Midwinter chores

I was going to title this post ‘Midwinter madness’ until I realised that there’s nothing I could write about related to beekeeping that could compare with current political events. So, it’s Midwinter chores instead …

We’ve had a week or more of low temperatures with intermittent light snow, freezing rain and bright sunshine. During the latter I’ve escaped to walk in the local hills.

The North Fife hills – when they’re not filled with the cacophony of shooting parties out after pheasant or partridge – are looking fantastic, with unrestricted views to the Angus Glens, Schiehallion and Ben Lawers.

Of these, Schiehallion has a very distinctive shape (it’s just visible in the centre of the horizon above) {{1}}. Its isolation allowed Nevil Maskelyne to use it in 1774 to calculate the mass of the earth in the appropriately named Schiehallion experiment {{2}}.

This experiment used a combination of physics and mathematics, both of which are well beyond me, but are subjects I’ll return to at the end of the post.

Winter checks

In between these gentle walks I’ve infrequently checked all my colonies.

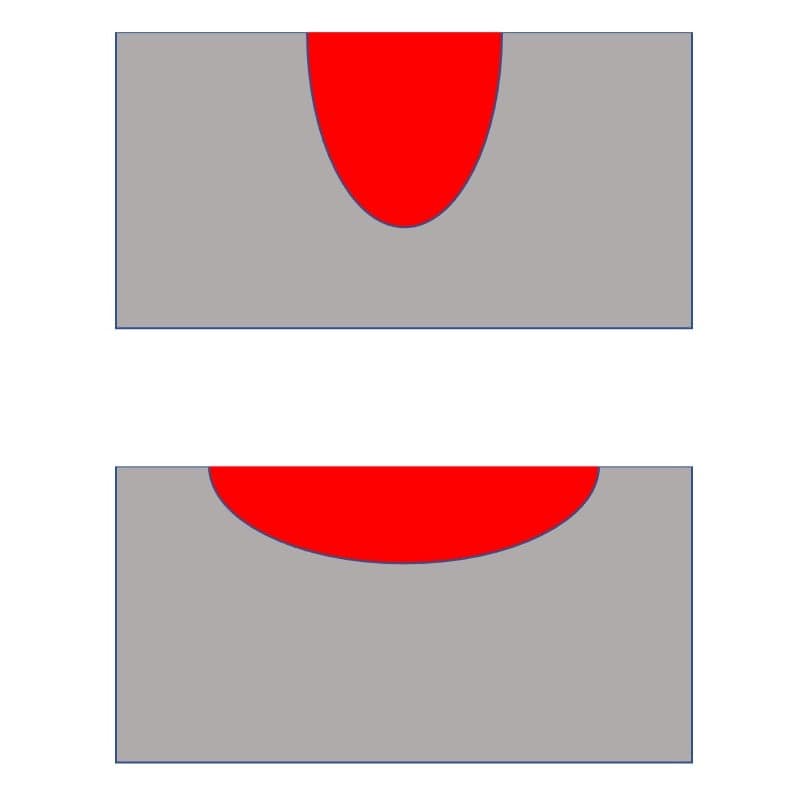

Many of my hives are fitted with clear perspex crownboards. This allows me to have a quick peek at the position and size of the winter cluster. Here are two examples:

and …

These hives are adjacent to each other in the same apiary. Both are in identical 10-frame Swienty poly brood boxes.

What is notable in the pictures above?

The first is that the crownboard with the mesh-covered central hole has been almost completely filled with propolis. I see this time and time again and am convinced that bees do not appreciate any ventilation over the cluster. I think the oft-seen advice to prop the crownboard up on matchsticks is total nonsense, at least for hives with open mesh floors.

Secondly, there is effectively no condensation on the underside of either crownboard. In the absence of ventilation – though both have my homemade open mesh floors – this is because they are both very well-insulated.

