Brood in all stages

Synopsis : The presence of brood in all stages (of development) is an important indicator of the state of your colony. Is it queenright? Is it expanding or contracting? Quantifying the various developmental stages – eggs, larvae and pupae – is not necessary, but being able to determine changes in their proportions is very useful.

Introduction

There’s something very reassuring about the words ’brood in all stages’ to a beekeeper, or at least to this beekeeper.

It means, literally, that there is brood in all stages of development i.e. eggs, larvae and pupae.

Update the notes …

As far as I’m concerned, it’s such an important feature of the hive that it gets its own column in my hive records, though the column heading is conveniently abbreviated to BIAS.

And BIAS is what I’ll mostly use for the remainder of this post, again for convenience.

Why is it so important?

Why, when you conduct an inspection of the colony, is the presence of BIAS so important?

And why should you be reassured if it is present?

Broadly I think there are two reasons:

- it tells you the likely queenright status of the hive. Is there a laying queen present?

- (with a little more work) you can determine the egg laying rate of the queen and whether it’s changing. This is important as it provides information of the likely adult worker strength of the colony in a few weeks’ time. Are there going to be enough bees to exploit the expected nectar flow? Will there be sufficient young bees for queen rearing?

Of course, detailed scrutiny of the eggs, larvae or pupae in the hive can provide a wealth of information about the health of the colony. I will mention one specific example later, but it’s not the main focus of this post.

The development cycle of the honey bee

The post last week emphasised the variation – from year to year – in the climate {{1}}. In contrast, despite the temperature fluctuating outside the hive, the environment inside the hive is remarkably stable. Partly as a consequence of this the development of the brood is very predictable.

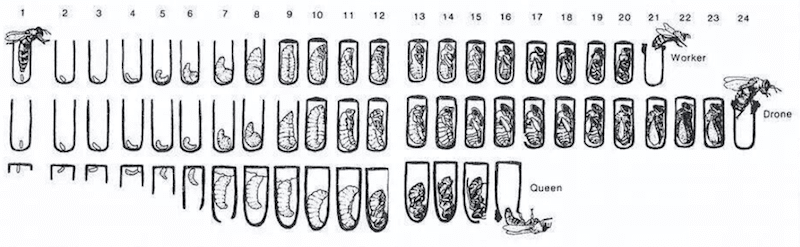

Honey bee development

Worker bees take 21 days to develop, by which I mean that an egg laid on day 1 will – assuming development is successful – result in an adult worker emerging {{2}} on day 21. There can be a few hours variation, largely influenced by temperature, but as far as we need to be concerned here worker bee development takes 21 days.

Days 1 to 3 are spent as an egg. The egg then hatches to release a larva which is fed for a little over five days before capping. The developing bee then pupates for about 13 days before emergence.

For simplicity it helps to think of the development cycle as 3 days as an egg, 5 days as a larva and 13 days as a pupa. EEELLLLLPPPPPPPPPPPPP {{3}} or 3:5:13 … I’ll return to these numbers later.

In fact it’s a little more complicated than that. The larva actually pupates after the cell is capped, so it exists in two states; an open larval stage during which is is fed by nurse bees and a capped larval stage which is more correctly termed the pre-pupal stage. The larva then metamorphoses into a pupa within the capped cell.

None of this really matters as far as your interpretation of the ’brood in all stages’ you see in the colony during a regular inspection. However, it’s reassuring to know that there’s lots of complicated things with weird names and confusing terminology going on in there … which I’ve simplistically distilled to 3:5:13.

But, if you do want to know more you could have a read of this article by Rusty Burlew which also appeared in the American Bee Journal 160:509-511 (2020).

Queenright or not?

So, if there are eggs present there must be a queen present, right?

Wrong 🙁

But it is more than likely 🙂

In fact, if there are eggs, larvae and sealed brood present i.e. BIAS, then you can be pretty confident there is a queen present.

Or, more correctly, that there was a queen present within the last 3 days.

If an egg takes three days to hatch then it is possible that the queen laid the eggs and has subsequently disappeared.

For example, the colony may have swarmed in the intervening period.

Alternatively, during that ’quick-but-entirely-unnecessary-peek’ you took inside the hive two days ago you inadvertently crushed the queen between the bars of a Hoffman frame.

