Christmas is coming ...

Synopsis: Beekeepers prepare honey, candles or mead for gifting at Christmas, but what should a non-beekeeper get for a beekeeper?

Introduction

“Christmas is coming, the goose is getting fat”, to quote the traditional nursery rhyme and Christmas song.

Well, I can’t vouch for their corpulence, but my late season beekeeping visits to Fife are accompanied by skeins of pink-footed geese arrowing overhead as they arrive from Greenland for the winter. Their distinctive wink-winking flight calls can be heard well before the straggly flying V formations can be seen. They are an annual reminder that, however hard the winter is in Scotland, it’s a lot more severe further north.

I checked the forecast for the appropriately named (for a beekeeping website) Nuuk on the west coast of Greenland. It’s -3°C there at the moment … slightly warmer than it is here. Nuuk residents are enjoying the unseasonably warm late autumn weather and bracing themselves for the next four months when the temperature averages about -9°C.

No wonder the geese fly south.

There’s been only one visitor to The Apiarist from Greenland in 2023, perhaps this ‘namecheck’ will attract more. I’ve also used a bit of artistic licence. Greenland Beekeeper’s Association appears to be located in the balmy south of the country at Narsarsuaq, about 400 km south-east from Nuuk.

My bees are now fed, treated with oxalic acid, strapped down securely and completely self-sufficient for the next couple of months. Brood rearing is likely to start again in the next fortnight but I’m unlikely to do anything – other than periodically check the entrances are clear – until at least mid/late February, and probably later. I don’t usually heft the boxes until brood rearing has picked up a bit.

In the meantime, there’s Christmas to think about.

Gifts

Whether religious or secular, the Christmas holiday is associated with the exchange of gifts. As beekeepers we are fortunate that honey or candles (or mead … if it’s better than mine) are presents welcomed by almost everyone. You can enhance an already unique ‘handmade’ product with a custom made and personalised label. I produce these on my thermal printer, using ‘hi-vis’ marker pens to add red, blue and green highlights for Santa and the sack of presents.

However, a gift for a beekeeper – from a non-beekeeper – can be problematic.

After all, beekeeping can appear like a slightly esoteric pastime.

Well, OK, very esoteric.

It’s a consequence of our enthusiastic willingness to handle thousands of stinging insects, the distinctive and specialised clothing, the smoke, the strange terminology – making increase, slatted racks, ekes and supers.

We might know what we’re talking about, but to the uninitiated it sounds like gobbledegook {{1}}.

So, pity the friends or family who want – or have – to buy a beekeeper a present they will, a) be pleased to receive, b) use and, c) do not already own.

A gift certificate for Thorne’s doesn’t count.

If you’re asked to produce a list then life is easy. If not, drop some hefty hints.

Failing that here’s a list of things that I’ve used over the last season or two that have been particularly noteworthy, a few of which I originally received as gifts.

Some of the items can only be sourced from a specialist beekeeping store, others are available much more widely.

Trickle 2 bottle

Let’s start with a stocking-filler … not everything has to be stainless steel and hideously expensive.

The Trickle 2 bottle makes trickling oxalic acid (OA) solution along a seam of bees a doddle. They change a slightly fiddly task where you are juggling a bowl of OA and a small syringe, whilst simultaneously trying to leave the crownboard off for the minimal period, into a simple, quick and efficient single-handed job.

The bottle has a small upper reservoir that, when full, contains 5 ml of liquid. The lower ‘tank’ accommodates 100 ml. Every time you squeeze the body of the bottle the upper tank fills. You then invert the bottle, emptying the OA along the seam and then repeat.

It takes less time to do it than it takes to read about how to do it.

At £1.31 this is a no-brainer. For the small-scale beekeeper there is no easier way to dispense liquid OA solutions. Commercial beekeepers will use a pressurised backpack/garden spray setup calibrated to deliver 5 ml per second … but I couldn’t afford the Api-Bioxal to fill one of those in the first place.

Of course, receiving this bottle as a present this year means you won’t get to use it until next November … as you should have already completed your OA treatment this winter.

