Apiguard advice

A few months ago I discussed the instructions supplied with some formic or oxalic acid-containing miticides beekeepers use to control Varroa. The post was titled ’Infernal contradictions’ reflecting the state of the documentation provided, either with the purchased products or via the Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) database of approved treatments.

Are the instructions clear, unambiguous, meaningful, accurate and helpful?

Sometimes … but not always 🙁 .

This time I’m turning my attention to Apiguard, a thymol containing miticide that – used properly – is very effective at reducing Varroa levels. It’s an organic treatment and there is no evidence that mites can become resistant to the active ingredient.

Effective and no resistance … what’s not to like?

Be patient … I’ll come to that in due course.

I no longer use Apiguard (for reasons that will become clear) but did use it, reasonably successfully, for years when I lived in the Midlands. In surveys of miticide usage, Apiguard is one of (or often the) most widely used in the UK, so this post should be relevant for many readers.

This is a long post. Apiguard, like other miticides, is not ‘fit and forget’. I you want it to work well you need to use it properly. This means you probably need to understand how it works and do more than read the instructions {{1}}.

Good and bad practice

If you are going to reduce mite levels using chemicals you want to do so in a way that:

- maximises the impact on the mite population using the minimal effective dose and/or duration of treatment to avoid damage to the colony

- does not breach the guidelines in terms of approved method, dose, duration or state of the colony when they are treated

For example, a single treatment with Api-Bioxal during a broodless period in the winter slaughters ~90-95% of mites and is well tolerated by the bees. The treatment is approved and is applied when it is likely to have maximum effect on Varroa but minimum impact on the colony.

This is an example of good practice.

In contrast, interleaving every frame in the brood box with unbranded fluvalinate strips purchased via eBay from China in a hive with two rapidly-filling supers is definitely not good practice {{2}}. The chemical strips might have contained tau-fluvalinate (the active ingredient in Apistan) but were not approved by the VMD, the dosage was far too high and any honey would be tainted and unfit for human consumption.

Any instructions provided with authorised treatments, or additional documentation and advice from the manufacturer/supplier, should make the safe and effective administration of the chemical straightforward i.e. enabling good practice.

How does Apiguard do in this regard? {{3}}

Apiguard

The active ingredient in Apiguard is thymol, a natural compound present in thyme and a range of other plants. Apiguard is supplied in foil trays {{4}} containing 50 g of a white gel-like compound. 25% (12.5 g) of this is thymol, the remainder is a slow-release carrier that ensures thymol production occurs over a protracted period of days or weeks.

The bees need access to the tray of Apiguard for it to work so it is normally placed on the top bars of the brood frames, with ‘headspace’ provided by an eke. The natural housekeeping activity of workers removes the gel, distributing it around the hive.

Thymol appears to be active against Varroa as a vapour and possibly also by direct contact. Distribution of the gel around the hive presumably increases this contact, but – on account of the slow release formula – also ensures that the thymol vapour is maintained at therapeutic (i.e. effective) concentrations for a long period, thereby killing phoretic mites and those released when new workers emerge.

Thymol does not penetrate brood cappings, or kill mites in cells, so the effective vapour concentration must be maintained for at least one full brood cycle.

In practice treatment takes a minimum of one month.

Note Please remember that I’m UK based when I discuss allowed usage methods and recommendations … it might be different in your country. The mechanism of action will of course be the same wherever you are, so my comments about temperatures, volumes, durations etc should all be valid.

Thymol vapour concentration

The vapour concentration of thymol needed to be effective against Varroa is apparently 5-15 micrograms per litre (µg/l) of hive air. These figures are from a Bee Culture article by Claudio Garrido and I have been unable to find any published information on this directly from the manufacturer, Vita Europe Ltd.

Thymol vapour production is temperature dependent.

At low temperatures vapour production is low and it increases with increasing ambient temperature. On a really warm day – say above 30°C – hives being treated with Apiguard smell very strongly of thymol. The vapour concentration can be so high that the bees may ‘beard’ at the hive entrance.

Used appropriately, and as reported in several tests of the product, Apiguard can kill 90-95% of the mites in a colony. Vita report testing it in 10 countries in Europe, the Middle East and North America with an average efficacy of 93%.

That’s more than acceptable {{5}} and should significantly improve the health and hence overwintering colony survival of our bees.

