Fainting goats ... and queens

Myotonia congenita is a genetic disorder that affects the muscles used for movement. Myotonia refers to the delayed relaxation of these skeletal muscles, resulting in a variety of obvious symptoms including temporary paralysis, stiffness or transient weakness.

In humans these symptoms are often manifest as difficulty in swallowing, gagging and frequent falls. Children are affected more than adults. One of the most dramatic manifestations are the falls (‘fainting’) that can occur as a result of a hasty movement.

Although physiologically distinct, ‘fainting’ is a reasonably accurate description of the sudden loss of movement and the transient nature of the disorder. Like fainting, loss of movement is usually quickly resolved. However, unlike fainting, myotonia congenita involves muscular rigidity or stiffness, so more closely resembles catalepsy.

Genes

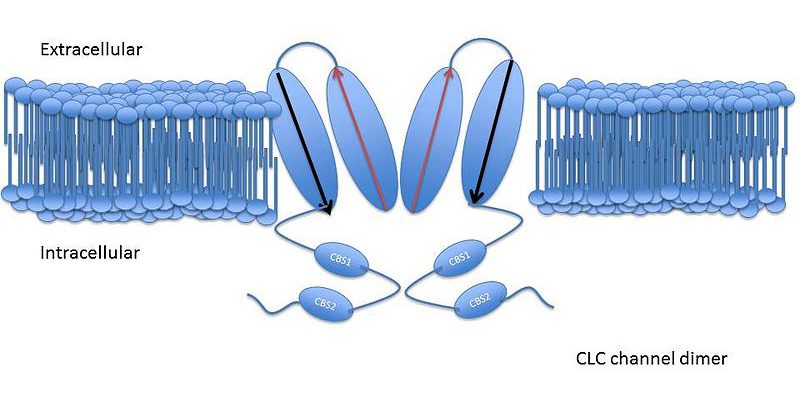

There are two types of myotonia congenita, termed Thomsen disease and Becker disease, both of which are usually associated with mutations in the gene CLCN1 {{1}}. This encodes a chloride channel (a ‘hole’ through the cell membrane that allows the transfer of chloride ions) critical for muscle fibre activity.

With loss-of-function mutations in CLNC1 the muscle fibre continues to to be activated. When stimulated, for example if the fibre is triggered to suddenly contract for jumping or running (or to stop a fall), the muscle fibre is hyper-excitable and continues to contract, and shows delayed relaxation.

Around 1 in 100,000 people exhibit myotonia congenita, though it is about ten times more common in northern Scandinavia. Treatment involves use of a number of anticonvulsant drugs.

The same loss-of-function CLCN1 mutation in humans is seen in symptomatically similar horses, dogs … and goats.

Goats

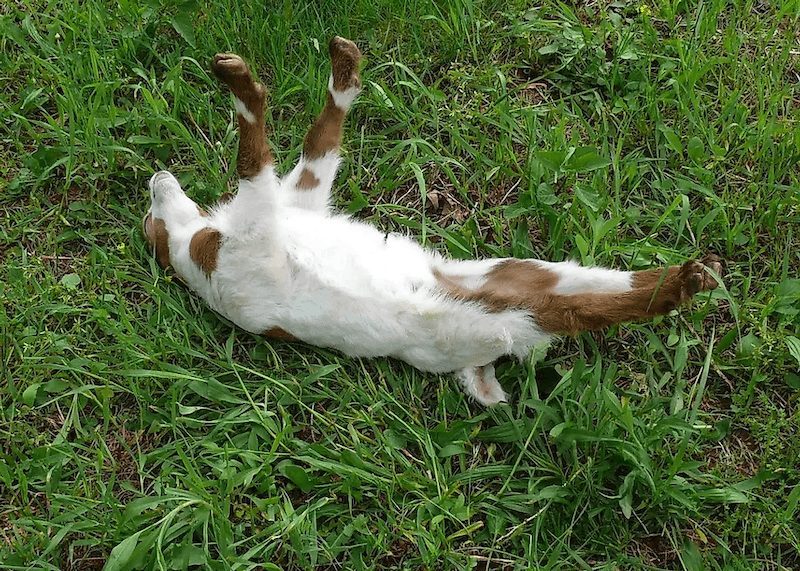

In the late 19th century four goats were imported to Marshall County, Tennessee. Their strange behaviour when startled was first described in 1904 and defined as a congenital myotonia by Brown and Harvey in 1939.

