In praise of the 1lb round

If you go to any of the big supermarkets you will find shelf after shelf of honey for sale.

There are two things that I used to find surprising about this sort of honey.

It’s usually cheap. For example, Aldi’s Everyday Essentials honey is 99p for 340g, Lidl’s Highgate Fayre clear honey is £1.15 for 454g and Sainsbury’s Clear honey is £1.25 for 340g.

I suspect that none of this honey is produced in the UK, though they might be packaged here – an important distinction. All will have the weasel words ‘Produce of EU and non-EU countries’ in very small letters on the label.

Absolutely anywhere

Anyone with even a passing understanding of geography will appreciate that these words mean the honey comes from absolutely anywhere.

Which probably means China.

China is the biggest global honey exporter by metric tonne. The EU imports 200,000 tonnes of honey per year, 40% of which comes from China … hence ‘Produce of EU and non-EU countries’.

I’m sure these honeys are actually honey {{1}} but I’d be surprised if it is particularly good honey.

I’m sure it tastes sweet.

But that’s about it.

A triumph of style over substance

The other thing that used to surprise me about supermarket honey was the appearance.

It’s usually reasonably nicely packaged and labelled. The jar contents look uniform and doesn’t change appreciably over time. Foe example, if you leave a jar it at the back of the cupboard for 6 months it will usually look exactly the same when you rediscover it.

It will also look exactly the same if you return to buy a second jar.

It’s made like that.

During processing it has been prepared to remain attractive and unchanged just in case it doesn’t sell in the first few days or weeks of going onto the supermarket shelf.

Jar after jar looks exactly the same and will remain doing so for a long time.

This in itself isn’t an issue until you realise that the processing and packaging of the honey has probably involved all sorts of filtering and/or heating {{2}}. This is done to achieve consistency in appearance and to retain this appearance on the shelf.

For comparison … the current wholesale bulk price for UK-produced floral honey is over £3 a pound, and heather honey is more than £4. That’s 3-4 times more than the supermarket honeys listed above before jarring, labelling, transporting and markup.

First impressions last

If you sell honey it’s worth remembering that some potential customers will have only seen these cheap inexpensive offerings from the supermarkets.

That is the competition. That’s the standard against which your honey will probably be judged.

Madness of course as honey is meant for eating and it should be judged primarily, if not exclusively, on flavour {{3}}.

So what are these potential customers judging?

Appearance and (usually) price.

Or price and then appearance {{4}}.

A wildly high (or low {{5}}) price or an unappealing appearance will kill the potential sale.

If the label is unattractive, the jar is ugly, the lid is dented, the honey unevenly crystallised or frosting badly, or – horror – there are legs or antennae visible in suspension … they’ll reach for a jar on a different shelf.

Taste tests

If you sell ‘from the gate’ you can offer samples for a taste test. This is usually enough to secure a sale, even if the appearance is sub-optimal or the price unrealistic.

However, if you are selling via a third party you don’t have this luxury (but you do save a lot of time having interesting conversations about the declining numbers of bees {{6}}, different honey types, whether the honey is raw, bumble bees, hay fever, the weather etc.).

You have control over the appearance of the honey but perhaps only limited control over the price (because of the seller’s markup). The appearance must be good and the price needs to be realistic {{7}}.

Price

The price you charge for your honey is influenced by a swathe of different factors:

- type and preparation – heather, mono floral, clear, soft set

- cost of materials – foundation, frames, jars, labels, miticides

- how you value your time used when preparing the honey (and don’t forget the 7-day inspections, the swarm control, the heavy lifting, the petrol, the colonies lost to disease or failed queen mating … and perhaps even all those jars given away to family and friends!)

- level of local competition

- affluence of customers

- etc.

Just remember those bulk prices I quoted earlier.

By the time you’ve added the price of the jar and lid, the label, and the time spent bottling and delivering it, the wholesale price for a good-looking jar of high-quality local artisan-produced honey should be substantially higher.

I’ll say that again for emphasis … substantially.

Locally produced honey should be a quality product and should sell at a premium price.

Over the last decade there appears to have been a switch by many beekeepers from 1 lb (454 g) jars to 12 oz (340 g) jars. The acceptability of the price ‘on the shelf’ will be one factor that has influenced this. What was £5 a pound in 2009 is rapidly nudging towards a tenner. This may be too steep for some customers.

But the 1 lb jar still has lots going for it.

Labels and contents

There are three things that influence the appearance of a jar of honey.