OK, no more nagging!

These small bottles are also ideal for dispensing concentrated glyphosate when using the ‘drill and drop’ method for clearing dense growths of Rhododendron ponticum.

But don’t use the same bottle for both applications.

Bandana

In high summer ladies glow, men perspire and horses beekeepers sweat like pigs {{2}}.

The difference between males and females is described more scientifically as ‘sex differences in thermoeffector responses’ and has been extensively studied. Recent work shows that females sweat less because, typically, they are physically smaller. Males and females with similar physiques both perspire i.e. it’s morphological, not physiological.

I’ve no idea how female beekeepers respond when the sun is beating down and there are two dozen full supers to clear, shift and stack.

However, I do know how I respond.

The combination of 29°C, heavy lifting and a beesuit is tough. I usually wear a peaked cap under my veil, but the sweat perspiration still pours off me. It gets in my eyes, runs down my nose and fills my gloves.

I’ve not solved the last of these symptoms, but wearing a thin bandana underneath my hat largely prevents the first two.

These are available from Amazon and all sorts of other outlets. They cost about £11 for five, at least mine did. Pedantically the ones I use are not true bandanas. These are more properly a square or triangle of cloth tied in place around the neck or head. Instead, mine are made from a thin patterned polyester/spandex material with good ‘wicking’ properties, elasticated so it stays in place and I don’t have to fumble retying it inside a closed veil with a billion bees trying to get in.

You also get to look like a rock god … or just faintly ridiculous.

Kitchen blow torch

The first of three items associated with the near-ubiquitous beekeeper’s smoker.

Smokers are such an integral part of beekeeping that they are – together with the veil – recognised by almost everyone.

However, the trials and tribulations of lighting the smoker are something that only a beekeeper is properly aware of. You don’t have to use a smoker, but if you do use one it is infuriating if it keeps on going out … or takes forever to light in the first place.

An easily lit and dependable smoker involves a combination of three things; a large bodied smoker with good bellows and air flow, suitable fuel (of which there are a million options, the very best being dry, rotten wood, egg boxes, dried grass, cardboard, larch shavings, lavender, hessian … whatever you have available {{3}} ) and a lighter that will work in the depths of the smoker and on a windy day.

For years I used a conventional DIY blow torch. These work well and they are also useful for flaming (sterilising) cedar brood boxes. However, they are large and cumbersome, taking up valuable space in the (already overloaded) bee bag.

Instead I now use a kitchen blow torch designed to produce the perfect finish on a crème brûlée. These run on lighter fuel (butane) and usually have a piezo ignition system. They are small and light and I carry mine together with a box of mixed smoker fuel. Highly recommended and about a tenner.

