Frequently asked questions

The 2020/21 winter has been very busy with online talks to beekeeping associations. I’m averaging about five a month, with only the fortnight over Christmas and New Year being a bit quieter.

When chatting to the organisers of these talks it’s clear that they are getting increasingly successful {{1}}. Audience numbers are encouragingly high as people become more familiar with online presentations.

Beekeepers know they can lounge around in their pyjamas drinking wine, chat with their friends before and after the talk {{2}}, and listen to a beekeeping presentation … a sort of lockdown multitasking.

Some of you that spend hours each day on Zoom will know exactly what I’m talking about 😉

I still lament the absence of homemade cakes, but I suspect the online format is here to stay. At least for some associations, or at least some of the winter programme each year.

Talking to myself

There’s little point in doing science unless you tell others about it and, as as a scientist, I have presented at invited seminars and conferences for my entire career.

Some readers will be familiar with public speaking in one form or another. They’ll be familiar with the frisson of excitement that precedes stepping up to the podium in a large auditorium.

Assuming there’s a large audience filling the large auditorium of course 😉

Those with little experience of speaking might wish the audience was a bit smaller, or a lot smaller … or not there at all.

But the reality is that the audience is a really important part of a presentation. At least, they are once the speaker has sufficient confidence to calm down, to stop worrying they’ll say something stupid, and to ‘read’ the audience.

By observing the audience the speaker can determine whether they’re still interested and attentive. Not just in the topic (after all, they’re sitting there rather than disappearing to the coffee shop), but in particular parts of the presentation.

Are you going too fast?

Have you lost their attention?

Was that fancy animated slide you spent 20 minutes on a dismal failure?

Did that last witty aside work … or did it crash and burn? {{3}}

Almost none of which can be determined when delivering a Zoom-type online presentation 🙁

You can ‘see’ the audience.

Or parts of it.

Postage stamp-sized headshots, with poor lighting, distracting backgrounds {{4}} and enough pixelation to make nuanced judgements about boredom or even species sometimes tricky.

Is that a Labradoodle in the audience … or just another lockdown haircut?

Has the internet frozen … or has everyone simply fallen asleep?

It’s not ideal, but it’s the best we’ve got for now.

Which makes the question and answer sessions even more important than usual.

Mixed abilities

My talks usually include a 5 minute intermission. Talking for an hour uninterrupted is actually quite tiring {{5}} and it’s good to make a cup of tea and gather my thoughts for ’round two’.

It also allows the audience to raise questions about subjects mentioned in the first half that left them confused.

Fortunately these ‘half time’ questions tend to be reassuringly limited in number {{6}}.

However, at the end of the talk there is usually a much more extensive Q&A session. This often covers both the topic of the talk and other beekeeping issues.

A typical audience contains beekeepers with a wide range of beekeeping experience. Enthusiastic beginners {{7}} jostle for screen space with ‘been there, done that, bought the T-shirt’ types who have forgotten more than I’ll ever know.

Inevitably this means the talk might miss critical explanations for beginners and omit some of the nuanced details appreciated by the more experienced. As the poet John Lydgate said:

You can please some of the people all of the time, you can please all of the people some of the time, but you can’t please all of the people all of the time {{8}}.

Think about this simple statement:

“Varroa feed on the haemolymph of developing pupae.”

The beginner might not know what haemolymph is … or, possibly, even what Varroa is.

The intermediate beekeeper might be left wondering whether the mite also feeds on nurse bees when ‘crowdsurfing’ around the colony during the phoretic stage of the life cycle.

And the experienced beekeeper is questioning whether I know anything about the subject at all as I’ve not mentioned fat bodies and their apparently critical role in mite nourishment.

So I encourage questions … to help please a few more of the people 😉

You’re on mute!

In my experience these are best submitted via the ‘chat’ function. The host – an officer of the BKA or a technically-savvy member press ganged into hosting the talk – can then read them out to me.

Or I can … if I can find my glasses.

