Beekeeping in winter

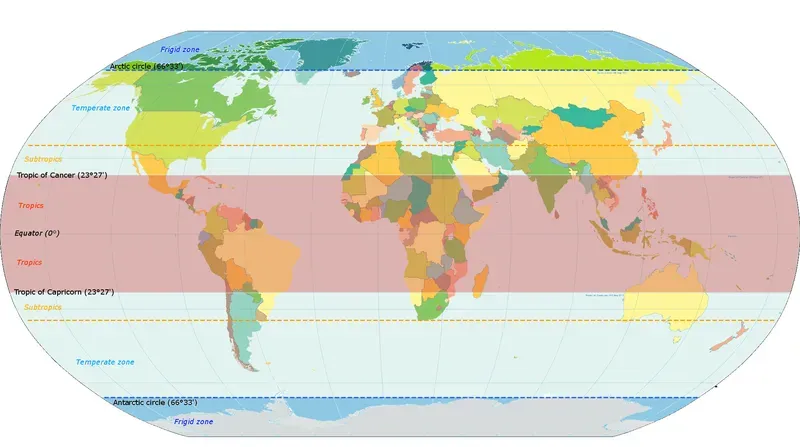

If you keep bees in temperate latitudes your beekeeping year is more or less seasonal, depending on how far from the equator you are.

The spring and summer are busy, with colony expansion, swarm control, queen rearing and honey production. The further north (or south) you are, the shorter the period all these activities are shoehorned into.

When I lived in the English Midlands I'd start queen rearing in late April, and - in a good season - finish in early September. Now I live in Scotland I'm usually restricted to mid/late May to late July for my queen rearing. On the West Coast of Scotland the season starts even later, and I sometimes complete only a single round of queen rearing before the early autumn low pressure systems roll in from the Atlantic, terminating any chance of queen mating and simultaneously ruining the heather harvest 😢.

To take proper advantage of this short beekeeping season requires preparation.

Autumn, whether it arrives in early August or late September, can also be busy ... there's uniting to do, Varroa control to apply and colonies to be fed. In some ways, these are the most important events in the year, and some are time-critical. Applied too late and the colonies have less chance of overwintering successfully. However, although important, they only involve a few visits to the apiary, so they are hardly onerous.

But then what?

With a couple of notable exceptions, I usually don't open a hive between August and the following April. That's almost two-thirds of the beekeeping year in which I do no practical beekeeping.

But that doesn't mean that there aren't things to do.

Retail

Honey sales are a year-round activity, but - at least in the stores I supply - there's an uptick in sales in late summer, coinciding with the availability of the summer honey, and always in the run-up to Christmas.

Therefore, although the beekeeping season is effectively over, I'm still busy filtering, jarring and labelling honey, searching around for boxes strong enough to pack/carry it in, and delivering it to the stores.

For whatever reason, the clear/runny summer honey I produce is more popular than the soft set. I think some consumers only consider 'honey' if it's runny, so missing out on some of the wonderful heather-blended soft set ... ho hum, their loss.

So, if you sell honey, it's worth checking whether you have sufficient jars and labels for the sales you hope to achieve. There are few things more frustrating than getting a large order {{1}} and finding your supplier has the jars you prefer on back order.

Yes, you could change the jar shape or size, but that means regular customers might not recognise it on the shelves, and may well mean you need to get new labels printed.

For years now I've standardised on square jars with black lids. They look smart and distinctive in the store, and are easy to stack/pack. The flat face also makes it relatively easy to (manually {{2}}) get the label aligned, so they look good in a row on the shelf. Locally, I'm the only one using these jars, so regular purchasers can easily find them.

