Is queen clipping cruel?

Synopsis : Is clipping the queen a cruel and barbaric practice? Does it cause pain to the queen? Surely it’s a good way to stop swarming? This is an emotive and sometimes misunderstood topic. What do scientific studies tell us about clipped queens and swarming?

Introduction

After the contention-free zone of the last couple of weeks I thought I’d write something about queen clipping.

This is a topic that some beekeepers feel very strongly about, claiming that it is cruel and barbaric, that it causes pain to the queen and – by damaging her – induces supersedure.

Advocates of queen clipping sometimes recommend it as a practice because it stops swarming and is a useful way to mark the queen {{1}}.

I thought it would be worth exploring some of these claims, almost all of which I think are wrong in one way or another.

I clip and mark my queens.

You can do what you want.

This post is not a recommendation that you should clip your queens. Instead, it’s an exploration of the claimed pros and cons of the practice, informed with a smattering of science to help balance the more emotional responses I sometimes hear.

By all means do what you want, but if you oppose the practice do so from an informed position.

Having considered things, I believe that the benefits to my bees outweigh the disadvantages.

And I deliberately used the word ‘bees’ rather than ‘me’ in the line above … for reasons that should become clear shortly.

What is queen clipping?

Bees have four wings. The forewings {{2}} are larger and provide the most propulsive power.

Each wing consists of a thin membrane supported by a system of veins. The veins – at least the larger veins – have a nerve and a trachea running along them. Remaining ‘space’ in the vein is filled with haemolymph as the veins are connected to the haemocele.

Queen ‘clipping’ involves using a sharp pair of scissors to remove a third to a half of just one of the forewings.

Done properly – by which I mean cutting enough from one wing only whilst not amputating anything else (!) – significantly impairs the ability of the queen to fly.

She will still attempt to fly but she will have little directional stability and is unable to fly any distance.

It shouldn’t need stating {{3}} but it’s only sensible to clip the wing of a mated, laying queen.

Although you can mark virgin queens soon after emergence – before orientation and mating flights {{4}} – clipping her wing will curtail all mating activity {{5}}.

How to clip the queen

If I know I want to mark and clip a queen I find my Turn and Mark cage, Posca pen and scissors. The cage is kept close to hand, the pen and scissors are left in a semi-shaded corner of the apiary.

Then all you need to do is:

- Find the queen, pick her up and place her in the cage. Leave the caged queen with the pen/scissors while the frame is returned to the hive {{6}}.

- Holding the cage in my left hand and scissors in my right I gently depress the plunger and wait until she reverses, lifting one forewing through the bars of the cage. At that point I depress the plunger a fraction more to hold her firmly in place.

- Cut across the forewing to reduce its length by 1/3 to 1/2. Be scrupulously careful not to touch the abdomen with the scissors, or to sever a leg by accident {{7}}.

- Mark the queen with a single spot of paint on her thorax then leave the queen in the cage for a few minutes while the paint dries.

- Return the queen to the hive. The simplest way to do this is to remove the plunger and lay the barrel of the cage on the top bars of the frame over a frame of brood. The workers will welcome her and, in due course, she’ll wander out and down into a seam of bees.

Don’t real beekeepers just hold the queen with their fingers?

Probably.

Maybe I’m not a real beekeeper 😉

I prefer to cage the queen before clipping and marking her.

I wear nitrile or Marigold gloves (or one of each) to keep my fingers propolis free. If the gloves are sticky with propolis I don’t want this coating the queen. I also prefer to keep my scents and odour off the queen {{8}}.

The other reason I prefer to cage the queen is to reduce the potential for damaging her with the scissors.

You’d have to be even more cackhanded than me {{9}} to pierce the abdomen of a caged queen with the scissors. In addition, her ability to raise a hind leg up and through the bars of the cage is restricted. In contrast, when held in the fingers, both these can be more problematic.

