All together now

This is the last of a short series of related posts on rational Varroa control. It brings together the key points made on the choice of how and when to treat, coupled with a treatment strategy that minimises the influence of bees drifting between colonies. The latter is best summarised in three words … coordinated Varroa treatment.

Coordinated Varroa treatment makes sense

Abandoned hives …

Most beekeepers treat their own colonies together … it’s logical, easier and cost effective. But what about the other beekeepers in the shared association apiary? What about the colonies two gardens away? What about the large row of colonies in the bottom of the adjacent field? What about that abandoned hive in the hedgerow over the road? What about the feral colony in the church tower? All of these are a potential source of reinfestation. After a week or two of miticide treatment your own colonies are likely to be largely free of phoretic mites … but all those nearby untreated (or yet to be treated, or ineffectively treated … or just plain forgotten) colonies can act as a source of mites and viruses from drifting workers and drones. These will infest and infect your colonies. Robbing bees – not the maelstrom of foragers ripping a colony apart that most beekeepers would recognise, but the silent robbing that can occur largely unseen and unsuspected in many apiaries – will bring a smorgasbord of virus-loaded mites and workers to your recently-treated hives. Remember also, your colonies may well be robbing other untreated, mite-infested colonies nearby. If all colonies ‘within range’ (see below) were treated at the same time these bee behaviours (drifting, robbing) that cannot be altered would have far less impact in transferring mites and viruses.

Coordinated Varroa treatment – over a wide geographic area – hasn’t been widely investigated in the UK. In Europe there have been a number of coordinated treatment trials, for example in isolated mountain valleys, where the geography provides a barrier to bee movement. Due to the unregulated and often undocumented nature of beekeeping in the UK it may well be more difficult to organise effectively. However, this isn’t a reason coordinated Varroa treatment shouldn’t be attempted. There are precedents in the salmon farming industry where all cages within a single water catchment area must be coordinately treated – both in terms of time and (I believe) the compound(s) used for controlling sea lice. This isn’t voluntary because it’s been shown to be effective.

What’s ‘within range‘?

One mile radius …

Drifting of foragers and robbing etc. are distance-dependent activities. The more widely separated colonies are, the less likely they are to be an issue. This was amply demonstrated in the recent comments by Tom Seeley that feral colonies hived and co-located in apiaries succumbed to mite-transmitted virus infections, whereas those sited – individually – at least 30 metres apart had lower mite counts and survived better (Sharashkin, L [2016], ABJ 156:157). So perhaps all colonies within 30 metres should be treated together?

Clearly this is too low a limit. Firstly, we know bees can travel much further and the studies described by Seeley didn’t test whether colonies survived even better if spaced even further apart. Secondly, the feral colonies Seeley studies are naturally located approximately half a mile apart from each other. Whilst this is undoubtedly influenced by the availability of hollow trees it suggests that the range could usefully be extended to at least half a mile. I’ve certainly seen robbing occurring between colonies located at least 500 metres apart.