These pre-war studies formed the basis of of our understanding of both the physiology and genetics of myotonia congenita, though the specific mutation in the CLCN1 gene was only confirmed several years after it had been identified in humans.

Since then myotonic goats have become an internet staple, with any number of slightly distressing (for me at least, if not for the goats) YouTube videos showing their characteristic fainting when surprised or frightened {{2}}.

Don’t bother watching them.

If you want to see a fainting goat in action watch little ‘Ricky’ jump up onto a swinging seat on the National Geographic website.

It’s a perfect example.

He jumps up, gets a mild fright as the swing moves, goes stiff legged and simply rolls over and falls to the ground. A few moments later he’s back on his feet again, looking slightly shaken perhaps, but none the worse for wear.

Queens

All of that preamble was to introduce the topic of fainting queens.

This was a subject I’d heard about, but had no experience of until last week.

Periodically it gets discussed on Beesource or the Beekeepingforum – usually the topic is raised by a relatively small-time amateur beekeeper (like me) and it gets a little airtime before someone like Michael Palmer, Michael Bush, Hivemaker or Into the Lion’s Den {{3}} shuts down the conversation with a polite “Yes, I see it a few times a year. They recover”, or words to that effect.

Since these commercial guys handle hundreds or perhaps thousands of queens a year I think we can safely assume it’s a relatively rare phenomenon.

Since I don’t handle hundreds or thousands of queens a year – and you probably don’t either – I thought the incident was worth recounting, so you know what to expect should it ever happen.

And to do that I have to first explain the fun I had with the first of the two queens in the hive I was inspecting.

A two queen colony

It was late afternoon and I was inspecting the last of our research colonies in the bee shed.

The hive had two brood boxes and a couple of supers. Nothing particularly surprising in that setup at this time of the season; the colony was quite strong, the spring honey had been extracted and a couple of supers had been returned to the hive for cleaning.

However, it wasn’t quite that straightforward.

The lower brood box had been requeened ~3 weeks earlier with a mature queen cell from one of my queen rearing attempts. I’d seen that the virgin had emerged and restricted her to the lower box at my last visit.

I’d added a queen excluder (QE) over the lower box with the intention of removing all the old frames above the QE once the brood had emerged.

However, at that last visit I’d ended up with a good looking {{4}} ‘spare’ virgin queen. Although I had no need for her at the time, and no time to make up a nuc {{5}}, I decided to put her in a fondant-plugged introduction cage in this upper box.

This ‘upper’ queen couldn’t fly and mate in the week I was away, but I reasoned that I could merge the colony with the bottom box if the ‘lower’ queen failed to mate {{6}}.

So, after adding the virgin queen to the top box I added a second QE and the two supers.

She can fly …

Having removed the supers and the upper QE I carefully inspected the upper box looking for the virgin queen who had been released from the cage

No sign of her 🙁

I went through the box again.

Time to try some of the ‘queen finding tricks’.

I moved three frames out of the way having examined them very carefully. The remaining 8 frames were then spaced out as four, well separated, pairs. I let the colony settle for a few minutes and then looked at the inner face of each pair of frames.

No sign of her 🙁

I looked again … nada, rien, niets, nunda, dim byd and sod it {{7}}.

The obvious conclusion was that the colony had killed the queen after releasing her from cage.

How uncharitable.

I reassembled the upper brood box and lifted it off the lower QE, in preparation to leave it outside the shed door while I went through the lower box.

As I carried the brood box to the door I briefly looked up and saw a {{8}} virgin queen climbing up the inner pane of one of the shed windows, flapping frantically and fast approaching the opening that would allow her escape.

For obvious reasons I have no photographs of the next few minutes.

For those unfamiliar with the bee shed windows, these have overlapping outer and inner panes, so are always open. They provide a very effective ‘no moving parts’ solution to clearing the shed of bees very quickly.