However, testing in northern Italy or two regions of Germany – all areas with lower temperatures – was reported to give 67%, 43% and 72% efficacy, all of which are too low to effectively control Varroa levels in the colony.

So, in summary Apiguard is:

- a miticide based upon a natural plant product i.e. organic

- easy to administer

- distributed around the hive by workers during hive cleaning activity

- dependent upon the ambient temperature to achieve a sufficiently high vapour concentration to kill mites

- extensively tested (though predominantly in warm countries)

Instructions for use

These are lifted from the paperwork provided on the VMD database, specifically the current QRD ‘labelling and package leaflet’ documentation (revised March 2020). I’ll only mention the key points that are relevant to the rest of the post.

- do not use during a honey flow

- two applications of 50 g of gel per colony at a 2 week interval

- after the first fortnight remove the first tray and replace with a fresh tray, leave until the tray is empty

- maximum of two treatments per year

- use in late summer after the honey harvest (when brood present is diminishing)

- may be used in springtime when temperatures are above 15°C

- do not use the product when the maximum daily temperature expected during the treatment is lower than 15°C or when the colony activity is very low or when temperature is above 40°C

A search of the Vita Europe Ltd. website turns up some additional information on Apiguard including a number of scientific-looking studies on application and efficacy, all supplied as PDFs {{6}}. ’Scientific-looking’ because it’s not clear whether all the studies have been peer reviewed and published. Of course, this doesn’t mean they’re wrong or not worth reading. If they are published it would have been useful to provide appropriate links.

Importantly, since these documents are distributed by Vita Europe Ltd. I consider their contents are correct and approved by Vita … which becomes relevant when we consider temperature.

Which we’ll do now 😉 .

Temperature

Temperature is critical because it determines whether the thymol reaches a therapeutic vapour concentration. If the temperature is too low the vapour concentration will be too low to kill the mites.

In terms of minimum environmental temperature the instructions simply state:

- may be used in springtime when temperatures are above 15°C

- do not use the product when the maximum daily temperature expected during the treatment is lower than 15°C

Which, to be honest, isn’t hugely helpful.

The daily temperatures last weak peaked at just over 15°C but the average temperature was appreciably lower.

Are those appropriate conditions?

With big day/night variations the daily maximum might reach 15°C but the colony may be semi-comatose most of the time, so reducing Apiguard distribution.

The Bee Culture article I mentioned earlier stated that, in tests conducted in Switzerland, a vapour concentration of only 4 µg/l was achieved and this was below the therapeutic concentration, meaning that fewer mites were killed. Unfortunately, there was no citation I could find for the source of this information.

Why does this matter?

Because I keep bees in a temperate northern hemisphere country and late summer/early autumn daily maximum temperatures are often around the 15°C mentioned in the Apiguard instructions.

If the miticide does not reach the therapeutic concentration it will not be effective … it does not matter if you leave the treatment on for longer, many mites will survive.

It’s effectively the same as using antibiotics at too low a dose …

Read the FAQ …

Helpfully, Vita Europe also produce an Apiguard FAQ (PDF).

It’s worth noting that the FAQ has obviously been written as a generic document, applicable wherever Apiguard is sold. It contains references to formulations not available in the UK and makes a number of statements that potentially or actually conflict with the Apiguard instructions provided with the product in the UK.

For example, it states that the dose is ’50 g per ten brood frames’.

Most UK brood boxes have 11 frames … but does it matter whether the frames are National, 14×12 or Langstroths? Those boxes all have significantly different volumes which will impact the active concentration of thymol achieved {{7}}.

It also includes reference to supers …

It is preferable to remove supers before treating with Apiguard. Apiguard may taint honey in supers, but it is unlikely, especially if the honey stores are sealed

To me, this implies that capped honey stores would be usable. They even add ‘Honey collected during Apiguard treatment can be fed back to the bees’.

There’s no mention of human consumption.

Does this contradict the UK regulations? These state that Apiguard should not be used during a honey flow. Does that mean that capped honey already present when treating during a dearth could be sold?

All a bit confusing, but I’m digressing … what about temperature?

There are two relevant comments in the FAQ:

The external temperature should be above approximately 15°C (60°F), which means that the colony is active.

… and …

Apiguard can work at low temperatures but is most effective when temperatures have a daily minimum of 15°C

Hmmm … I want it to be effective … ‘can work’ sounds a bit underwhelming.