Oops … eggs but no queen 🙁

Slim Jim Jane and pre-swarming egg laying activity

When a colony swarms the mated, laying queen leaves with the swarm. To ensure that she can fly sufficiently well she is slimmed down in the days before swarming and her egg laying rate slows significantly.

Despite searching – both the literature and my own memory banks {{4}} – I’ve failed to find any detailed information on how long before swarming her laying rate slows. It appears as though she generally does not stop laying before swarming, but it’s down to just a trickle (if that’s the right word) in comparison to when she’s ‘firing on all cylinders’.

Queen cells and laying workers

The other telltale sign that a swarmed colony leaves is the presence of one or (usually) more queen cells. Typically some of these are capped, with the colony swarming on the first suitable day after the first cell is capped.

Queen cells – good and bad

So, back to your colony that may or may not be queenright … the presence of only a small number of eggs compared to capped brood levels and one or more queen cells suggests that they have swarmed within the last 3 days.

In contrast, If there are ‘normal looking’ eggs present, even if few in number, and you didn’t have a ’quick-but-entirely-unnecessary-and-actually-a-bit-clumsy-peek’ two days ago, it’s likely that your colony is queenright.

I prefixed eggs (above) with ‘normal looking’ because there is one further situation when the colony has no queen but there are eggs present. That’s when the colony has developed laying workers.

Under certain conditions unmated worker bees can lay unfertilised eggs.

However, in contrast to the queen, workers have short, dumpy abdomens and cannot judge whether the cell already contains an egg. As a consequence they lay multiple eggs in cells and many of these eggs are in unusual positions – rather than being central at the bottom of the cell they are on the sidewalls, or the sloping edges of the base of the cell.

Multiple eggs per cell = laying workers (usually)

These eggs are usually laid in worker cells. Being unfertilised they can only develop into drones, and since they are in cells that are too small for drones they end up protruding like little bullets from the comb.

Laying workers …

They are also scattered randomly around the frame, rather than being in the concentric ring pattern used when the queen lays up a frame.

BIAS and the queenright status of the colony

So, let’s summarise that lot before (finally) getting back to 3:5:13.

If:

- there is BIAS and no queen cells present and you’ve not disturbed the colony in the last few days … then the colony is most likely queenright. Yes, there’s an outside chance she recently dropped dead, but it’s much more likely that you just can’t find her. Don’t worry, the presence of BIAS and the other supporting signs tell you all you need to know … there’s a queen present and she’s laying. All is good with the world. Be reassured 🙂

- there is BIAS and capped queen cells … then it’s likely they swarmed very recently 🙁

- eggs are present, possibly together with some small, unsealed queen cells and you had a ’quick-but-entirely-unnecessary-and-frankly-a-bit-stupid-in-retrospect-peek’ two days ago … then all bets are off. The colony may or may not be queenright. Only inspect when you need to and be very careful returning frames to the hive {{5}}. If you didn’t open the hive in the last few days (and accidentally obliterate the queen) the presence of BIAS and unsealed queen cells usually means that the colony is queenright but is preparing to swarm. Swarm control is urgently needed.

- multiple eggs are present in strange places in cells, coupled with scattered bullet-shaped capped cells (and oversized larvae in worker cells) … then there are laying workers present. Your colony is not queenright. Technically I suppose there is brood in all stages, but the brood looks odd. But there’s somethings else as well … laying workers develop in the absence of pheromones produced by open brood (larvae). Therefore to develop laying workers a colony transitions through a period when there is not brood in all stages. In my experience laying workers usually develop after a colony experiences a protracted period when it is totally broodless i.e. no eggs, larvae or pupae.

Let’s move on.

3:5:13

If the queen is laying at a steady rate i.e. the same number of eggs per day, then the ratio of eggs to larvae to sealed brood will be about 3:5:13.

This means for every egg present you should expect to find just less than two larvae and slightly more than four capped worker cells.

I’m not suggesting you count them, but you should be able to judge the approximate proportions of the three brood types during your inspections.

This is more complicated than it sounds (and it already sounds quite complicated). The queen lays eggs in an expanding 3D rugby-ball shaped space – the ellipsoid broodnest – moving from frame to frame. Consequently, individual frames will contain different proportions of eggs, larvae and capped pupae, but the overall proportions should work out to be about 3:5:13.

