A New Year, a new start

The short winter days and long dark nights provide ample opportunity to think about the season just gone, and the season ahead.

You can fret about what went wrong and invent a cunning plan to avoid repetition in the future.

Or, if things went right, you can marvel at your prescience and draft the first couple of chapters of your book “Zen and the Art of Beekeeping”.

But you should also prepare for the normal events you expect in the season ahead.

In many ways this year {{1}} will be the same as last year. Spring build-up, swarming and the spring honey crop, a dearth of nectar in June, summer honey, miticides and feeding … then winter.

Same as it ever was as David Byrne said.

That, or a pretty close approximation, will be true whether you live in Penzance (50.1°N) or Thurso (58.5°N).

Geographical elasticity

Of course, the timing of these events will differ depending upon the climate and the weather.

For convenience let’s assume the beekeeping season is the period when the average daytime temperature is above 10°C {{2}}. That being the case, the beekeeping season in Penzance is about 6 months long.

In contrast, in Thurso it’s only about 4 months long.

More or less the same things happen except they’re squeezed into one third less time.

Once you have lived in an area for a few years you become attuned to this cycle of the seasons. Sure, the weather in individual years – a cold spring, an Indian summer – creates variation, but you begin to expect when particular things are likely to happen.

There’s an important lesson here. Beekeeping is an overtly local activity. It’s influenced by the climate, by the weather in an individual year, and by the regional environment. You need to appreciate these three things to understand what’s likely to happen when.

Late April 2016, Fife … OSR and snow

Events are delayed by a cold spring, but if there’s oil seed rape in your locality the bees might be able to exploit the bounteous nectar and pollen in mid-April.

Mid-April 2014, Warwickshire

Foraging might extend into October in an Indian summer and those who live near moorland probably have heather yielding until mid/late September.

Move on

You cannot make decisions based on the calendar.

In this internet-connected age I think this is one of the most difficult things for beginners to appreciate. How many times do you see questions about the timing of key events in the beekeeping season – adding supers, splitting colonies, broodlessness – with no reference to where the person asking, or answering, the question lives?

It often takes a move to appreciate this geographical elasticity of the seasons at different latitudes.

When I moved from the Midlands to Scotland {{3}} in 2015 I became acutely aware of these differences in the beekeeping season.

When queen rearing in the Midlands my records show that I would sometimes start grafting in the second week in April. In some years I was still queen rearing in late August, with queens being successfully mated in September.

Locally bred queen …

In the last 5 years in Scotland the earliest I’ve seen a swarm was the 30th of April and the latest I’ve had one arrive in a bait hive was mid-July. Here, queen rearing is largely restricted to mid-May to late-June {{4}}.

All of this is particularly relevant as most of my beekeeping is moving from the east coast to the west coast of Scotland this year.

I’m winding down my beekeeping in Fife and starting afresh on the west coast.

The latitude is broadly the same, but the local environment is very different.

And so are the bees … which means there are some major changes being planned.

What are local bees?

I’m convinced about the benefits of local bees. The science – which I’ve discussed in several previous posts – shows that locally-reared bees are physiologically adapted to their environment and both overwinter and survive better.

But what is local?

Does it mean within a defined geographical area?

If so, what is the limit?

Five miles?

Fifty miles?

