Growing old (dis)gracefully

… but in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.

So wrote Benjamin Franklin in 1789 {{1}}.

Taxes are a subject that I’ve not previously covered. Furthermore, I have no intention of writing about them in the future. My once a year late-night wrestle with the HMRC website is a distressing enough experience and one I’d prefer not to be reminded about.

So this week I’ll deal with that other certainty … death.

Sooner or later it will happen to us all.

No ifs or buts, and – unlike taxes – it really is a certainty.

What’s interesting about death is the ‘sooner or later’ element.

Some die young, due to bad luck, poor health or overindulgence.

Others live to a ripe old age, outliving their peers by many years or even decades.

Talking the talk

Beekeeping has been a relatively solitary pastime for the last 16 months. The restrictions imposed by lockdowns and social distancing have meant that beekeeping meetings have all been ‘virtual’.

I’ve written about these recently and it seems likely that many associations are going to continue (at least some of the time) with Zoom talks.

Whether in person, or online, one of the things that’s noticeable is that all beekeeping audiences are – how can I put this delicately? – not as young as they used to be.

By which I mean the individual beekeepers are not callow youths, but are instead older, wiser, and – of course – better looking.

In my experience, giving talks over the last decade or so, beekeeping audiences have always had an older average age than a cross-section of society.

In addition, as I briefly mentioned recently, the average age of beefarmers in the UK is about 66 years old.

Why is this?

It seems there are two possibilities:

- Since beekeeping takes a reasonable amount of time, it’s largely people who have more spare time who start or stick with the hobby. At least at the start, beekeeping also costs quite a bit of money. Again, those who are a bit older probably have more disposable income (or fewer distractions like mortgages or kids to spend it on).

- Beekeepers live longer. The relatively high average age of a beekeeping audience – when compared with a similarly-sized cross-section of society – reflects their increased longevity.

Of course, both of those are rather simplistic explanations, but it’s a start.

Do beekeepers live longer?

When you start beekeeping you tend to be interested in honey and swarm control and pathogens.

Or just honey 😉

But after a few years of successful beekeeping you probably produce quite a bit of honey. Your success in honey production is partly due to your understanding and implementation of swarm control, and by your interventions that minimise disease.

And so your interests in beekeeping expand.

Some produce award-winning candles or wax flowers, some rear hundreds of queens a season, some explore esoteric hive designs, and some become interested in the history of beekeeping.

And one of the things that’s noticeable about the history of beekeeping is that several well known beekeepers lived to a remarkably old age.

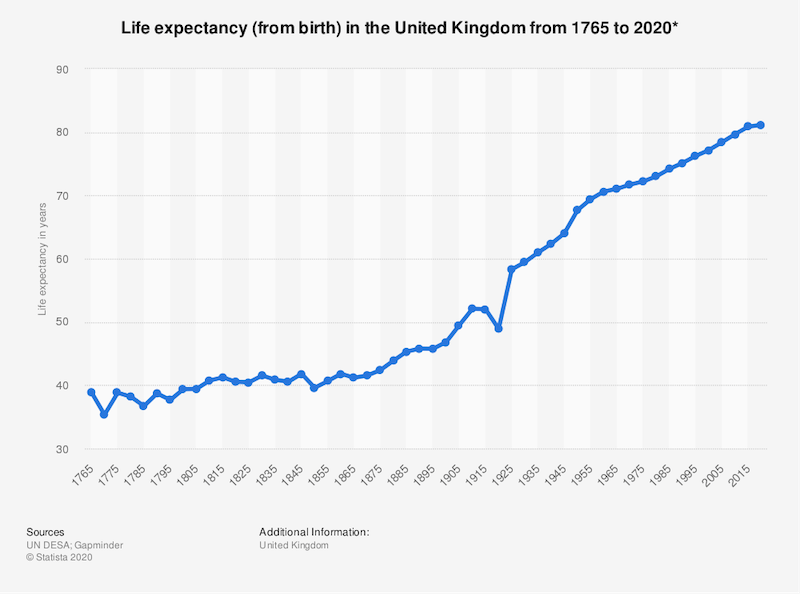

With improvements in nutrition and healthcare, the average life expectancy of the population has been increasing for the last 150 years or so.