- the contents

- the labelling

- the jar

As the producer you have full control over these things.

If you are selling honey you presumably have a fair idea of what the honey should look like. Soft set (creamed) honey should be smooth and uniform, a consistent colour and with little or no evidence of frosting on the inside of the jar. Clear honey should be clear, ‘sparkly‘, with no specks of wax, bee wings or mouse droppings visible {{8}}.

The label design involves an interesting mix of regulations and creativity. There are a whole lot of rules to follow on the words, weights and traceability that must be included.

After that you can use your artistic skills.

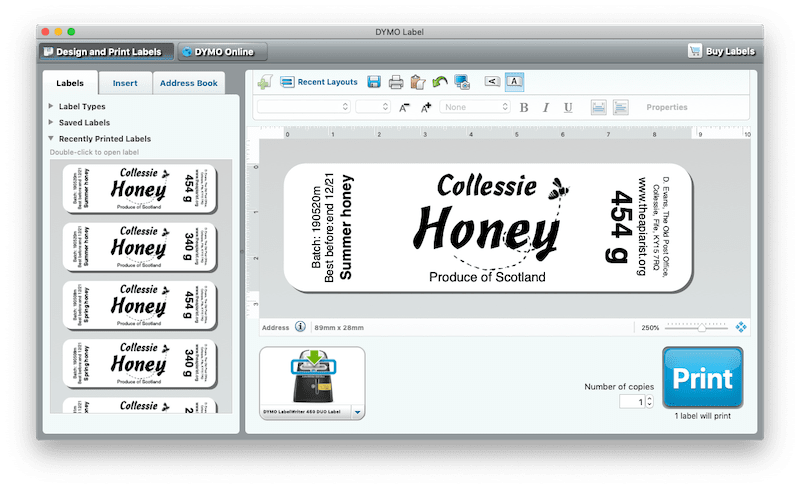

Dymo LabelWriter design and printing

My labels are a minimalist. They are simple black on white home-printed labels that don’t obscure too much of the jar. I want the customer to see the honey. They are inexpensive to produce, straightforward to apply, easy-peel, non-smearing and can be printed in batches of one to one thousand.

Which, finally, brings me to the jar itself …

Rounds, hexes and squares

Artisan honey?

A premium product should be presented in good quality packaging.

This probably isn’t a squeezy bear.

Just sayin’ 😉

You don’t have to sell honey by any particular set weight. You can package your honey in glass jars, plastic jars, snap-lid polythene containers, Kilner jars, squeezy bears etc.

But glass jars are probably both the most environmentally friendly and what most customers expect a high-quality honey to be packaged in.

So much so that if you asked someone what a honey jar looks like they will almost always describe one of two jar types.

The classic ‘1 lb round’ or a 12 oz hexagonal jar.

- 12 oz hex jar

- 1 lb round jar

Jars are not inexpensive. If you pay normal retail prices (excluding carriage) then 1 lb rounds cost ~34p each and 12 oz hex’s cost ~40p. These prices include lids {{9}}.

Honey in these types of jars won’t surprise anyone and will not put any potential customers off. They expect honey to be jarred like that.

But they also won’t stand out on the shelves from all the other jars that are the same size and shape.

For this reason I use square jars. These are easy to label, distinctive, stack and pack well together, provide a good view of the contents and are only marginally more expensive at ~43p for 12 oz.

I’ve not found a source for reasonably priced 1 lb square jars. If you have, please tell me.

Bottling it

Which in a roundabout way brings me to the subject in the title of this post.

Jarring honey, at least at the small scale I do it in, is a time-consuming manual activity. It’s an important part of the entire process as it’s what ensures that the good-looking contents appear at their best in a nice-looking container.

Aside from the label, the contents and the jar size/shape, the final appearance also depends upon these things being put together properly. The label should be centred and straight, not wonky. The honey should be in the jar, not smeared on the inside of the lid and across the screw thread.

The honey should not be full of bubbles (hint, use a honey bucket tipper and you can maximise the honey jarred from a single bucket) and, ideally, there should no bubbles trapped at the ‘shoulder’ of the jar.

Hex jars are often difficult to fill without trapping bubbles at the shoulder. Some jar styles are better than others, it all depends on how the transition from the vertical side to the neck of the jar slopes (compare the jar on the right with the one shown above).

Square jars are easy to fill. This is because there are only four corners and there is a good slope between the face of the jar and the neck, so bubbles are not trapped.

