It's an ill wind

In late January Storm Éowyn rampaged through central Southern Scotland, leaving a trail of destruction behind her {{1}} and toppling several of my hives. The storm was followed by a night of freezing rain, conditions not unusual for Scotland, but far from ideal for bees trapped in a box in which the open mesh floor has been temporarily converted into an open mesh wall.

Or worse, roof.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm there was little point in doing anything other than righting the hives, strapping everything back down and hoping for the best.

Perhaps interleaved with a little self-criticism for not choosing a sheltered apiary, or failing to deploy sufficient straps and paving slabs to keep everything upright and secure.

Spilt milk, as they say.

In some of the boxes I'd seen bees moving around, not with any enthusiasm or purpose.

Or, for that matter, speed.

Nevertheless, there were some live bees in these boxes, so I was reasonably hopeful. However, my priority had been righting the boxes, not looking for survivors, and so I'd not checked for signs of life in every box.

I'd made a return visit to check up on the hives when delivering honey in the middle of February. Unfortunately, the weather was miserable, and so I'd done nothing more than heft the hives, add fondant to a couple of them and check the entrances were clear with my custom-made bent-wire-on-a-stick 'entrance clearer' {{2}}

Sunshine

But last weekend, on a return visit to deliver more honey, the weather was brighter and appreciably warmer. Not 'shirt-sleeves weather' or anything close, but warm enough that the bees were flying in the gusty wind, at least when the clouds weren't obscuring the sun.

The hive entrance activity was variable, even in full sun. Some hives were flying well, others were a bit half-hearted about things, and a couple were worryingly quiet.

In my experience, you get little or no activity at the hive entrance under the following conditions:

- a dead colony (no surprises there, but be aware that a dead colony can have activity at the entrance if robbing bees are clearing out any remaining stores),

- if the entrance is blocked with corpses {{3}},

- colonies that are queenless. At least in winter, these always seem to have much less entrance activity,

- sulky colonies. For whatever reason, some bees are very reluctant to fly if the conditions are marginal. Dark or native bee aficionados would suggest it's the tender Italian

wimpstypes that tend to sulk, staying home scoffing the stores, but I wouldn't be so presumptuous 😉.

I visited a couple of apiaries, checking to see that the hives had sufficient stores, adding more as needed, and peeking into a few hives where I thought it might be useful or informative.

I didn't inspect the colonies, instead just splitting the box in half and looking at the first central frame I hoicked out.

Goodbye, and thanks for the memories?

In one of the quiet boxes there were reasonable numbers of bees, together with a marked queen calmly walking about on one of the middle combs.

There was a queen … but no sign of eggs or brood.

This could be a sign of a failing (failed?) queen, or a failure on my part to remember my reading glasses.

I suspect the former, though the latter also applied.

There was little to be gained by looking through the rest of the box, so I closed it up and made a note to check it properly once the weather was better. Depending upon the numbers of bees remaining, if the colony is broodless in mid-March it's a dud, and I'll either shake the bees out or unite it with a strong hive (remember, these winter bees do lots of foraging in the early Spring … or would if they had a queen to work for).

A second colony in the same apiary, upended in Storm Éowyn and drenched in the subsequent freezing rain, was both quiet and — on cursory inspection — apparently queenless. However, there were still very good numbers of bees in the box, and they were getting through their stores. The weather was deteriorating, so I again postponed a closer inspection … why heap insult upon injury?

The other thing to note about winter colonies with missing, failed or failing queens, is that they consume their stores very slowly. With little or no brood to rear, and with the poor weather (and absence of flowers) preventing foraging, they just nibble it at a 'maintenance rate'.

You see the same thing in the autumn when preparing for winter. I usually find that colonies that don't take down their stores have some sort of queen problem e.g. a late mating that's failed. Better to unite them in the autumn, rather than let them linger on through the winter as they are inevitably doomed.

Windy weather

That January storm seems to have been the prelude to an extended period of high winds. As I write this it's gusting at ~45 mph, about 2–3 times the speed a bee flies at. However, it's only 8 °C, so only the occasional and most foolhardy bees are venturing forth from the nucs under my office window.

Whether they're getting back is unclear, and I'm not going to stand outside and count them.

Bees generally cope pretty well with the wind, showing alterations in their flight characteristics when foraging including greater hesitancy before take-off, and reducing the chance of impacting vegetation by flying faster and higher (in tailwinds, or the opposite in headwinds).