Reviewing the season

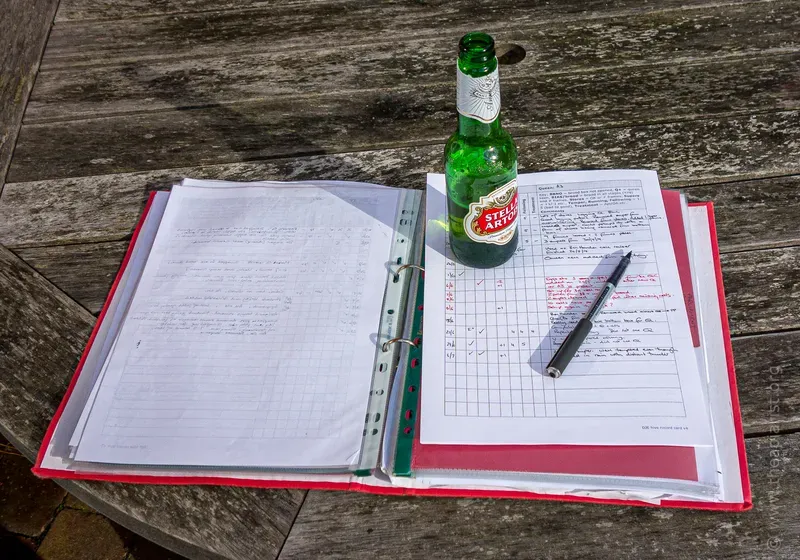

Regular readers will, of course, take exemplary notes during or after hive inspections. They'll know the ages of the queens, the dates they emerged on, whether they were supersedure, grafted or reared in the hive during swarm control.

They'll know the yield of honey per hive, perhaps for multiple harvests, so will know which are the most productive colonies, and which 'could do better'.

If they are especially swotty, they will also have records of which colonies were most frugal last winter, together with a host of other notes on their stability on the comb, pathogen resistance (phoretic Varroa counts each month perhaps?), temper in good weather and bad, brood pattern, swarminess etc.

Or, perhaps not.

I'm well aware of the importance of keeping good hive records. They are essential for 'strategic' planning; which colonies to rear queen from, which need requeening etc. However, my notes only cover a fraction of the stuff listed in the first three paragraphs of this section.

But, in most seasons I still remember a little bit more than is written down in the notes.

Which is where the reviewing becomes important.

Reminders for the season ahead

Before some of the key facts or observations are overwritten by my increasingly selective and untrustworthy memory, I try and look through my hive notes and produce a one line summary of the season for each colony:

"Swarmy, poor brood pattern, high mites, below-average honey."

Or, hopefully something more like:

"22 Q (still), great laying pattern, low mites, high honey, use for QR next year."

It's only after I've harvested the summer honey that I know which colonies performed best, and that seems like a logical end point at which to summarise things. By thinking through the season on a per colony basis I sometimes remember additional things that get woven into the summary.

One sentence is a bit more informative than a one-word OFSTED judgement, and it saves re-reading the notes completely to check whether the colony got really aggressive in bad weather, or swarmed early and often, or whatever ... and, if your notes are handwritten, that one sentence might even be legible 😉.

I'm certain there are more thorough ways to do this, but it's a useful way to spend an evening (accompanied by a glass of Merlot) and will bring back many happy memories of the season just finished.

Although it might be tempting fate (some colonies could still be lost overwinter), the 'single sentence summary' is a good thing to add to the top of the relevant hive record sheet for next season {{3}}.

Revision

Beekeepers interested in the theory and practice of beekeeping - at least the theory and practice according to those who set and assess the exams - might be taking exam modules this winter. That being the case, with no more pesky colony inspections to undertake, they can concentrate on learning how many Malpighian tubules {{4}} a larva has, or the number of emergency cells produced when the queen is removed, or the names of the hive designs that use top bee space.

Whilst I'm sure some of this information is important, interesting or relevant, exams really do not "float my boat". I was bad at them when I really needed to be better, became better at them before it was too late, and then - during my career - taught, set and marked countless more.

Perhaps understandably, I now have a deep-seated aversion to them. They can increase knowledge, but may not help understanding.

Does knowing the number of Malpighian tubules {{5}} improve your beekeeping?

Perhaps, though it's not clear (to me) how.