If you were born in the 18th Century you’d be expected to live (on average) about 40 years. However, in the last third of the 19th Century, life expectancy started to increase.

I was going to say ‘inexorably increase’ were it not for that little blip around 1918-1920. That wasn’t the First World War. It was the last significant global viral pandemic, the so-called Spanish ‘flu {{2}}. Only recently has this increase in life expectancy started to plateau, and actually reverse.

Well known historical (old) beekeepers

My knowledge of the history of beekeeping is rather patchy so I did a quick search for ‘famous beekeepers‘.

Don’t bother with the first couple of hits {{3}}, but the third is the ever-dependable and enjoyable Bad Beekeeping Blog by Ron Miksha.

Here’s a few picked at anything-but-random ( 😉 ) to support my hypothesis that beekeepers live longer.

In no particular order:

- François Huber (1750-1831, 81 years), Swiss, ~40 years {{4}}. Huber was an extraordinary individual {{5}}. Despite being blind his ‘observations’ worked out many details of the life cycle of the queen and he developed one of the first observation hives.

- Lorenzo Langstroth (1810-1895, 85 years), US, ~40 years. Langstroth combined an understanding of ‘bee space’ with the movable frame ‘leaf hive’ (developed by Huber) to develop and patent the first removable frame hive.

- Brother Adam (1898-1996, 98 years), German (lived in UK), ~47 years. Brother Adam (Karl Kehrle) was an authority on bee breeding and the developer of the Buckfast strain of honey bees. He resigned his post of beekeeper at Buckfast Abbey at the age of 93.

- Charles Dadant (1817-1902, 85 years), French (lived in US), ~40 years. Dadant invented the Dadant hive, ran thousands of hives (after failing as a vintner) and founded the – still flourishing – Dadant & Sons beekeeping business.

- Eva Crane (1912-2007, 95 years), UK, ~52 years. Eva Crane was a mathematician/physicist who spent much of her (long) life doing research on bees. She founded the Bee Research Association (still flourishing as the International Bee Research Association) and wrote hundreds of papers, and notable books, on bees and beekeeping.

- Harry Laidlaw (1907-2003, 96 years), US, ~51 years. Harry Laidlaw was one of the pioneers of studies on bee genetics and optimised methods for instrumental insemination of queens.

- Karl von Frisch (1886-1982, 96 years), German, ~39 years. Karl von Frisch deciphered the waggle dance of honey bees and received the Nobel Prize in 1973.

And there are many others … including many much less famous but equally old {{6}}.

Correlation not causation

Just because (some) beekeepers live a long time doesn’t mean that beekeeping is responsible for their longevity.

Perhaps they’ve just got ‘good genes’ and they’d have lived into their 80’s or 90’s whether they’d been beekeepers or BASE jumpers.

Maybe it takes that long to become an acknowledged expert at beekeeping?

How many famous beekeepers can you name who died young?

If Harry Laidlaw had only lived to his mid-60’s (still older than the average for his year of birth) perhaps he’d have been unknown?

Unlikely … he published his first book at the age of 25, was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science at 48 and was the first Associate Dean for Research in UC Davis in his late 50’s.

All of the individuals listed enjoyed a near-lifelong association with bees and were clearly exceptional beekeepers well before they also achieved an exceptional age (considering the year that they were born).

So perhaps there is something about bees or beekeeping that makes beekeepers live longer?

One possibility is that honey is good for you.

Although some beekeepers don’t like honey {{7}}, most undoubtedly do. Honey has a host of antimicrobial, antiviral, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, as well as being a guaranteed ( 😉 ) way to prevent hay fever.

Or perhaps it’s bee stings? {{8}}

Caveat

Treat most of what I’ve written above with some caution.

My selection of famous (old) beekeepers is extremely selective.

The reason audiences in beekeeping association meetings have a high average age is almost certainly due to spare time and disposable incomes … and because all the young ones are out partying.

It’s not my sort of science, but a proper study of the association between longevity and beekeeping would be quite interesting.

Do beekeepers actually live longer than non beekeepers?

Is there a causative association? Is it associated with beekeeping per se, or do non-beekeepers who eat honey also live longer? How many hive/years do you need to keep bees to increase your longevity? If it’s bee stings that are beneficial, do beekeepers who keep stingless bees also live long and healthy lives?