Insulation

Both crownboards are topped with a 5 cm thick block of Kingspan insulation. This is an integral part of the crownboard in #36, but just sits on top of #29. This insulation is present all year round, summer and winter.

Here is a picture of the same hives taken in October.

Hive #29 has one of my homemade Correx roofs. These cost me about £1.50 each and about 10 minutes to make. They provide negligible insulation as they’re only about 4 mm thick. However, as far as these hives are concerned this is irrelevant as it’s the underlying block of Kingspan that’s doing the insulation.

The £29 Abelo poly roof on #36, although undoubtedly a whole lot smarter, might add a bit more insulation, but it also made me a whole lot poorer 🙁

Cluster size

The cluster size in hive #36 appears significantly larger than that in hive #29. The area covered by bees under the crownboard is perhaps twice the size.

I don’t read a lot into this.

My notes suggest that hive #36 was a bit stronger towards the end of the summer season. Although it looks as though It’s on brood and a half, the super is actually nadired and was filled with partially capped frames that weren’t ripe enough to extract. I expect they are all now empty. However, the interrupted nature of my 2020 beekeeping meant there’s never been a good opportunity to recover the super.

It’s worth remembering that the bees visible under the crownboard now are not the same bees that were visible in late August, when I last inspected the colony.

These are the long-lived winter bees. Many of them will still be there in early March.

However strong the summer colony was, this is an entirely different population of bees.

Although I’m sure there’s a relationship between summer and winter colony strength, I bet it isn’t linear and I’m sure there are a number of things that can influence it.

For example, consider two identical summer colonies. One is treated with Apivar and the other with Apiguard. In my experience (I used Apiguard for 5 years before moving back to Scotland) the thymol-containing Apiguard inhibits many queens from laying for an extended period. If this occurs when the colony is rearing the winter bees then {{3}}, unless the queen (or colony) compensates {{4}} the final colony size will be smaller when compared with the Apivar-treated colony {{5}}.

Other things, like the age of the queen or the levels of pathogens, are known (or might be expected) to exert a significant effect on late season brood rearing, further emphasising that there isn’t a simple relationship between summer and winter colony size.

Cluster shape

It’s also worth noting that the orientation and organisation of the cluster will influence its appearance. Consider this picture:

The area (or volume if I could have drawn it in 3D) occupied by the cluster of bees in red is identical, but viewed from above, the diameter of the cluster in the top box would be half that of the cluster in the lower box {{6}}.

I’ve noticed before that hives with ample insulation over the crownboard often appear to contain unusually large winter clusters. I’ve always assumed that this is because the bees prefer to orientate themselves into the warmest, most energy-efficient shape to get through the winter.

This shape might need to change to allow access to stores as the winter progresses.

Remember that bees have evolved to occupy often oddly-shaped hollow trees. These might have thick and thin walled regions, or odd draughts, necessitating the reorganisation of the winter cluster to achieve the optimum energy efficiency.

Gaffer tape

The other thing to note from the photographs above is the parlous state of the second crownboard. Both the central mesh (now sealed up) and some of the wooden frame are held together with gaffer tape. This is a near-ubiquitous aspect of my beekeeping, and an essential inclusion in the bee bag.

With the exception of the Correx roofs I use the 3M duct tape sold cheaply in the ‘Middle of Lidl’. It’s great stuff, easy to tear with gloved hands, and pretty strong and sticky.

However, it’s not particularly waterproof. If you want gaffer tape to hold your roofs together for years then the Lidl stuff doesn’t ‘cut the mustard’. Instead use Unibond Waterproof Power Tape, which I’ve written about when discussing building Correx roofs. Mine have withstood the rigours of the Scottish climate for at least 6 years 🙂

Corpses

In discussing the winter bees (above) I wrote ‘many of them will still be there in early March‘.

Many, but not all.

Throughout the winter bees die. If the weather is too cold for flying these corpses simply accumulate on the floor of the hive.

