Mellow fruitfulness

Synopsis : Final colony inspections and some thoughts on Apivar-contaminated supers, clearing dried supers, feeding fondant and John Keats’ beekeeping.

Introduction

The title of today’s post comes from the first line of the poem ’To Autumn’ by John Keats:

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness

The poem was written just over 200 years ago and was the last major work by Keats (1795-1821) before he died of tuberculosis. Although it wasn’t received enthusiastically at the time, To Autumn is now one of the most highly regarded English poems.

The poem praises autumn, using the typically sensuous imagery of the Romantic poets, and describes the abundance of the season and the harvest as it transitions to winter.

That’s as maybe … the last few lines of the first verse raises some doubts about Keats’ beekeeping skills:

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

It’s certainly true that there are late summer flowers that the bees can forage on {{1}}. However, he’s probably mistaken in suggesting that the bees think in any sense that involves an appreciation of the future.

And what’s all this about clammy cells?

If there’s damp in the hive in late summer then it certainly doesn’t bode well for the winter ahead.

Clammy is now used mean damp; like vapour, perspiration or mist. The word was first used in this context in the mid-17th Century.

But Keats is using an earlier meaning of ’clammy’ … in this case ’soft, moist and sticky; viscous, tenacious, adhesive’, which dates back to the late 14th-Century.

And anyone who has recently completed the honey harvest will be well aware of how apt that definition is 😉 … so maybe Keats was a beekeeper (with a broad vocabulary).

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies

That’s the last line of ’To Autumn’ (don’t worry … you’ve not inadvertently accessed the Poetry Please website). The swallows are gathering and, like most summer migrants, already moving south. Skeins of pink-footed geese have started arriving from Iceland and Greenland.

My beekeeping over the last fortnight has been accompanied by the incessant, plaintive mewing of buzzards. These nest near my apiaries and the calling birds are almost certainly the young from this season.

A few nights ago, while hosing the extractor out in the bee-free-but-midge-filled late evening, I was serenaded by tawny owls as the adults evicted their young from the breeding territory in preparation for next season.

These are all signs, together with the early morning mists, that summer is slipping away and the autumn is gently arriving.

The beekeeping season is effectively over and all that remains is preparing the colonies for winter.

Supers

All the supers were off by the 22nd of August. There was still a little bit of nectar being taken in but the majority was ripe and ready. As it turns out there was fresh nectar in all the colonies when I checked on the 10th of September, but in such small amounts – no more than half a frame – that it wouldn’t have been worth waiting for.

At some point you have to say … enough!

Or, this year, more than enough 🙂 .

Most of the honey was extracted by the end of August. It was a bonanza season with a very good spring, and an outstanding summer, crop. By some distance the best year I’ve had since returning to Scotland in 2015.

Of course, that also meant that there were more supers to extract and return and store for the winter ahead.

Lots of lifting, lots of extracting and lots of buckets … and in due course, lots of jarring.

Storing supers wet or dry?

In response to some recent questions on storing supers wet or dry I tested ‘drying’ some.

I’ve stored supers wet for several seasons. I think the bees ‘like’ the heady smell of honey when they are added back to the hives for the spring nectar flow. The supers store well and I’ve not had any problems with wax moth.

However, this year I have over two full carloads of supers, so – not having a trailer or a Toyota Hilux {{2}} – I have to make multiple trips back to put them in storage {{3}}. These trips were a few days apart.

I added a stack of wet supers to a few hives on the 1st of September and cleared them on the 9th. All these supers were added over an empty super (being used as an eke to accommodate a half block of fondant – see below) topped with a crownboard with a small hole in it (no more than 2.5 cm in diameter, usually less).

When I removed the supers on the 10th they had been pretty well cleaned out by the bees. In one case the bottom super had a very small amount of fresh nectar in it.

So, 7-8 days should be sufficient for a strong colony to clean out 3-4 supers and it appears as though you can do it at the same time as feeding fondant … result 🙂 .

Feeding fondant

I only feed my colonies Baker’s fondant. I add this on the same day I remove the honey-laden supers. I’ve discussed fondant extensively here before and don’t intend to rehash the case for its use again.

Oh well, if you insist 😉 .

I can feed a colony in less than two minutes; unpacking the block, slicing it in half and placing it face down over a queen excluder (with an empty super as an eke) takes almost as much time to write as it does to do.