But strong winds influence other aspects of the honey bee life cycle, in particular queen mating {{4}}.

Now-penniless beekeepers who bought a copy of Koeniger et al's “Mating biology of honey bees (Apis mellifera)” will have read that:

[T]he minimal temperature for drone flight is around 18 °C while for queens it is about 20 °C [and] strong winds, cloudy skies and rain [will] prevent mating flight activity.

… which, at least for those of us living in Scotland, is clearly nonsense 😉.

Strong winds, cloudy skies and rain — or summer as we sometimes call it — might well prevent mating flight activity, but both drones and queens will fly and mate successfully in temperatures well-below 18 and 20 °C respectively.

Apiary vicinity mating

Queens usually undertake several relatively long distance flights to mate with drones in drone congregation areas. Drones fly less far, an arrangement that prevents inbreeding.

Using RFID-tagged queens, mating flights have been documented at temperatures as low as 14 °C, and there is a (perhaps surprising) inverse relationship between the number of flights taken and the temperature i.e. the queen makes more mating flights in cooler conditions.

One minor criticism of this study is that it was not known whether these low-temperature mating flights were successful.

To determine that you would have to prevent the queen from taking further flights. However, I'd argue that, if mating flights at low temperatures were routinely unsuccessful, evolution would have selected for queens with better temperature control, who would not have flown until the conditions were more suitable.

In more northerly and westerly areas, where conditions are even less likely to achieve those described by Koeniger, some bees exhibit modified mating flight behaviour and mate locally, in or around the apiary.

This is termed apiary vicinity mating (AVM). Dave Cushman (citing Boewulf Cooper) describes the process:

The queen emerges from the hive and is immediately followed by a number of drones from that hive, with one or more of which she mates within the confines of the apiary.

Jon Getty, who has witnessed it several times, states that:

The bees ‘float’ slowly around over the apiary in a circular pattern, and the process is silent, not like the frenetic hum you hear with an ordinary swarm.

Interestingly, he also states that he observes it on 'hot sunny days', which begs the question as to why the queen doesn't make her usual 4+ km flight.

Or, perhaps it means that Jon is only in the apiary on hot, sunny days …

Supersedure

Again, there may be an evolutionary explanation.

Inevitably, AVM means the queen is much more likely to be genetically related to the drones she mates with. In a one-hive apiary the queen would be mating with her brothers. This inbreeding, whilst reducing genetic diversity, results in retention of recessive genetic traits, some of which are beneficial.

One such trait is supersedure; this is the in situ replacement of the queen where the colony does not swarm, and with the two queens (the mother and daughter) often coexisting in the hive for weeks.

Supersedure is beneficial, at least under certain circumstances. These include environments where the weather is rarely be suitable for 'conventional' mating.

For example, a poorly mated queen resulting from a conventional summer mating flight is superseded in early autumn by her daughter. Since the conditions are even less likely to be suitable in early autumn for distant mating flights, a strain of bees that supersedes and practices AVM would be more likely to survive.

Disappointingly, I've never managed to observe AVM. I regularly loitered around my occupied mini-nucs when I lived on the remote west coast of Scotland, but — although I did see queen orientation flights — I never saw anything resembling the descriptions above.

Queen mating, particularly in 'high' summer, was always challenging and my dark, native bees exhibited quite high levels of supersedure.

I was almost certainly just in the 'wrong place at the right time'.

Again.

“Get out of jail free” cards

The Southern Cape regions of South Africa were once separated from the remainder of the African continent by sea. The ancestral honey bees that were present as the sea levels rose became isolated, and developed into a subspecies that were particularly well adapted to the naturally windy environment.

Unusually, female workers of this subspecies, Apis mellifera capensis (the Cape honey bee, which I'll abbreviate to capensis for convenience), have the ability to lay diploid eggs which develop into female progeny.

All other honey bees can exhibit so-called 'laying workers', but these workers lay haploid eggs which, being unfertilised, develop into drones.

In colonies other than capensis, laying workers are a last gasp evolutionary adaptation — a 'get out of jail free' card if you like — to the colony becoming terminally queenless.

With no queen, there are no eggs or larvae to rear into a new queen. The colony is doomed, but the drones reared from laying workers at least have the chance to pass on the genes from the colony … the bees might not survive, but the genes will.