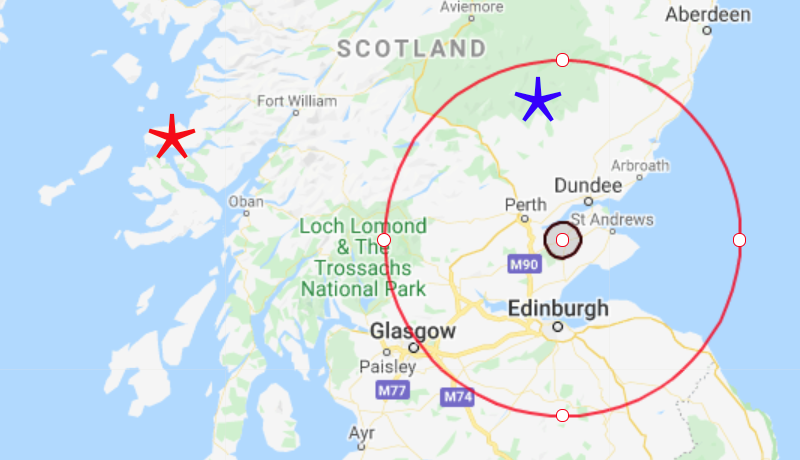

What is local? Click to enlarge and read full legend.

I think that’s an overly simplistic approach.

The Angus glens are reasonably ‘local’ to me. Close enough to go for an afternoon walk, or a summer picnic. They’re less than 40 miles north as the bee flies {{5}}.

However, they’re a fundamentally different environment from my Fife apiaries. The latter are in intensively farmed, low lying, arable land. In Fife there’s ample oil seed rape in Spring, field beans in summer and (though not as much as I’d like) lime trees, clover and lots of hedgerows.

The Angus glens

But the Angus glens are open moorland. There’s precious little forage early in the season, but ample heather in August and September. It’s also appreciably colder in the hills due to the altitude {{6}}.

I don’t think you could keep bees on the Angus hills all year round. I’m not suggesting you could. What I’m trying to emphasise is that the environment can be dramatically different only a relatively short distance away.

My bees

I don’t name my queens {{7}} but I’m still very fond of my bees. I enjoy working with them and try and help them – by managing diseases, by providing space or additional food – when needed.

I’ve also spent at least a decade trying to improve them.

Every year I replace queens heading colonies with undesirable traits like running on the comb or aggression or chalkbrood. I use my best stocks to rear queen from and, over the years, they’ve gradually improved.

They’re not perfect, but they are more than adequate.

When I moved from the Midlands to Scotland I brought my bees with me.

Delivering bees from the Midlands to Fife

I ‘imported’ about a dozen colonies, driving them up overnight in an overloaded Transit van. The van was so full of hive stands, empty (and full) beehives and nucs that I had a full hive strapped down in the passenger seat. Fortunately the trip went without a hitch (or an emergency stop 🙂 ).

Passenger hive

They certainly were not ‘local’ but I’d invested time in them and didn’t want to have to start again from scratch. In addition, some hives were for work and it was important we could start research with minimum delay.

But I cannot take any of my bees to the west coast 🙁

Treatment Varroa free

Parts of the remote north and west coast of Scotland remain free of Varroa. This includes some of the islands, isolated valleys in mountainous areas and some of the most westerly parts of the mainland.

It also includes the area (Ardnamurchan) where I live.

Just imagine the benefits of not having to struggle with Varroa and viruses every season 🙂

Although I don’t feel as though I struggle with managing Varroa, I am aware that it’s a very significant consideration during the season. I know when and how to treat to maintain very, very low mite levels, but doing so takes time and effort.

It would certainly be preferable to not have to manage Varroa; not by simply ignoring the problem, but by not having any of the little b’stards there in the first place 😉

Which explains why my bees cannot come with me {{8}}. Once Varroa is in an area I do not think it can be eradicated without also eradicating the bees.

A green thought in a green shade … Varroa-free bees on the west coast of Scotland

I’ve already got Varroa-free bees on the west coast, sourced from Colonsay.

Is Colonsay ‘local’?

Probably. I’d certainly argue that it’s more ‘local’ to Ardnamurchan than the Angus glens are to Fife, despite the distance (~40 miles) being almost identical. Both are at sea level, with a similar mild, windy and sometimes wet, climate.

Sometimes, in the case of Ardnamurchan, very wet 🙁

My cunning plans

Although the season ahead might be “same as it ever was”, the beekeeping certainly won’t be.

My priorities are to wind down my Fife beekeeping activities (with the exception of a few research colonies we will need until mid/late 2022) and to expand my beekeeping on the west coast.