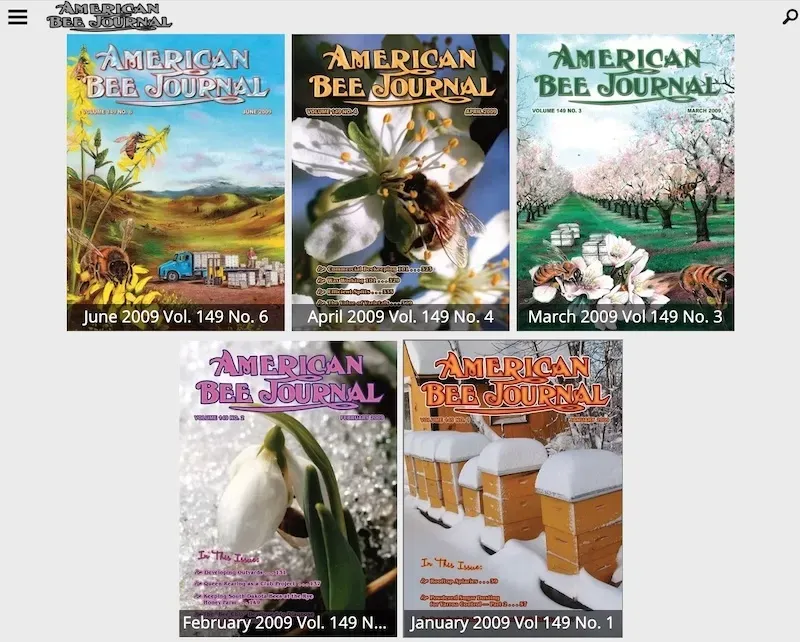

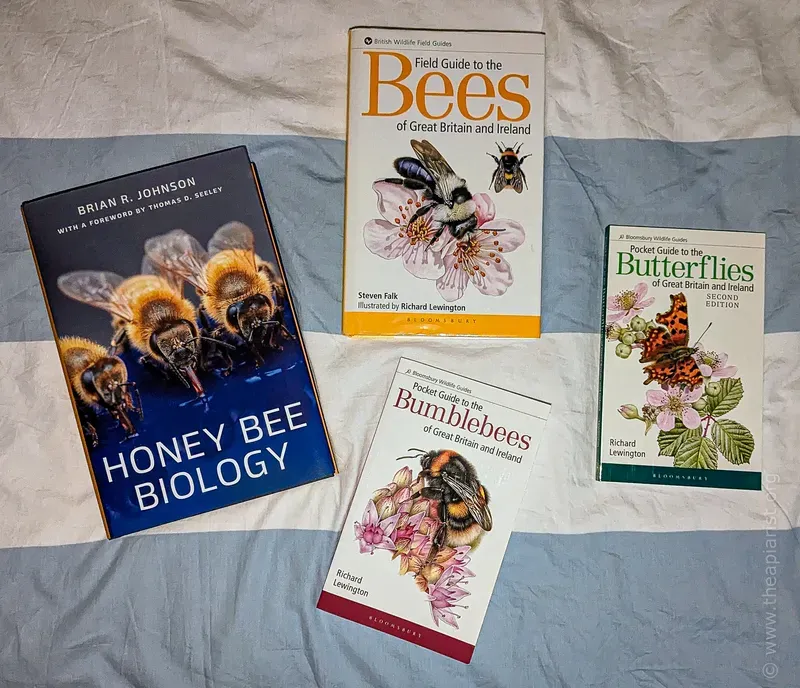

However, learning more about bees - and not just honey bees - and beekeeping, has undoubtedly helped my practical beekeeping. I've not got a certificate to show for it, but I've thoroughly enjoyed reading about the subjects that interest me, either in books, scientific papers, the beekeeping journals (particularly the American Bee Journal; ABJ), or talking to other beekeepers, those involved in bee health, or beekeeping administration.

Reading around the subject

Good luck if you are taking the modules this year or next, you've got a lot to revise. However, if you're not taking the modules {{6}} the winter is still a good time to read a bit around our fascinating subject.

Many of the early beekeeping books are available as reprints, and there are online repositories of beekeeping magazines from the late 19th Century, or - without a subscription - a digital archive of ABJ for all but the last 12 months.

The publications might be out of date, but the observations are not. What's more, beekeeping has not fundamentally changed since the development of the removable-frame hive (with the exception of the introduction of [insert name your least favourite pathogen here] {{7}}).

Alternatively, there are some excellent biographies of some important individuals in either beekeeping or bee biology, some good accessible science accounts of recent research, and any number of books on practical beekeeping.

Of these, I generally don't bother with the 'books on beekeeping' ... almost all seem to rehash similar material in one form or another. I'm certain this means I miss some great writing, some insightful new methods or some fantastic, time- or swarm-saving advances, but I'd prefer to read other stuff rather than skipping through yet another turgid account of the Pagden artificial swarm in search of those vanishingly rare insights or new methods.

The brave (or foolhardy) can tackle the current scientific literature. Lots of studies are now published in Open Access journals, or should be. Many of the better journals provide a summary for the layperson to accompany the gory details.

As our environment changes - with new pathogens and parasites, climate change etc. there will probably be significant repercussions for our beekeeping. Since honey bees are, rightly or wrongly, one of the best researched insects, many of these environmental studies focus on the consequences for, or the impact of, our bees.