But capensis workers — through a bit of genetic trickery termed automixis with central fusion which I have no intention of discussing further {{5}} — produce diploid eggs which develop into female progeny.

If reared under the correct (dietary) conditions these capensis females develop into queens.

It is thought that thelytokous (female birth) parthenogenesis evolved in capensis living in the windy fynbos regions of the Western and Eastern Cape to compensate for the high proportion of queens lost during mating flights.

A queenless capensis colony has a 'get out of jail free' card that trumps those of other honey bees.

If they lose the queen they can always replace her.

So far, so good …

Unintended evolutionary consequences

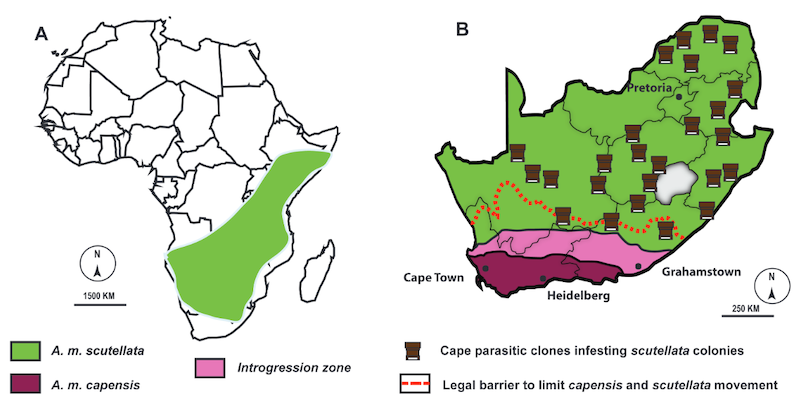

Capensis is naturally restricted to the two southern provinces of South Africa, but occupies a stable range that overlaps (by about 200 km) with another African subspecies, Apis mellifera scutellata.

In capensis colonies there may be laying workers as well as a laying (true) queen. The laying workers have even evolved to produce a queen-like mandibular gland pheromone bouquet, and 'worker policing' (whereby workers cannibalise eggs not laid by the queen) is not properly functional due to the genetic relatedness of the worker-laid offspring and those of the queen.

However, there's a trade-off between laying worker activity and colony fitness. Essentially, the more capensis laying workers there are in the colony, the less brood is reared. That's because capensis laying workers are not very good workers, and they don't contribute to hive activities.

Nevertheless, capensis colonies can be productive honey-producing units, and so are used by bee farmers in the southern provinces of South Africa.

And (are we surprised?) once humans start meddling, problems can arise.

Social parasitism and the 'capensis calamity'

About 30 years ago, migratory beekeepers moved hundreds of capensis colonies across the hybrid zone, further north into South Africa, an area previously solely occupied by scutellata bees.

Inevitably, some capensis workers drifted into neighbouring scutellata colonies. Normally, thanks to worker policing {{6}}, any eggs laid by capensis laying workers would be promptly removed by the host colony scutellata's workers.

Unfortunately, one {{7}} capensis worker carried a genetic mutation that made her eggs unrecognisable to the worker policing activities of the host scutellata colony.

And, as if that wasn't enough, additional studies showed that this clone of capensis workers activate their ovaries within a week of entering a scutellata colony (ovary activation is usually suppressed by pheromones produced by the queen, which is why there are so few laying workers in most queenright colonies), so becoming pseudoqueens.

The capensis progeny are preferentially nursed by the scutellata workers, emerge and rapidly become additional pseudoqueens.

The scutellata colony is inevitably doomed.

The scutellata queen is deposed (by mechanisms unknown) 1–50 days later, the capensis workers contribute little to hive activities, and the colony perishes 60–100 days after the initial infestation.

As Stephen Martin states {{8}} in the abstract to the paper (Martin et al., 2002) describing the absence of host colony worker policing:

This unique parasitism by workers is an instance in which a society is unable to control the selfish actions of its members.

Thousands of scutellata colonies were lost, and South African beekeepers continue to lose ~40% of colonies annually due to the 'capensis calamity' (Oldroyd, 2002, Mumoki et al., 2021).

There's lots more where that came from

I've barely scratched the surface of this fascinating topic.

This process has interesting molecular genetics (the single-gene that causes thelytokous parthenogenesis has recently been identified; Yagound et al., 2020) and even more interesting population genetics. Social parasitism is, or at least was a few years ago, a hot topic and is infrequently, but widely, observed.