One or two beekeeping associations have a Zoom ‘add in’ that allows the audience to ‘upvote’ written questions, so that the most popular appear at the top of the list {{9}}. This works really well and helps ‘please more of the people more of the time’.

The alternative, of asking the audience member to unmute their mic and ask the question is somewhat less satisfactory. It’s not unusual to watch someone wordlessly ‘mouthing’ the question while the host (or I) try and explain how to turn the microphone on.

Finally, it’s worth emphasising that the Q&A session is – as far as I’m concerned – one of the most helpful and enjoyable parts of the evening.

Enjoyable, because I’m directly answering a question that was presumably asked because someone wanted or needed to know the answer {{10}}.

Helpful, because over time these will drive the evolution of the talk so that it better explains things for more of the audience.

Anyway – that was a longer introduction than I intended – what sort of questions have been asked frequently this winter (and the talks they usually appeared in).

What do you define as a strong colony? (Preparing for winter)

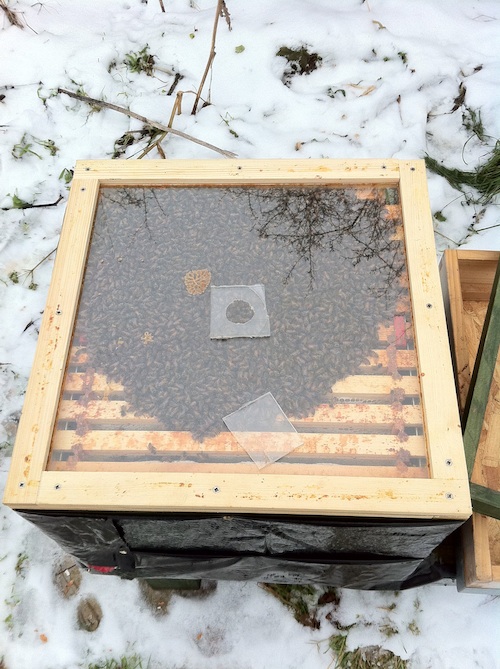

Strong colonies overwinter better than weak colonies. They contain more bees. This means that the natural attrition rate of bees during the winter shouldn’t reduce the colony size so much that it struggles to thermoregulate the cluster.

I also think large winter clusters retain better ‘contact’ with their stores, so reducing the chances of overwinter isolation starvation.

Strong colonies are also likely to be healthy colonies. Since the major cause of overwintering colony losses is Varroa and the viruses it transmits, a strong healthy colony should overwinter better than a weak unhealthy colony.

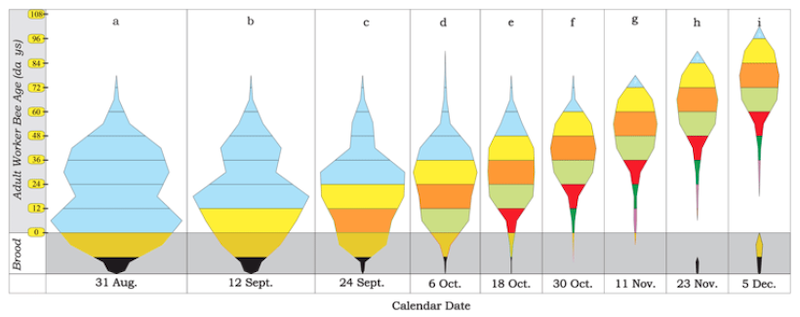

However, you cannot necessarily judge the strength of a colony in June/July as an indicator of colony strength in the late autumn and winter.

This is because the entire population of bees has turned over during that period.

A hive bulging with bees in summer might look severely depleted by November if the mite levels have not been controlled in the intervening period.

The phrase ‘a strong colony’ is also relative … and influenced by the strain of bees. Native black bees rarely need more than a single brood box. Compare them to a prolific carniolan strain and they’re likely to look ‘weak’, but if they’re filling the single brood box then they’re doing just fine.

When should I do X? (Rational Varroa control and others)

When usually means ‘what date?’

