Cut more losses

This is a follow-on to the post last week, this time focusing on feeding and a few ‘odds and sods’ that failed to make it into the first 3000 words on reducing overwintering colony losses.

Both posts should be read in conjunction with one (or more {{1}} ) of my earlier posts on disease management for winter. Primarily this involves hammering down the mite levels before the winter bees are produced, so ensuring their longevity.

But also don’t forget to treat your colonies during a broodless period in midwinter to mop up mites that survived the autumn treatment, or have reproduced since then.

Why feed colonies?

All colonies need sufficient stores to get the colony through the winter until suitable nectar sources and good enough weather make foraging profitable the following spring.

How much the colony needs depends upon the bees themselves – some strains are more frugal than others – and the duration of the winter. If there is no forage available, or the weather is too poor for the bees to fly, then they will be dependent upon stores in the hive.

A reasonable estimate would probably be somewhere around 20 kg of stores, but this isn’t a precise science.

It’s better for the colony to have too much than too little.

If the colony has stores left over at winter’s end you can always remove them and use them when you make up nucs later in the season. Just pull out the frames and store them safely until needed.

In contrast, if the colony starts the winter with too few stores there are only two possible outcomes:

- the colony will starve to death, usually in late winter/early spring (see below)

- you will spend your winter having to regularly check the colony weight and opening the hive to add “emergency rations” to get them through the winter

Neither of these is desirable, though you should expect to have to check the colony periodically in winter anyway.

Feeding honey for the winter … and meaningless anecdotes

By the end of the summer the queen has reduced her laying rate and the bees should be backfilling brood comb with honey stores. If you assume there’s about 5 kg of stores {{2}} in the brood box then they’ll need about another 15 kg.

15 kg is about the amount of honey you can extract from a well-filled super.

Convenient 😉

Some beekeepers leave a full super of honey on the hive, claiming the “it’s better for the bees than syrup”.

Of course, it’s a free world, but there are two things wrong with doing this:

- where is the evidence that demonstrates that honey is better than sugar-based stores?

- it’s an eye-wateringly expensive way to feed your colonies

By evidence, I mean statistically-valid studies that show improved overwintering on honey rather than sugar.

Not ‘my hive with a honey super was strong in spring but I heard that Fred lost his colony that was fed syrup’ {{3}}.

That’s not evidence, that’s anecdote.

If you want to get this sort of evidence you’d need to start with a lot of hives, all headed by queens of a similar age and provenance, all with balanced numbers of brood frames/strength, all with similar mite levels and other pathogens.

For starters I’d suggest 200 hives; feed 50% with honey, 50% with sugar … and then repeat the study for the two following winters.

Then do the stats {{4}}.

The economics of feeding honey

The 300 supers of honey used for that experiment would contain honey valued at about £80,000.

That’s profit, not sale price (though it doesn’t include labour costs as I – and many amateur beekeepers – work for free).

The honey in a single full super has a value of £250-275 … that’s an expensive way to feed your bees {{5}}.

Particularly when it’s not demonstrably better than a tenner or so of granulated sugar 🙁

But there are more costs to consider

The economic arguments made above are simplistic in the extreme. However, there are other costs to consider when feeding colonies.

- time taken to prepare and store whatever you will be feeding them with {{6}}

- feeders needed to dispense the food (and storage of these when not in use)

- energetic costs for the colony in converting the food to stores

Years ago I stopped worrying (or even thinking much) about any of this and settled on feeding colonies fondant in the autumn.

Fondant is ~78% sugar, so a 12.5 kg block contains about 9.75 kg of sugar.

This year I’m paying £11.75 for fondant which equates to ~£1.20 / kg for the sugar it contains.

In contrast, granulated sugar is currently about £0.63 / kg at Tesco.

The benefits of fondant

Although my sugar costs are about double this is a relatively small price I’m (more than) prepared to accept when you take into account the additional benefits.

- zero preparation time and no container costs. Fondant comes ready-wrapped and stores for years in the box it is purchased in

- no need for jerry cans, plastic buckets or anything to prepare or store it in before use

- no need for expensive Ashforth-type feeders that sit around for 95% of the year unused When I last checked an Ashforth feeder cost £66 😯

- it takes less than 2 minutes to add fondant to a colony

- no risk of spillages – in the kitchen, the car or the apiary {{7}}.