The chemistry of pheromone production by reproductively dominant capensis workers, and the underlying biosynthetic pathways, has been extensively studied (Mumoki et al., 2021) and would make a long and totally incomprehensible post which I won't be writing any time soon.

From a historical perspective, the 1990s 'capensis calamity' was not unique. Records show it probably also occurred in 1928 and 1977. Both these events were self-limiting, possibly because of the reduced level of anthropogenic hive movements.

Attentive readers might be wondering about two things … at least, I hope they are.

- Why hasn't this social parasitism impacted the neighbouring scutellata colonies in the hybrid zone?

This is probably because these colonies have elevated levels of colony guarding activity, sufficient to repel drifting capensis workers.

- What's in it for the socially parasitic clone of capensis workers? Surely they'll die out as well?

Well, the colony probably dies (beekeepers term this process dwindling colony syndrome), but the capensis workers exhibit a high propensity to drift to other colonies. This is exacerbated by beekeeping activity, where parasitised colonies share an environment with scutellata colonies, where colonies are moved, or bees/frames are transferred. In addition, queenless capensis colonies abscond and are readily accepted in other hives in the same apiary.

A new beekeeper standing forlornly by a terminally queenless Apis mellifera colony, removing frame after frame containing dispersed bullet-shaped drone cells in worker comb {{9}}, might think the diploid laying worker activity of capensis — a likely adaptation to high winds — is a good thing.

Be careful what you wish for.

Why not sponsor The Apiarist?

If you're not already a sponsor, you're missing a lot. It costs less than £1/week annually, and ensures you can access every post.

If you are already a sponsor … thank you. Look out for something new on slow-release oxalic acid strips early next week.

Notes

But it’s an ill wind blaws naebody gude.

A quote from Sir Walter Scott's Rob Roy (1817) from which the phrase “It's an ill wind that blows nobody any good” originates (though there are similar, earlier, phrases with somewhat different interpretations), meaning that a wind that didn't provide benefit to someone would be unusual.

References

Martin, S.J., Beekman, M., Wossler, T.C., and Ratnieks, F.L.W. (2002) Parasitic Cape honeybee workers, Apis mellifera capensis, evade policing. Nature 415: 163–165 https://www.nature.com/articles/415163a.

Mumoki, F.N., Yusuf, A.A., Pirk, C.W.W., and Crewe, R.M. (2021) The Biology of the Cape Honey Bee, Apis mellifera capensis (Hymenoptera: Apidae): A Review of Thelytoky and Its Influence on Social Parasitism and Worker Reproduction. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 114: 219–228 https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/saaa056.

Oldroyd, B.P. (2002) The Cape honeybee: an example of a social cancer. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 17: 249–251 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169534702024795.

Yagound, B., Dogantzis, K.A., Zayed, A., Lim, J., Broekhuyse, P., Remnant, E.J., et al. (2020) A Single Gene Causes Thelytokous Parthenogenesis, the Defining Feature of the Cape Honeybee Apis mellifera capensis. Current Biology 30: 2248-2259.e6 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982220305479.

{{1}}: 'Her' because Éowyn is a fictional noblewoman in Tolkien's book The Lord of the Rings, and — in case, like me, you didn't know — is pronounced 'eh-OH-win'.

{{2}}: Patent pending, and soon to be available from my web store for an entirely reasonable £39.99 … in my dreams. It's actually a bicycle spoke 😉.

{{3}}: Can I interest you in my bent-wire-on-stick 'entrance clearer' at the special introductory price of £29.99?

{{4}}: Though not in early March, at least not where I live.

{{5}}: OK, since you insist; after the meiosis stage of cell division, diploidy is restored by the fusion of non-sister nuclei. A consequence of this process is that genetic recombination (mixing) is low; this is important, as it would otherwise contribute to inbreeding depression. It's not unique to capensis, and is also seen in some fungus-growing ants and the clonal raider ant.

{{6}}: Mentioned above, but this is something that really deserves a full post of its own.

{{7}}: It may have been several, but microsatellite analysis demonstrates that the socially parasitic capensis workers are all genetically clonal, and descended from a single parental worker.

{{8}}: Any implied reference to the current political situation is yours, and not mine.

{{9}}: The characteristic signs of laying workers activity.

Join the discussion ...