X can be anything … adding Apivar strips, uniting colonies, adding supers, dribbling oxalic acid.

This is one of the least satisfactory questions to answer but the most important beekeeping lesson to learn.

A calendar is essentially irrelevant in beekeeping.

Due to geographic/climatic differences and variation in the weather from year to year, there’s almost nothing that can be planned using a calendar.

Only three things matter, the:

- state of the colony

- local environment – an early spring, a strong nectar flow, late season forage etc.

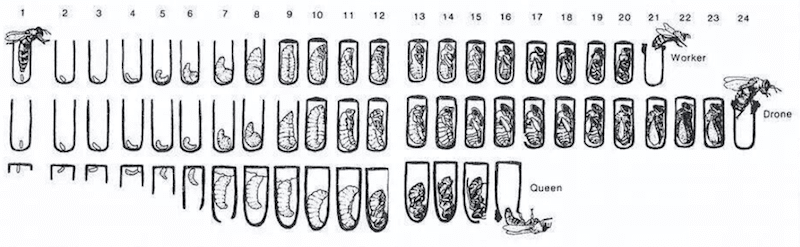

- development cycle of queens, workers and drones

By judging the first of these, with knowledge of the second and a good appreciation of the third, you can usually work out whether treatments are needed, colonies united or supers added etc.

This isn’t easy, but it’s well worth investing time and effort in.

The last of these three things is particularly important during swarm control and when trying to judge whether (or when) a colony will be broodless or not. The development cycle of bees is effectively invariant {{11}}, so understanding this allows you to make all sorts of judgements about when to do things.

For example, knowing the numbers of days a developing worker is an egg, larva and pupa allows you to determine whether the colony is building up (more eggs being laid than pupae emerging) or winding down for autumn (or due to lack of forage or a failing queen).

Likewise, understanding queen cell development means you know the day she will emerge, from which you can predict (with a little bit of weather-awareness) when she will mate and start laying.

How frequently should you monitor Varroa? (Rational Varroa control)

This question regularly occurs after discussion of problematically high Varroa loads, particularly when considering whether midseason mite treatment is needed.

Do you need to formally count the mite dropped between every visit to the apiary?

Absolutely not.

If you are the sort that does then be aware it’s taking valuable time away from your trainspotting 😉 {{12}}

The phoretic mite drop is no more than a guide to the Varroa load in the hive.

Think about the things that could influence it:

- A colony trapped in the hive by bad weather has probably got more time to groom, so resulting in an increased mite drop.

- An expanding colony has excess late stage larvae so reducing the time mites spend living phoretically.

- A shrinking colony will have fewer young bees, so forcing mites to parasitise older workers. Some of these will lost ‘in the field’ and more may be lost through grooming.

- Strong colonies could have a much lower percentage infestation, but a higher mite drop than an infested weak colony. You need to act on the latter but perhaps not the former.

- And a multitude of other things that really deserve a more complete post …

So don’t bother counting Varroa every week … or even every month.

I think checking a couple of times a season – towards the end of spring and in mid/late summer – should be sufficient. You can do this by inserting a Varroa tray for a week, by uncapping drone brood and looking for mites, or by doing an alcohol wash on a cupful of workers (but these methods aren’t comparable with each other as they measure different things with different efficiencies).

But you must also look for the damaging effects of Varroa and viruses at every inspection.

If there are significant numbers of bees with deformed wings – characteristic of high levels of deformed wing virus (DWV) – then intervention will probably be needed.

And if there are increasing numbers of afflicted bees since your last regular inspection it’s almost certain that intervention will be needed sooner rather than later.

I should add that I also count mite drop during treatment. This helps me understand the overall mite load in the colony. By reference to the late summer count I can be sure that the treatment worked.

What do you mean by a quarantine apiary? (Bait hives for profit and pleasure)

This question has popped up a few times when I discuss moving an occupied bait hive and checking the health of the colony.