There are now many - sometimes contradictory - studies but, over time, a pattern will emerge that will inform, and may well change, our beekeeping and the beekeepers of the future; at what density do hive numbers negatively influence wild bees? How will queen mating be affected by warmer, wetter summers? What will happen as flowering periods change? Will honey bee competition with other pollinators increase?

Read all about it!

Repair, renovation and replacement

Beekeeping equipment is designed to take the routine knocks and scrapes that occur during the course of the season. Furthermore, with almost no moving parts, and simple construction from wood or moulded polystyrene, there's almost nothing to go wrong with the majority of the kit we use.

It can be stacked up, strapped up and simply ignored.

Any drawn brood comb needs to be protected from the ravages of wax moths. Certan is no longer available, so wrapping the boxes tightly in pallet-wrap/clingfilm might be the best bet. Similarly, 'wet' supers should be stored in bee-tight stacks, to avoid unwanted attention from bees and wasps.

Spare floors need to be cleaned ready for the season ahead and brace comb and propolis should be removed from queen excluders once they are no longer in use (and, if you are leaving a super on the hive overwinter, do not leave a queen excluder on as well ... think about what happens to the queen once the majority of bees move up to access the stores).

At some point over the winter I'll go through my queen rearing kit, cleaning (a quick wash in very hot soapy water, followed by a thorough rinse is sufficient) or replacing my stocks of queen cups and holders. A comprehensive review and clearout of the bee bag will happen sometime in the depths of winter.

Repairs, although rarely needed, should be considered in the context of the cost and likely lifespan of the equipment. A warped or warping cedar super, which - infuriatingly {{8}} - no longer sits square on the box below, can be replaced for £15, will last for years, but might take ages to repair unsatisfactorily.

Regular replacements

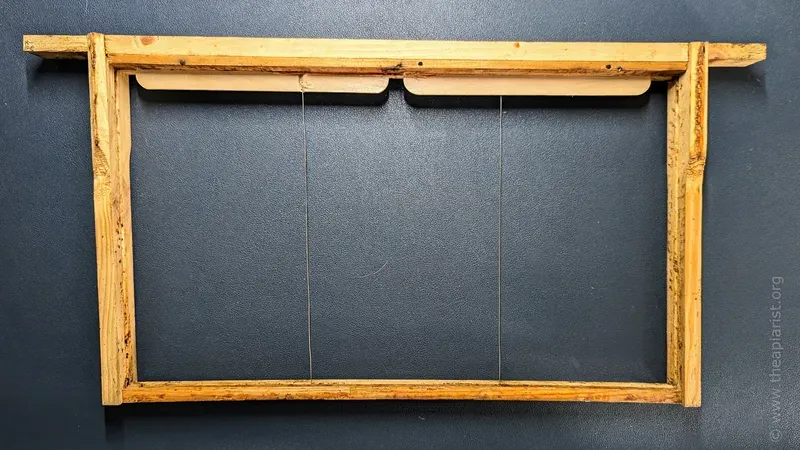

Frame building should be a winter activity, but I rarely get started - let alone finished - during the cold, dark winter months. It's a noisy business; with the incessant ker-chunk of the nail gun, or the regular hammering and intermittent swearing when I hit my thumb, so it really needs to be done outdoors. If the weather is cold, that's an unappealing prospect ... even more so when I think back to how painful a misplaced hammer blow is to a semi-frozen fingertip.

If you are more dedicated than me in your winter frame building (and it wouldn't be difficult) then don't be tempted to add the foundation until the weather warms. It's brittle at cold temperatures, and it just makes the frames even more difficult to store in volume.

Finally, if you are making frames, how about making some designed for use without foundation? Foundationless frames will save you £1.50 a frame in foundation costs, work fantastically well in bait hives, and - if used properly - are drawn out beautifully by the bees and end up as robust and long-lasting as frames built with foundation.

Relaxing

Beekeeping takes up a lot of my time, but I've got other activities and interests. Although a winter busman's holiday to see beekeeping friends and contacts in New Zealand is vaguely appealing, the travel definitely is not, so I indulge in some of these other interests - walking, cycling, photography etc. - close to home.

But I'll also be multitasking and using some of this relaxation during my preparations for the season ahead.

This winter, having moved to the Scottish Borders, I have to find some new apiary sites and familiarise myself with the local geography. The nearby hills (the Cheviots) are heavily grazed and appear to have little heather. The fields around the house are largely arable, so I'll be out and about on my bike scouting for the fields with oil seed rape to get the bees an early boost.

