Metarhizium on agar plates) is that a pathogen becomes less pathogenic.

It was therefore unsurprising that – when they eventually tested the thermotolerant spores – only about 3% of the Varroa that died did so due to Metarhizium infection.

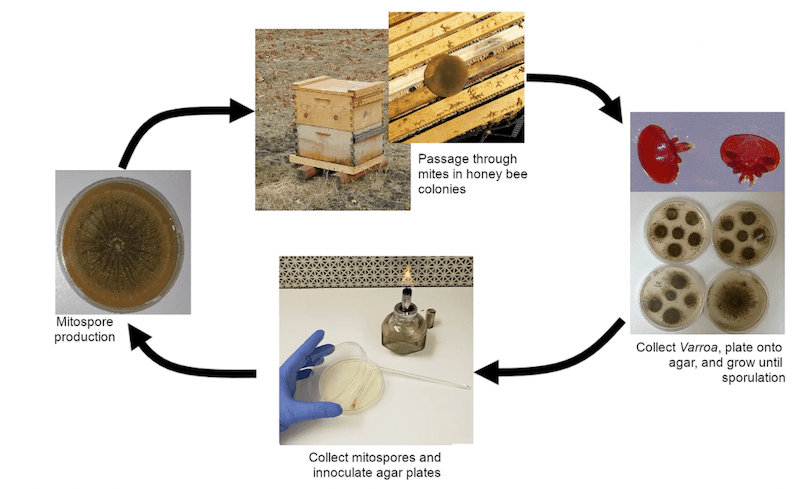

They therefore modified the repetitive selection, but this time did it on Varroa-infested colonies in the apiary. Mites that died from Metarhizium mycoses {{9}} were used as a source to cultivate more Metarhizium.

They were therefore selecting for both thermotolerant (because the experiments were being conducted in hives at 35°C) and pathogenic fungi, because they only cultivated mitospores from Varroa that had died from mycoses.

And it worked …

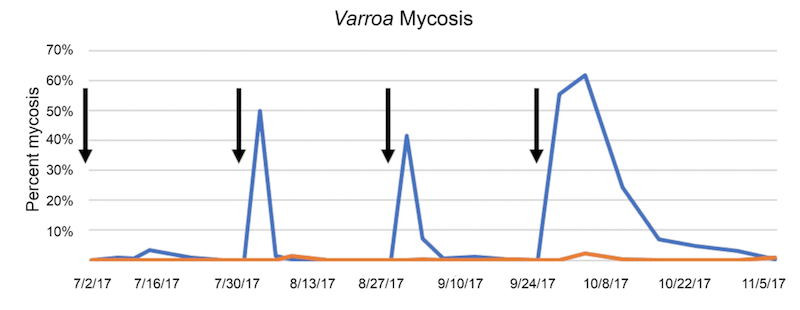

After four rounds of selection over 60% of the mites that died did so because they were infected with Metarhizium.

All very encouraging … but note I was very careful with my choice of words in that last sentence. I’ll return to this point shortly.

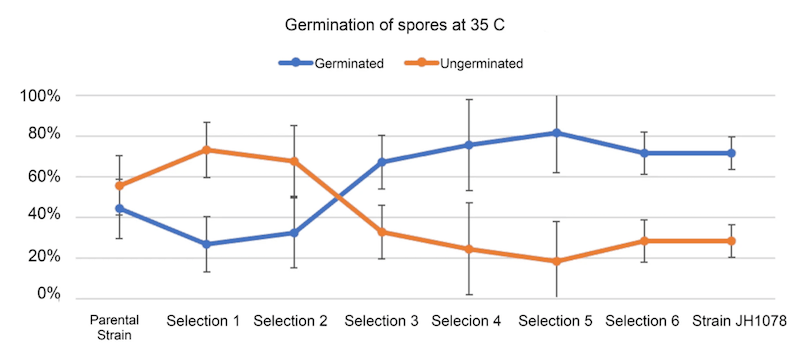

Before that, here’s the ‘proof’ that the strain selected by directed evolution (which they termed JH1078) possessed more thermostable spores.

They measured this by recording the percentage that germinated. At 35°C ~70% of JH11078 spores germinated compared to only ~45% of the M. brunneum F52 strain they started with.