… and the documents supplied by the manufacturer

I then read all of the additional documents referenced as ‘further information’ on the Vita website. A few make oblique references to temperature, but only a couple have explicit advice:

The first, whilst not referencing a specific temperature, is interesting:

The temperatures recorded inside the colony suggest that the average daily temperature should be considered a limiting factor on the use of evaporating products. Indeed, at the point of application of the thymol, the temperatures depend not only on those outside the colony, but also on the thermoregulating activities of the bees on the brood combs, solar irradiation and the materials used to construct the hive (from this PDF).

But the second reference to temperature could not be clearer:

The manufacturer recommends use of the product when the mean daily temperature varies between a minimum of 15°C and a maximum of 40°C (from this PDF).

Now we’re getting somewhere!

It was the latter document (from Apimondia 2007), together with analysis of local temperatures, that persuaded me that Apiguard was not an appropriate miticide for use in my part of Scotland.

Is it appropriate where you live?

Temperature, colony activity, thymol vapour and volume

Where Apiguard is concerned the temperature influences two things; the generation of the thymol vapour and the activity of the colony which distributes the thymol-containing gel around the hive.

If the temperature is too low the colony will be clustered and/or inactive and the vapour concentration will never get high enough to be effective against mites.

Not good.

Conversely, in warm weather when the nighttime temperature remains sufficiently high, the colony will be active in the hive all the time and the thymol vapour concentration will be high.

Be gone, pesky mites!

Presumably, if the temperature fluctuates – from cold nights to warm days – the colony will only be properly active during the warmer day but the vapour concentration may not be high enough during the cooler nights to be effective.

If I sound unclear on the latter point it’s because I am.

Within the clustered bees at night the temperature should remain high enough to help the thymol become a vapour but the warmed part of the hive will have a smaller volume. Because the hive air volume – which is what is circulating when the bees (and mites) respire – is the total volume of the brood box the overall vapour concentration will be lower.

Will it be too low to be effective?

I don’t know.

Number crunching

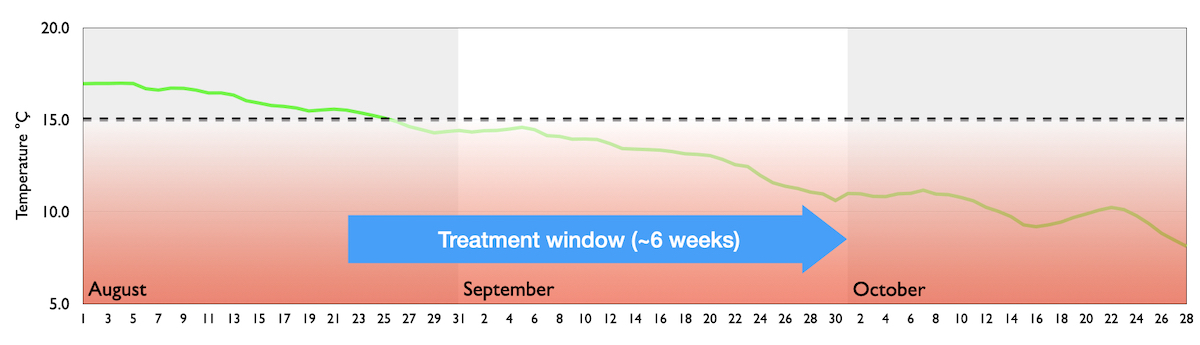

In my deliberations about using Apiguard in Scotland I used 15°C as a threshold temperature to help in my decision making. In the absence of any firm temperature data and thymol vapour concentration it was all I could work with.

All the graphs are for my Fife apiaries, but the same information could {{8}} be generated for anywhere in the country if you have access to local weather information (and I discussed last week how to access that).

Highs, lows and averages

Typically, the temperature during a 24 hour period fluctuates. Nights are usually colder than days. The temperature on successive days or nights also varies.