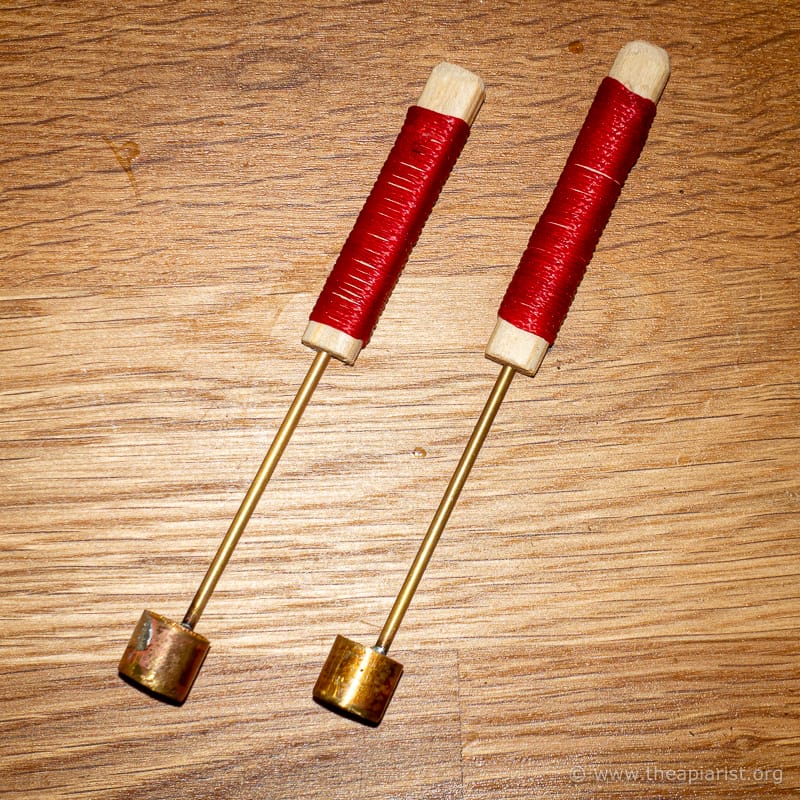

There are other uses for these little blow torches … the flame is adjustable and focused. I used mine to silver solder together the copper shaft and cutting ring on my cell punches.

Probably the best smoker in the world

I’ve used a few smokers over the years, but for the last decade I’ve been using Dadant stainless steel smokers. These are four inches in diameter and either 7 or 10 inches high. The large volume smoker body makes lighting them easy and ensures – with the proper fuel (see above for a list of the best smoker fuels) – that they stay alight.

I started with the shorter smoker but was then generously given the taller model when I left my last-but-one job. They now live in different apiaries so I don’t have to carry a smelly smoker with me in the car all the time. Either model is excellent and should last you a lifetime.

These smokers are not inexpensive … $55-58 in the USA, and up to £80 (I’m confused) in the UK. I’ve not looked exhaustively, but the best prices I’ve found is from Gwenyn Gruffydd.

You won’t regret it … particularly since we’re talking about a gift that someone else pays for.

Smoker box

There’s no smoke without fire.

A smoker gets hot and smelly in use. It stays hot and continues to pong long after you stop using it. Therefore, if you want to transport it, or even store it safely, you need to put it in a fireproof box.

I know some beekeepers who use ex-army ammo boxes, or steel buckets (not ideal as open-topped), but if you can’t find something suitable or want a purpose-made box then have a look at the one sold by Abelo.

This is just big enough for the large Dadant smoker, has a reasonably airtight seal around the inside of the lid and a secure catch. You can put a lit smoker into the box and it will soon go out. In practice you should probably extinguish the smoker first, but at least this shows that the box seal is pretty good.

The model I have has been updated and the new one appears to have protruding hinges and a fixed (rather than fold flat) handle. I’m not sure why the design has changed and I think I prefer the one without stuff jutting out as it packs into the car a bit more easily.

The Abelo box is about £59 – more than many smokers – but should last well. There are other designs; Thorne’s do one with an external ‘pocket’ for hive tools but I’m sure the inevitable rattling would drive me completely bonkers.

OK, enough pyromania, what else?

Stainless steel honey valve

I run my extractor with that valve open, letting the honey run directly through coarse and fine filters into 15 kg buckets. The valve is plastic and drips a bit unless tightened down. However, it’s barely used, so this is irrelevant.

In contrast, when I jar honey, the valve is used for every … single … jar.

Open, adjust fast flow, slow, slower, very slow, stop.

Any subsequent drips before I can remove the filled jar and replace it with a new empty jar significantly slow the bottling process.

These drips are worse if the honey is a little too warm. With soft set honey this is really noticeable {{4}} … the difference between 31°C and 34°C can turn a pleasant 60 minute task into an infuriating 90 minutes of interruptions.

This doesn’t matter if you’re just preparing half a dozen jars, but if there are 120 to fill it starts to make a real difference. Any more than that and I’d have to start saving for a Swienty automatic filling station {{5}}.

On a whim I bought a stainless steel honey valve to replace one of the plastic valves. At £32 it’s over three times the price of a plastic valve, but it has a much cleaner ‘cut off’ and drips – while not totally a thing of the past – are now barely a problem. I’m going to buy a second one for my other bottling tank so I can jar batches of soft set or clear honey without irritating drips.

