Eating my words

I periodically look at the access statistics of this site. It gives me an idea of what’s popular, which subjects might be worth revisiting and which posts have sunk without trace into bottomless void of the internet.

Daily page views are only 50% what they were in June. Maybe it’s the chaos/excitement/disappointment (delete as appropriate) of the US election or the deja vu and crushing inevitably of Lockdown 2.0, but beekeeping appears to be getting less popular.

Or perhaps it just reflects the fact that it’s the end of the season and everyone is frantically catching up on all the tasks they postponed from earlier in the year when they were in the apiary {{1}}.

That’s not to say that there is no beekeeping to do at this time of the year.

Mite corpses

I usually use Apivar for Varroa control. The active ingredient, amitraz, remains effective. I like Apivar as it works even at the lower temperatures we have in Scotland. In addition, the queen continues laying – in contrast to Apiguard for example – at precisely the time the colony needs to be rearing lots of long lived winter bees.

I insert the Apivar strips as soon as the summer honey supers are removed and at the same time as the autumn fondant blocks are added. This year the strips went in on the 28th of August. The mite drop is then monitored over subsequent weeks.

Or should be.

My continued absence on the remote west coast meant that the counts of mite corpses were a bit hit and miss this year {{2}}.

The counts were sufficient to determine the relative mite infestation levels and observe how they dropped over time. Unfortunately, they weren’t detailed or frequent enough to see real differences on a day-by-day basis.

I’d hoped to get this to discuss the influence of the reducing laying rate of the queen on apparent mite infestation levels, but that will have to wait until another year.

Mite drop data

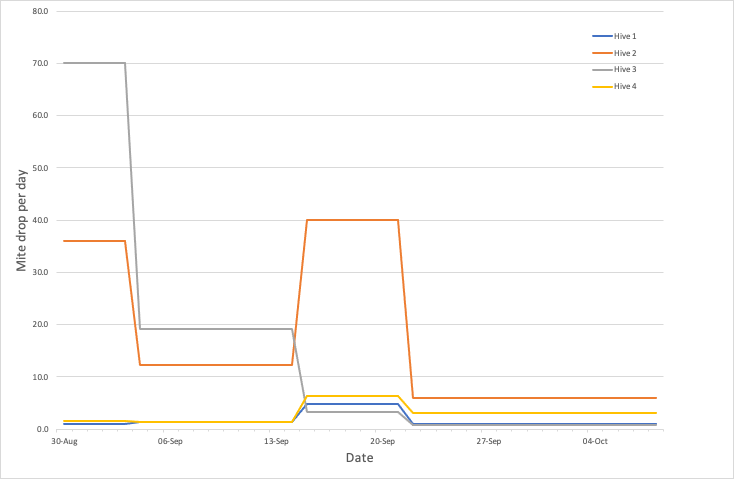

The four colonies plotted on the graph above are in our bee shed. They are all within 4 metres of each other, and have been for at least a year. None have had any Varroa management this season {{3}} other than the Apivar added in late August.

One of the colonies (#1) has had sealed brood periodically removed for experiments. Hive #2 and #4 are on a double brood box, the other two are on singles. All the hives are Swienty or Abelo (poly) Nationals.

The first thing to notice is that there are very significant differences in cumulative mite drop over the first 40 days after starting treatment. Rather than graph these numbers, here’s a simple list by hive number:

- 73

- 697

- 597

- 120

Infestation levels can differ significantly, even in colonies within the same apiary. Or on the same hive stand. Monitoring a single hive as a sentinel for a complete apiary could be very misleading.

Hive #1 counts are probably lower because the colony is a bit weaker than the others (though that’s relatively speaking – many beekeepers would consider it quite strong). However, the drop is not significantly different from #4 which is a very strong colony.

Throughout the treatment period shown (we stopped counting in October) the average mite drop per day from #1 and #4 never exceeded 5 which is satisfying low. There’s little else to say about these two colonies {{4}}.

The high mite drop from colonies #2 and #3 is about as high as I’ve ever seen in my own hives in Scotland.

Mite reductions

When I lived in the Midlands I saw higher counts. There’s a much higher density of apiaries and beekeepers there than in Fife, and it was more difficult to manage colonies to routinely have low mite numbers. I’ve always assumed this was due to robbing and drifting – isolation definitely helps – but my Varroa management was also a bit different (in both method and timing).

Hive #3 trace shows a typical reduction week on week over the treatment period. High at the start and negligible after about 40 days.

Colony #2 has a strange increase in mite drop in the third week of treatment. I don’t really understand this. One possibility is that the colony was robbing a nearby heavily-infested colony {{5}} during this period, with the foragers bringing back phoretic mites as well as the stores they’d robbed out.

In both these “high mite” colonies the mite drop after ~40 days was averaging 5 per day or less, which should be OK. They will be monitored again in mid/late November and after treatment with Api-Bioxal during a broodless period.

For reference, colony #1 was broodless when checked on the 13th of October, a few days after the last count on the graph above.

Apivar strip removal

The approved duration of treatment with Apivar is 6-10 weeks. I usually remove strips after 6 weeks if the mite drop is low and steady. There’s nothing to be gained from overtreating.

However, since I was aware of the high mite drop from colonies #2 and #3 I left the strips in for a bit longer, removing them on the 30th of October (i.e. 9 weeks).

If beekeepers are to avoid Varroa acquiring resistance to Apivar it is very important that the miticide is used properly. Removing the strips within 10 weeks very important.