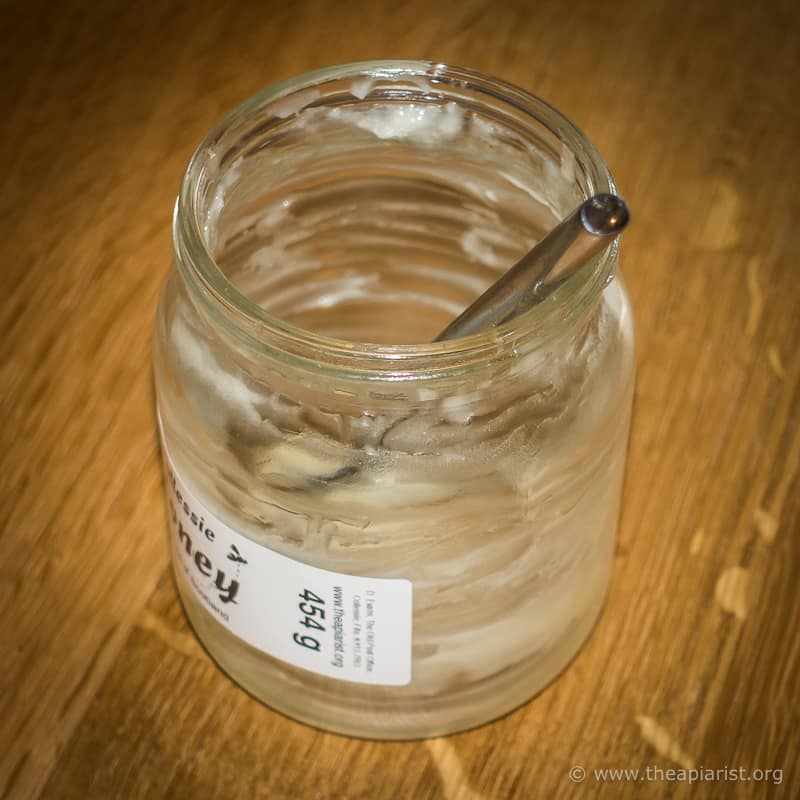

And 1 lb rounds are the best of all 🙂

There’s almost no chance of trapping bubbles at the shoulder of the jar because of the gentle curve to the bottle neck. In addition, filling the jar with 1 lb (454 g) of honey leaves almost no visible space above the honey surface once the jar lid is fitted.

The jar looks full {{10}}. Compare the picture below with the square or hex jars above.

Where jarring is concerned the 1 lb round has an additional advantage. For each large bucket of honey you have fewer jars to fill and label.

Result 😉

Unbottling it

I sell over 90% of my honey in square jars. However, almost all of the honey for family and home consumption is jarred in 1 lb rounds.

For two reasons most of the latter is soft set honey; a) the majority of customers want clear honey and b) I prefer it.

And this is where the 1 lb round really excels …

… there are no corners 🙂

With a little perseverance and a suitably sized teaspoon you can get almost all of the honey out of the jar.

Easy to fill and easy to empty. What’s not to like?

{{1}}: As opposed to some sort of processed sugar syrup. These are reputable supermarkets and they will (or should) check their suppliers carefully. Other places are less reputable and there is a huge global market in fake honey … including fake manuka honey. New Zealand produces 1700 tonnes of manuka honey per year whereas over 10,000 tonnes of manuka are sold on the global market annually. Puzzling!

{{2}}: Fine filters or diatomaceous earth remove most particulates – like pollen – which act as nuclei for granulation and only heated honey flows through these fine filters.

{{3}}: The ‘blind tasting’ category winner at annual honey shows is often rather special.

{{4}}: Only about a third of email enquiries about honey result in sales suggesting that price is the primary determinant for many potential customers.

{{5}}: Why is this so cheap? I’m here to buy a quality artisan-produced jar of local honey … £4 a pound seems very low. What’s wrong with it? Is it out of date? Is it imported and just labelled as ‘local’?

{{6}}: They’re not … since honey bees are managed any reduction in numbers must reflect a reduction in the number of beekeepers … all we need are more beekeepers.

{{7}}: This applies whether selling via a third party or from the door. Realistic does not mean rock-bottom

{{8}}: Or for that matter present.

{{9}}: These prices are calculated using the current list prices from C Wynn Jones.

{{10}}: All the jars are filled correctly with the stated weight of honey. It’s psychological.

Join the discussion ...