But it’s not all good news

My carefully chosen “60% of the mites that died” neatly obscures the fact that you could get a significant increase in mites dying of Metarhizium, but still have almost all the mites in the hive surviving unscathed.

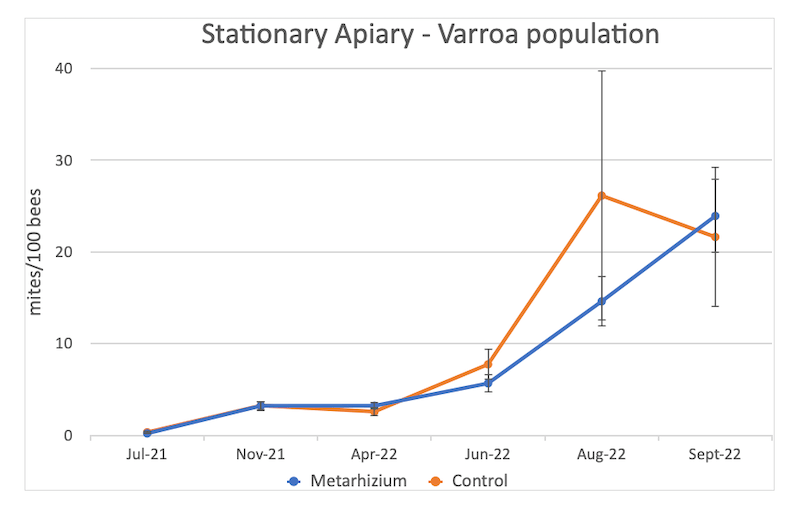

The authors continued repeated Metarhizium monthly treatments for a full season after the selection experiments described above. The apiary contained 48 colonies, 24 received Metarhizium JH1078 and the remainder received no treatment.

Did Metarhizium treatment stop the well documented increase in Varroa levels observed in colonies not treated with miticides?

Er … no.

They describe this data (above) as showing a ‘delay’ in the exponential increase in Varroa … but acknowledge that it ‘did not totally prevent it’.

Hmmm … looking at the error bars in the last few timepoints I’d be hard pressed to make the case that there was any significant difference in Varroa increase caused by treatment.

And while we’re here look at the mite infestation rate … 10-25 mites per 100 bees.

These are catastrophically high numbers and, unsurprisingly, 42 (~88%) of the 48 colonies – whether treated or untreated – died by the end of 2018, succumbing to “Varroa, pathogen pressure and intense yellow jacket predation”.

There was some evidence that colonies receiving Metarhizium treatment survived a bit longer than the untreated controls, but the end results were the same.

Almost every colony perished.

Metarhizium vs. oxalic acid

Typically a paper on a potential improved biocontrol method for Varroa would do a side-by-side comparison with a widely used, currently licensed treatment.

There’s only one comparative experiment between Metarhizium and dribbled oxalic acid treatment. It’s buried at the end of the Supplementary Data {{10}}. In it they show ‘no significant difference’ between the two treatments.

Frankly this was a pretty meaningless experiment … it was conducted in June 2020 when colonies would have been bulging with brood. Consequently 90% of the mites would have been hidden under the cappings. They assayed mite levels only 18 days after a single application of Metarhizium or oxalic acid.

Although it showed ‘no significant difference’ – like the “60% of the mites that died” quote – it obscures the fact that most mites were almost certainly completely untouched by either treatment.

What does this study show?

This study involved a large amount of work.

The directed evolution in the laboratory is a very nice example of how the combination of phenotypic selection and natural variation can rapidly yield new strains with desirable characteristics.

Combination of this with in vivo selection for enhanced pathogenesis successfully produced a novel strain of Metarhizium with some of the features desirable for biocontrol of Varroa.

However, in the apiary-based studies the majority of the colonies, whether treated or not, died.

This shows that, although scientists might have made a promising start, they are still a very long way from having an effective biocontrol solution for Varroa.