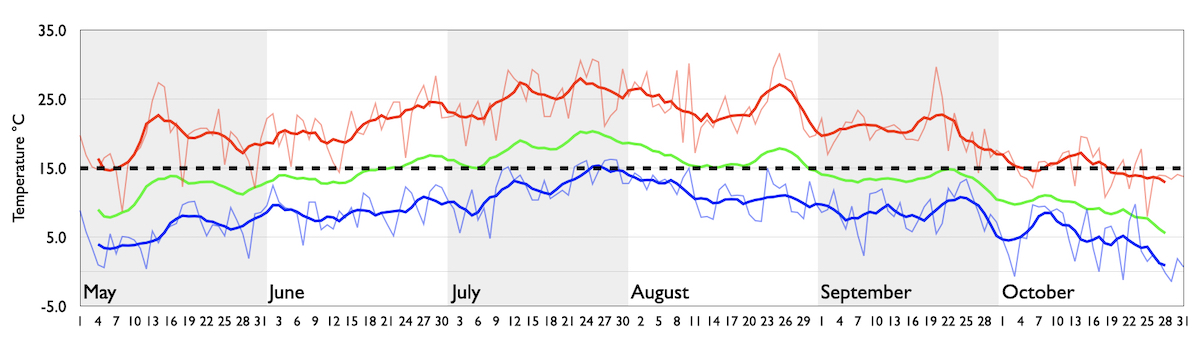

If you plot the maximum (red lines) and minimum (blue lines) temperature you get rather ‘noisy’ graphs (the thin lines) which can be smoothed by averaging the temperature over a longer period, for example 7 days (the thick lines).

In Fife, a 7 day sliding (i.e. days 1-7, 2-8, 3-9 etc.) average maximum daily temperature exceeds 15°C for most of the period May to mid-October. However the 7 day sliding minimum temperature almost never exceeds 15°C … at least for 2019 which is the year plotted in the graph above.

If you needed a minimum temperature of 15°C for Apiguard to work you’ve got a problem … at least in Fife {{9}}.

Perhaps more useful is the mean daily temperature. This is plotted in green above. If Apiguard needs a mean temperature of 15°C to work effectively then this is exceeded – in 2019 – from mid-June until late August.

The mean temperature is not calculated by adding the maximum and minimum temperature together and dividing by two. Instead it is determined from the regular (every 1-5 minutes typically) temperature readings over the entire 24 hour period.

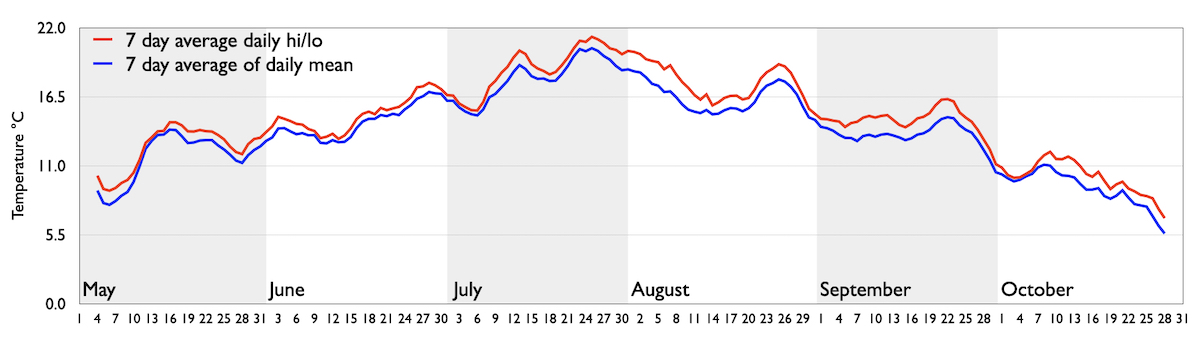

However, some personal weather stations only report daily highs and lows.

You can calculate an approximate mean daily temperature from these (Hi+Lo/2; red line above) but it will be an overestimate of the actual mean (blue line above), by ~0.5-0.9°C (in my experience).

Autumn treatment with Apiguard

Apiguard treatment is added as soon as the summer honey is taken off the hive. Typically for me this is either the second or third week of August.

The treatment period is a minimum of 4 weeks and – according to the FAQ – optimally 6 weeks. Throughout this period the temperature should be high enough (whatever that is) to achieve a thymol vapour concentration that is effective in killing mites.