A swarm that moves into a bait hive brings lots of things with it …

Up to 40% by weight is honey which is very welcome as they will use it to draw new comb. If there’s good forage available as well it’s unlikely the swarm will need additional feeding.

However, the swarm also brings with it ~35% of the mites that were present in the colony that swarmed. These are less welcome.

I always treat swarms with oxalic acid to give them the best possible start in their new home.

More worrisome is the potential presence of either American or European foul broods. Both can be spread with swarms. The last things you want is to introduce these brood diseases into your main apiary.

For this reason it is important to isolate swarms of unknown provenance. The logical way to do this is to re-site the occupied bait hive to a quarantine apiary some distance away from other bees. Leave it there for 1-2 brood cycles and observe the health and quality of the bees.

What is ‘some distance?’

Ideally further than bees routinely forage, drift or rob. Realistically this is unlikely to be achievable in many parts of the country. However, even a few hundred yards away is better than sharing the same hive stand.

If you keep bees in areas where foul broods are prevalent then I would argue that this type of precautionary measure is essential … or that the risk of collecting swarms is too great.

And how do you know if foul broods are prevalent in your area?

Register with the National Bee Unit’s Beebase. If there is an outbreak near your apiary a bee inspector will contact you.

Remember also that the presence of foul broods in an area may mean that the movement of colonies is prohibited.

‘Asking for a friend’ type questions

These are great.

These are the sort of questions that all beekeepers are likely to need to ask at sometime in their beekeeping ‘career’.

Typically they take the form of two parts:

- a description of a gross beekeeping error

- an attempt to make it clear that the error was by someone (anyone) other than the person asking the question 😉

Here are a couple of more or less typical ones {{13}}.

- My friend (who isn’t here tonight) forgot to remove the queen excluder and three full supers from their colony in August. Should I, oops, she remove them now?

- Here’s an an entirely hypothetical scenario … what would you recommend treating a colony with in March if the autumn and midwinter mite treatments were overlooked?

- Should my friend remove the Apiguard trays he a) added in November, or b) placed in his colonies before taking them to the heather?

- I’d been advised by an expert beekeeper to squish every queen cell a few days after discovering my colony had swarmed in June. It’s now late September … how much longer should I wait for the colony to be queenright?

These are very good questions because they illustrate the sorts of mistakes that many beginners, and some more experienced beekeepers, make.

There’s absolutely nothing wrong with making mistakes. The problem comes if you don’t learn from them.

I’ve made some cataclysmically stupid beekeeping errors.

I still do … though fewer now than a decade ago, largely because I’ve managed to learn from some of them.

Partly I learned from thinking things through and partly from asking someone else … “A friend has asked me why his colony died. Was it the piezoelectric vibrations from the mite ‘zapper’ bought from eBay or was the hive he bought not suitable?“

{{1}}: Not mine, but the format generally.

{{2}}: And sometimes during …

{{3}}: Like the last three?

{{4}}: Though gratifyingly few attempts at Bookcase Credibility.

{{5}}: Though not in a ‘working a 12 hour shift in ITU’ or ‘running a marathon’ sense of the word tiring.

{{6}}: Suggesting I’m largely making sense … or that I’ve said “I’ll cover this later” sufficiently frequently to head off inevitable questions.

{{7}}: Some of whom may have yet to get their first bees.

{{8}}: They didn’t really speak like this in the 15th Century, so this is a version of the quote popularised by Lincoln.

{{9}}: It’s the Q&A webinar function I think.

{{10}}: There are other sorts of questions that I’m very familiar with from scientific conferences … like the ‘look how much I know’ question, or the ‘my lab did did that 5 years ago, why are you wasting your time?’ question. Obviously, I’m familiar with these as a speaker, not as the the one posing the question …

{{11}}: Temperature can influence things very slightly.

{{12}}: With apologies to any beekeeping trainspotters, or trainspotting beekeepers.

{{13}}: Names, characters, businesses, places, events, locales, and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental.

Join the discussion ...