Brexit and beekeeping

The ‘oven ready’ deal the government struck with the EU in the dying hours of 2020 was a bit less à la carte and a bit more table d’hôte.

The worst of the predictions of empty supermarket shelves and the conversion of Essex into a 3500 km2 lorry park have not materialised {{1}}.

But there are other things that haven’t or won’t appear.

And one of those things is bees.

Bee imports

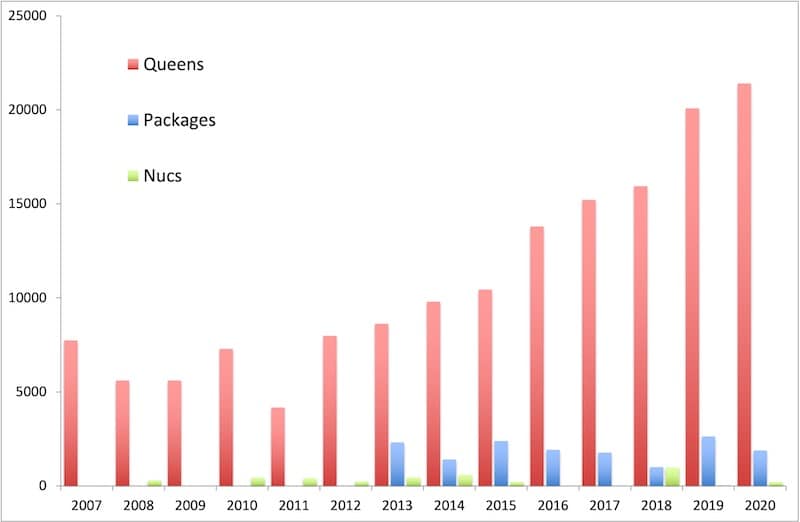

There is a long history of bee imports into the UK, dating back at least a century. In recent years the number of imports has markedly increased, at least partially reflecting the increasing popularity of beekeeping.

Queens are imported in cages, usually with a few attendant workers to keep them company. Nucs are small sized colonies, containing a queen, bees and brood on frames.

Packages are the ‘new kid on the block’ (in the UK) with up to 2500 per year being imported after 2013. Packages are queenless boxes of bees, containing no frames or brood.

They are usually supplied in a mesh-sided box together with a queen. The bees are placed into a hive with frames of foundation and the queen is added in an introduction cage. They are fed with a gallon to two of syrup to encourage them to draw comb.

It’s a very convenient way to purchase bees and avoids at least some of the risk of importing diseases {{2}}. It’s also less expensive. This presumably reflects both the absence of frame/foundation and the need for a box to contain the frames.

But, post-Brexit, importation of packages or nucs from EU countries is no longer allowed. You are also not allowed to import full colonies (small numbers of these were imported each year, but insufficient to justify adding them to the graph above).

Queen imports are still allowed.

Why are were so many bees imported?

The simple answer is ‘demand’.

Bees can be reared inexpensively in warmer climates, such as southern Italy or Greece. The earlier start to the season in these regions means that queens, nucs or packages can be ready in March to meet the early season demand by UK beekeepers.

If you want a nuc with a laying queen in March or April in the UK you have two choices; a) buy imported bees, or b) prepare or purchase an overwintered nuc.

I don’t have data for the month by month breakdown of queen imports. I suspect many of these are also to meet the early season demand, either by adding them to an imported package (see above) or for adding to workers/brood reared and overwintered in a UK hive that’s split early in the season to create nucleus colonies.

Some importers would sell the latter on as ‘locally reared bees’. They are … sort of. Except for the queen who of course determines the properties of all the bees in the subsequent brood 🙁

An example of being “economical with the truth” perhaps?

Imported queens were also available throughout the season to replace those lost for any number of reasons (swarming, poor mating, failed supersedure, DLQ’s, or – my speciality – ham-fisted beekeeping) or to make increase.

And to put these imports into numerical context … there are about 45,000 ‘hobby’ beekeepers in the UK and perhaps 200+ bee farmers. Of the ~250,000 hives in the UK, about 40,000 are managed by bee farmers.

What are the likely consequences of the import ban?

I think there are likely to be at least four consequences from the ban on the importation of nucs and packages to the UK from the EU:

- Early season nucs (whatever the source) will be more expensive than in previous years. At the very least there will be a shortfall of ~2000 nucs or packages. Assuming demand remains the same – and there seems no reason that it won’t, and a realistic chance that it will actually increase – then this will push up the price of overwintered nucs, and the price of nucs assembled from an imported queen and some ‘local’ bees. I’ve seen lots of nucs offered in the £250-300 range already this year.

- An increase in imports from New Zealand. KBS (and perhaps others) have imported New Zealand queens for several years. If economically viable this trade could increase {{3}}.