Perhaps slightly indulgent but it does make a tedious job a little less time-consuming.

What? Not very ‘Christmassy’?

Let’s move on.

Books

The books I’ve enjoyed most this year are about bees, not beekeeping.

Most beekeeping books are largely restricted to already well-covered topics … I’m not sure I can face another tortuous description of Pagden’s artificial swarm. Like most introductory courses for beekeeping, the contents are much of a muchness, only the presentation varies. Consequently my shelves have many more books on bees than on beekeeping.

I write about quite a bit of science in my posts. Typically the work I try and cover is new. Sometimes it’s even original. I’m sure some of the studies discussed will, in time, be considered seminal … cited in coming decades as ‘the first study that showed X’ or ‘a landmark in our understanding of Y’.

But, most will disappear without trace or – at best – be used as filler to support a more recent study of the same topic that shows much the same thing.

Science tends to move forwards in incremental, faltering steps. My posts tend to discuss the steps, not the overall journey.

For the latter you need a retrospective view and some contextual information.

The dancing bees

Like the veil and the smoker, even non-beekeepers are aware of the waggle dance used by bees to communicate the location of pollen and nectar. It’s largely taken for granted now, though it remains the only form of invertebrate communication we understand.

Karl von Frisch won the Nobel prize for decoding the waggle dance in 1973. Tania Munz, a historian of science, has written a comprehensive biography of von Frisch, documenting both his scientific studies, the context in which they were undertaken – Nazi Germany – and the problems that this caused. Recommended.

The Dancing Bees: Karl von Frisch and the Discovery of the Honeybee Language by Tania Munz, 2016, ISBN 9780226020860 University of Chicago Press £24 {{6}}

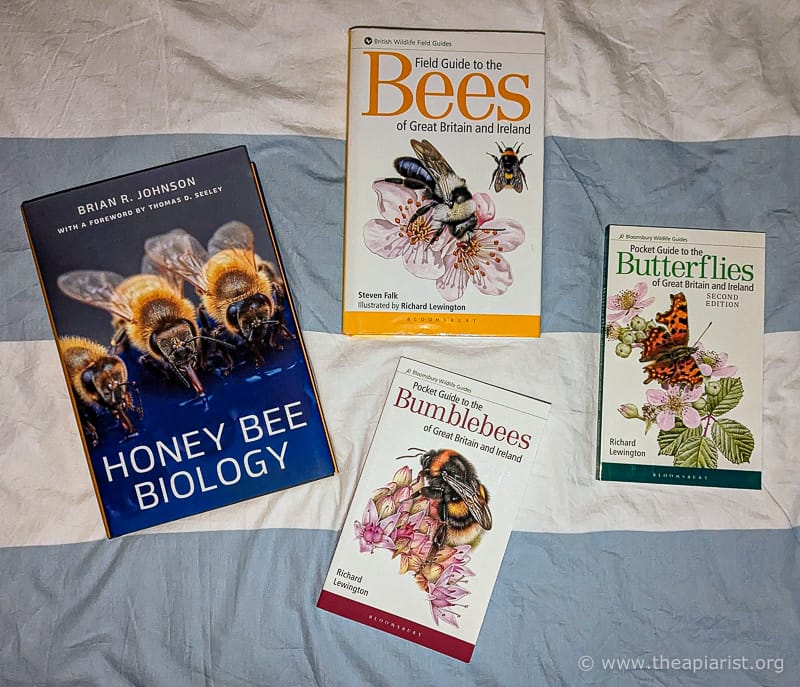

Honey bee biology

I mentioned this book earlier in the year. If you don’t want to tackle primary scientific papers but are still interested in understanding the biology of the honey bee then this is a good place to start. Brian Johnson covers pretty much everything; genetics, physiology, neurobiology, behaviour and development.

It’s heavily referenced and a dense read, perhaps better for dipping in and out of, rather than reading it cover to cover. There’s a reasonably comprehensive index. If you didn’t progress further than ‘O’ level biology then perhaps look elsewhere, but you don’t need two PhD’s and a brain the size of a planet for most of the book.