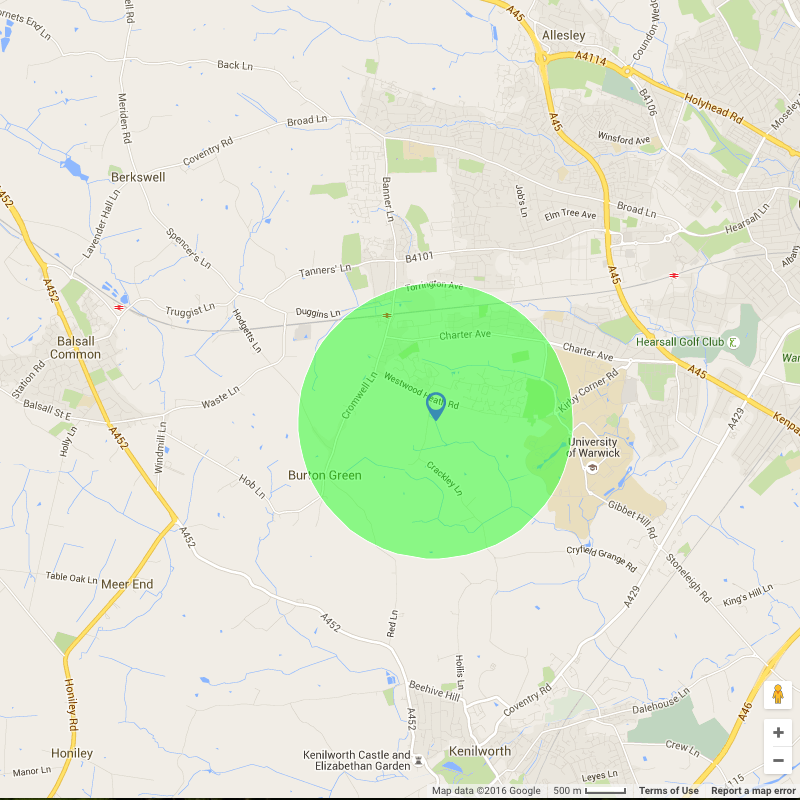

Since the effective limit over which re-infestation might occur isn’t known it perhaps make sense to throw the net a little more widely … a mile for example? This is a convenient distance … covering most beekeepers within a small village in a rural area, those sharing adjacent fields in farmland or perhaps a number of urban apiaries. It’s also a manageably small area, where personal contact and friendly agreement should be sufficient to coordinate treatment. Do you know the location of all of the colonies within a mile of your own? Google maps can help. So can local association membership, or simply accosting people you see wearing a beesuit. I knew of ~20 hives belonging to 4-5 beekeepers within a mile of my previous home apiary. Of course, with any sort of migratory beekeeping – bringing colonies back from the heather, taking them to orchards – or simply moving nucs from a split colony to a new apiary, there’s a possibility of colonies with low mite levels getting exposed to colonies with a high level of infestation. For proper coordinated treatment these movements would have to be taken account of.

In our bee virus research we’re investigating the benefits of large scale coordinated Varroa treatment by working with all the beekeepers on a large island, where the sea provides a natural barrier to mites entering the test area. Over the next three years we will see how mites, and more importantly the viruses they transmit, are controlled by coordinating Varroa treatment within this defined area.

Coordinated Varroa treatment helps mitigate the effects of drifting and robbing between colonies, activities that are usually underestimated and that are known to transmit mites and (inevitably) viruses and other pathogens. This isn’t rocket science. It’s a logical response to the biology of bees and the pathogens that they carry.

How to treat

Spot the difference …

Use a miticide that is appropriate for the conditions, use it according the manufacturers instructions and keep records of the treatment. There are no hard and fast rules, but it’s worth taking account of the following:

- Avoid using pyrethroid-based miticides if there’s any evidence of resistance. Just because you get a high mite drop with Apistan doesn’t mean there isn’t an even larger resistant population left infesting your colony¹ … there are ways of checking this, perhaps you should?

- Avoid using Apiguard unless the temperature really is high enough for it to work effectively, which means an average of 15°C for a month. If used at a sub-optimal temperature you’ll be leaving mites behind …