- fondant is taken down more slowly than syrup, so providing more space for the queen to continue laying. In addition, in the event of an early cold snap, fondant remains accessible whereas bees often stop taking syrup down

Regarding the energetic costs for the colony in storing fondant rather than syrup … I assume this is the case based upon the similarity of the water content of fondant to capped stores (22% vs. 18%), whereas syrup contains much more water and so needs to be ripened before capping to avoid fermentation.

Whether this is correct or not {{8}}, the colony has no problem taking down the fondant over a 2-4 week period and storing it.

What are the disadvantages of using fondant?

The only one I’m really aware of is that the colony will not draw fresh comb when feeding on fondant (or at least, not enthusiastically). In contrast, bees fed syrup in the autumn and provided with fresh foundation will draw lovely worker brood comb.

Do not underestimate this benefit.

Brood frames of drawn comb are a very valuable resource. Every time you make up a nuc, or shift a nuc to a full-sized box, providing drawn comb significantly speeds up the expansion of the resulting colony.

Nevertheless, for me, the advantages of fondant far outweigh the disadvantages …

Finally, in closing, I’ve not purchased or used invert syrup for feeding colonies. Other than no prep time this has the same drawbacks as syrup made from granulated sugar. Having learnt to use fondant a decade or so ago from Peter Edwards (Stratford BKA) I’ve never felt the need to look at other options.

Let’s move on …

Ventilation and insulation

Bees can withstand very cold temperatures if healthy and provided with sufficient stores. In northern Canada bees may experience only 120 frost-free days a year, and cope with 3-4 week periods in winter when the temperature is -25°C (and colder if you consider the wind chill).

That makes anywhere in the UK look positively balmy.

I’ve overwintered colonies in cedar or poly boxes for a decade and not noticed a difference in survival rates. Like the honey vs. sugar argument above, if there is a difference it is probably minor.

However, colony expansion in poly boxes in the spring is usually better in my experience, and they often fill the outer frames with brood well before cedar boxes in the same apiary get there.

Whether cedar or poly I take care with three aspects of their insulation/ventilation:

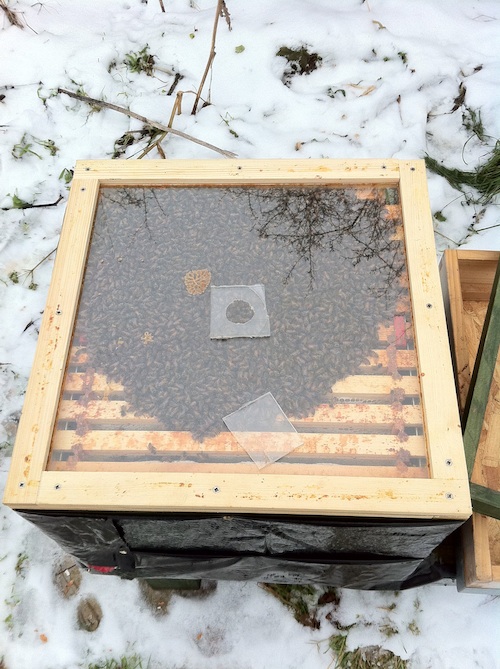

- the colonies have open mesh floors and the Varroa tray is only in place when I’m actively monitoring mite drop

- all have insulation above the crownboard in the form of a 50 mm thick block of Kingspan (or Recticel, or Celotex), either integrated into the crownboard itself, placed above it or built into the roof

- I ensure there is no upper ventilation – no matchsticks under the crownboard, no holes etc.

- excess empty space in the brood box is reduced to minimise the dead air space the bees might lose heat to

In my experience bees actively dislike ventilation in the crownboard. They fill mesh with propolis …

… and block up the holes in those over-engineered Abelo crownboards …

Take notice of what the bees are telling you … 😉

Insulation over the colony

I’ve described my insulated perspex crownboards before. They work well and – when inverted – can just about accomodate a flattened {{9}}, halved block of fondant.

Finally, if it’s a small colony in a brood box {{10}} then I reduce the dead space in the brood box using a fat dummy.