Finally, briefly caging the queen allows me to use both my hands for other things – like completing the colony inspection without any risk of crushing the queen.

Yes, I could unglove before clipping and marking the queen, but it’s almost impossible to get nitriles back on if your hands are damp.

Does queen clipping stop swarming?

No.

Is that it? Nothing more to say about swarming?

OK, OK 😉

If the queen is not clipped the colony will typically swarm on the first suitable day after the new queen cell(s) in the hive are sealed. The swarm bivouacs nearby, the scout bees find and select a suitable new nest site and the bivouacked swarm departs – often never to be seen again – to set up home.

I’ll return to the subsequent fate of the swarm at the end of this post.

A colony with a clipped queen usually swarms – by which I mean the queen and up to 75% of the workers leave the hive – several days after the new queen cell(s) is capped.

Ted Hooper {{10}} claims a colony headed by a clipped queen “swarm(s) when the first virgin queen is ready to emerge” {{11}}. This is not quite the same as when the first virgin emerges.

Since queen development takes 16 days from the egg being laid this theoretically means you could conduct inspections on, at least, a fortnightly rota. Unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple as bees could choose an older larva to rear as a new queen.

Hooper has a page or so of discussion on why a 10 day inspection interval achieves a good balance between never losing a swarm and minimising the disturbance to the colony. {{12}}.

What happens when a colony with a clipped queen swarms?

A clipped queen cannot fly, so when she leaves the hive with a swarm she crashes rather unmajesterially {{13}} to the ground.

In my experience there are two potential outcomes:

- the bees eventually abandon her and return to the hive. Usually the queen will perish. They are still likely to swarm when the virgin queen(s) emerge. All together now … “queen clipping does not stop swarming”.

- the queen climbs the leg of the hive stand and often ends up underneath the hive floor. The bees join her. In this case you can easily retrieve the swarm together with the clipped queen. Temporarily set aside the brood box and supers and knock the clustered bees from underneath the floor into a nuc box.

I spy with my little eye … a clipped queen that swarmed AND was abandoned by the bees. It’s a tough life.

Sometimes both the queen and the swarm re-enter the hive (or I return them to the hive). In my experience these queens often don’t survive, presumably being slaughtered by a virgin queen.

So that addresses the swarming issue {{14}}. What about the more contentious aspect of queen clipping causing pain?

Do queens feel pain?

I discussed whether bees feel pain a couple of years ago. The studies on self-medication with morphine following amputation are relevant here. Those studies were on worker bees, but I’ve no reason to think queens would be any different {{15}}. I’m not aware of more recent literature on pain perception by honey bees though it’s well outside my area of expertise, so I may have missed something.

Therefore, based upon my current understanding of the scientific literature, I do not think that worker bees feel pain and I’m reasonably confident that queens are also unlikely to feel pain.

It’s worth noting here that it’s easy to be anthropomorphic here, particularly since we (hopefully) all care about our bees. Saying that your bees are happy, or grumpy or in pain, because it’s a nice day, or raining or you’ve just cut her wing off, are classic examples of ascribing human characteristics to something that is non-human.

We might think like that {{16}} but it’s a dangerous trap to fall into.

Is clipping queens cruel and barbaric?

According to my trusty OED, cruel means “Of conditions, circumstances: Causing or characterized by great suffering; extremely painful or distressing.”

Therefore, if clipping a queen’s wing causes pain and distress then it should be considered a cruel practice.

I’ve discussed pain perception previously (see above). If bees, including queens, do not feel pain then clipping her wing cannot be considered as cruelty.

Someone who is barbaric is uncultured, uncivilised or unpolished … which surely couldn’t apply to any beekeepers? In the context of queen clipping it presumably means a practise known to cause pain and distress.

Having already dealt with pain that brings me to ‘distress’.

How might you determine whether a queen with a clipped wing is distressed?

Perhaps you could observe her after returning her to the colony? Does she run about wildly or does she settle back immediately and start laying again?