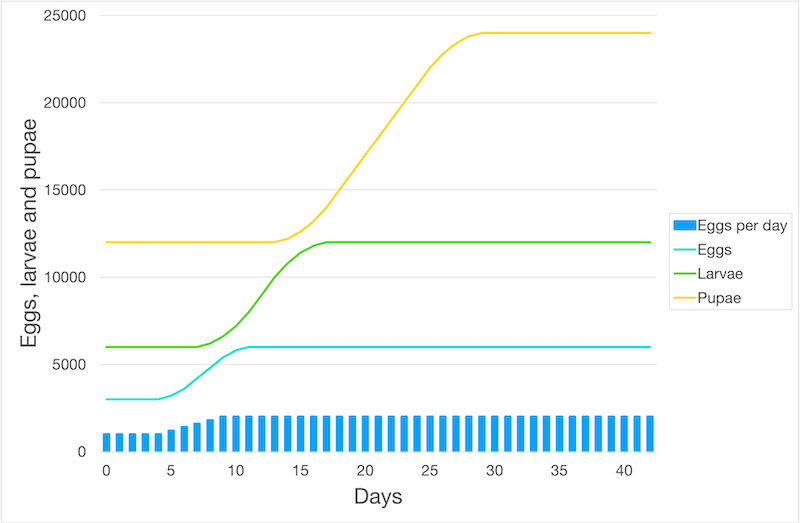

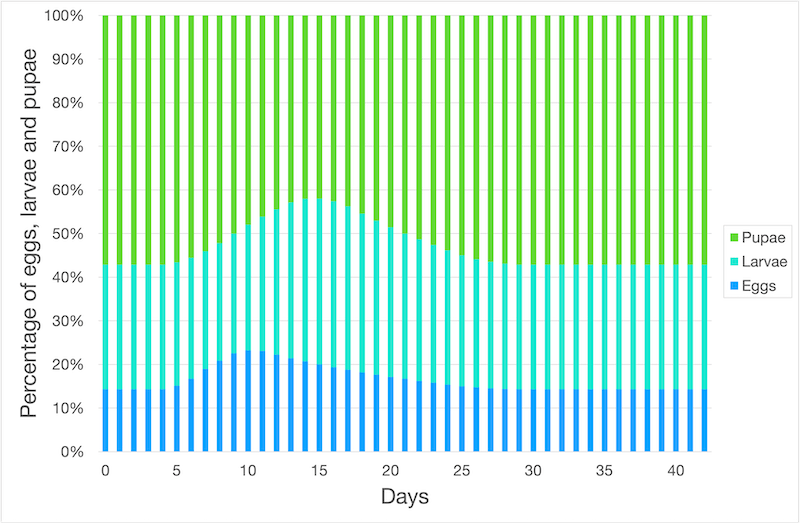

And this is where things start to get a little more interesting {{6}}.