But speed isn’t the only advantage; I don’t need to purchase or store any special feeders (an Ashforth feeder costs £66 and will sit unused for 49 weeks of the year). I’ve also not risked slopping syrup about and so have avoided encouraging robbing bees or wasps.

I buy the fondant through my association. We paid £13 a block this year (up from about £11 last year). That’s more expensive than making or buying syrup (though not by much) and I don’t need to have buckets or whatever people use to store, transport and distribute syrup. Fondant has a long shelf life so I buy a quarter of a ton at a time and store what I don’t use.

And, contrary to what the naysayers claim, the bees take it down and store it very well.

What’s the biggest problem I’ve had using fondant?

The grief I get when I forget to return the breadknife I stole from the kitchen … 😉 .

Apivar-contaminated honey and supers

Last season I had to treat a colony with Apivar before the supers came off. This was one of our research colonies and we had to minimise mite levels before harvesting brood.

I’ve had a couple of questions recently on what to do with supers exposed to Apivar … this is what I’ve done/will do.

The Apivar instructions state something like ’do not use when supers are present’ … I don’t have a set of instructions to check the precise wording (and can’t be bothered to search the labyrinthine VMD database).

Of course, you’re free to use Apivar whenever you want.

What those instructions mean is that honey collected if Apivar is in the hive will be ’tainted’ and must not be used for human consumption.

But, it’s OK for the bees 🙂 .

So, I didn’t extract my Apivar-exposed supers but instead I stored them – clearly labelled – protected from wasps, bees and mice.

This August, after removing the honey supers I added fondant to the colonies. In addition, I added an Apivar-exposed super underneath the very strongest colonies – between the floor and the lower brood box.

I’ll leave this super throughout the winter. The bees will either use the honey in situ or will move it up adjacent to the cluster.

In spring – if I get there early enough – the super will be empty.

If I’m late they may already be rearing brood in it 🙁 … not in itself a problem, other than it means I’m flirting with a ridiculous ’double brood and a half’.

Which, of course, is why I added it to the strongest double brood colonies. It’s very unlikely the queen will have laid up two complete boxes (above the nadired super) before I conduct the first inspection.

But what to do with the now-empty-but-Apivar-exposed supers?

It’s not clear from my interpretation of the Apivar instructions (that I currently can’t find) whether empty supers previously exposed to Apivar can be reused.

WARNING … my reading might be wrong. It states Apivar isn’t to be used when honey supers are on but, by inference, you can use and reuse brood frames that have been exposed to Apivar.

Could you extract honey from brood frames that have previously (i.e. distant, not immediate, past) been Apivar-exposed?

Some beekeepers might do this {{4}}.

It’s at this point that some common sense it needed.

Just because re-using the miticide-exposed supers is not specifically outlawed {{5}} is it a good idea?

I don’t think it is.

Once the bees have emptied those supers I’ll melt the wax out and add fresh foundation before reusing them.

My justification goes something like this:

- Although amitraz {{6}} isn’t wax-soluble a formamidine breakdown product of the miticide is. I have assumed that this contaminates the wax in the super.

- I want to produce the highest quality honey. Of course this means great tasting. It also means things like wings, legs, dog hairs and miticides are excluded. I filter the honey to remove the bee bits, I don’t allow the puppies in the extracting room and I do not reuse supers exposed to miticides.

- During a strong nectar flow bees draw fresh comb ‘for fun’. They’re desperate to have somewhere to store the stuff, so they’ll draw out comb in a new super very quickly. Yes, drawn comb is precious, but it’s also easy to replace.

Final inspections

I conducted final inspections of all my colonies in Fife last weekend {{7}}.

For many of these colonies this was the first time they’d been opened since late July. By then most had had swarm control, many had been requeened and all were busy piling in the summer nectar.

Why disturb them?

The queen had space to lay, they weren’t likely to think about swarming again {{8}} and they were strong and healthy.

Midsummer inspections are hard work … lots of supers to lift.

If there’s no need then why do it?

Of course, some colonies were still busy requeening, or were being united or had some other reason that did necessitate a proper inspection … I don’t just abandon them 😉 .

But now the supers were off it was important to check that the colonies were in a suitable state to go into the winter.

I take a lot of care over these final inspections as I want to be sure that the colony has the very best chance of surviving the winter.