Returning a marked and clipped queen – no apparent distress, just calmly disappearing into a seam of bees

But, let’s take that question a stage further, how would you determine that it was the clipped wing that was the cause of the distress? {{17}}

That pretty much rules out direct observation. Queens are naturally photophobic {{18}} so you’d need to use red light and an observation hive. I’m not aware that this has been done.

Instead, scientists have observed the performance of colonies headed by clipped and unclipped queens. I’d argue that this is a convenient and suitable surrogate marker for distress. You (or at least I) would expect that a queen that was in distress would perform less well – perhaps laying fewer eggs, heading a smaller colony that collected less honey etc.

Are clipped queens distressed? Is their performance impaired?

Which finally brings us to some science. I’ve found very little in the scientific literature about queen clipping, but there is one study dating back over 50 years from Dr I.W. Forster of the Wallaceville Animal Research Centre, Wellington, New Zealand {{19}}. I can’t find a photo of Dr. Forster, but there’s an interesting archive of photos from the WARC provided online from the Upper Hutt City Library.

Wallaceville Animal Research Centre staff photo 1972. Presumably Dr. Forster is somewhere in the group.

The paper has a commendably short 37 word results and discussion section 😉 {{20}}

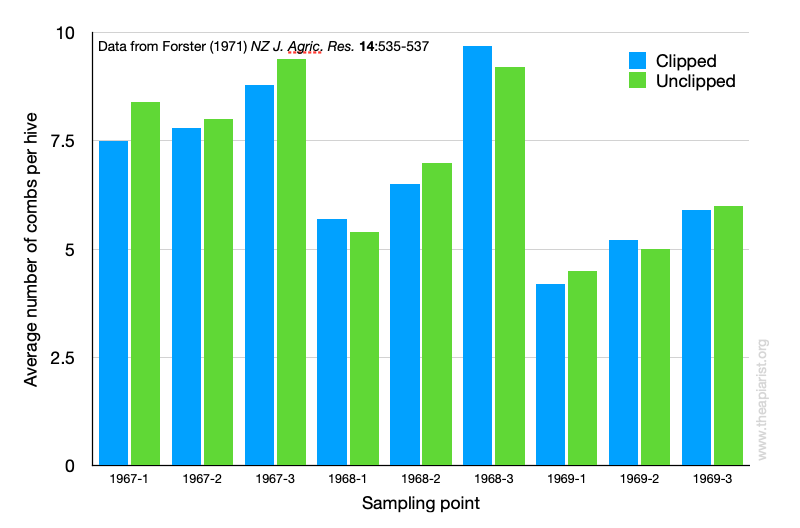

The study involved comparing performance of colonies headed by clipped or unclipped queens over three seasons (1968-1970), a total of 124 colony years. They {{21}} scored colony size (brood area), honey per hive (weight) and the the number of supersedures.

I’ll quote the single sentence in the results/discussion on honey production in its entirety:

There was no significant variation in honey production between hives headed by clipped and unclipped queens.

Forster {{22}} didn’t specifically comment on colony size/strength in the discussion. Had it differed significantly some convoluted explaining would have been needed to justify the similarity in honey production.

And it doesn’t.

Each column represents the average number of frames of brood in 6-29 colonies headed by clipped or unclipped queens. Statistically there’s no also difference in this aspect of performance (entirely unsurprisingly).

Colonies headed by clipped queens are not impaired in strength or honey production, so I think it’s reasonable to assume that the queen is probably not distressed.

Do clipped queens get superseded (more) frequently?

I suspect most beekeepers underestimate supersedure rates in their colonies.

I clipped and marked a queen last weekend. In early August last year my notes recorded her as ’BMCLQ’ i.e. a blue marked clipped laying queen {{23}}. In mid/late April this year she was unmarked and unclipped … and stayed that way until it was warm enough to rummage through the hive properly.

She’s now a YMCLQ {{24}} and was clearly the result of a late season supersedure.