A picture is worth a thousand words

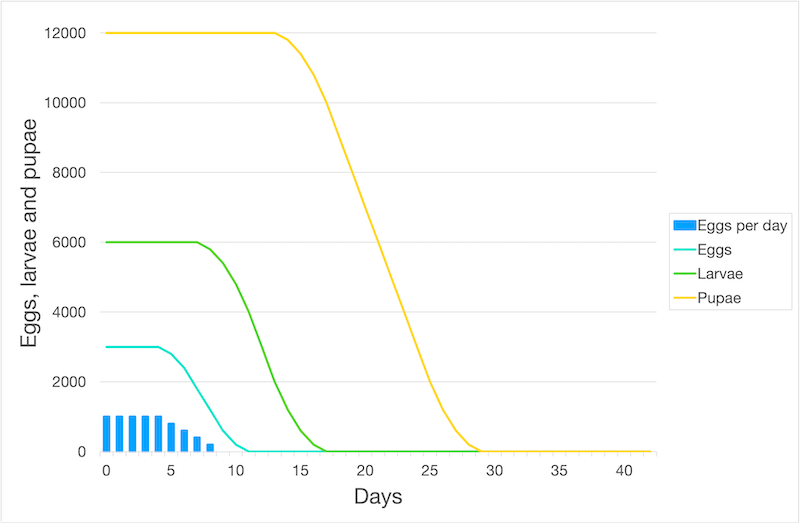

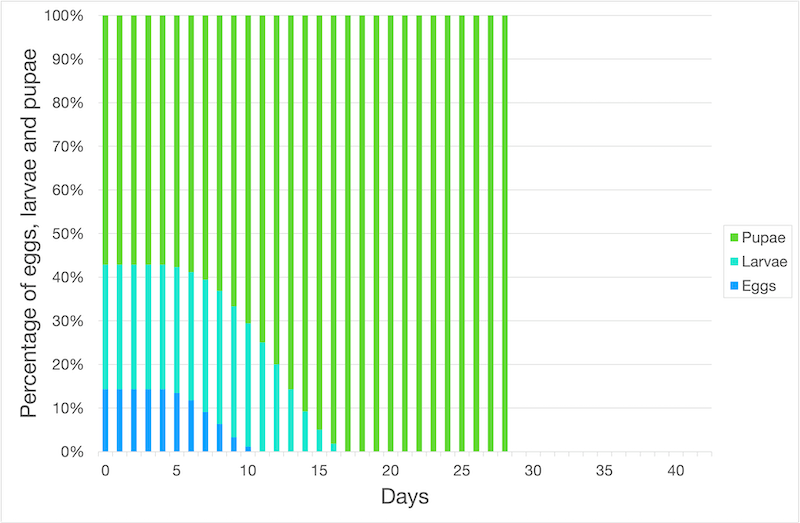

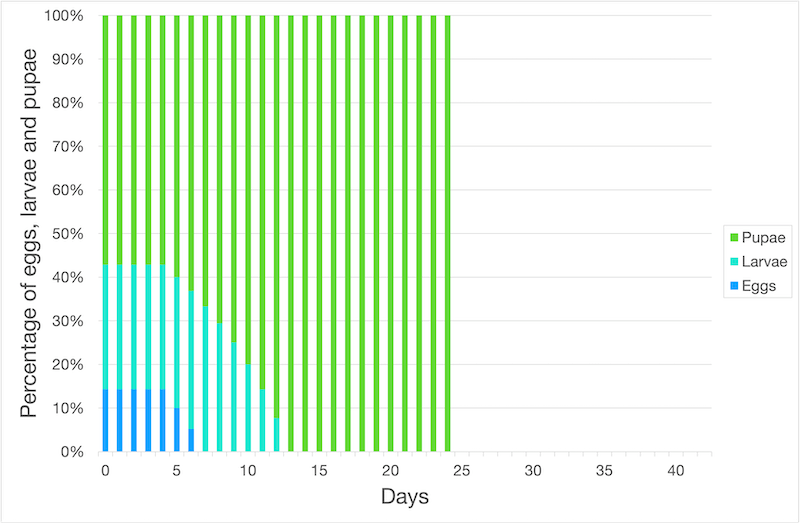

I’ve drawn some simple Excel charts to illustrate some of the points I want to make. For each of the charts I’ve assumed the queen lays at 1000 eggs per day for the first 5 days and then she either stops altogether (perhaps one of those ’quick-but-entirely-unnecessary-and-frankly-idiotic-peek’ queen-meets-Hoffman-frame scenarios), or either speeds up or slows down her laying rate by 200 eggs per day.

The numbers don’t matter, just focus on the proportions of different classes of brood.

Speeding up

If there are more eggs and larvae expected – when compared to the levels of capped brood – then the laying rate of the queen is increasing. For example, here is what happens when she increases her laying rate from 1000 to 2000 eggs/day over 5 days.

Queen increasing her laying rate

The line graph is perhaps less clear than a simple plot of the percentages of the three types of brood. Note the relative reduction in capped brood (pupae) around day 15.

Changes in percentages of brood as queen increases her laying rate

If this occurs it means that the colony has the resources – pollen and nectar – to expand and that you’ll have more young adult workers in another fortnight or so, and an increased foraging force in 4-5 weeks. These things are important if you are thinking about the ability to exploit a summer nectar flow, or perhaps to rear queens in the colony.

Slowing down

Conversely, if eggs and larvae are much less than about 40% of the total brood {{7}}, then the queen is reducing her laying rate. Perhaps there is a dearth of nectar or pollen? Does the colony have sufficient stores? Do you need to feed – little and often – some thin syrup to stimulate brood rearing?

Queen slowing her laying rate (e.g. prior to swarming)

Or is the colony slimming down the queen in preparation for swarming? Do they have sufficient space? Is the colony backfilling brood cells with nectar?