- Some importers may try and bypass the ban by importing to Northern Ireland, ‘staging’ the bees there and then importing them onwards to the UK. The legality of this appears dubious, though the fact it was being considered reflects that this part of the ‘oven ready’ Brexit deal was not even table d’hôte and more like good old-fashioned fudge.

- Potentially, a post-Covid increase in bee smuggling. This has probably always gone on in a limited way. Presumably, with contacts in France or Italy, it would be easy enough to smuggle across a couple of nucs in the boot of the car. However, with increased border checks and potential delays, I (thankfully) don’t see a way that this could be economically viable on a large scale.

Is that all?

There may be other consequences, but those are the ones that first came to mind.

Of the four, I expect #1 is a nailed-on certainty, #2 is a possibility, #3 is an outside possibility but is already banned under the terms of the Northern Ireland Protocol which specifically prohibits using Northern Ireland as a backdoor from Europe, and #4 happens and will continue, but is small-scale.

Of course, some, all or none of this ban may be revised as the EU and UK continue to wrangle over the details of the post-Withdrawal Agreement. Even as I write this the UK has extended the grace period for Irish sea border checks (or ‘broken international law’ according to the EU).

This website is supposed to be a politics-free zone {{4}} … so let’s get back to safer territory.

Why is early season demand so high?

It seems likely that there are three reasons for this early season demand:

- Commercial beekeepers needing to increase colony numbers to provide pollination services or for honey production. Despite commercials comprising only ~0.4% of UK beekeepers, they manage ~16% of UK hives. On average a commercial operation runs 200 hives in comparison to less than 5 for hobby beekeepers. For some, their business model may have relied upon the (relatively) inexpensive supply of early-season bees.

- Replacing winter losses by either commercial or amateur beekeepers. The three hives you had in the autumn have been slashed to one, through poor Varroa management, lousy queen mating or a flood of biblical proportions. With just one remaining hive you need lots of things to go right to repopulate your apiary. Or you could just buy them in.

- New beekeepers, desperate to start beekeeping after attending training courses through the long, dark, cold, wet winter. And who can blame them?

For the rest of the post I’m going to focus on amateur or hobby beekeeping. I don’t know enough about how commercial operations work. Whilst I have considerable sympathy if this change in the law prevents bee farmers fulfilling pollination or honey production contracts, I also question how sensible it is to depend upon imports as the UK extricates itself from the European Union.

Whatever arrangement we finally reached it was always going to be somewhere in between the Armageddon predicted by ‘Project Fear’ and the ‘Unicorns and sunlit uplands’ promised by the Brexiteers.

And that had been obvious for years.

I have less sympathy for those who sell on imported bees to meet demand from existing or new beekeepers. This is because I think beekeeping (at least at the hobbyist level) can, and should, be sustainable.

Sustainable beekeeping

I would define sustainable beekeeping as the self-sufficiency that is achieved by:

- Managing your stocks in a way to minimise winter losses

- Rearing queens during the season to requeen your own colonies when needed (because colonies with young queens produce brood later into the autumn, so maximising winter bee production) and to …

- Overwinter nucleus colonies to make up for any winter losses, or for sale in the following spring

All of these things make sound economic sense.

More importantly, I think achieving this level of self-sufficiency involves learning a few basic skills as a beekeeper that not only improve your beekeeping but are also interesting and enjoyable.

I’ve previously discussed the Goldilocks Principle and beekeeping, the optimum number of colonies to keep considering your interest and enthusiasm for bees and the time you have available for your beekeeping.

It’s somewhere between 2 and a very large number.

For me, it’s a dozen or so, though for years I’ve run up to double that number for our research, and for spares, and because I’ve reached the point where it’s easy to generate more colonies (and because I’m a lousy judge of the limited time I have available 🙁 ).

Two is better than one, because one colony can dwindle, can misbehave or can go awry, and without a colony to compare it with you might be none the wiser that nothing is wrong. Two colonies also means you can always use larvae from one to rescue the other if it goes queenless.

And with just two colonies you can easily practise sustainable beekeeping. You are no longer dependent on an importer having a £30 mass-produced queen spare.

What’s wrong with imported bees?

The usual reason given by beekeepers opposed to imports is the risk of also importing pathogens.

Varroa is cited as an example of what has happened.

Tropilaelaps or small hive beetle are given as reasons for what might happen.

And then there are usually some vague statements about ‘viruses’.

There’s good scientific evidence that the current global distribution of DWV is a result of beekeepers moving colonies about.

More recently, we have collaborated on a study that has demonstrated an association between honey bee queen imports and outbreaks of chronic bee paralysis virus (CBPV). An important point to emphasise here is that the direction of CBPV transmission is not yet clear from our studies. The imported queens might be bringing CBPV in with them. Alternatively, the ‘clean’ imported queens (and their progeny) may be very susceptible to CBPV circulating in ‘dirty’ UK bees. Time will tell.