Every spring I find two or three unmarked queens in colonies. Sometimes it’s because I’d failed to find and mark them the previous season. More usually it’s because they have been superseded.

The Forster study recorded supersedure of clipped and unclipped queens. It varied from 10-25% across the two seasons tested (’68 and ’69) and was fractionally lower in the clipped queens (20% vs. 22.5%) though the difference was not significant.

So, to answer the question that heads this section … yes, clipped queens do get superseded {{25}}. However, done properly they do not show increased levels of supersedure {{26}}.

Let’s discuss swarming again

In closing let’s again consider the fate of swarms headed by clipped or unclipped queens.

If a colony with the clipped queen swarms the queen will either perish on the ground, or attempt to return to the hive. If the swarm abandons her they will return to the hive … but may swarm again when the first virgin emerges.

If she gets back to the hive she may be killed anyway by a virgin queen.

You might lose the queen, but you will have gained a few days.

If a colony with an unclipped queen swarms … they’re gone.

Yes, you might manage to intercept them when they’re bivouacked. Yes, they might end up in your bait hive. But, failing those two relatively unlikely events, you’ve lost both the queen and 50-75% of the colony.

What is the likely fate of these lost swarms?

They will probably perish … either by not surviving the winter in the first place, or from Varroa-transmitted viruses the following season.

Studies by Tom Seeley suggest that only 23% of natural swarms survive their first winter. Furthermore, the survival rates of previously managed colonies that are subsequently unmanaged – for example, the Gotland ‘Bond’ experiment – is less than 5%.

Let’s be generous … a lost swarm might have a 1 in 4 chance of surviving the winter, but its chances of surviving to swarm again are very slim.

Anecdotal accounts of ’a swarm occupying a hollow tree for years’ are common. I’m sure some are valid, but tens of thousands of swarms are probably lost every season.

Where does that number come from?

There are 50,000 beekeepers in the UK managing 250,000 colonies. On average I estimate I lose swarms from 5-10% of my colonies a season, and my swarm control is rigorous and reasonably effective {{27}}. If there were over 25,000 swarms ‘lost’ a year in the UK I would not be surprised.

Free living colonies are not that common, strongly suggesting most perish.

Where do these ‘lost’ swarms go?

There are four obvious possibilities. They:

- voluntarily occupying a bait hive and become managed colonies

- occupy a hollow tree or similar ‘natural’ void

- set up a new colony in an ‘unnatural’ void like the roof space of a children’s nursery or the church tower

- fail to find a new nest site and perish

Of these, the first means that it’s likely the colony will be managed for pests and disease, so their longer term survival chances should be reasonably good.

In contrast, the survival prospects for unmanaged colonies are bleak. They will almost certainly die of starvation or disease.

What about the lost swarm that occupies the loft space in the nursery or the church tower? Whether they survive or not is a moot point (and the same arguments used for ‘bees in trees’ apply here as well). What is more important is that they potentially cause problems for the nursery or the church … all of which can be avoided, or certainly reduced, if the queen is clipped.

And if you conduct a timely inspection regime.

Why I clip my queens

Although it is convenient to reduce the frequency of colony inspections, that is not the main reason I clip my queens.

I clip my queens to help keep my worker population together, either to increase honey production or to provide good strong colonies for making nucs (or queen rearing).

This has the additional benefit of not imposing my swarms and bees on anyone else. Whilst I love my bees, others may not.

An additional, and not insignificant, benefit is that the prospects for survival of a ‘lost’ swarm are very low.

By reducing the loss of swarms I’m “saving the bees”.

More correctly of course, I’m preventing the loss of an entire colony. I think clipping queens is therefore an example of responsible beekeeping.

I also think queen clipping is acceptable as I’ve seen no evidence – from my own beekeeping or in the literature – that it is detrimental to the queen or the colony.