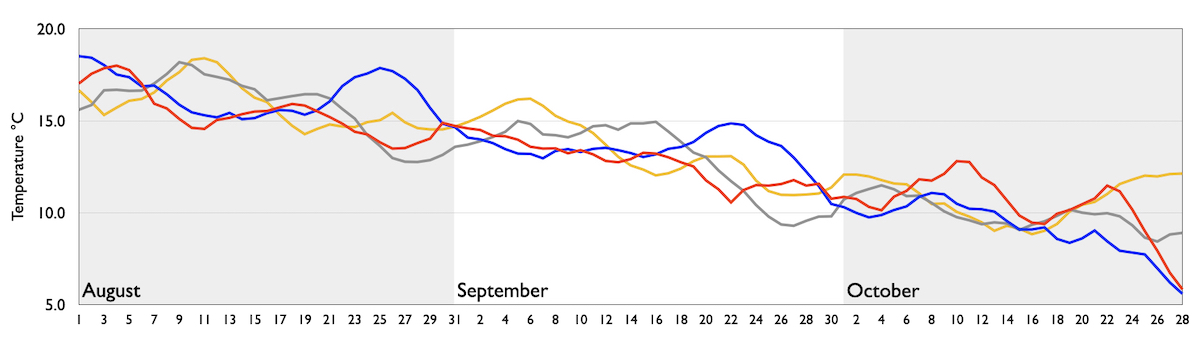

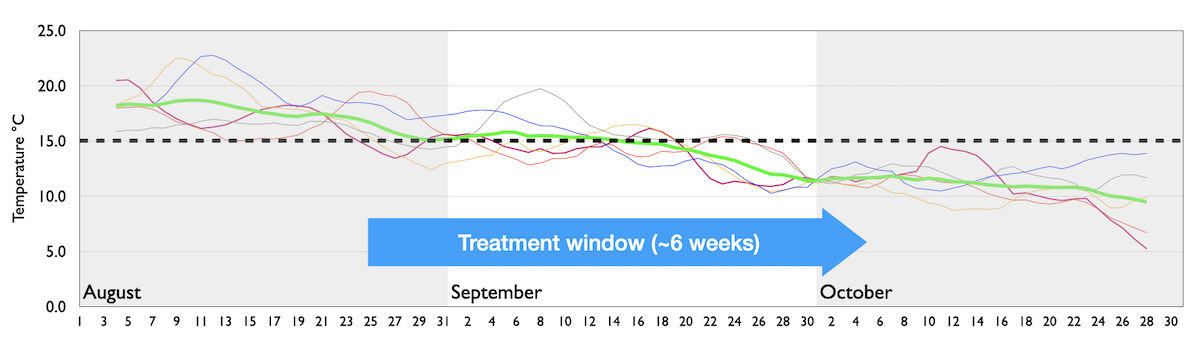

When doing this sort of analysis you cannot just look at data from one year as it might have been unseasonably cold or warm.

Here are the 7 day sliding mean daily temperatures for 2018-2020 and 2022 {{10}}.

Late August and late September were appreciably warmer in 2019 (the blue line). However, all those lines are still a bit of a mess, but if you take an average across several years you get a graph (below) that is much easier to interpret.

In my part of Scotland the mean daily temperature is usually below 15°C from the last week in August i.e. the entire time I would be expecting to use Apiguard if that was my chosen miticide treatment 🙁 .

I’ve shaded the area below 15°C to indicate that mite killing becomes increasingly ineffective the further the mean daily temperature is below this temperature.

Unfortunately, I don’t know the exact (mean daily temperature) threshold and Vita Europe Ltd. don’t provide this information in their instructions, FAQ or associated documentation 🙁 .

Decisions, decisions

If you want to use Apiguard you probably need to do a similar sort of analysis. If you don’t think my interpretation of the Vita Europe documentation is correct then read the paperwork and apply your own threshold.

I stopped using Apiguard when I moved from the Midlands to Scotland.

My overwintering colony losses in the Midlands were a little higher than they have ever been in Scotland. I have always assumed that this was because Scotland ‘benefits’ from colder winters. This means that there is almost always a broodless period between late October and mid/late December (usually earlier rather than later). This makes a ‘midwinter’ (but it isn’t) oxalic acid treatment very effective in killing off any mites that escaped the autumn treatment, or that have reproduced since then.

However, out of interest I retrospectively graphed (above) the mean daily autumn temperatures (August to October) for my Midlands apiary for five years (2018-2022; thin lines on the graph above) and the average of these years (thick green line).