Which was the very last thing I wanted at that moment 😉

… rather well

I had a brood box and hive tool in my hands, the shed door was wide open, there was all sorts of stuff littering the floor and the virgin queen was inches away from making a clean getaway.

It’s worth noting that when virgin queens are disturbed and fly they almost always return to the hive. However, the hives in the shed have a single entrance and all the hives were already occupied with queens. I couldn’t let her fly and hope for the best … it probably wouldn’t end well.

By balancing half the brood box on an unoccupied corner of an adjacent hive roof I made a largely ineffective swipe for the queen, but disturbed her enough she flew away from the window in spirals around my head.

I s t r e t c h e d to reach the shed door and pulled it close, so reducing the possible exits from eight to seven. A small victory.

I put the brood box safely on the floor, leaning at an angle against the hive stand {{9}}, and abandoned the hive tool.

The next 5 minutes were spent ineptly trying to catch the queen. When she wasn’t flying around the shed (where the lighting isn’t the best) she usually made for the same window.

The one behind the hive with four supers stacked on top 🙁

After a few more laps of the shed, dancing around the precariously balanced brood box and reaching around the hive tower for the window, I finally caught her.

And caged her {{10}}.

I’m looking for publisher for my latest book, ‘Slapstick beekeeping’. If any readers know of a publisher please ask them to contact me.

After all that I should have had a little rest. I’d had enough excitement for the afternoon {{11}}.

But there was still the queen in the bottom box to find and mark.

Feeling faint

The queen in the bottom box was mated and laying well.

I made a near-textbook example of finding her {{12}}.

After moving aside a few frames I should have announced (to the non-existent audience), “She’s on the other side of the next frame … ” (the big reveal) ” … ah ha! There you are my beauty!”.

Holding the frame in one hand I checked my pockets for my marking cage {{13}}.

All present and correct.

I then calmly picked her up by her wings. She was walking towards me, bending slightly as she crossed over another bee, so her wings were pushed up and away from her abdomen.

A perfect ‘handle’.

I didn’t touch her abdomen, thorax or head.

And, as soon as I lifted her from the frame, she fell into a swoon and ‘dropped dead’.

Her wings were extended to the sides, her abdomen was curled round in a foetal position and she appeared completely motionless.

I dropped her into the marking cage and took the photo further up the page.

It was 6:49 pm.

For several minutes there was no obvious movement at all. Her legs and antennae were immobile. She showed no sign of breathing.

I gently shook her out onto a small piece of Correx on a nuc roof to watch and photograph her. I picked her up by the wing and held her in my palm … perhaps she needed some warmth to ‘come round’.

Was that a twitch?

Or was that me shaking slightly because I’d inadvertently killed her?

Several more minutes of complete catatonia {{14}} passed … and then a gentle abdominal pulsing started.

This was now 10-11 minutes after I’d first picked her up.

Which got a bit stronger and was accompanied by a feeble waggle of the antennae.

And was followed a minute or so later by a bit of uncoordinated leg flexing.

And after 15 minutes she took her first steps.

It looked like she’d been on an ‘all nighter’ and was still rather the worse for wear.

I slipped her into a JzBz queen cage, sealed it with a plastic cap, and left it hanging between a couple of brood frames.

From picking her up to placing the caged queen into the brood box had taken 24 minutes.

I reasoned that if …

- she fully recovered they’d feed her through the cage and I could release her the following morning

- I’d released her immediately and she’d acted abnormally the colony might have killed her off

- she did not recover I would at least be able to find the corpse easily ( 🙁 ) and so could confidently requeen the colony (with the virgin I’d tucked away safely in my pocket)

The following morning the cage was covered in bees and she looked just fine, so I released her.

She walked straight down between the frames as though nothing untoward had happened.

I didn’t have the heart to mark and clip her … I didn’t want to risk her ‘fainting’ again and, if she had, didn’t have the time to hang around while she recovered {{15}}.

So was this ‘fainting’ myotonia congenita?

I suspect not.