I build these filled with polystyrene chips.

You don’t need this sort of high-tech solution … some polystyrene wrapped tightly in a thick plastic bag and sealed up with gaffer tape works just as well.

I’ve even used bubblewrap or that air-filled plastic packaging to fill the space around a top up block of fondant in a super ‘eke’ before now.

However, remember that a small weak colony in autumn is unlikely to overwinter as well as a strong colony. Why is it weak? Would you be better uniting it before winter starts?

Nucleus colonies

Everything written above applies equally well to nucleus colonies.

A strong, healthy nuc should overwinter well and be ready in the spring for sale or promoting to a full colony.

Although I have overwintered nucs in cedar boxes I now almost exclusively use polystyrene. This is another economic decision … a well made cedar nuc costs about double the price of the best poly nucs.

I feed my nucs fondant in preparation for the winter, typically by adding 1-2 kg blocks to the integral feeder.

Because of the absence of storage space in the nuc brood box it’s not unusual to have to supplement this several times during the autumn and winter.

You can even overwinter queens in mini-mating nucs like Apidea’s and Kieler’s.

This deserves a post of its own. Briefly, the mini-nuc needs to be very strong and usually double- or triple- height. I build fondant frame feeders for Kieler’s that can be quickly swapped in/out to compensate for the limited amounts of stores present in the brood box.

My greatest success in overwintering these was in winters when I provided additional shelter by placing the nucs in an unheated greenhouse. A tunnel provided access to the outside. However, I know several beekeepers who overwinter them without this sort of additional protection (and have done so myself).

Just because this can be done doesn’t mean it’s the best thing to do.

I’d always prefer to overwinter a colony as a 5 frame nuc. The survival rates are much better, their resilience to long periods of adverse weather is significantly greater, and they are generally much more useful in the spring.

Miscellaneous musings

Hive weight

A colony starting the winter with ample stores can still starve if the bees are particularly extravagant, or if they rear lots of brood but cannot forage.

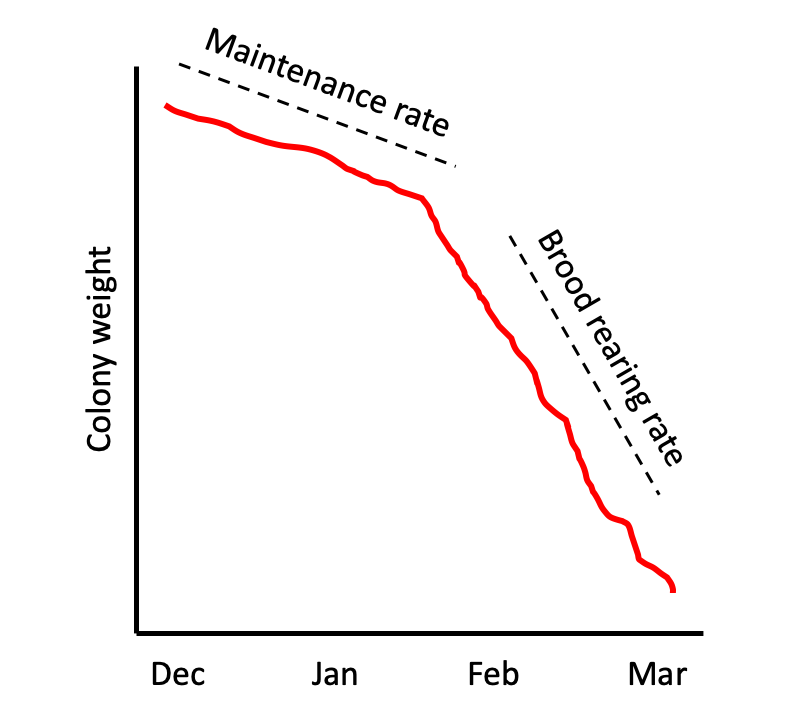

The rate at which stores are used is slow late in the year and speeds up once brood rearing starts again in earnest early the following spring (though actually in late winter).

As should be obvious, this is a Craptastic™ sketch simply to illustrate a point 😉

The inflection point might be mid-December or even early February.

