Is the honey ready?

Synopsis : How and when do you remove the supers to maximise the honey ready for extraction (and minimise the drudgery of extracting 😉 ). What is the ‘shake test’, and what do you do with frames that fail?

Introduction

Unless your bees are now up on the heather moors, or one or two other specific cases (e.g.ivy), the productive part of the beekeeping season is now more or less over.

Productive in terms of honey, queen and nuc production (or propolis, Royal Jelly etc.).

The days are shortening, it’s cooler in the mornings and – at least here in north-west Scotland – there’s the first hint of leaves changing colour on the trees.

Your hives should be full of bees. The drones – as discussed last week – are counting the days {{1}} or perhaps hoping {{2}} for one last chance at mating with a late virgin queen.

It’s not completely finished – and it depends upon where you live – but ’the end is nigh’. Of course, not an actual apocalyptical and eschatological event … just that most of the fun is over until next May 🙁 .

It didn’t last long did it?

Hopefully the hives are heavily laden with bulging supers 🙂 .

Colonies may start to get defensive if they’re being pestered by wasps or subjected to robbing by other colonies.

It’s about now that the beekeeper robs the hives of some or all of the summer honey and starts to make the all-important preparations for winter.

Summertime, and the livin’ is easy

About six weeks ago I wrote a post about the change in intensity of beekeeping once the swarm season is over. From then (late June or early July) until now I’ve pretty much stopped routine colony inspections. Visits to the apiaries are a lot more relaxed.

Most of the colonies have new queens (or I’m pretty certain that the 2020 or 2021 queens – all of which are clipped anyway – won’t swarm {{3}} ) and there is little to be gained from rummaging through the brood boxes.

What’s more, those supers are heavy 🙂 .

I’ve no interest in lifting off this lot …

… solely to (disruptively) confirm what I’m 98% certain of already i.e. that the queen is laying and has space to lay, that – nevertheless – the brood nest is contracting and they’re starting to backfill cells with nectar, that there’s enough pollen for the brood they are rearing and that there’s increasing (but still well within safe limits.{{4}}) numbers of mites in the colony.

Admittedly, I know some of these things because I’m familiar with the ’rhythm of the seasons’ here, having kept bees in eastern Scotland for several years.

That doesn’t mean I’ve abandoned beekeeping. Far from it.

Any boxes I’m unsure about have been regularly inspected. These include some with new queens and my hives on the west coast {{5}}.

Just this afternoon I found my last new laying queen of the season {{6}}. It’s been a shocking summer in the north-west, but she got out to mate in two days of half-decent weather last week.

The honey harvest

Most of my beekeeping has been in the Midlands and lowland Scotland. Neither area has heather and the only reliable late nectar sources are ivy and Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera).

Reliable in that there should be nectar available, not that the bees would reliably collect it.

In my experience ivy is usually too late for my bees in Scotland. Balsam is earlier, but is localised around rivers or damp ground.

In both cases, if the bees can get it, I let them keep any nectar they collect.

I therefore usually remove the honey supers soon after the main summer flow has finished. Last year that was the first week of August. All the supers were removed by about the 12th. This year – with fewer hives but a lot more supers 🙂 – I started removing full supers on the 1st of August and expect to have them all off by early next week {{7}}.

I know some beekeepers remove supers one at a time or as they’re filled and capped. With sufficient time and easy access to your hives that can work well.

However, most of mine are 140 miles away, I’m reasonably time-poor and – importantly – I consider extracting the third worst task in beekeeping {{8}}.

I therefore prefer to collect as many supers as possible in as short a period as practical. I stack them somewhere warm and then spend a day or two (or in a bad, so therefore antithetically, good year, three days) hunched over the extractor.

The sniff test

The water content of nectar can range between about 50 and 90%. Different nectars have different water content. Much of this water needs to be evaporated off by the bees or the resulting stored honey will ferment.

If you visit the apiary late on a calm summer evening you can hear the entire hive ‘humming’ as the bees fan their wings to create an airflow to evaporate the excess water off.

It often smells fantastic 🙂 .

Once the water content is low enough (less than 20%) the honey will not ferment and the bees usually seal the full cells with a wax cap.

However, it’s unusual that every frame in every super is capped. Many or most will be, but there are often frames – particularly the outside frames of a super – which are partially (or even completely) filled and not capped.

The super above is almost completely full, but the vast majority of the cells have not been capped.

Can it be extracted?

Will the honey ferment?

How can you avoid this situation in the first place?

So many questions … let’s go back to the apiary.