Honey bee biology by Brian R Johnson, 2023, ISBN 9780691204888 Princeton University Press £38

Field guides

Honey bees are (wrongly) the poster-child for pollinating insects. If you believe the popular press, or any number of commercial ‘sponsor a beehive’ ‘beewash’ companies, they’re the only bee that does any pollination.

They’re not.

There are hundreds of other species in the UK, and thousands more globally. Since it’s useful to be able to recognise some of the native bees that our bees share the environment with – and compete for resources in – I’d recommend two field guides.

Pocket Guide to the Bumblebees of Great Britain and Ireland by Richard Lewington, 2023, ISBN 9781472993595 Bloomsbury Publishing £11 (paperback … and currently 30% off and ~£7.60!)

Field Guide to the Bees of Great Britain and Ireland by Steven Falk, 2015, ISBN 9781910389027 Bloomsbury Publishing £50

Anything by Thomas Seeley

Thomas Seeley is an excellent scientist and a great communicator. If Brian Johnson’s book (above) is too ‘sciency’ then I’d recommend any of the books by Seeley that are currently in press. The breadth of coverage is less; Honeybee Democracy deals with nest site selection by swarms and The Lives of Bees discusses details of free living honey bees. Both are outstanding; well written, beautifully illustrated and very interesting. There’s just as much science as Honey bee biology, albeit on a narrower range of topics, but it’s a lot more accessible.

Honeybee Democracy by Thomas Seeley, 2010, ISBN 9780691147215 Princeton University Press £25

The Lives of Bees by Thomas Seeley, 2019, ISBN 9780691166766 Princeton University Press £25

Finally, if you’re interested in finding ‘wild’ colonies {{7}} then Following the Wild Bees: The Craft and Science of Bee Hunting is an enjoyable read {{8}}. Published in 2016, ISBN 9780691170268 Princeton University Press £19

bru travel mug

It was bitterly cold in the apiary today, though eased a little by the dazzling late morning sun hanging close to the horizon. If I’m working outdoors in the winter I like to take a hot drink with me and use a bru travel mug.

These have a ceramic lining, are reasonably well insulated and have a craftily-designed leakproof lid operated with one finger … push-to-drink then push-to-seal. These mugs are ideal for car journeys. The medium (340 ml) is about the same volume as a latte in most coffee shops and you should get a discount for not using a disposable cardboard cup.

Last minute gifts for beekeepers

By ‘last minute’ I mean online and delivered digitally …

Beekeeping is an international pastime and it’s entertaining and informative to learn how beekeepers in other countries manage their bees. The bees are the same, but the environment and management methods are often very different.

If you want to see how they mismanage them there’s some great stuff on YouTube.

I’ve subscribed to the American Bee Journal for many years. They’ve got some great regular columnists and it provides a fascinating insight into beekeeping ‘over the pond’. A digital subscription costs $16 (~£12.60) a year.

Remember that even non-subscribers can view archived digital back issues of ABJ that are one or more years old.

For US readers you could perhaps try BeeCraft to get an insight into our weird square National hives with no mention anywhere of slatted racks. A digital subscription costs £25 (~$31.60) a year.

Dear Santa

I’ve been a good beekeeper and I’d like a DANA api MATIC1000 filling station with a 70 cm turntable from Swienty

Please 🙂

{{1}}: Literally ‘nonsense, gibberish, specialised to the point of being unintelligible to the general public’.

{{2}}: A phrase that has everything to do with the production of pig iron, and nothing to do with the production of bacon.

{{3}}: There is no ‘best’ smoker fuel.

{{4}}: I’ve got a post in draft about why honey forms long drippy ‘strands’.

{{5}}: From £3000 … and it’s been on my Christmas list for years.

{{6}}: Unless stated, prices quoted are the RRP for hardbacks.

{{7}}: Wild? They’re livid.

{{8}}: Recommended back in 2016 as well …

Join the discussion ...