Another name for the Tennessee fainting goat is the ‘stiff-legged’ goat. This reflects the characteristic rigidity in the limbs when the muscles fail to relax. The queen’s legs were curled under her, rather than being splayed out rigidly.

However, this interpretation may simply reflect my near complete ignorance of the musculature of honey bees 😉

However, I do know that the basics of muscle contraction and relaxation are essentially the same in invertebrate and vertebrate skeletal muscle. There are differences in the innervation of muscle fibres, but the fundamental role of chloride channels in allowing muscle relaxation is similar.

Therefore, for this fainting queen to be affected by myotonia congenita she should have a mutation in the CLCN1 gene encoding the chloride channel.

Although the honey bee genome has been sequenced a direct homolog for CLCN1 appears not to have been identified, though there are plenty of other chloride channels present {{16}}.

The majority of the 60 or so mapped mutations associated with myotonia congenita (in humans) are recessive. Two copies of the mutated gene (in diploids, like humans or female honey bees) are needed for the phenotype to occur.

Of course, drones are haploid so it should be easier to detect the phenotype.

I’ve never heard of drones ‘fainting’ when beekeepers practise their queen marking skills on them. Have you?

Repeated fainting

I’ll try to mark and clip this queen again.

It will be interesting to see if she behaves in the same way {{17}}.

A quick scour of the literature (or what passes for the ‘literature’ on weird beekeeping phenomena i.e. the discussion fora) failed to turn up examples of the same queen repeatedly fainting.

Or any mention of daughter queens showing the same behaviour.

All of which circumstantially argues against this being myotonia congenita.

However, there are many other causes of sudden fainting (from the NHS website):

- standing up too quickly – (low blood pressure)

- not eating or drinking enough

- being too hot

- being very upset, angry, or in severe pain

- heart problems

- taking drugs or drinking too much alcohol

… though I can exclude the last one as my bees are teetotal 😉

So, there you have it, a brief account of a cataleptic queen … and her recovery.

Notes

A fortnight after the events described above I clipped and marked the queen. I did everything the same – picked her up by the wings in the shed (so again not exposed to bright sunlight – which may be relevant, see the comment by Ann Chilcott).

She (the queen) didn’t faint. She behaved just like the remaining 4 queens I marked on the same afternoon.

So no repeat of the ‘amateur dramatics’ 🙂

{{1}}: There are rarer forms associated with the mutation of a voltage gated sodium channel (also involved in muscle relaxation), though symptomatically these are similar.

{{2}}: These usually seem to involve giggling youths chasing the goats around and deliberately scaring them … not my idea of entertainment.

{{3}}: All large (in the ‘number of hives’ sense) commercial beekeepers.

{{4}}: Well, to me at least …

{{5}}: I had a ferry to catch and it was getting late.

{{6}}: At the very least I’d learn that this wasn’t a good idea if it all went Pete Tong.

{{7}}: Spanish, French, Dutch, Corsican, Welsh and my feelings about the situation.

{{8}}: And, in a stroke of Holmesian logic, I presumed the …

{{9}}: Doing it this way reduces the chances of crushing bees on the bottom of the frames or the lower edges of the box.

{{10}}: And the following morning made up a nuc with her.

{{11}}: As an aside, virgin queens can fly very well … they have been documented flying at least 5 miles to drone congregation areas. A few laps of a 16 x 8 shed is no challenge at all.

{{12}}: Though I say so myself!

{{13}}: Scissors and Posca pen were nearby, but long and painful experience has taught me not to keep scissors in my beesuit pocket.

{{14}}: Actually, not typical catatonia, which is characterised by abnormal movements, immobility, behaviours, and withdrawal, though the term catatonic is often used to mean unresponsiveness

{{15}}: And I’d used the ‘spare’ virgin queen so had no plan B to revert to had things gone wrong.

{{16}}: It’s also worth noting that determining that the mutation is present would require sequencing the relevant part of the queen’s genome … itself a rather destructive process that induces an irreversible immobility. Or I could wait for a few weeks and sequence some drones from her.

{{17}}: Interesting for me … I’m not sure she’ll be quite so engrossed with the whole process.

Join the discussion ...