The important message is that, once brood rearing starts, consumption of stores increases. Keep checking the colony weight overwinter and supplement with fondant as needed.

I’m going to return to overwinter colony weights sometime this winter as I’m dabbling with a weather station and set of hive scales … watch this space.

An empty super cuts down draughts

Periodically it’s suggested that an empty super under the (open mesh) floor of the hive ‘cuts down draughts’, and is therefore beneficial for the colony.

It might be.

But like the ‘overwintering on honey’ (and being a pedant scientist) I’d always want to see the evidence.

There are two claims being made here:

- a super under the floor cuts down draughts

- fewer draughts benefits the colony which consequently overwinters better

Really?

There are ways to measure draughts but has anyone ever done so? Remember, the key point is that the airflow around the winter cluster would be reduced if there are fewer draughts.

Does a super reduce this airflow significantly over and above that already caused by the sidewalls of the floor?

And, even if it does, perhaps the colony ‘reshapes’ itself to accommodate the draught from an open mesh floor.

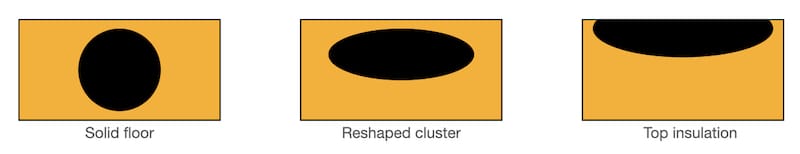

For example, in an uninsulated hive (including no insulation over the cluster) with a solid floor the cluster is likely to be roughly spherical. They minimise the surface area.

With an open mesh floor are they more ellipsoid, so avoiding draughts from below? If so, is this improved much by an empty super below the open mesh floor? Does the cluster change shape or position? I don’t know as I’ve not compared cluster shapes in solid vs. open mesh floors plus/minus a super underneath.

And anyway, an open mesh floor looks very like a baffle to me … how much better can it get? How draughty is it in the first place?

Is this example 8,639 for my ‘Beekeeping Myths’ book?

I do know that top insulation tends to flatten the cluster against the warm underside of the crownboard.

Having worked out that draughts are (or are not) reduced … you still need another couple of hundred hives to test whether overwintering success rates are improved!

More winter bees

Finally, always remember that the survival of the colony is dependent upon the winter bees. All other things being equal (stores, disease etc.), a colony with lots of winter bees will overwinter better than one with fewer.

This is one of the reasons I stopped using Apiguard for mite control in autumn. Apiguard contains thymol and quite regularly (30-50% of the time in my experience) stopped the queen from laying, particularly in warmer weather.

Apiguard works well for mite control, but I became wary that I was potentially stopping the queen at a time critical for late-season colony development. I worried that, once treatment was finished, a cold snap would shut down brood rearing leaving it with suboptimal numbers of winter bees.

I never checked to see whether the queen ‘made good’ any shortfall after removal of the treatment … instead I moved to Scotland where it’s too cold to use Apiguard effectively 🙁

{{1}}: Go on … treat yourself!

{{2}}: And I’ve not measured it, so this is very much a guesstimate.

{{3}}: Maybe Fred is a lousy beekeeper? Perhaps he didn’t control mite levels? Maybe the colony was destroyed by a woodpecker?

{{4}}: And even then you might well not have enough hives in the study. If there is a difference I suspect it will be very, very slight … so necessitating large numbers of colonies to generate statistically valid results.

{{5}}: All I’m considering here is 15 kg of honey sold (minus costs of jarring and labelling) for about £6 for 340 g … ((300 x 15,000)/340) x 6 = £79,400. Yes, I know there are many other costs involved … I’m using a bit of artistic licence and simply trying to emphasise the point that honey is an expensive way to feed your bees.

{{6}}: I realise I excluded time from my costs estimates above, but now I’m including it … it’s my blog, I can do what I want :-)

{{7}}: The last of these reduces the opportunities for robbing, the middle one keeps my vehicle slightly less messy than it would otherwise be and the first saves my marriage.

{{8}}: And I’m happy to be corrected …

{{9}}: Stand on it to achieve sufficient ‘flatness’.

{{10}}: Which I should have united before autumn … take your losses before winter.

Join the discussion ...