Thou shalt not kill

Finally, there are some that argue you should never harm or kill a bee. I have two questions in response to that view;

- What do you do with a queen heading up a truly psychotic colony? Do you kill her and replace her or do you put up with the aggravation and make the area around the hive a ‘no go zone’ for anyone not wearing a beesuit?

- How many beekeepers can honestly say that no bees are harmed when returning frames during an inspection, or putting heavy supers back on a hive? {{28}}

I would have no hesitation in killing and replacing a queen heading an aggressive colony.

Again, I think that’s responsible beekeeping.

Similarly, although I’m as careful and gentle as I can be when conducting inspections or returning supers, to think that no bees are ever injured or killed is fantasy beekeeping.

Note

This is an emotive topic and I’ve written far more than I’d intended – that’s due to a couple of days of rain and the ‘expectant father’ wait for my new queens to start laying. I could have written half as much again.

The time spent writing meant I’ve not done an exhaustive literature search. I know that Brother Adam wrote in 1969 that he’d clipped queens for over 50 years without noticing any disadvantages. I realised during the week that my American Bee Journal subscription has lapsed so I’ve not managed to go through back issues, though I have searched almost 30 years of correspondence on Bee-L. If an ABJ turns up more relevant information I’ll revisit the subject.

{{1}}: Left wing = odd year, right wing = even year … and, unlike paint, it cannot wear away. I’m not going to discuss this further as I also consider queen marking should be an aid to queen finding. And this isn’t.

{{2}}: Confused already? Please try to keep up!

{{3}}: But I will anyway.

{{4}}: Without reportedly reducing mating success rates, though this is not something I’ve done.

{{5}}: I’m not sure whether she then automatically becomes a drone laying queen, or if the colony disposes of her. Anyone?

{{6}}: Assuming it’s not a cold day I sometimes complete the hive inspection at this point.

{{7}}: See below.

{{8}}: Delightful though they might be – at least at the beginning of a hard day’s beekeeping on a hot day!

{{9}}: And there’s not a lot of leeway.

{{10}}: And, let’s face it, who am I to question such an authority?

{{11}}: Ted Hooper, Guide to Bees and Honey.

{{12}}: I’m not going to regurgitate it here and recommend you read it.

{{13}}: My spellchecker tells me that isn’t a word. It should be.

{{14}}: Time for another chorus … “queen clipping does not stop swarming”.

{{15}}: And, from an evolutionary standpoint, I think there’s even less chance that a queen would have evolved the ability to feel pain. They live in a totally protected environment for 99.9% of their lives.

{{16}}: And I’m as guilty as the next beekeeper … e.g my bees are ”happy and calm” because there’s a good nectar flow from the OSR.

{{17}}: Rather than the prior handling or the subsequent observation, for example.

{{18}}: You’ll usually find them on the reverse of the next frame you lift out of the hive … if they’re on that frame at all.

{{19}}: I. W. Forster (1971) Effect of clipping queen honey bees’ wings, New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research, 14:535-537.

{{20}}: This is fractionally less than 1% of the length of the results and discussion of my most recent paper. I need to be more succinct.

{{21}}: It’s a single author paper, but others are acknowledged. These days authorship is rightly more inclusive.

{{22}}: et no-one else at all.

{{23}}: I’m colourblind, so the colour has no bearing on the year. It just happens to be a colour I can easily see … and/or was the only working Posca pen in my bag.

{{24}}: Yellow etc etc.. The blue pen has stopped working.

{{25}}: For those following very closely it’s worth noting that colony performance was not scored for superseded colonies. Well done!

{{26}}: ‘Done properly’ of course, because a misplaced snip or stab could cause all sorts of damage and the resulting queen would be quickly replaced by the colony.

{{27}}: And probably better than average … though it doesn’t feel like that as I watch them disappear over the hedge.

{{28}}: And let’s not get into a topical Roe vs. Wade argument about squidging queen cells, or forking out drone brood.

Join the discussion ...