Checking the supers

Although I don’t lift off all those supers to inspect the brood boxes, I do periodically look at what’s going on in the supers.

With one or two supers and a clear crownboard you can usually see how the bees are getting on filling the frames without lifting anything but the roof.

If you add new supers to the top of the stack you can be reasonably sure that the lower supers will be more completely filled and better capped than the top one.

And, in case you’re wondering, it apparently doesn’t make any difference whether you add supers to the top or bottom of the stack.

So, if you top-super – and are over eight feet tall – you can check the stack as it grows without any lifting 😉 .

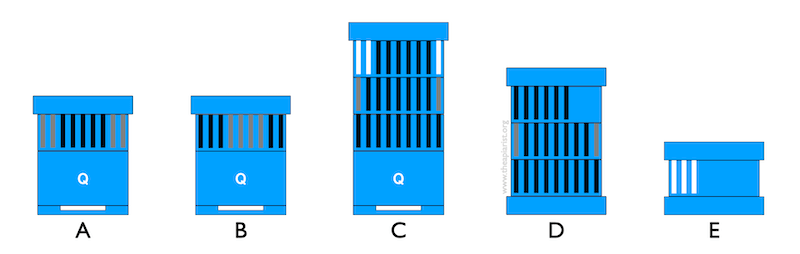

If the central frames are capped and the outer ones only part-filled/uncapped I swap them around (as shown in panel A and B, below, where black bars indicate capped frames and mid-grey bars indicate part-filled or uncapped frames).

Similarly, if the outside of the outer supers is being ignored I turn them round.

Evenly filled frames are easier to extract because they all weigh about the same so the extractor remains balanced.

My extractor takes 9 frames … and so do my supers 🙂 .

At least, they do once the comb is fully drawn.

I start the supers with 11 frames and foundation, but remove two once they’re drawn. The wider spacing encourages the bees to build deeper cells – more honey, less wax and (more importantly) less frames to extract.

However, don’t just start with 9 undrawn frames or the bees will probably build lots of brace comb in the big gaps between them.

Clearing supers

I’ve discussed clearing supers several times previously {{9}}. In my opinion the three important points are:

- use a clearer board with no moving parts (and avoid those abominable Porter escapes)

- make sure there is a gap below the clearer and above the box below the super being cleared

- that the supers of a queenright colony should be almost completely cleared within 12-16 hours

My clearer boards have a deep lower rim and two wide-spaced escapes. They work very well.

In the cartoon diagram above, panel C shows a hive with supers ready for clearing and removal.

The day after adding the clearer I remove the supers, leaving the clearer in place and undisturbed for the moment.

The supers are temporarily stacked in an upturned hive roof and covered with another roof – to keep them wasp and bee free.

If, as I remove the supers, I see bees that haven’t been cleared I drop the entire super {{10}} on an unoccupied hive stand to shake the stragglers off.

I then check individual supers. Those that are completely capped can be stacked – again with protection from robbing wasps and bees {{11}} – ready for transport.

Part capped super frames are subjected to …

The shake test

Honey with a water content lower than about 20% cannot be easily i.e. manually, shaken out of the cells. This is convenient because 20% is the upper limit {{12}} allowed for the sale of ‘honey’. Any higher than that and it’s likely that the honey will ferment (and therefore spoil).

Or it’s not ‘honey’ {{13}}.

Therefore, after removing the cleared supers you should test any frames that are partially or completely uncapped to confirm that the honey is ‘ripe’ and ready for extraction.

The ‘shake test’ takes just seconds to perform.

Hold the super frame horizontally by the side bars and give it a single sharp shake. If nectar flies out of the cells the water content of at least some of the uncapped cells on the frame is over 20%.

If, when you hold the frame horizontal – before shaking the frame – nectar drips or pours out of the cells then don’t even bother doing the shake test … the frame is not ready. Any frames like these, or any that fail the shake test, should be transferred into an empty super which can go back on the hive.

In the cartoon diagram above, the supers removed from the hive (C) included uncapped frames that passed the shake test (mid-grey and stacked with capped frames in D) and those that were insufficiently ripened which ended up in stack E.

Since there are almost no bees on these frames, you can mix’n’match the frames containing unripe honey from several hives.

Tidying up

I usually do the shake test over an inverted Correx roof. The dark colour makes it easy to see the drops of nectar that are shaken out. Doing it this way also means I don’t leave spilt nectar around the apiary that might induce robbing {{14}}.