With a strong colony and a prolonged period of cold or wet weather the number of corpses can be so numerous that there’s a danger the hive entrance will be blocked.

If that happens the undertaker bees will not be able to remove them when the weather picks up.

In fact, if that happens, no bees will be able to exit the hive.

Under normal conditions bees do not defecate in the hive. They store it all up during periods of adverse weather and then go on a cleansing flight when the weather improves.

But they cannot do this if the entrance is blocked. This can lead to rapid transmission of pathogens such as Nosema in the colony, with soiling of the frames and inside of the hive.

The L-shaped entrance tunnel of my preferred kewl floors can get blocked with corpses during very prolonged cold or wet periods {{7}}, and I’ve also seen it with reduced width entrances and mouseguards.

To avoid any problems I simply clear any corpses from the entrance using a bent piece of wire every fortnight or so. In my experience there’s no need to do it any more frequently than that.

Stores

Despite the intense cold, the Fife colonies now appear to be rearing brood. I’ve not opened the boxes, and have no intention of doing so just to confirm brood rearing. Instead I’ve infrequently monitored the Varroa trays left underneath the stands in the bee shed {{8}}. These now have faint stripes of biscuit-coloured capping crumbs, clear evidence that there is brood emerging.

And if there’s brood emerging they must have been fed (as developing larvae) on the stored honey from the hive.

Which means that the levels of stores available in the hive to get the colony through the remainder of the winter will be reducing.

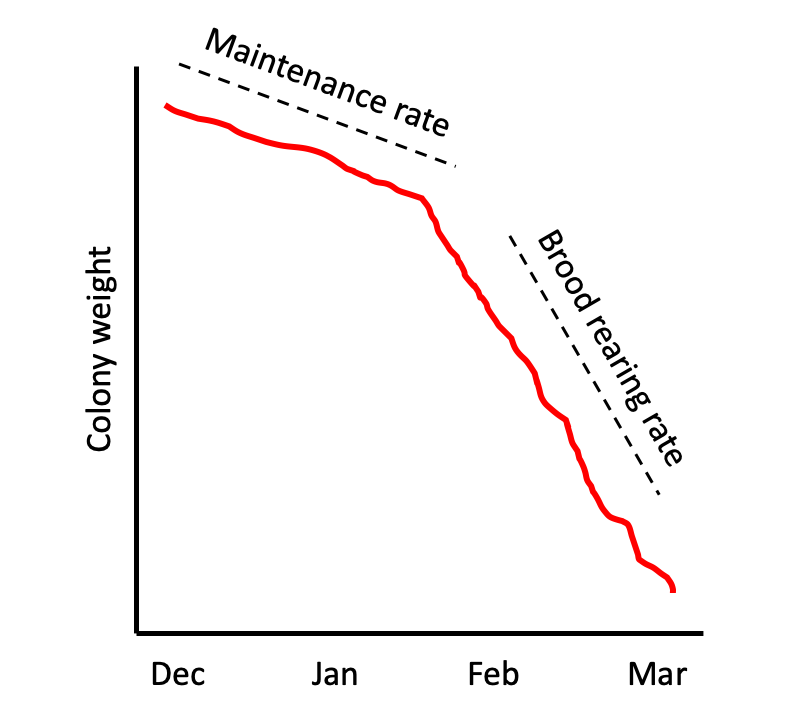

I’ve used this ‘no expense spared’ graph before to show how the rate at which stores are consumed increases once brood rearing starts.

Don’t read too much into the labelling on the horizontal axis. The point I’m trying to emphasise is that stores are used much faster once the colony starts rearing brood, not that the rate changes suddenly in mid/late January.

And, if there’s a lot of brood rearing happening over a prolonged period, there’s a possibility that the colony will run out of stores and starve.

This means that it is critical to monitor the weight of the hive in the early months of the year {{9}}.

Weighty matters

The goal is to determine whether the colony has sufficient stores to survive until forage becomes available.