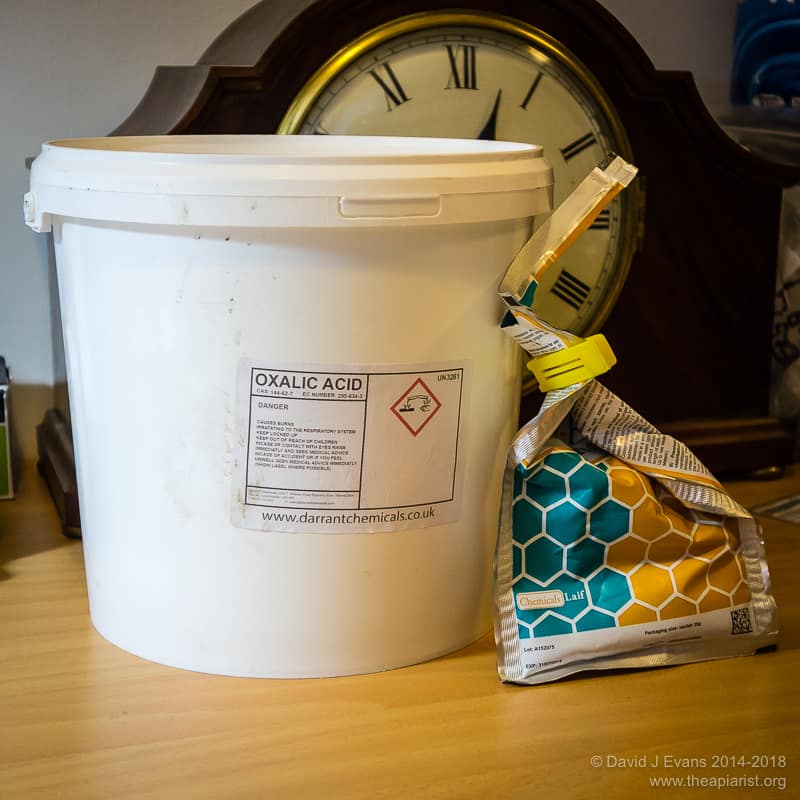

- Avoid trickling oxalic acid/Api-Bioxal if there’s brood (sealed or unsealed) in the colony. It’s toxic to unsealed brood and the mites in sealed brood will escape unscathed …

- Avoid vaporising Api-Bioxal unless you enjoy cleaning the gunky mess™ from the vaporiser. If vaporising oxalic acid ensure that the colony is broodless, or be prepared to repeat treatment three times at five day intervals to catch both phoretic and emerging mites …

- Be aware that some miticides stop the queen from laying. Perhaps try and avoid these when you’re dependent on the colony raising the all-important winter bees that are going to get it through to the following Spring. I don’t actually know how much of an issue this is for colony health and survival, but it always concerned me when the queen went on a go-slow at the very time I wanted her to keep laying strongly through late August/early September.

- Don’t reduce treatment doses or times … partial treatments are partially effective. This is also a great way to select for miticide-resistant Varroa (though whether they arise depends upon the mechanism of action – resistance to oxalic acid, formic acid and thymol has not been observed).

When to treat

Bee working ivy …

Earlier than you perhaps think to protect the winter bees from viruses. When I lived in the Midlands I would treat immediately after taking the summer honey crop – perhaps mid/late August. There’s later forage available – himalayan balsam and ivy – both of which some beekeepers either like or have a market for, but collecting it risks exposing the developing winter bees to high levels of Varroa and pathogenic viruses. Now I live in Scotland I’m going to have to develop alternative treatment schedules for colonies going to the heather – brood breaks and/or creative use of a vaporiser in June/July.

Treatment is only part of the solution though …

These articles on Varroa control have focused almost exclusively on miticide treatment. There are also a range of beekeeping practices that can contribute significantly to effective Varroa control, reducing the necessity to treat with chemicals. These include enforced brood breaks, shook swarms, drone brood uncapping, queen trapping and others. A proper integrated pest management strategy involves both chemical and beekeeping interventions to prevent the build up of dangerously high mite levels in the colony. Some of these will be covered in more detail during the coming season.

¹I think there’d be a case to ban the sale and use of Apistan for three years out of every four … pyrethroid resistance in mites appears to be detrimental in the absence of selection i.e. resistance is lost if the miticide is not used for a few years. That way, when used it would be devastatingly effective. This compares to the current situation where Apistan resistance is very widespread, and constantly selected for by continuing use of pyrethroids. Of course, there’s no way to enforce this – despite the fact it would probably be a great benefit for bee health – but now we’re back to the unregulated and undocumented nature of UK beekeeping.

Join the discussion ...