Conveniently, because it’s something I enjoy and also because it’s not featured very much on these pages recently, these plans involve lots of queen rearing.

Queen rearing using the Ben Harden system

In Fife I’m intending to split my colonies to produce nucs for sale. I’ll probably do this by sacrificing the summer honey crop. It’s easier to rear queens in late May/June and the nucs that are produced can be sold in 2021, or overwintered for sale the following season.

If I leave the queen rearing until later in the summer I would be risking either poor weather for queen mating, or have insufficient time to ensure the nucs were strong enough to overwinter.

It’s easier (and preferable) to hold a nuc back by removing brood and bees than it is to mollycoddle a weak nuc through the winter.

And on the west coast I’ll also be queen rearing with the intention of expanding my colonies from two to about eight. In this case the goal will be to start as early as possible with the aim of overwintering full colonies, not nucs. However, I’ve no experience of the timing of spring build up or swarming on the west coast, so I’ve got a lot to learn.

Something old, something new

I favour queen rearing in queenright colonies. This isn’t the place to spend ages discussing why. It suits the scale of my beekeeping, the colonies are easy to manage and it is not too resource intensive.

I’ve written quite a bit about the Ben Harden system. I have used this for several years with considerable success and expect to do so again.

I’ve also used a Cloake board very successfully. This differs from the Ben Harden system in temporarily rendering the hive queenless using a bee-proof slide and upper entrance.

Cloake board …

Using a Cloake board the queen cells are started under the emergency response, but finished in a queenright hive. It’s a simple and elegant approach. In addition, the queen rearing colony can be split into half a dozen nucs for queen mating, meaning the entire thing can be managed starting with a single double brood colony.

One notable feature of the Cloake board is that the queen cells are raised in a full-sized upper brood box. During the preparation of the hive this upper box becomes packed with bees {{9}}. This means there are lots of bees present for queen rearing.

Concentrating the bees …

It’s definitely a case of “the more the merrier” … and, considering the size of my colonies, I’m pretty certain I can achieve even greater concentrations of bees using a Morris board.

A Morris board is very similar to a Cloake board except the upper face has two independent halves. It’s used with a divided brood box (or two 5 frame nucleus boxes) and can generate sequential rounds of queen cells. I understand the principle, but it’ll be a new method I’ve not used before.

Since the bees are concentrated into half the volume it should be possible to get very high densities of bees using a Morris board.

And since I like building things for beekeeping {{10}}, that’s what I’m currently making …

Which explains why I’ve got bits of aluminium arriving in the post, chopped up queen excluders on my workbench and Elastoplast on three fingers of my left hand 🙁

Happy New Year!

Notes

I’m rationalising my beekeeping equipment prior to moving. I have far too much! Items surplus to requirements – currently mainly flat-pack National broods and supers – will be listed on my ‘For Sale’ page.

{{1}}: I’m writing this in late December, but trying to remember it’ll be posted on the 1st of January … I apologise if the tenses are butchered even more so than normal.

{{2}}: It isn’t, but it’ll do as a rough approximation. At times of the year when the average daytime temperature exceeds 10°C there’s a good chance that the bees will be active, even if only for an hour or so around lunchtime.

{{3}}: Just a further 4°N in latitude … or ~275 miles.

{{4}}: Though in fairness, I’ve not tested the limits by trying to rear queens later than this.

{{5}}: Barely 0.2° increase in latitude.

{{6}}: The hills are 200-800 metres above sea level, with an assumed temperature decrease of ~1°C / 100 metres.

{{7}}: But I don’t criticise those that do.

{{8}}: I also don’t use the same bee suit, hive tools, smoker etc., and will be rigorously checking and cleaning other beekeeping equipment I transfer in due course.

{{9}}: I’ve discussed how previously, so won’t repeat the gory details here.

{{10}}: And resent paying £30+ for a few bits of wood and a small square of queen excluder.

Join the discussion ...