However, whilst the international trade in plants and animals has regularly, albeit inadvertently, introduced devastating diseases e.g. Hymenoscyphus fraxineus (ash dieback), I think there are two even more compelling reasons why importation of bees is detrimental.

- Local bees are better adapted to the environment in which they were reared and consequently have increased overwintering success rates.

- I believe that inexpensive imported bees are detrimental to the quality of UK beekeeping.

I’ve discussed both these topics previously. However, I intend to return to them again this year. This is partly because in this brave new post-Brexit world we now inhabit the landscape has changed.

At least some imports are no longer allowed. The price of nucs will increase. Some/many of these available early in the season will be thrown together from overwintered UK colonies and an imported queen.

These are not local bees and they will not provide the benefits that local bees should bring.

Bad beekeeping and bee imports

If imported queens cost £500 each {{5}} there would be hundreds of reasons to learn how to rear your own queens.

But most beekeepers don’t …

Although many beekeepers practise ‘passive’ queen rearing e.g. during swarm control, it offers little flexibility or opportunity to rear queens outside the normal swarming season, or to improve your stocks.

In contrast, ‘active’ queen rearing i.e. selection of the best colonies to rear several queens from, is probably practised by less than 20% of beekeepers.

This does not need to involve grafting, instrumental insemination or rows of brightly coloured mini-nucs. It does not need any large financial outlay, or huge numbers of colonies to start with.

But it does need attention to detail, an understanding of – or a willingness to learn – the development cycle of queens, and an ability to judge the qualities of your bees.

Essentially what it involves is slightly better beekeeping.

But, the availability of Italian, Greek or Maltese queens for £20 each acts as a disincentive.

Why learn all that difficult ‘stuff’ if you can simply enter your credit card details and wait for the postie?

And similar arguments apply to overwintering nucleus colonies. This requires careful judgement of colony strength through late summer, and the weight of the nuc over the winter.

It’s not rocket science or brain surgery or Fermat’s Last Theorem … but it does require a little application and attention.

But, why bother if you can simply wield your “flexible friend” {{6}} in March and replace any lost colonies with imported packages for £125 each?

Rant over

Actually, it wasn’t really a rant.

My own beekeeping has been sustainable for a decade. I’ve bought in queens or nucs of dark native or near-native bees from specialist UK breeders a few times. I have used these to improve my stocks and sold or gifted spare/excess nucs to beginners.

I’ve caught a lot of swarms in bait hives and used the best to improve my bees, and the remainder to strengthen other colonies.

The photographs of packages (above) are of colonies we have used for relatively short-term scientific research.

I’m going to be doing a lot of queen rearing this season. Assuming that goes well, I then expect to overwinter more nucs than usual next winter.

I then hope that the bee import ban remains in place for long enough until I can sell all these nucs for an obscene profit which I will use to purchase a queen rearing operation in Malta. 😉

And I’m going to write about it here.

Notes

BBKA statement made a day or two after this post appeared. The BBKA and other national associations are concerned about the potential import of Small Hive Beetle (SHB) into the UK via Northern Ireland. Whilst I still think this breaches the Northern Ireland Protocol, it doesn’t mean it won’t be attempted (and there’s at least one importer offering bees via this route). It’s not clear that the NI authorities have the manpower to inspect thousands of packages.

It’s worth noting that SHB was introduced to southern Italy in 2014 and remains established there. The most recent epidemiological report shows that it was detected as late as October 2020 in sentinel apiaries and is also established in natural colonies.

With a single exception – see below – every country into which SHB has been imported has failed to eradicate it. As I wrote in November 2014:

“Once here it is unlikely that we will be able to eradicate SHB. The USA failed, Hawaii failed, Australia failed, Canada failed and it looks almost certain that Italy has failed.”

And Italy has failed.

The one exception was a single import to a single apiary in the Portugal. Notably, the illegal import was of queens, not nucs or packages. Eradication involved the destruction of the colonies, the ploughing up of the apiary and the entire area being drenched in insecticide.

The Beekeepers Quarterly

This post also appeared in the summer 2021 edition of The Beekeepers Quarterly published by Northern Bee Books.

{{1}}: Though there are shortages as anyone who has tried to purchase things from Europe will know … the honey creamer I posted about a fortnight ago is not currently available directly as it was in December when I bought mine.

{{2}}: Though it certainly does not negate the risk completely.

{{3}}: Importing packages from New Zealand is still allowed, but is likely to be expensive.

{{4}}: And any comments ranting on about the pros or cons of Brexit will be binned I’m afraid … it’s my site and I have full, and sole, editorial control.

{{5}}: Some do … but these are breeder queens and not the sort ‘piled high and sold cheap’ to most amateur beekeepers.

{{6}}: Remember that? … Access credit card advertising from 1979.

Join the discussion ...