2019 in retrospect

The winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, is tomorrow. It will be a long time until there’s any active beekeeping, but at least the days are getting longer again 🙂

The queens in your colonies will soon – or may already – be laying again.

What better time to look back over the past season? How did the bees do? How did you do as a beekeeper? What could be done better next time?

Were there any catastrophic errors that really must not be repeated?

Overview of the season

Overall, in my part of Scotland, it was about average.

But that, of course, obscures all sorts of detail.

Spring was warm and swarming started early. I hived my first swarm before the end of April and my last in early July. This is about twice the length of the usual swarming season I’ve come to expect in Scotland. However, it wasn’t all frantic swarm management as there was a prolonged ‘June gap’ during which colonies were much more subdued.

The summer nectar, particularly the lime, was helped by some rain, but the season was effectively over by mid-August. I don’t take my colonies to the heather. Overall, the honey crop was 50-60% that of the (exceptional) 2018 season.

Looking at the yields from different apiaries for spring and summer it’s clear that – despite the warm spring – colonies did less well on the early season nectar (~40% that of 2018). I suspect this is due to their being less oil seed rape (OSR) grown within range of my apiaries. The colonies were strong, but the OSR just wasn’t close enough to be fully exploited..

Over recent years the area of OSR grown has reduced, a trend that is likely to continue.

The winter rape is already sitting soggily in the fields; I’ve chatted to a couple of the local farmers and will move some hives onto these fields if colonies are strong enough and the weather looks promising.

Bait hives

Every year I’ve been back in Scotland I’ve put a bait hive in the garden.

Every year it has attracted a swarm.

This year – with the extended swarming season – it led to the capture of three swarms in about 10 days. As the June gap ended the weather got quite hot and sultry {{1}} and the first swarm arrived near the end of that month.

One week after the first swarm arrived there was lots more scout bee activity. There were also quite a few dead or dying bees littering the ground underneath the bait hive. It turned out that these were the walking wounded (or worse) scout bees from two different hives fighting.

Within 48 hours another swarm arrived and I was fortunate enough to watch it descend.

Incoming!

I moved the hive that evening, placing another bait hive on the same spot. By the following morning there were yet more scout bees checking the entrance and a third swarm – by far the biggest of the three – arrived later that day.

Each was a prime swarm and none were from my own hives which are in the only apiary {{2}} within a mile of the bait hive.

Watching the scout bees check out a bait hive is always interesting. There’s a fuller account of the observations and lessons learnt – of which there were several – written in the post titled BOGOF (buy one get one free 😉 ).

Swarm prevention

My swarm prevention this year either used the nucleus method or vertical splits (with an occasional Demaree for good measure) for most hives. All prevented the loss of swarms and queen mating went about as well – or badly – as it usually does i.e. never as fast as I’d like, but (eventually) all were successful.

I did miss a couple of swarms. One relocated underneath the OMF of the hive it originated from because the queen was clipped and, having fallen ignominiously to the ground, she just clambered up the hive stand again.

The second swarm was also not lost as I inadvertently trapped the queen on the wrong side of the queen excluder. D’oh! In my defence, I’ve had a rather busy year at work {{3}} and it’s little short of a miracle that I got any beekeeping – let alone swarm control – done at all.

Mites

Considering the extended June gap, which resulted in a brood break for some colonies, mite levels were appreciably higher this year than last. I think this can largely be attributed to the warm Spring which allowed colonies to build up fast. Several colonies were strong enough to swarm in late April.

I do a limited amount of mite counting during the season but also monitor virus loads in emerging bees in our research colonies. In most colonies these stayed resolutely low and no production colonies needed any mid-season interventions for mite control.

Newly-arrived swarms were treated as were some broodless splits. The former because many swarms carry a larger than expected mite population {{4}} and the latter because it’s an ideal opportunity to target mites as – in the absence of brood – all will be phoretic.

All colonies were treated with Apivar immediately after the summer honey came off. At the same time they were fed copious amount of fondant in preparation for the winter ahead.

In late November most colonies were broodless and were treated with a vaporised OA-containing miticide.

What worked well

In what was a pretty tough year for non-beekeeping reasons even small beekeeping successes have assumed a significance out of all proportion to the effort expended on them.

In my first year or two of beekeeping honey extraction was an unbridled pleasure. As hive numbers increased it because more of a chore. An electric extractor marginally improved things.

However, there was still the never-ending juggling of frames trying to balance the extractor and jiggling of the unbalanced machine as it sashayed across the floor.

Two years ago I purchased some rubber braked wheels to add to the extractor legs.

This year I finally got round to fitting them.

The jiggle-free revolutions were a revelation 🙂

I know some beekeepers who stand their extractors on foam pads. Others who have them bolted to a triangular wooden platform. I can’t imagine either solution works better than these castors, which also make moving the extractor to and from storage much easier.

I changed my hive numbering system this season. I’d previously referred to hives by position or with a number written on the box. This caused some issues with the (sometimes shambolic) way I do my beekeeping.

If the hive moves and it’s numbered by position then its number should change. Manageable, but a bit of a pain.

If the position does not change but they’re expanded from a nuc to a full brood box do they get a new number or retain the old one? A problem if it’s written on the box.

And what happens when you move queens about in the apiary (which we sometimes need to do for work)?