Alternatively, you can shake the frames over the top of an opened hive. Since I try and clear all the supers in an apiary at once I prefer not have a hive open for the time it might take to check all the uncapped frames.

Once the supers are off, sorted, graded and stacked away ready for transport I shake the bees from the underside of the clearer and close the hives up, having placed the super(s) containing the frames of unripe honey on top of the strongest colony {{15}}. This is the most likely to ripen and cap the honey, or to use it for winter stores.

Preparation for winter

On the same day I remove the supers I often start the preparations for winter. I don’t want to write about this here (I’ve written about is previously and I don’t have the space) but it essentially involves:

- conducting a final inspection of the brood box

- adding Apivar, the miticide I usually use in late summer

- adding a 12.5 kg block of fondant

If the colony is healthy but weaker than I’d like, or not queenright, I would unite it with a strong colony. Far better to take your ‘losses’ in the autumn than in the winter.

But, back to those supers …

Having consolidated all of the extractable frames into the smallest possible number of boxes I then try and squeeze all 48 supers into the back of my little car and – yet again – wish I could sell enough honey to purchase a truck and trailer.

I must try harder 😉 .

Back at the ranch

Serious beekeepers have ‘warm rooms’ in which they stack the supers prior to extraction. This keeps the honey nicely warmed. It is therefore much easier to spin the honey out of the frames and it retards crystallisation.

I’m not a serious beekeeper 😉 .

But I do have a honey warming cabinet that I can stack a lot of supers on 😉 .

If you build your own honey warming cabinet it’s worth making it strong – joints glued and screwed etc.. There’s at least 200 kg of honey in the supers pictured above {{16}}. I would not try this with any of the commercial {{17}} honey warming cabinets I’ve seen (all of which are too small anyway).

The honey warming cabinet is set to 40°C and the supers are rotated, top to bottom and vice versa every day or two until I’m ready to extract.

It’s a lot of lifting, but the ease with which the honey is spun out makes it worthwhile {{18}}.

Spring honey from oil seed rape

The high glucose content of nectar from oil seed rape (OSR) means that the honey crystallises fast. Keeping it warm helps, but you still need to extract within a few days of getting the supers off the hive. In contrast, summer blossom honey often takes ages to crystallise, so you can deal with things in a more leisurely fashion.

Yikes! … wet frames at home

Sometimes a frame or two – or a super or two – of incompletely ripened honey sneaks through all those careful checks you conducted in the apiary.

You notice nectar dripping from a frame when you lift it out of the super … you give it a quick ‘shake test’ and a lot more nectar is shaken out.

What can you do with these frames or supers?

It rather depends how many of them there are and how much you want the honey.

But first … what you should not do is extract them and mix them with the high quality, low water content honey that forms the bulk of the stuff you are extracting. Doing this risks ruining an entire bucket {{19}}.

I think the choice is probably one of:

- returning the frames/supers to the apiary for the bees

- stacking the supers in a small warm room with a dehumidifier. If you do this, place spacers between the supers to encourage good airflow

- spinning out the ‘wet’ honey at low speed before uncapping the frames and extracting as normal. If you do this, make sure you empty the extractor and use the ‘wet’ honey as winter feed for the bees (or for mead)

I’ve only ever really done the first two of these. A dehumidifier works, but that was long ago when energy was cheap.

These days I’m much more rigorous in screening frames/supers in the apiary and any that slip through are returned to the bees {{20}}.

Points I failed to mention earlier

Inevitably I missed a few things I intended to cover, or remembered them too late to weave into the main part of the post … {{21}}.