I check for overt disease, the amount of brood in all stages (BIAS; so determining if they are queenright) and the level of stores.

And, while I’m at it, I also try and avoid crushing the queen 🙁 .

Queenright?

I don’t have to see the queen. In fact, in most hives it’s almost impossible to see the queen because the box is packed with bees. If there are eggs present then the queen is present {{9}}.

But, there might not be a whole lot of eggs to find.

Firstly, the queen is rapidly slowing down her egg laying rate. She’s not producing anything like 1500-2000 eggs per day by early autumn.

A National brood frame has ~3000 cells per side. If you find eggs equivalent in area to one side of a brood frame she’s laying at ~1000/day. By now it’s likely to be much less. At 500 eggs/day you can expect to find no more than half a frame of eggs in the hive.

Remember the steady-state 3:5:13 (or easier 1:2:4) ratio of eggs to larvae to pupae? {{10}}

Several of my colonies had about half a frame of eggs but significantly more than four times that amount of sealed brood … clear evidence that the laying rate is slowing dramatically.

The shrinking brood nest – note the capped stores and a little space to lay in the centre of the frame

Secondly, the colony is rapidly filling the box with stores, so reducing the space she has to lay. They’re busy backfilling brood cells with nectar.

Look and ye shall find …

So I focus carefully on finding eggs. I gently blow onto the centre of the frames to move the bees aside and search for eggs.

In a couple of hives I was so focused on finding eggs that – as I prepared to return the frame to the colony – I only then saw the queen ambling around on the frame. D’oh!

Some colonies had only 3-4 frames of BIAS, others had lots more though guesstimating the precise area of brood is tricky because of the amount of backfilling taking place.

I still need to check my notes to determine whether it’s the younger queens that are still laying most eggs … I’d not be surprised.

Stores

Boxes are now heavy but not full. All received (at least) half a block of fondant in late August and more last weekend. There’s also a bit of late nectar. The initial half block was almost finished in a week.

Once the bag is empty I simply peel it away from the queen excluder. If you’re doing this, leave the surrounding super in place. It acts as a ‘funnel’ to keep the thousands of displaced bees in the hive rather than down your boots and all over the floor.

Although the bees were flying well, the bees in and around the super were pretty lethargic. I’ve seen this before and am not concerned. I don’t know whether these are bees gorged with stores, having a kip or perhaps young bees that don’t know their way about yet. However, it does mean that any bees dropped while removing the bag tend to wander aimlessly around on the ground.

I’d prefer they were in the hive, out of the way of my size 10’s.

If you look at many of the frames in the hive they will be partially or completely filled with stores. The outer frames are likely to be capped already.

These frames of stores are heavy. There’s no need to look through the entire box. I simply judge the weight of each frame and inspect any that are lighter than a full frame of stores.

Closer to the brood nest you’ll probably find a frame or two stuffed, wall-to-wall, with pollen. Again, a good sign of a healthy hive with the provisions it needs to rear the winter bees and make it to spring.

Disease

The only sign of disease I saw was a small amount of chalkbrood in one or two colonies. This is a perennial situation (it’s not really a problem) with some of my bees. Quite a few of my stocks have some (or a lot of) native Apis mellifera mellifera genes and these often have a bit of chalkbrood.

I also look for signs of overt deformed wing virus (DWV) damage to recently emerged workers. This is the most likely time of the year to see it as mite levels have been building all season and brood levels are decreasing fast. Therefore, developing brood is more likely to become infested and consequently develop symptoms.

Fortunately I didn’t see any signs of DWV damage and the initial impression following the first week or so of miticide treatment is that mite levels are very low this season. I’ll return to this topic once I’ve had a chance to do some proper counts after treating for at least 8-10 weeks (I use Apivar and, since my colonies all have medium to good levels of brood, the strips need to be present for more than the minimum recommended 6 weeks).

Closing up

Although these were the last hive inspections, they weren’t the last time I’ll be rummaging about in the brood box.