The individual years plotted make for a noisy graph, but it’s reasonably clear that a typical 4-6 week Apiguard treatment window spanning from the last week in August until early October is likely to include a significant period (perhaps 50% of the time) when the mean daily temperature is below 15°C.

What would the consequences of this be?

Mites from capped cells that are released later during the treatment window may well not experience fatal thymol vapour concentrations. They will therefore escape treatment and will be able to go on to reproduce.

Perhaps my higher winter losses were due to ineffective Apiguard control of mite numbers … ?

Other considerations

I’ve concentrated on the influence of temperature because it is critical for effective thymol control of mites and because it is poorly explained in the Apiguard instructions.

However, it’s not the only thing to think about …

Queens

High thymol concentrations can stop queens from laying.

About 50% of my colonies would experience an enforced brood break during Apiguard treatment {{11}}. Since colonies should be rearing winter bees and colony strength is a primary determinant of overwintering survival, anything that stops the queen from laying is not ideal.

On the plus side I don’t ever remember losing a queen during Apiguard treatment.

’Headspace’

There’s a document on the Vita website that demonstrates that additional space around the Apiguard trays on the top bars increases the efficacy of treatment. Three different depth ekes were used – 6.5, 28.5 and 66.5 mm – and resulted in 78%, 87% and 92% of mites in the colonies to be killed.

So … more is better?

They conclude that the improved air circulation aids distribution of the thymol vapour, so making treatment more effective. The deepest eke would have increased the volume of the hive by ~12 litres (i.e. ~25% in the case of a National brood box).

Whilst these results are interesting it’s important to note that these experiments were conducted in Italy when the mean daily temperatures were 20-25°C.

In cooler climates I’m not certain that the same (or any?) improvement of treatment would be seen.

At lower temperatures the vapour concentration of thymol achieved will be lower anyway. If the volume of the hive is then increased by using a deep eke it may reduce the vapour concentration yet further, below a therapeutically effective level.

The FAQ recommends using an empty super … is this still recommended if the temperatures are low?

Apiguard advice

Apiguard works well if it is used properly, which includes appropriate local conditions. If you want to use Apiguard then I would suggest:

- check the local historical mean daily temperature for 4-6 weeks after your chosen treatment date. If a much of this period is likely to be below 15°C then treatment will be less effective. Indeed, it may not be effective enough to prevent mite and virus damage to your colonies.

- if your interpretation of the Vita-provided information is that 15°C is not an appropriate threshold then choose a better one when you do the analysis.

- add the Apiguard trays to the top bars surrounded by a shallow eke with a well-insulated crownboard to help boost the in-hive temperature.

- close the open mesh floor to retain the thymol vapour within the hive unless the weather is very warm. If you’re only achieving a low vapour concentration of thymol you want to keep as much as possible in the hive. Thymol vapour is denser than air.

- feed your colonies at the same time as you treat with Apiguard.

- monitor daily mean temperatures during treatment … if it is appreciably below 15°C {{12}} consider the need for an additional temperature-independent miticide.

- follow the current instructions provided with the product and read the additional information provided by Vita Europe Ltd.

- remember to keep a record of batch/lot numbers.

That might seem like a lot of work.

However, if you’re going to use a miticide it’s important you use it effectively.

If it doesn’t work you’re just wasting money and unnecessarily exposing bees to chemicals.

And, after all, there’s no actual beekeeping to be done at this time of the year 😉 .

Have fun

{{1}}: Because they’re not particularly good.

{{2}}: This is not a hypothetical example. I know someone who did exactly this. The colony did not survive. It’s not clear whether the treatment or the mites were responsible.

{{3}}: TL;DR … not great.

{{4}}: The 3 kg tubs and 25 g sachets are no longer sold in the UK. I’m not sure the sachets ever were.

{{5}}: Unless you’re a mite.

{{6}}: And some at such poor resolution that the tables/figures are unreadable.

{{7}}: I’ll return to the volume of the box at the end.

{{8}}: Should?

{{9}}: Remember the statement in the FAQ … “[use] when the mean daily temperature varies between a minimum of 15°C and a maximum of 40°C”.

{{10}}: I’m reusing the datasets from last week and you’ll remember that the 2021 data was incomplete.

{{11}}: I remember suggesting to Max Watkins from Vita that they should sell a line of queens selected that don’t stop laying.

{{12}}: Blah blah.

Join the discussion ...