Caveats

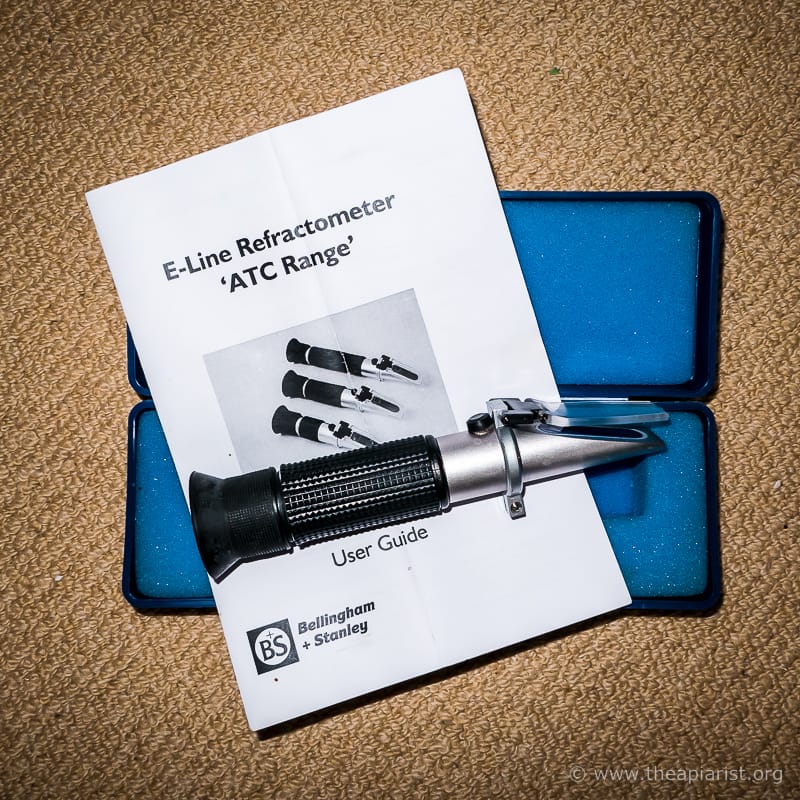

Remember … the ‘Can’t shake honey with less than 20% water out of a frame’ rule somewhat dependent upon how strong you are.

You should still test your extracted honey with a refractometer.

Brace comb

If you find the bees are building brace comb under the clearer you can be certain that the nectar flow is not finished yet (or another has started).

The clearer above was inadvertently left on for a few days, but they can build a surprising amount of new comb within 24 hours in a strong nectar flow. If this is the case you should expect many of the frames will not be ready for extraction.

Failed clearers

If your clearer doesn’t almost completely clear the supers overnight, either:

- it’s a lousy design and/or blocked with dead drones, or

- the colony is not queenright (it might be worth checking 😉 )

Returning supers for capping and/or stores

When returning supers with unripe stores for the bees I place them over the brood box (and queen excluder) if I want the bees to ripen and cap the honey. Obviously – at least it should be to anyone who reads the instructions – in this instance I don’t add Apivar, or start feeding for winter.

However, if I’m returning the super for the bees to store the nectar I nadir the super i.e. place it underneath the brood box. Any capped stores in the super are bruised by gently pushing down on the cappings. The damaged cells consequently weep small amounts of honey. Since the colony stores honey above and to the sides of the brood nest they usually empty the nadired super and move the honey up.

If the laying rate of the queen has slowed sufficiently she is unlikely to fill the nadired super with brood. Depending upon the time of the season you need to judge when to remove this nadired ‘super’ {{22}}, or whether to leave it on overwinter.

By the time you get to it in the spring it’s likely to have brood in 🙂 .

{{1}}: Of course, they’re doing nothing of the sort. I don’t believe that bees are sentient or that drones have any conception of their impending fate.

{{2}}: Er … ditto!

{{3}}: Though some may yet be superseded.

{{4}}: So no overt DWV-mediated disease

{{5}}: Where I’m still learning how the timing of the season differs.

{{6}}: At least, the last I’m expecting.

{{7}}: I’ve already taken one super off all the boxes in the first picture.

{{8}}: Only marginally better than cleaning the extractor, which – in turn – is an order of magnitude less fun than filling mini-nucs in the rain.

{{9}}: Here, for example.

{{10}}: From just a few inches … no higher or you risk breaking the frame lugs.

{{11}}: Not usually needed for the spring honey harvest, but almost essential in the summer.

{{12}}: For blossom honeys … for heather honey it’s 23%. At least, that’s my understanding of the 2015 honey regulations, but I strongly recommend you check yourself.

{{13}}: Formally it’s Baker’s honey up to 23% (25% for heather) and above that it’s still nectar!

{{14}}: The roof is subsequently used to stack supers on for transport.

{{15}}: Or colonies, depending upon the number of frames and supers.

{{16}}: The full supers weigh 17-21 kg each, making a total weight of over 300 kg.

{{17}}: But sold for amateur beekeepers.

{{18}}: ’It’ in this case being the fortune I have to spend on chiropractor appointments to fix my back.

{{19}}: Remember, depending where you sell your honey, a 15 kg bucket might be worth £300 … don’t risk it fermenting during storage or you’ll never be able to afford that truck and trailer.

{{20}}: I obviously don’t like spinning out the wet honey as I hate cleaning the extractor!

{{21}}: It’s 1.48 am on Friday morning. Give me a break!

{{22}}: Is a super under a brood box still a super? Tricky!

Join the discussion ...