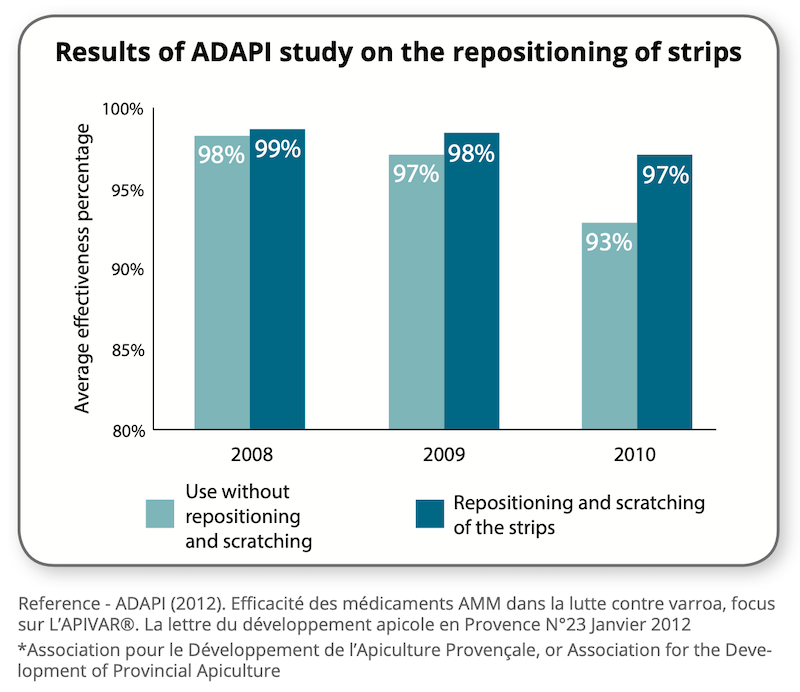

At some point during the period of miticide treatment I’ll reposition the strips (adjacent to the ever-shrinking brood nest) having scraped them to maximise their effectiveness.

However, all that will happen in a month or so when I can be reasonably sure the weather will be a lot less benign. Far better to get the inspections out of the way now, just in case.

So, having added the additional fondant (typically half a block) I closed the hives, strapped them up securely and let them get on with making their preparations for the coming winter.

Goodbye and thanks for the memories

There’s a poignancy about the last hive inspections of the season.

The weather was lovely, the colonies were strong and flying well, and the bees were wonderfully placid. It’s been a great season for honey, disease levels are low to negligible and queen rearing has gone well {{11}}.

But it’s all over so soon 🙁 .

Hive #5 (pictured somewhere above … with the empty bag of fondant) was from a swarm control nuc made up on the last day of May (i.e. a 2021 queen). It was promoted to a full hive in mid-June. At the same time, while the hive they came from (#28) was requeening I’d taken more than 20 kg of spring honey from it. The requeening of #28 took longer than expected as the first was almost immediately superseded. Nevertheless, the two hives also produced almost 4 full supers (conservatively at least 40 kg) of summer honey.

Good times 🙂 .

My notes – for once – are comprehensive. Over the long, dark months ahead I’ll be able to sift through them to try and understand better {{12}} what went wrong.

That’s because – despite what I said in the opening paragraph of this section – there were inevitably any number of minor calamities and a couple of major snafu’s.

Or ’learning opportunities’ as I prefer to call them.

But that’s all for the future.

For the moment I have a sore back and aching fingers from extracting for days and the memory of a near-perfect final day of proper beekeeping.

It’s probably time I started building some frames 🙁

{{1}}: Though Himalayan balsam would have been unknown to Keats as it wasn’t introduced to the UK until 1839.

{{2}}: Or a matter transporter.

{{3}}: Regular readers know I live on the west coast of Scotland, but have some bees on the east coast. I do all my extractions at home on the west coast.

{{4}}: Though not me as I never extract from brood frames.

{{5}}: See WARNING above … that’s my reading/interpretation and I’ve been wrong many, many, many times before.

{{6}}: The active ingredient in Apivar.

{{7}}: Those on the west coast are just mopping up the last of the nectar from the heather, so will be dealt with next week.

{{8}}: And if the cheeky blighters did try the queens were clipped so it wouldn’t be the end of the world.

{{9}}: Yes, yes, unless they recently swarmed … but it’s early September in Scotland and there are no queen cells, so they have not swarmed. The queen is in there if I can see some eggs. End of.

{{10}}: If not, why not? Do you think I write this stuff for fun?

{{11}}: At least on the east coast … I’ll recount some west coast horror stories when I’m finished with my therapist.

{{12}}: Perhaps ‘better’ is superfluous in this sentence.

Join the discussion ...