Unmanaged Varroa replicates to unmanageable levels

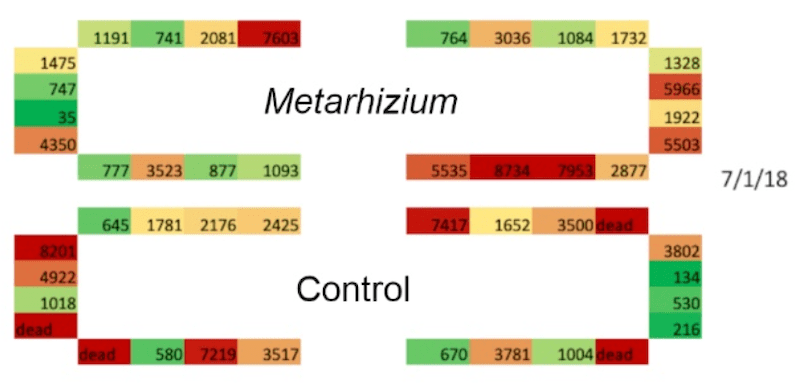

One of the Supplementary Data figures illustrated the Varroa drop per month from colonies in the research apiary.

This is relatively late in the study, July 2018. These hives were established from commercial packages of bees in April 2017. They were either treated with the experimental Metarhizium spores or were untreated controls for the 15 months between April 2017 and July 2018 {{11}}.

Look at those Varroa numbers!

This is the mite drop just after the peak of the season. Brood levels would be close to maximum in their short, warm summer {{12}}. The majority of the mite population would have been safely tucked away feasting on developing brood.

This is not the mite drop after miticide treatment … it’s just the drop due to bee grooming, natural mite mortality and the general ‘friction’ in the hive.

The average is 2866 mites dropped per month per hive 😥

Maybe nothing could have saved hives as heavily infested as these? {{13}}

Don’t wait for Metarhizium … be vigilant now

These numbers – of mites and dead colonies – are a stark warning of the replication potential of Varroa and the damage is causes our bees.

Left untreated, Varroa will replicate to very high levels.

Colony mortality – either directly due to the mite and viruses, or indirectly due to the weakened colonies succumbing to robbing – is a near-inevitable consequence.

I’ve discussed the importance of Varroa management repeatedly over the years. It’s a topic I’ll be returning to again – probably in August when it starts to become a necessity.

In the meantime, keep an eye on the mite levels in your own colonies as they get stronger during the season.

While you’re doing that think of the scientists who are looking for practical, effective and environmentally-friendly strategies to control Varroa. Understand that these studies are time-consuming, progress is glacial incremental … and they might not work anyway.

Of course, if we finally manage to develop a suitable Metarhizium-based mite control strategy then bees and beekeepers will not be the only beneficiaries.

Metarhizium has its own parasites. Some of the best characterised of these are small RNA viruses.

If beekeepers are sprinkling billions of Metarhizium spores over their colonies every year then these viruses will be having a great time 😉

{{1}}: Itself parasitised from Jonathan Swift’s satirical poem On Poetry: A Rapsody (1733).

{{2}}: Relatives of which also parasitise humans, causing amoeboid dysentery … there’s a pattern emerging here.

{{3}}: Or the domesticated or semi-domesticated animals that we care for and rely upon.

{{4}}: And it was really bad news for domesticated rabbits. It’s worth also noting that RHDV was introduced because myxoma virus was becoming less virulent and the rabbit population were increasingly resistant to myxomatosis.

{{5}}: From the Greek entomon, meaning insect, and pathogenic, meaning causing disease.

{{6}}: For an overview of some of the older literature perhaps look at Fungal biocontrol of Acari by a previous academic colleague of mine, Dr. David Chandler, University of Warwick, published in Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 10,357–384 (2000).

{{7}}: These are the vegetative branching growths of fungi … in contrast to the fleshy fruiting body which are best fried with bacon and eggs for breakfast.

{{8}}: Other than most of mine … perhaps we need a better publicity office?

{{9}}: Death by fungi … like Death by chocolate, but a lot less fun.

{{10}}: Additional information, but not really part of the main findings of the study.

{{11}}: There’s data for August and September, but it makes even more depressing reading.

{{12}}: The apiary was in Idaho.

{{13}}: Actually, there are strategies that work which I’ll discuss sometime in the future. Don’t ask, it’s one of those “I could tell you, but then I’d have to kill you” situations involving unpublished results and a PhD. student who has a very promising career ahead as long as I don’t give away all the secrets first.

Join the discussion ...