Changes in percentage of brood as the queen slows her laying rate (e.g. prior to swarming)

Note how 12 days after the Q slows her laying rate (assuming she stops entirely {{8}} ) then the only things left in the colony is sealed brood.

Queen-meets-Hoffman-frame scenario

This is essentially the same as slowing down, except it all happens more abruptly.

Disappearance of brood after the queen abruptly disappears

If you inadvertently kill the queen the colony very quickly runs out of eggs and larvae. Using the emergency response you would expect the colony to raise queen cells promptly.

Estimating brood area during inspections

I’m not suggesting you count eggs, larvae or sealed brood. Inspections are best when they are relatively non-intrusive. It disturbs the colony, it can agitate the bees and it changes the pheromone concentrations and distribution which control so much of what happens in the hive.

But it is worth learning how to determine whether there is more or less sealed brood than open brood and eggs.

Scientists have developed a number of ways to accurately quantify colony strength and population dynamics.

The classic approach, developed between the 1960’s and 1980’s is termed the Liebefeld Method and was nicely reviewed by Ben Dainat and colleagues in a recent paper in Apidologie {{9}}. More recent strategies include the use of digital photography and image analysis, either using ImageJ or semi-automated python scripts such as CombCount.

But none of those approaches are really practical during a normal colony inspection.

I guesstimate the relative proportions of eggs + larvae and sealed brood, and also try and work out the approximate total levels of BIAS present in the colony.

If about 60% of the brood is sealed and there are 3 full frames and about 6 half frames of brood in all stages I would be happy that the colony was queenright, that the laying rate of the queen was probably stable and I’d record the total levels of BIAS as 6 (full frames in total).

Eyeballing sealed brood levels

When you get a frame like the one below it’s easy to work out how much brood it contains.

That’ll do nicely …

It’s as near as makes no difference one full frame (assuming the other side looks similar).

But most frames contain a more or less oval brood pattern, some of which may have already emerged.

Brood frame

In these instances it helps to guesstimate what halves, quarters, eighths look like. Or use the diagrams of brood patches on Dave Cushman’s site to work out the approximate total levels.

It’s also worth remembering that the presence of adult bees on the frames will confound things.

Lots of capped brood … somewhere under all those bees

To properly judges the levels of brood you need to shake the bees off the frames. This adds even more disruption to the inspection and I only ever really do it in two specific situations:

- when looking for signs of brood disease, such as foulbrood

- when I have to find every single queen cell in the colony

During normal inspections I work with what I can see … and if I need to see more (eggs, larvae or sealed brood) I gently run the back of my hand over the attached workers, or blow gently on them. Both these methods encourages them to move aside, without the ignominy of being dumped in a writhing heap at the bottom of the brood box.

In conclusion

As described – other than the Liebefeld Method – estimating the amount of brood in all stages (BIAS) is a rather inexact process. However, despite this, it’s a useful exercise that helps you judge the state of the colony, and gives you some insight into what is likely to happen over the next few weeks.

And, let’s face it, anything that gives us a better idea of what to expect is useful 😉

Note

Eagle eyed readers will realise there’s a slight glitch in the numbers graphed above. I realised this as silly o’clock {{10}} this morning and haven’t had time to go back and butcher the spreadsheet and redraw all the graphs. My error does not fundamentally change the patterns observed, but just alters the percentages slightly. I’ll update them once I’ve had a nap 😉

{{1}}: Since then, as predicted, the cuckoos have arrived – on the 26th. This was 8 days later than 2020 (a notably warm spring).

{{2}}: Not hatching, that’s what eggs do.

{{3}}: Like the noise you make when you put your ungloved hand into your beesuit pocket and discover an aggrieved bee.

{{4}}: Only about 16k of RAM these days.

{{5}}: And don’t ask me how I’m so horribly familiar with this situation.

{{6}}: Yes … really!

{{7}}: 3+5/21 x 100

{{8}}: Or near as makes no difference.

{{9}}: Dainat, B., Dietemann, V., Imdorf, A. et al. A scientific note on the ‘Liebefeld Method’ to estimate honey bee colony strength: its history, use, and translation. Apidologie 51, 422–427 (2020).

{{10}}: Which is about an hour after 1 am.

Join the discussion ...