All hives and queens were assigned a number – small red discs for the queen and big, bold numbers for the box. They stay with the colony or the queen … and the records 😉

This has worked very well. As colonies expand the numbers move, if queens are moved I know from and to where (and keep a separate record of queen performance). When colonies are united the queenless component loses both the queen number and the colony number.

The numbering has been a great success. The numbers themselves less so. Most of the red discs have faded very badly and a few of the hive numbers have cracked and/or blown away.

Never mind … the system works as intended and it has significantly improved my record keeping. I now know which hive and queen I’m referring to 😉

The Apiarist in 2019

I might squeeze in a more thorough overview of funny search terms and page accesses before the New Year. Briefly … there are significantly more subscribers and an increase of ~20% in overall page reads.

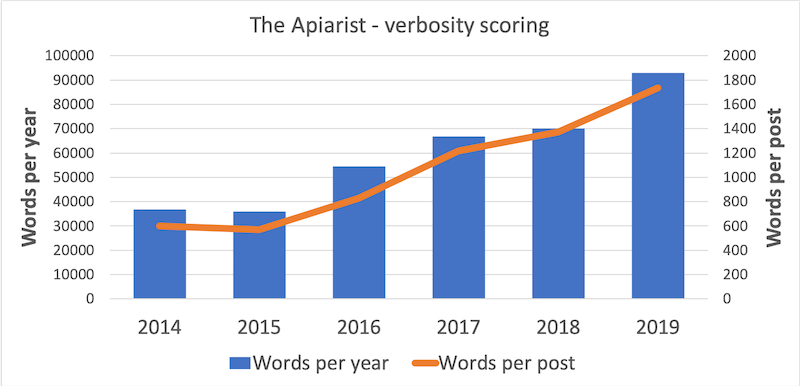

This year marks the sixth full season of The Apiarist which still surprises me. There still seem to be things to write about. Post length continues to increase, though the overall number of posts remain almost exactly one a week. Amazingly I’ve written nearly 95,000 words this year.

We had some server issues but most of these appear to have been resolved. Spam remains a problem and the machine auto-filters several hundred messages a day to keep my inbox only unmanageably overflowing. It has meant I’ve had to add some “I am not a robot” CAPTCHA trickery to the contact and/or comment forms. I’m aware that this has caused some problems making contact but can’t find an alternative solution that doesn’t swamp me in adverts for fake sunglasses, Bitcoins or Russian brides.

I live in Scotland and have no use for any of these things 😉 {{5}}

The year ahead

There are three main items on the ‘to do’ list for 2020 {{6}}.

The first is to start queen rearing again. Pressure of work has prevented this from happening over the last couple of seasons and I’m missing both the huge satisfaction it brings and the improved control over stock improvement. I’ve done lots of queen rearing in the past, but work has muscled its way in to too many weekends and evenings recently {{7}}.

I now have some perfectly adequate bees.

Actually, although they’re far from ‘perfect’ they are also far better than ‘adequate’.

I’ve got a couple of lines that have too much chalkbrood and almost all of them are less stable on the comb than I’d like. They don’t fall in wriggling gloops off the corner of the frame as some do, but they’re more active than I’d prefer. It’s a trait that has crept into some stocks over the last couple of years and I need to try and get rid of it.

The second is to provide better information on the provenance of my honey to potential and actual purchasers. There’s increasing interest in sourcing high quality local food and, as I’ve discussed recently on honey pricing, we should be aiming to provide a premium product (at a premium price 😉 ). The public are also increasingly aware that some of the major supermarkets have been reported to be selling adulterated honey. Providing details of the batch, the apiary and the area in which it was produced should help define it as a quality local product.

And generate repeat business.

Finally, I’m planting up a new apiary on the west coast with dozens of pollen-bearing trees before I start beekeeping there. This has been a long and protracted process as it has involved clearing large areas of invasive rhododendron. The first 125+ native trees go in this winter – a mix of alder, loads of willow, hazel, blackthorn and wild cherry. More will follow if I manage to stop the deer eating them all.

The new apiary is in a Varroa-free region so I will not be moving my current bees there, but instead sourcing them from other areas fortunate enough to be mite-free. This is a long-term project.

The trees will need a few years to mature but the bee shed (bigger than all that have gone before 🙂 ) foundations are finished and the shed will be assembled sometime in March.

Holibobs

The holiday period is almost here. Many beekeepers will be thinking about fondant top-ups and oxalic acid mite treatment. I’ve done the latter already and – if your colonies are also broodless – hope you’ve done the same. All my hives remain reassuringly heavy but as the weather warms and brood rearing gears up I’ll have some fondant ready ‘just in case’.

I’ve covered last-minute beekeeping gifts in previous years. I think the (digital edition) American Bee Journal remains good value and provides a different perspective for UK beekeepers of what happens in the US.

And with that I’ll pour another glass of mead red wine {{8}} and wish you all Happy Christmas/Holidays (delete as appropriate).

David

{{1}}: For the East coast of Scotland … those of you living in Kent would have said it was ‘warm’.

{{2}}: I’m aware of … but it’s a tiny village.

{{3}}: Since someone accidentally burnt my laboratory down in February …

{{4}}: And I usually have no idea where they came from … so they’re initially quarantined.

{{5}}: Or have them already.

{{6}}: That’s in addition to the million and one things that normally occur during the beekeeping season.

{{7}}: And almost completely in 2019.

{{8}}: I like my bees, I’m a bit fanatical about my beekeeping, I enjoy the products of the hive … but I make pretty rubbish mead.

Join the discussion ...