There is literally a certain finality about studying the age at death. Are there perhaps other markers of longevity that could be investigated a little earlier in a beekeeper’s life?

There certainly are …

Chromosomes and DNA replication

We (beekeepers) have 23 pairs of chromosomes {{9}} that consist of DNA and proteins and contain the majority of our genetic material {{10}}.

The chromosomes are in nucleus of the cell.

Cells associate to form tissue (like muscle or nerves) which associate to form organs (like the heart or brain).

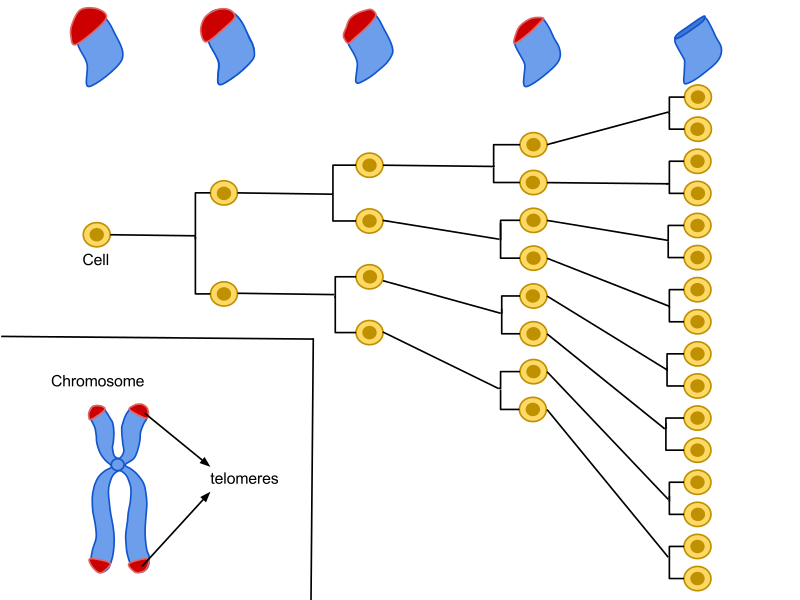

As humans grow – from egg, to embryo, to foetus, to adult – these cells have to divide. And the chromosomes have to be duplicated to ensure that all cells end up with the required 23 pairs.

Chromosomes are not circular but are essentially linear strands of DNA. This introduces a problem.

The enzymes that copy and make new DNA (the DNA polymerase) only ‘work’ in one direction. Since DNA consists of two antiparallel strands this means that the polymerase copies one strand directly to make one continuous product, but it copies the other strand in small pieces, and then joins them together.

The details really don’t matter … but the consequences do.

The small piece synthesised at the very end of the discontinuously copied strand isn’t quite at the very end of the strand {{11}}.

Frankly, this is a bit of a design flaw 🙁

Telomeres

As a consequence of this discontinuous copying, one of the strands of the DNA molecule gets a little bit shorter every time it is copied.

The DNA of chromosomes contains all the genes that make all the proteins that makes all the cells that get together to form all the tissues that create the organs that make beekeepers.

Phew!

So, if the little bit of the chromosome that’s lost during replication happened to contain an essential gene, things would go very seriously wrong™.

But chromosomes have a sort of ‘get out of jail card’.

The ends of the chromosome contain a region of highly repetitive and non-coding {{12}} DNA called telomeres. You can imagine the telomere as a sort of ‘cap’ at the end of the chromosome.

During replication, little bits of this cap are lost – the cap gets shorter – but this truncation does not result in the loss of any essential genes.

And all this telomere shortening is rather predictable.

As cells divide – during growth or tissue repair – the telomeres shorten. Therefore, if you measure telomere length you can get an idea of how many division it has undergone and therefore how old it is.

Telomere length is therefore a measure of biological age.

Except it’s not quite that simple

There are a bunch of things that also influence telomere length.

For example, the age of the father influences the length of the child’s telomeres.

Telomeres also accumulate damage – and so shorten – through oxidative stress. This is a process that results from the excess production of oxidants such as peroxides, free radicals and reactive oxygen species. These are chemical intermediates in normal biochemical processes. The cell can cope with small amounts of oxidants. However, the protection mechanisms become swamped if they are in excess, resulting in cellular damage.