Experienced beekeepers will do this by hefting the hive. This involves gently lifting the back {{10}} of the hive a centimetre or so and judging it’s weight.

This will then be compared with either (or both) the weight of a similar e.g. poly, cedar, single or double brood, empty hive or the weight of the same hive a week or two earlier.

As you might guess, this is a pretty inexact science 🙁

It really helps if all your hives are standardised … same material (cedar, poly), same number of brood boxes and the same type of roof.

However, the photo of the three hives (above) is pretty typical of my apiaries … different material, different roof and a different number of boxes.

D’oh!

Nevertheless, all I usually do is heft the hives.

As an alternative approach you can use a set of digital luggage scales. These can be used to weigh each side of the hive, again simply lifting it off the stand a centimetre or so until a stable reading is obtained. Add the two readings together and record them in your notebook.

This method has the advantage that you get an actual number to compare week to week, not some vague recollection of the ‘feeling’ of the colony and what you think it should weigh.

Popeye

But there’s a problem with using the digital luggage scales.

To obtain a reading stable enough to be recorded you need to lift the hive and hold it very steady. At least, that’s what is needed with the scales I purchased.

With luggage this is trivial. You just stand above the bag and lift it with a straight arm and … peep! … you have the weight.

But a hive on a hive stand means that the digital scales are probably already at thigh or hip height. Lifting 20-30 kg a short distance and holding it steady enough with a bent arm is very difficult.

At least it is if you don’t have forearms like Popeye or eat 2000 calories of protein shakes for breakfast before spending the morning doing benchpresses 🙁

Now you’re torquing

Which brings me back to maths and physics.

A comment on a post last season brought the eponymously named Fisher’s Nectar Detector (site permanently offline – James Fisher is a regular on Bee-L and might be contactable there) to my attention. This is a digital torque wrench adapted to read hive weights. They retail for about $130 in the US, but I don’t think they’re sold in the UK {{11}}.

The torque wrench is attached to a short L-shaped steel bracket that is inserted between the brood box and the floor of the hive. The weight is determined by gently applying torque, separating the box by a small distance and then lowering it again.

Although I don’t like the idea of separating the floor and the brood box, I’m intrigued by the advantages this method might offer. I also see no reason why you couldn’t lift the back of the hive from the hive stand, much in the same way as you manually heft a hive.

But the digital wrenches available here (for ~£25-50) record torque (e.g. Newton-metres), not weight. Converting one to the other isn’t difficult if you have a good understanding of basic physics.

I don’t … 🙁

But I think the Professor of Mechanics in the School of Physics might 😉

I’ll keep you posted.

{{1}}: As an aside … if you’re interested in the panoramas visible from particular viewpoints (around the globe) I recommend having a look at viewfinderpanoramas.org which has a large number available to download.

{{2}}: He actually calculated the mean density of the earth which he determined was significantly greater than that of Schiehallion. Maskelyne therefore concluded that the centre of the earth was very dense and likely metallic. As if this wasn’t enough, he went on to calculate the densities of the major objects in the solar system.

{{3}}: Which, typically, is when the treatment is used, after removal of the summer honey.

{{4}}: By laying for longer, or increasing her laying rate.

{{5}}: Whilst this would be an interesting experiment to try, the temperatures needed for Apiguard mean it’s ineffective in a typical Scottish autumn so I won’t be doing the study.

{{6}}: And, if my use of πr2 is correct, the area occupied 25% of the lower box.

{{7}}: These floors do not need mouseguards as the L-shaped tunnel prevents the mouse accessing the hive.

{{8}}: See the image a fortnight ago.

{{9}}: If the colony is getting dangerously light before the end of the year, rather than the early months of the following year, it suggests to me that it had insufficient stores at the end of the season.

{{10}}: Or side … the point is the hive stays on the stand and only one side is lifted.

{{11}}: If they are or, even better, if you have one and could comment, please correct me.

Join the discussion ...