I attended an online Q&A session with Luis Molero (Scotland’s lead Bee Inspector) organised by the SBA. In this he described finding hives on heather moors which still contained Apivar strips. These had presumably been left in the hive after a mid-season treatment, though whether by accident or design is unclear.

This is poor practice on two counts; continued presence of low levels of the miticide would contribute to selecting amitraz-resistant mites and there is the additional risk of tainting the honey with miticide.

Reading and writing

I spend a lot of my week stuck in the office reading and writing. Grants, manuscripts, strategy documents, complaints, the BBKA Q&A page, menus (well, OK, not menus … and relatively few complaints) etc.

As a consequence I rarely spend much time reading for pleasure. Months go by without me opening The Scottish Beekeeper, the BBKA Newsletter or ABJ. However, as the beekeeping season draws to a close I have a bit more free time and so periodically binge-read some of these to catch up.

Usually, by the time I read something, it’s out-of-sync with the season. I find myself reading about queen rearing strategies in late October, or overwintering queens in early February. Much of this is promptly forgotten … unless I make notes and write about it here.

You could consider The Apiarist as a sort of aide memoire for this forgetful beekeeper ?

However, a few weeks ago I read a letter to the editor in The Scottish Beekeeper on the perils of feeding fondant. I’ll paraphrase here both to avoid copyright issues and because I’ve lost (!) the particular issue the letter appeared in.

The gist of the letter was that the correspondent had lost several colonies when fondant had gone sloppy and dripped down between the frames, killing the colony in the middle of the winter.

I sent a letter to the editor saying that I’d only seen this when the colony had perished through disease. Healthy colonies, clustering under unfinished fondant blocks, tended to keep nibbling away and so were not swamped by a tsunami of cold, syrupy fondant.

Or words to that effect.

Don’t speak write too soon

I’ve got a couple of Varroa-free colonies on the west coast of Scotland. Both were started from nucs in mid/late summer, built up well and collected a reasonable amount of nectar from the heather. I left this for them, nadiring the partially-filled super and – as I usually do – adding a block of fondant on a queen excluder.

Both colonies are in Abelo poly hives with open mesh floors and a 5cm block of Kingspan insulation under the polystyrene roof. This is typically how my colonies would overwinter {{6}}.

Neither colony used much more than 6 kg of fondant as both brood boxes had ample stores. I therefore intended to remove the unused fondant ‘at some point’.

For a future post here I wanted a photograph of the typical ‘stripes’ of brood cappings visible on a Varroa tray. Since these west coast colonies brood later in the season than my Fife bees I inserted a tray below one colony a couple of weeks ago.

‘At some point’ turned out to be today (5th of November).

To my surprise. the underside of the fondant block in the hive with the Varroa tray was distinctly soft and sloppy.

In contrast, the other colony was much as I’d expected. No sticky fondant.

Clearly, under certain conditions, a fondant block can soften sufficiently to start to dribble down between the frames. It’s worth emphasising the colonies are in the same type of hive (floor, boxes and roof), in the same apiary and are of equivalent strength. The only difference is the presence of a well-fitting Varroa tray in one of them.

Eat my words

I think the explanation for the difference from a) my previous experience, and b) between the two hives pictured above, is straightforward.

It rains a lot on the west coast. In the last fortnight we’ve had 280 mm of rain, with today being the first mainly dry day {{7}}. This was why I’d chosen today to remove the fondant.

With that much rain the humidity levels are also quite high. With the Varroa tray in place I suspect that that humidity levels within the hive were higher still. Under these conditions I suggest that the fondant absorbs water faster than the bees can consume/store it.

These conditions are quite specific and are only likely to be an issue for beekeepers (or bees!) living in areas of high and regular rainfall. The original letter to The Scottish Beekeeper was from a beekeeper in Dumfries and Galloway.

Fife and the Midlands – the only areas I have many years experience of beekeeping in – both have less than 750 mm of rainfall per annum. I’ve had hives with both fondant and Varroa trays in place for weeks without any problems.

In my letter to The Scottish Beekeeper I described the hive insulation but failed to mention the open mesh floor. D’oh!

It’s now time to quickly write a follow up to explain these recent observations.

This example rather neatly demonstrates the influence of local conditions … and the importance of trying to interpret what you see when opening a hive.

Since I’ve now written about it (my aide memoire for a forgetful beekeeper ? ) I’ll hopefully also remember this lesson next winter.

Speaking

It’s turning out to be a busy winter for talks to beekeeping associations.

These are increasingly popular as association members realise the benefits they offer.

You don’t have to negotiate icy roads in the dark to sit for an hour in a draughty church hall.

No longer do you have to squint at an image projected onto a creamy-yellow wall with an irritating picture hook in the middle of every slide.

You can sit in the comfort of your own lounge (or bath), sipping shiraz and occasionally staring at a nice picture on a high resolution screen.

At least, that’s what I’m doing … as well as talking a bit ?

I still lament the lack of homemade cakes.

However, I have taught myself to make pizza during lockdown.

If I’m mumbling a bit when I’m talking you’ll know why ?

{{1}}: I’ve spent half of the last week up ladders doing precisely that.

{{2}}: And I’m grateful to Luke in my lab for collecting some of the numbers.

{{3}}: Which includes no enforced brood breaks (other than swarm control), no drone brood uncapping/removal etc.

{{4}}: We’ve also monitored the virus load (DWV) in these colonies and it is very low.

{{5}}: There are other hives in the apiary and several nearby apiaries within range.

{{6}}: Or, for that matter, spend the entire season.

{{7}}: Have you noticed that weather forecasters use the phrase mainly dry to mean ‘rain’ without actually saying ‘rain’?

Join the discussion ...