Apis mellifera aquaticus

June in Fife was the wettest year on record. It started in a blaze of glory but very quickly turned exceedingly damp. The photo above was taken on the 7th of June. One of my apiaries is in the trees at the back of the picture. Six queens emerged on the 2nd or 3rd of June to be faced with a week-long deluge. The picture was taken on the first dry morning … by the afternoon it was raining again, so delaying their ability to get out and mate (hence prompting the recent post).

And so it continued …

Here’s the same view on the 1st of July. Almost unchanged … ankle deep water en route to the apiary, the burn in flood and some splits and nucs now being fed fondant to prevent them starving.

A beautiful morning though ?

Retrospective weather reports

Of course, you shouldn’t really worry about weather that’s been and gone, though comparisons year on year can be interesting. At the very least, knowing that the June monthly rainfall in Eastern Scotland was 223% of the 1961-99 average, I’ll have an excuse why queens took so long to mate and why the June gap was more pronounced than usual. Global warming means summers are getting wetter anyway, but even if you make the comparison with the more recent 1981-2010 average we still got 206% of the June monthly total.

The Met Office publishes retrospective summaries nationally and by region. These include time series graphs of rainfall and temperature since 1910 showing how the climate is getting warmer and wetter. If you prefer, you can also view the data projected on a map, showing the marked discrepancies between the regions.

Parts of the Midlands and Lewis and Harris were drier than the June long-term average, but Northern England and Central, Southern and Eastern Scotland were very much wetter.

It would be interesting to compare the year-by-year climate changes with the annual cycle of forage plants used by bees. Natural forage, rather than OSR where there is strain variation of flowering time, would be the things to record. As I write this (first week of July) the lime is flowering well and the bees are hammering it. The rosebay willow herb has just started.

Prospective weather forecasts

Bees are influenced by the weather and so is beekeeping. If the forecast is for lousy weather for a fortnight it might be a good idea to postpone queen rearing and to check colonies have sufficient stores. If rain is forecast all day Saturday then inspections might have to be postponed until Sunday.

If you have a bee shed you can inspect when it’s raining. The bees tolerate the hive being opened much better than if it were out in the open. Obviously, all the bees will be in residence, but their temper is usually better. They exit the shed through the window vents and rapidly re-enter the hive through the entrance.

I don’t think there’s much to choose between the various online weather forecast sites in terms of accuracy, particularly for predictions over 3+ days. They’re all as good or as bad as each other. I cautiously use the BBC site, largely because they have an easy-to-read app for my phone.

Do I need an umbrella?

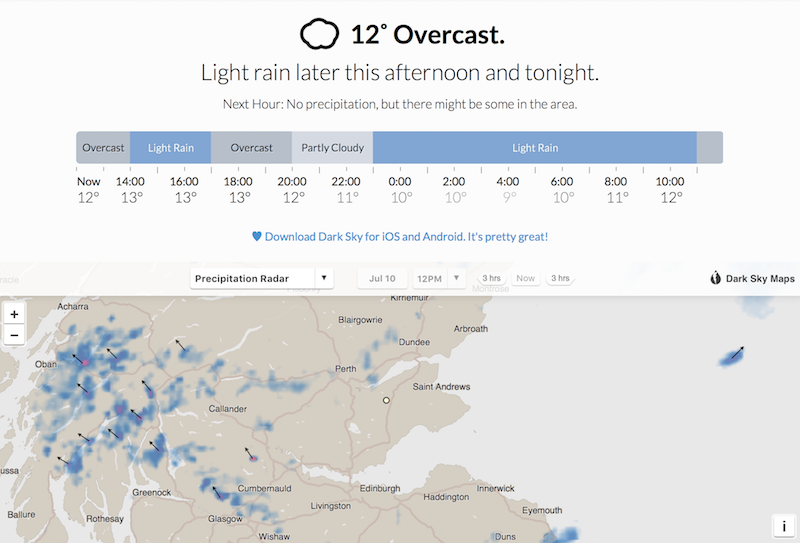

For shorter-term predictions (hours rather than days) I’ve been using Dark Sky. This can usefully – and reasonably accurately – predict that it will start raining in 30 minutes and continue for an hour, after which it will be dry until 6pm.

The forecast in your area might be different ?

There’s a well designed app for iOS and Android as well that has neat graphics showing just how wet you’re likely to get, how long the rain will last and which direction the clouds will come from.

It’s far from perfect, but it’s reasonably good. It might make the difference between getting to the apiary as the rain starts as opposed to having a nice cuppa and then setting off in an hour or two.

Rain stopped play

I’ve posted recently on delays to queen mating caused by the poor weather in June. I’ve now completed inspections of all the splits. Despite both keeping calm and having patience I was disappointed to discover that the last two checked had developed laying workers. Clearly the queen was either lost on her mating flight or – more likely (see the pictures above) – drowned.

I’ve previously posted how I deal with laying workers – I shake the colony out and allow those that can fly to return to a new hive on the original site containing a single frame of eggs and open brood. If they start to draw queen cells in 2-3 days I reckon the colony is saveable and either let them get on with it, or otherwise somehow make them queenright.

One of the laying worker colonies behaved in a textbook manner. A couple of days after shaking them out there were queen cells present. I knocked these back and united the with a spare nuc colony containing a laying queen.

The second colony behaved very strangely. I didn’t manage to inspect them until a week after shaking them out. There were no queen cells. Nor was there any evidence of laying worker activity in the frames of drawn comb I’d provided them with. Instead, they’d filled the brood box with nectar from the nearby lime trees. Weird. I united them with a queenright colony and I’ll check how they progress over the next week or two.

Apis mellifera aquaticus

My colonies are usually headed by dark local mongrel queens. My queen rearing records show that some are descended from native black bees (Apis mellifera mellifera) from islands off the West coast of Scotland, albeit several generations ago. These bees are renowned for their hardiness, ability to forage in poor weather and general suitability to the climate of Scotland.

Nevertheless, without further natural selection and evolution they will have still needed water wings, a snorkel and flippers to get mated last month ?

Colophon

Carl Linnaeus

The taxonomic scheme ‘developed’ by Carl Linnaeus (1707 – 1778) is a rank-based classification approach actually dates back to Plato. In it, organisms are divided into kingdoms (Animals), classes (Insecta), order (Hymenoptera), family (Hymenoptera), genera (Apis) and species (mellifera).

The subspecies is indicated by a further name appended to the end of the species name e.g. Apis mellifera capensis (Cape Honey bees), Apis mellifera mellifera (Black bees)

Apis mellifera aquaticus doesn’t really exist, but might evolve if it remains this wet ?

Join the discussion ...