Some diets are rich in antioxidants which can (or at least are hypothesised to) reduce oxidative stress.

Honey can contain high levels of polyphenols, these are well known antioxidants that are also found in some fruits, vegetables and olive oil.

Finally … we’re getting somewhere 😉

There are studies that demonstrate that eating honey every day increases the levels of antioxidants {{13}}. However, I’m not aware that these or other studies were extended to investigate whether the test cohort also exhibited a reduced rate of telomere shortening.

This isn’t surprising … the inherent variation between individuals and the relatively slow rate at which telomeres shorten means thousands of individuals would need to be analysed. Potentially over many years.

But there is also a study of telomere length in beekeepers … which is the reason for the 2,200 word introduction above.

Beekeepers and telomeres

A Malaysian research team {{14}} have measured telomere length in 30 beekeepers and the same number of age-matched non-beekeepers.

The beekeepers chosen had all been keeping bees for at least five years. The non-beekeepers didn’t just not keep bees {{15}}, they also did not consume any bee products (honey, propolis {{16}} or royal jelly {{17}} ). In addition to being age-matched (average age ~42 years) both groups excluded individuals with known disease.

And I wouldn’t have been telling you all this unless the telomere length did differ significantly. The non-beekeeper’s had telomeres that were ~30% shorter.

Chronologically they were the same age, but biologically they were older.

This small study also investigated whether there was a correlation between the period of beekeeping, the number of bee products consumed, or the period or frequency of bee product consumption, and telomere length.

Telomere length only correlated with the frequency and duration of consumption of bee products, not with the types of products or the number of years of beekeeping.

The significance of these sorts of population-based studies is related to the scale of the study. This is a small study, and the only one I’m aware of that specifically investigates telomere length in beekeepers.

It has only been cited 7 times and has not been repeated.

It remains firmly in the ‘interesting observation’ rather than ‘acknowledged fact’ category.

So all those afternoons hunched over the hive appear to make no difference {{18}}, but having honey every day on your porridge might actually make you younger.

Biologically younger … you’ll still look old 😉

{{1}}: Though the ‘certainty of death and taxes’ phrase originates from the British actor Christopher Bullock in 1716.

{{2}}: The more correctly named H1N1 ‘flu killed an estimated 50 million people in 1918. That represented ~2.7% of the global population. For comparison, Covid has so far killed just under 5 million people. However, in the intervening period the global population has increased by over 5 billion, meaning that Covid has only accounted for ~0.06% of the population and won’t register on this type of graph in the future.

{{3}}: Their idea of ‘famous’ often tallies with Andy Warhol’s … and many of those chosen are famous for things other than beekeeping.

{{4}}: This figure is the average life expectancy from birth of someone born in the same country.

{{5}}: Who deserves a post entirely of his own.

{{6}}: Look at the audience in the beekeeping talks you attend this winter.

{{7}}: Do they die young?

{{8}}: In which case the hammering I received yesterday probably added a decade to my life expectancy.

{{9}}: Bees have 16 pairs, at least the queen and the workers do, the drones are haploid and only contain 16 chromosomes.

{{10}}: There’s a bit more tucked away in the mitochondria (the energy factories within the cell), but we’ll ignore that for convenience.

{{11}}: This is first year degree biochemistry level, so way above my pay grade. I’m a virologist and I sort of lump all this cellular biochemistry together into the category “stuff happens” … You should probably do the same.

{{12}}: It does not contain any genes.

{{13}}: For example, this clinical trial in which subjects ate about 100 g of honey/day and which concluded “Given that the average sweetener intake by humans is estimated to be in excess of 70 kg per year, the substitution of honey in some foods for traditional sweeteners could result in an enhanced antioxidant defense system in healthy adults”.

{{14}}: Nasir NF, Kannan TP, Sulaiman SA, Shamsuddin S, Azlina A, Stangaciu S. The relationship between telomere length and beekeeping among Malaysians. Age (Dordr). 2015;37:9797. doi:10.1007/s11357-015-9797-6

{{15}}: Poor souls …

{{16}}: Ditto.

{{17}}: They’re not missing much in this case.

{{18}}: Though they make me feel older.

Join the discussion ...