This part of Scotland is usually warmer and definitely drier than the West Coast {{9}}, and less subject to the regular chilly easterlies my bees in Fife 'enjoyed', so I'll have lots to learn about the environment and how the bees will cope with it.

And I'll be talking to the local beekeepers to find out as much as I can about the area before the season starts.

Which, in a rather contrived manner, brings me to ...

Repeating myself

I give a lot of talks to beekeeping associations over the winter months. The damp piece of string connecting me to the World Wide Web will shortly be replaced with a big, fat fibre optic cable, hopefully enhancing the experience for both the speaker and the listening audience.

I'll still keep my camera turned off ... 'good face for radio' and all that 😉.

In between delivering talks I'll also be preparing one or two more for the future. I've got one in mind that covers both honey bee biology and the 'Bigger queens, better queens' series of posts that I wrote earlier this year. Preparing 50+ 'slides' (I still think of them as slides, as that was how I started using a Magic Lantern 😉), the necessary images and the accompanying text takes a long time, so the talk will be re-used ... hence repeating myself.

Many associations run winter talk programmes. If you attend - either in person or online - take advantage of the question and answer session afterwards. As a speaker I'm often surprised at the reticence of some audiences to ask questions ... either on the talk or other aspects of beekeeping.

Don't be shy.

"There's no such thing as a stupid question".

Repositioning and removing

And finally (in an even more contrived manner I've kept the alliteration going), Apivar users should reposition the strips in late autumn, and remove them before winter.

I mentioned repositioning the strips in a recent post. This should be done about halfway through the 8-10 week treatment period. Each strip should be lifted, cleaned of wax and propolis - at the same time scratching the surface of the strip with the hive tool to help 'release' the miticide - and then repositioned immediately adjacent (on either side) of the ever-shrinking brood nest. Amitraz, the active miticide, works by contact and this maximises efficacy. The limited data I've seen suggest the benefits of doing this are small - a few percent - but there's no reason that marginal gains should be the sole preserve of Team Sky {{10}}.

The only good mite, is a dead mite.

Once treatment is complete, remove and discard the Apivar strips. Leaving the strips in the hive overwinter, each leaching out a small and diminishing - non-lethal - dose of amitraz, is probably a good way to help in the selection of amitraz resistance in Varroa. This, whilst an interesting topic (and one I'll be returning to), is to be avoided so that amitraz-containing miticides remain an effective tool for mite control in the future.

I started Apivar treatment in mid/late-August, so the strips will be removed - whatever the weather - from about the last fortnight of October.

It's a simple, but important, task and will probably be the last time I'll open a hive this year.

Perhaps a downbeat thought to end this post on, but there's no shortage of things to do before the season starts again.

Sponsor The Apiarist

The Apiarist covers 'the science, art and practice of sustainable beekeeping ... so much more than honey' and only exists because of the countless hours I spend mumbling incoherently into Google's voice memo app and abbreviating the resulting verbiage (in fact, it's just typed ... my train of thought is too garbled to dictate effectively).

If this, or other, posts has helped or inspired your beekeeping, or was amusing or enlightening, then please consider sponsoring The Apiarist.

Sponsorship costs less than £1/week annually, or little more than a large cappucino monthly. Sponsors help ensure the weekly posts appear, receive an irregular (approximately monthly) newsletter, and have access to an increasing number of sponsor-only content ... those starred ⭐ in the lists of posts.

Alternatively, you can help reduce my caffeine overdraft ... and please spread the word to encourage other beekeepers (or non-beekeepers ... the more the merrier) to subscribe.

Thank you.

{{1}}: Which might be 10, 100 or 1000 jars, depending upon the scale you operate at.

{{2}}: No automated labelling machines here!

{{3}}: And, since my records are all digital, I can easily erase evidence of my arrogance/confidence if misplaced.

{{4}}: Note to the BBKA, it's a name - after Marcello Malpighi - so should be capitalised.

{{5}}: It's four in larva, in case you're interested, but 100 in adult workers. Why so many more? That's a much more interesting question.

{{6}}: I've written this from a UK-centric viewpoint, though I'm sure there are equivalent qualifications, certificates and titles in other countries.

{{7}}: Varroa for most of us, but small hive beetle for some, and the yellow-legged hornet for increasing numbers of beekeepers.

{{8}}: Unless you are a wasp.

{{9}}: Perhaps as little as one third of the annual rainfall.

{{10}}: The fact that some of their marginal gains might have involved testosterone doping can be safely ignored here.

Join the discussion ...